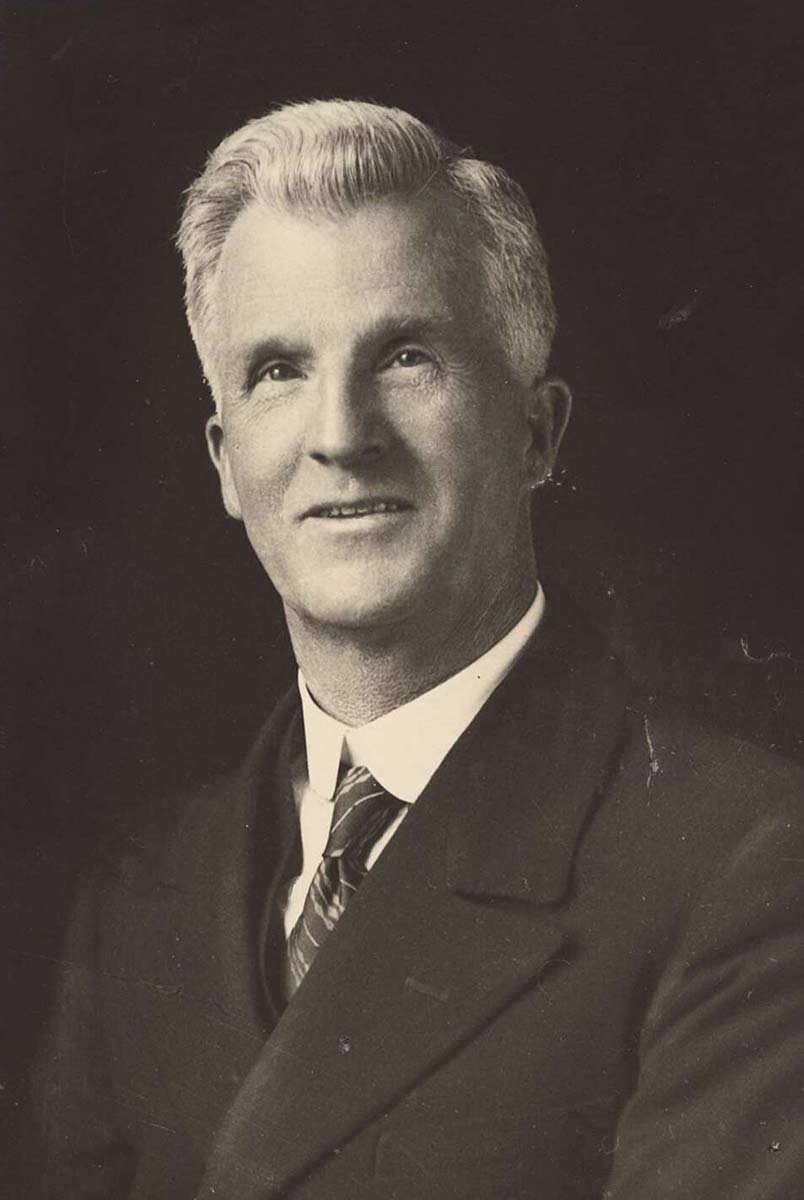

Australia’s 9th Prime Minister

22 October 1929 to 6 January 1932

Jim Scullin was the first Catholic to become Australian Prime Minister, the first Prime Minister to have come from an Irish background, and the first Labor Prime Minister born in Australia.

He became Prime Minister in 1929 at the start of the Great Depression, a devastating time for Australia and the rest of the world.

In his two years in office he was confronted by two major crises: the severe economic hardship brought on by the Depression, and the splitting of his party – Labor – into three.

Facing a hostile senate, his government was unable to pass the legislation it had prepared in order to deal with the Depression.

Scullin's beginnings

James Henry Scullin, commonly known as Jim, was born in Trawalla, Victoria, on 18 September 1876. He was the fifth of nine children by John Scullin and Ann Logan, both immigrants from Derry, Ireland. His father, John, had been a miner and later a plate-layer on the railways.

James Scullin attended small state schools, first at Trawalla and later at Mount Rowan near Ballarat. He left school at 14 or so to work in a grocery store, but continued his education through night classes and wide reading in the Ballarat public library.

Scullin learnt debating skills as a member of the Catholic Young Men’s Society and the Australian Natives’ Association. He won prizes for debating at Ballarat’s South Street competitions, which he later also judged for 30 years.

He worked at various manual jobs, including wood-chopping, mining and farming. In his mid-twenties he began to run a grocer’s shop in Ballarat, a job which he kept for the next ten years.

In 1903 Scullin joined the Political Labor Council (PLC), a forerunner of the Australian Labor Party (ALP). As part-time political organiser for the Australian Workers’ Union from 1906 he helped found PLC branches across western Victoria.

