On 12 November 1894 Lawrence Hargrave, Australian inventor, astronomer, explorer and historian, connected four box kites of his own design.

Having added a seat, he flew with the kites 16 feet (4.8 metres) off the ground, thus proving to the world that it was possible to build a safe, heavier-than-air flying machine.

Octave Chanute, American aviation pioneer:

If there be one man more than another who deserves to succeed in flying, that man is Mister Lawrence Hargrave of Sydney.

Hargrave’s youth

Hargrave was born in 1850 in Greenwich, England. His father moved to New South Wales in 1857, and in 1865 his family joined him. The elder Hargrave was a foundation judge in the District Court and eventually secured a position on the Supreme Court.

Only months after arriving in Sydney, Lawrence joined the ship Ellesmere as assistant to the expedition leader Abraham Thompson in an exploratory circumnavigation of the continent.

Unfortunately, the months at sea took Hargrave away from his studies and he failed his matriculation examination. Unable to follow his father into the law he was apprenticed to the Australasian Steam Navigation Company, where he learned many of the practical engineering skills that served him well throughout his life.

Exploration and cartography

The journey on the Ellesmere left a positive impression on Hargrave and between 1872 and 1877 he worked as engineer on six different expeditions.

However, his career as an explorer was not without tragedy. He joined the brig Maria in 1872 headed for New Guinea in search of gold under the leadership of Reverend Dr John Dunmore Lang.

The ship sank after striking Bramble Reef off the coast of North Queensland with the loss of 35 of the 75 passengers and crew on board.

This disaster failed to discourage Hargrave and three years later he joined the politician, amateur scientist and patron of the arts Sir William Macleay’s research voyage to New Guinea as engineer on board the Chevert.

He left this expedition after six months to join another voyage, this time with the Ellengowan, again as engineer.

Hargrave returned to Sydney in January 1876 but by April had signed on with another expedition led by the Italian explorer Luigi d’Albertis. Hargrave and d’Albertis had a grave falling out over the Italian’s looting of sacred objects from local villages and Hargrave resigned his position.

In 1877 Hargrave, now a respected explorer and cartographer, was back in the Torres Strait investigating the viability of pearl farms on behalf of a British firm. This was to be his last expedition to Australia’s north.

Astronomy

In October 1878 Hargrave took a position at the Sydney Observatory. Over the next five years he observed the transit of Mercury and was involved in an attempt to observe the transit of Venus (that failed due to poor weather).

He also observed conditions related to the 1883 eruption of the Indonesian volcano, Krakatoa – the greatest volcanic eruption in recorded history.

While at the observatory, Hargrave designed and built adding machines to assist in his astronomical calculations.

Early Australian inventions

By 1883, due to his father’s wise investments in land, the younger Hargrave enjoyed an independent income of about £1,000 a year. He was now able to commit himself fully to scientific research.

From 1882 Hargrave had been intrigued by the motion of animals:

It will be evident that a remarkable analogy exists between walking, swimming and flying. It will appear further that the movements of the tail of the fish and the wing of the insect … can be readily imitated and reproduced. These facts ought to inspire the pioneer of an aerial navigation with confidence.

He began experimenting with monoplanes, focusing on wing shape, and from 1887 worked on an engine-powered aircraft powerful enough to carry a human.

In 1889, after experimenting with 36 different designs, he developed a three-cylinder rotary engine that became a prototype for the aircraft engines that dominated the first 50 years of powered flight.

Box kites

In the 1890s the poor power-to-weight ratio of most engines and inefficient propeller design meant that aeronautical pioneers focused more on the study of gliding and wing design rather than powered flight.

