The Australian Natives’ Association (ANA) lobbied strongly for the political union of Australia’s colonies at the time of Federation. It sought to shape Australia’s nationhood and identity and was a training ground for politicians.

Non-partisan and non-sectarian, the ANA was established as a friendly society for Australian-born men. By 1910 it had developed into a nationwide association with real political and social influence.

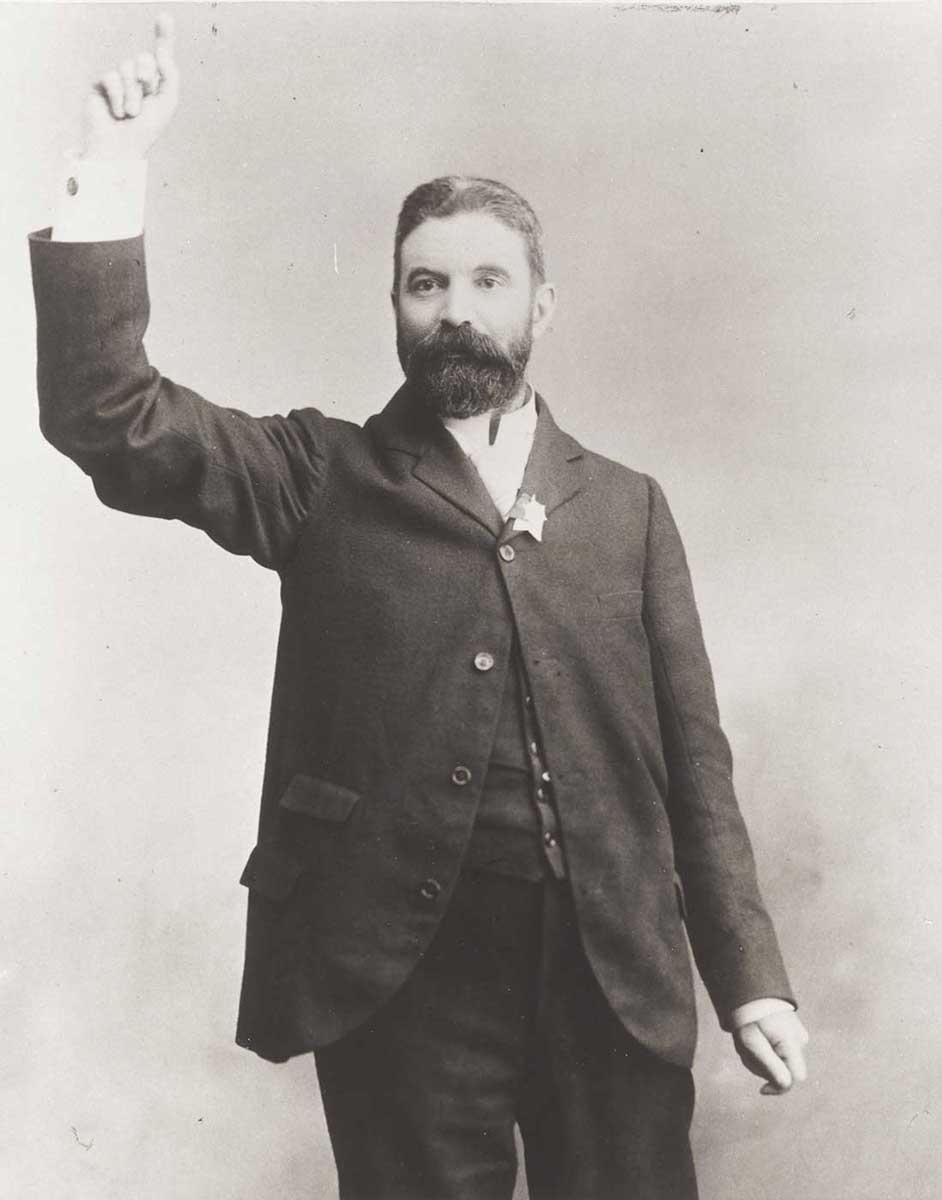

Premier of Victoria, James Service, 1887:

The Australian Natives’ Association will succeed in bringing about Federation where the politicians have failed.

Friendly societies

Friendly societies (also called benefit or fraternal societies) originated in the 18th century. They were formed by working men who paid into a mutual fund that was used to support members financially in times of sickness, distress and old age.

Friendly societies offered an early form of insurance against unemployment and illness as well as support for widows and dependent children. Many societies were also concerned with the moral, social and intellectual advancement of members.

Australian Natives’ Association

The ANA was one of many friendly societies operating in Australia in the 19th century, most of which were offshoots of British societies.

However, the ANA was an exclusively Australian organisation established in Victoria on 24 April 1871 by a group of young, white Australian-born men. It differed from many other societies in that meetings were open to all and membership did not involve rituals or regalia.