He stood unsuccessfully against the Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin, as the Labor candidate for the seat of Ballarat at the federal election in December 1906, and married Sarah McNamara in 1907.

Scullin's entry into federal politics

Scullin won the federal seat of Corangamite for Labor at the general election on 13 April 1910. He soon proved to be a capable parliamentary debater. After losing his seat at the general election on 24 June 1913, he became editor of the Labor daily newspaper, the Ballarat Evening Echo, a position he held until re-entering parliament in 1922.

Scullin was a leading opponent of conscription in the years 1916–1917, and at the ALP’s interstate conference on the issue in December 1916 he moved a motion to confirm the expulsion of those supporting conscription. The ALP split over this issue in November 1916.

He contested the Corangamite seat again at a by-election on 14 December 1918. Under the new preferential system of voting, he topped the poll on the first count. However, after preferences were distributed, he lost to the Farmers’ Union (later renamed the Country Party) candidate, WG Gibson, who became the first Country Party member elected to federal parliament.

In 1918–1919 he was president of the ALP’s Victorian branch; at the Victorian state election on 21 October 1920 he stood unsuccessfully for the seat of Grenville; and at the 1921 ALP interstate conference he was a prominent advocate of the socialisation objective adopted by the party.

Scullin re-entered federal parliament as the ALP candidate for the seat of Yarra at a by-election on 18 February 1922, held following the death of the previous member, Frank Tudor, the ALP’s Leader of the Opposition. He retained the seat for almost 28 years, through ten general elections.

On 26 April 1928 Scullin was elected federal parliamentary ALP leader, succeeding Matthew Charlton (who resigned because of ill health) at a time of discord between the party’s moderate and radical factions.

Despite ALP disunity and a long-running violent strike by waterside workers, the ALP under Scullin’s leadership won eight seats from the Stanley Melbourne Bruce–Earle Christmas Page Nationalist–Country Party coalition at the general election on 17 November 1928.

Prime Minister James Scullin

Scullin led the ALP to victory at the general election on 12 October 1929, following the fall of the Bruce-Page coalition on 10 September. The ALP, out of office for 13 years since the 1916 split over conscription, won a huge 29-seat House of Representatives majority but failed to wrest control of the Senate from the coalition.

As well as the prime ministership, Scullin took the External Affairs and Industry portfolios, in which he served October 1929–January 1932.

Inability to control the Senate proved a major obstacle to Scullin’s government in combating the Great Depression. The Depression began when the Wall Street stock market crashed in New York on 29 October 1929, a week after Scullin formally took office (on 22 October).

The crash brought about a worldwide economic depression in the early 1930s, resulting in bank failures, collapse of investment, mounting unemployment, falling commodity prices and slackening of trade.

When his Treasurer and Deputy Prime Minister, EG Theodore, stood down in July 1930 after being implicated for defrauding the government in the Mungana mines affair, Scullin also took on the role of Treasurer.

During a seven-month period in this role, Scullin presented his government’s first budget to parliament on 9 July 1930. Scullin’s budget planned for increased expenditure to be met through increased income tax and postal charges and the introduction of a sales tax.

The Melbourne Agreement

As a result of the government’s difficulty in meeting interest payments on overseas debts, Scullin agreed to invite to Australia a Bank of England delegation led by Sir Otto Niemeyer. Niemeyer formed a poor impression of Scullin’s grasp of economic issues.

Scullin, however, was well read in conventional economics and had been horrified by the state of the economy he had taken over – with its high level of debt, falling export commodity prices and rising unemployment.

The Bank of England delegation met with Scullin and state premiers at a special premiers’ conference in Melbourne during August 1930. On Niemeyer’s advice, the conference agreed to a heavily deflationary package of measures (known as the Melbourne Agreement) for tackling the Depression.

This involved balancing budgets, ceasing overseas borrowing until all external debts were paid, confining internal borrowing to income producing schemes, reducing government expenditure (including spending on social services) and cutting wages.

Scullin spent four and a half months, from August 1930 to January 1931, overseas attending the Imperial Conference (of heads of government of dominions of the British Empire) in London.

While there he secured the appointment of Isaac Isaacs, Chief Justice of the High Court, as Governor-General, which was against the wishes of King George V. Scullin firmly resisted the King’s view that a member of the UK nobility should be appointed.

He also succeeded in persuading the UK Government to reduce interest payments made by the Commonwealth government by £1.6 million annually, and to drop plans for reducing Imperial preference tariffs on Australian wine, dried fruits and sugar.

Disunity in Labor

During Scullin’s months in the UK, the ALP caucus was deeply divided over the implementation of the Melbourne Agreement.

The Acting Prime Minister, JE Fenton, and Acting Treasurer, JA Lyons, supported by the absent Scullin, adhered to the agreement. Opposing them were ‘inflationists’ (the group supporting Theodore’s views) and ‘Langites’ (the group supporting the New South Wales Premier’s position).