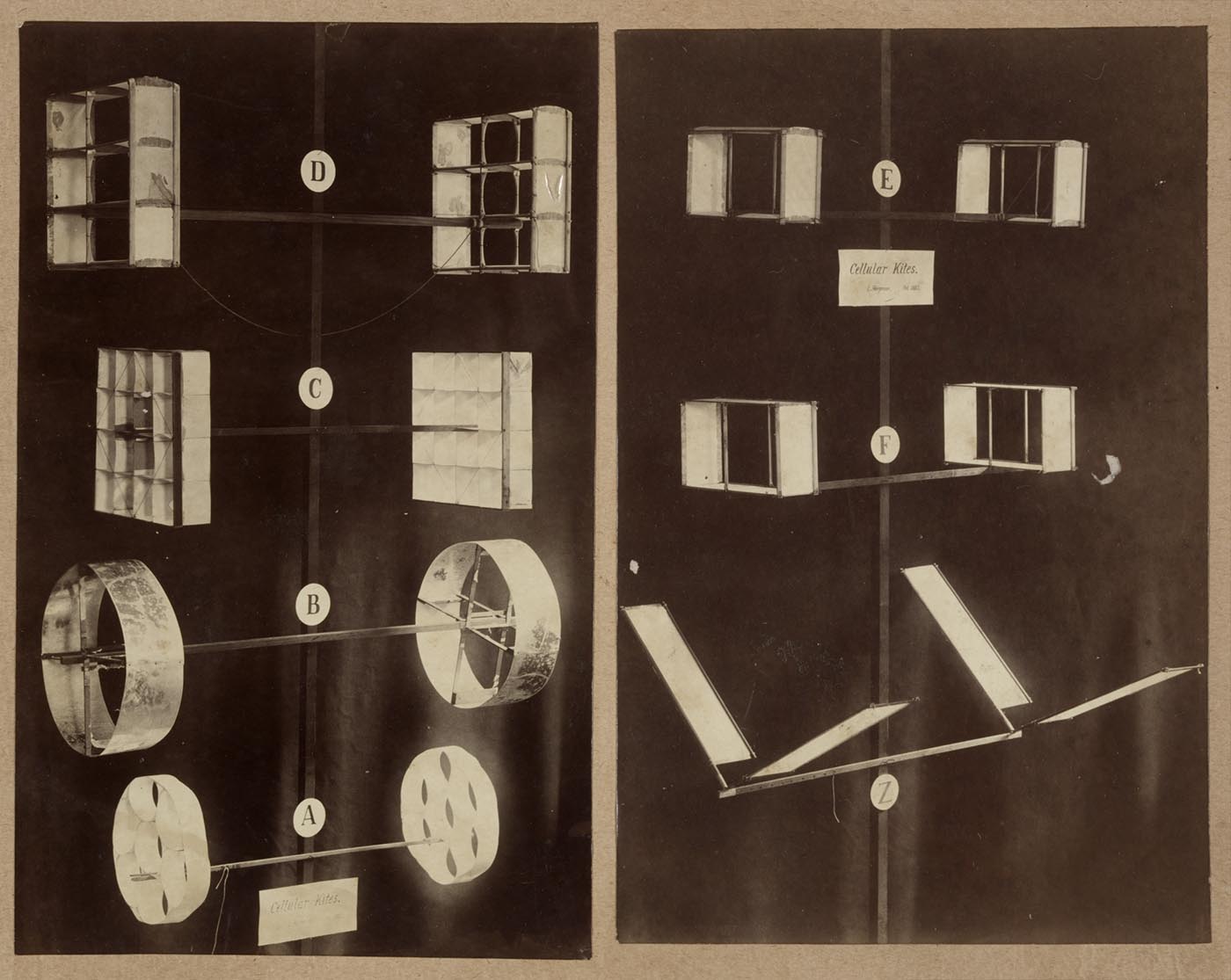

Hargrave produced a series of monoplane gliders, but unhappy with their stability began to study box kites instead:

I am using kites, and find perfect stability can be got by making them of three dimensions instead of two … cellular kites do not confine their surface to one plane, but distribute it in various portions, forming cells through which the wind blows.

Stanwell Park

In 1878 Hargrave married Margaret Johnston with whom he had six children. In 1893 the family moved to Stanwell Park between Sydney and Wollongong where they owned property and coal mines.