Unlike other societies, it was non-partisan and resolutely non-sectarian – banning the discussion of religious matters.

The ANA was most prominent in Victoria where it had 129 branches by the end of the 1890s. It grew rapidly into a nationwide organisation represented in all states in the early 20th century.

By 1910 membership had reached 28,844 and was broadly based across all occupations and social classes.

School for Australian leaders

From its beginning the ANA wanted to influence public thinking and policy-makers. A unifying goal was members’ determination to eliminate from Australian society any sense of cultural inferiority associated with being an Australian-born ‘colonial’ and to create a society free of British class restrictions.

Ambitious men found in the ANA opportunities to practise their oratory, develop leadership skills and to exchange ideas with many of Australia’s most influential citizens. The Association has been described as a school for politicians.

Many of Australia’s early prime ministers such as Edmund Barton, Alfred Deakin, James Scullin and Francis Forde, were members of the ANA. The first Australian-born governor-general, Isaac Isaacs, was a member, as were many premiers, members of parliament, businessmen and trade unionists.

The ANA’s relatively progressive views on women in the 1880s attracted suffragists seeking support for their cause. In 1894 the ANA advocated women’s enfranchisement.

In March 1894 a motion carried at the ANA Annual Conference stated, '... in the opinion of this conference the time has arrived when the Parliamentary franchise should be given to females over 21 years of age.'

However, for most of its existence, the ANA did not admit women as members, encouraging them instead to join a separate arm of the ANA, the Australasian Women’s Association (AWA) formed in 1900. It was not until 1964 when the two associations amalgamated that women became full members of the ANA.

Push for Federation

Federation of the Australian colonies became an ANA goal in 1884. The association’s most important legacy is the momentum it created for the Federation movement through its influential members, extensive network of branches and skilled orators such as Alfred Deakin.

The movement to colonial unification had stalled in the early 1890s because of a national economic depression, but regained momentum at the ANA-dominated federation conference in Corowa, New South Wales in 1893.

ANA branches throughout the country were mobilised to educate the public and urge support for a ‘yes’ vote at the Constitution Bill referendums in 1898 and 1899. The ANA’s mission had been to stoke nationalist sentiment for federation and leaders of the time largely credited the successful outcome to the Association’s efforts.

In 1899, Premier of South Australia Charles Kingston said, 'I warmly congratulate the Australian Natives’ Association on the prospect of the early accomplishment of Australian Union. No organisation has worked more patriotically, industriously and intelligently to bring this boon within the National grasp.'

Advancing Australia

Advance Australia was the name of the ANA’s journal between 1897 and 1919 and became the organisation’s motto in 1920.

The phrase described what the Association saw as its mission: to campaign for a socially progressive Australian society (relative to that of 19th-century Britain) by advocating for minimum wages, women’s enfranchisement and free secular education.

The ANA wanted to foster pride in being Australian by promoting the study of Australian literature and art in school, campaigning for the protection of native species, establishing 26 January as ‘Australia Day’, using Aboriginal place names and initiating a ‘Made in Australia’ movement.

Although it lobbied government to redress injury and hardship to Indigenous people resulting from government policies, the ANA was firmly of the view that Australia’s future as a socially harmonious nation lay in it being a society of white people. Support for the White Australia policy was one of the central pillars of Australian nationalism in the late 19th century.

From its beginning, the ANA was an ardent believer in a ‘White Australia’ and over the many decades of its existence its support for a restricted immigration policy did not change significantly.

Australian Unity

The ANA remained a vocal pressure group through to the 1980s, although it never again reached the heights of political influence or membership it had attained between the 1890s and 1930s.

The Association’s friendly society benefit activities assumed greater importance by the 1950s. From 1961, the ANA’s business operations included a building society, life insurance and private health insurance, aged-care facilities and dental clinics.

In 1993, the ANA merged with Manchester Unity Independent Order of Oddfellows, a British fraternal society established in Australia in 1840, to become Australian Unity Ltd.

Explore Defining Moments

References

Museums Victoria Australian Natives’ Association Collection

Robert Birrell, A Nation of Our Own, Longman Australia, Melbourne, 1995.

Judy Johnson, One Nation with One Destiny: The Role of the Australian Natives' Association in the Federation of Australia, Australian Natives' Association, Melbourne, 1984.

John Menadue, A Centenary History of the Australian Natives’ Association 1871–1971, Horticultural Press, Melbourne, 1971.

Marian Quartly, ‘Mothers and fathers and brothers and sisters: The AWA and the ANA and gendered citizenship’ in special issue Women and the State: Australian Perspectives, edited by Howe, Renate, Journal of Australian Studies, no. 37, 1993, pp. 22–30.