Three weeks after returning from the UK, Scullin persuaded the ALP caucus to reinstate Theodore as Treasurer. This action affronted Fenton and Lyons, who resigned from cabinet. Soon after, they joined the All For Australia League, and went on to help found the United Australia Party.

At a second Special Premiers’ Conference in February 1931, Scullin and JT Lang were in conflict over the Depression policy. Scullin favoured Theodore’s proposals for credit expansion financed via the Commonwealth Bank. Lang wanted a repudiation of interest payments overseas and interest on government borrowings in Australia cut to three per cent.

The next month, when EJ Ward, a Lang protégé, entered parliament following a by-election on 7 March, Scullin barred him from caucus on the grounds that he did not represent the ALP.

Five Langites quit the ALP and, with Ward, formed the Lang Labor group, which held the balance of power. The ALP had therefore split three ways – between the Lyons defectors, the Lang supporters and those who remained loyal to Scullin.

The Premiers’ Plan

Scullin’s difficulties – with Robert Gibson of the Commonwealth Bank and with the Senate – reached crisis point during March-April 1931. Gibson refused Scullin further credit until he cut pensions, which he refused to do.

As Treasurer, Theodore introduced a Bill to enable the government to issue ‘fiduciary notes’ to fund its social welfare policies. However, the parliament would not pass the Bill.

The impasse led Scullin to call a special three-week Premiers’ Conference in May-June 1931, resulting in the Premiers’ Plan, which became the strategy for combating the Depression used by both the ALP and subsequent United Australia Party governments.

The Premiers’ Plan was adopted by the government and the Opposition in June 1931, though half the parliamentary ALP voted against it.

The plan provided for five basic strategies: (1) reduction of 20 per cent in all adjustable government expenditure (including government salaries and pensions); (2) 22.5 per cent reduction of interest on internal government debt (that is, Australian-held bonds); (3) increased federal and state taxation; (4) reduction in bank interest rates; and (5) relief for holders of private mortgages. It was a restructuring of public finances on the ‘equality of sacrifice’ principle.

The plan signified the dominant influence over financial policy now exercised by the academic economists on whose advice governments were increasingly relying.

Scullin’s government was brought down in the House of Representatives on 25 November 1931. The immediate issue was the Lang Labor group’s allegation that Theodore had distributed unemployment relief corruptly.

When Scullin refused Lang Labor’s demand for an inquiry, it joined the Opposition, now led by Lyons, in passing a ‘no confidence’ motion against the government. Parliament was dissolved and a general election was called for 19 December 1931.

Scullin's later political life

Scullin campaigned well at the 1931 election, effectively using the new medium of radio, but the election was a disaster for the ALP and for him personally, with the first United Australia Party forming government under the leadership of JA Lyons.

The ALP was reduced to 14 seats, and seven former ALP ministers, including Theodore, lost their seats. Scullin now became Leader of the Opposition, but was weakened by the small parliamentary representation of the ALP and continuing conflict with Lang.

The ALP won an additional four seats at the general election on 15 September 1934, but Scullin was bitterly disappointed at the result. In poor health, he resigned the ALP leadership on 1 October 1935 and was replaced by John Curtin.

Retiring to the backbench, Scullin chose a low profile. He became an advocate for banking reform, and for the control of banking and credit by parliament. After the ALP’s return to power on 7 October 1941, Scullin served an important informal mentor role for both Curtin and his successor, JB Chifley.

In failing health, he retired in December 1949 at the close of the 18th parliament.

Scullin died on 28 January 1953 and was buried in the Melbourne General Cemetery, after a state funeral and requiem mass in St Patrick’s Cathedral conducted by Archbishop Daniel Mannix. His supporters in the Labor movement later erected a tall, granite Celtic cross above the grave.

Legislation passed under Scullin

In its legislative program the Scullin government was severely impeded by an overwhelming opposition majority in the Senate. A great many of the bills passed were in support of measures more favoured by the Opposition than by the government, particularly those bills which were aimed at dealing with the economic crisis. Major legislation included:

- The Gold Bounty Acts 1930 and 1931 were part of measures to help solve balance of payment problems.

- The Financial Emergency Acts (No. 1 and No. 2) 1931 reduced social welfare benefits and Commonwealth salaries in line with the ‘Premiers’ Plan’ agreement.

The Scullin government’s legislation program was more noteworthy for bills which failed to pass, including:

- The Central Reserve Bank Bill 1930, introduced by EG Theodore, was initially supported by former Treasurer ECG Page and by many private bankers but was blocked in the Senate for ‘political’ reasons.

- Constitutional referendum bills defeated in 1930 aimed to provide for direct power to the Commonwealth to legislate on all industrial matters, on all trade and commerce issues and to allow Parliament to amend the constitution by an absolute majority in both Houses.

In our collection