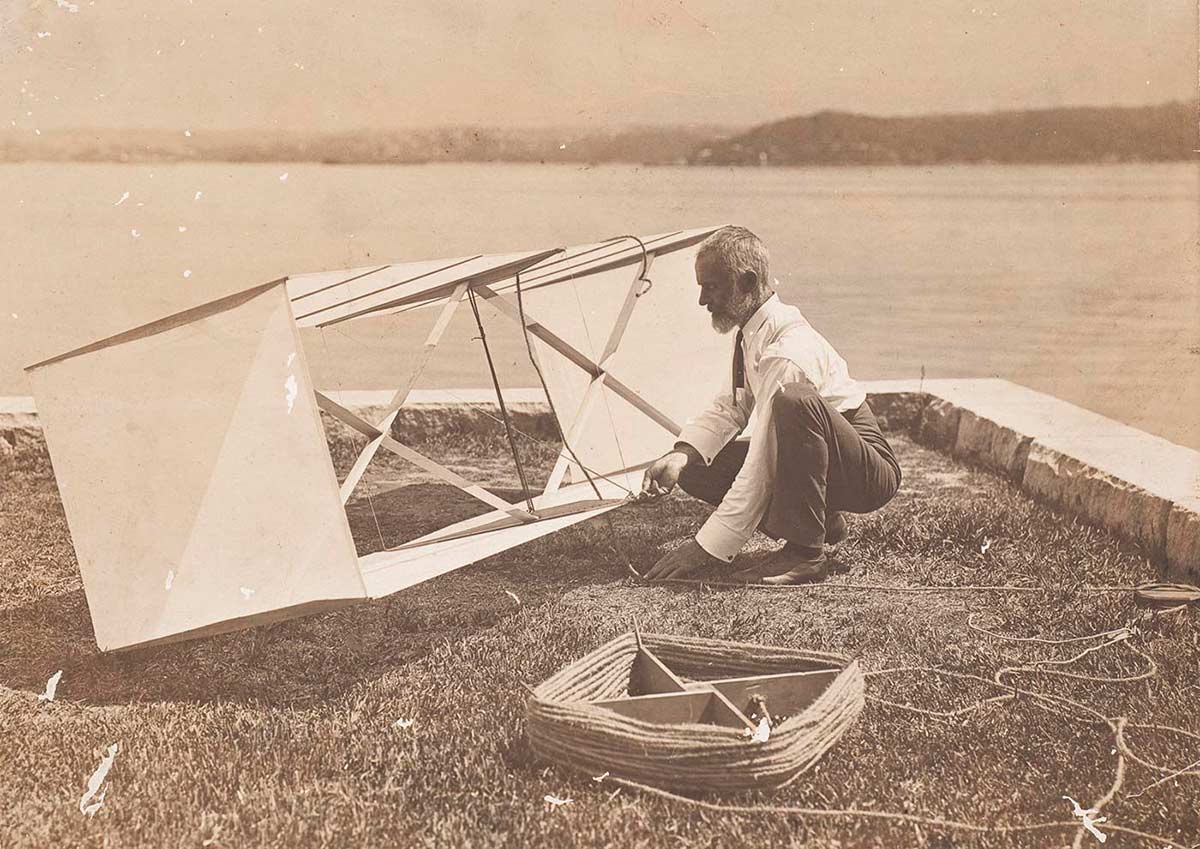

The area is well known for its favourable gliding winds and on the morning of 12 November 1894 Hargrave launched a linked series of four box kites off the town beach and then climbed into a seat attached to the lowest kite. A strong gust propelled him into the air, but because of their box design the kites remained steady in the buffeting winds.

Having proven that human flight on a stable, multi-winged craft was possible, he said, ‘The particular steps gained are the demonstration that an extremely simple apparatus can be made, carried about, and flown by one man … without any risk of accident.'

Hargrave’s designs were quickly taken up by other inventors, including the American Octave Chanute, who he was in correspondence with, and whose designs were later incorporated by the Wright brothers into their Wright Flyer, the first aircraft to achieve powered flight with a pilot on board in December 1903.

Hargrave's later life

Hargrave’s interest in aeronautical experimentation continued throughout his life. His later research included investigations into ways the curvature of wings could increase lift. His designs strongly influenced early human flight and he is recognised today as one of the great pioneers of aeronautics.

Hargrave’s only son Geoffrey was killed in action in May 1915 during the Gallipoli campaign and only weeks later Hargrave himself died of complications from surgery in Sydney on 6 July 1915, aged 65.

References

W Hudson Shaw and Olaf Ruhen, Lawrence Hargrave: Aviation Pioneer, Inventor and Explorer, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 1988.

JD Walker, Lawrence Hargrave: Australia’s Pioneer Aeronautical Scientist, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1984.