In 1954 Dr David Warren first came up with the idea of a device that would record not only flight data but also voices and other sounds in aircraft cockpits immediately prior to a crash.

The prototype he designed in the late 1950s met with indifference in Australia but was greeted with enthusiasm elsewhere in the world.

Today flight recorders are mandatory on all major aircraft throughout the world and have made a huge contribution to air safety.

Warren to senior staff at the Aeronautical Research Laboratories, 1954:

In investigating … accidents … anything which provides a record of flight conditions, pilot reactions etc for the few moments preceding the crash is of inestimable value.

Black box flight recorders

Using ‘black box’ flight recorders, air crash investigators can download hours of cockpit conversation as well as large quantities of flight data recorded immediately prior to the crash. This helps them determine the cause of a crash and contributes to preventing similar ones.

The pilots’ conversations with each other, with air traffic control and with other planes are all valuable data because 80 per cent of crashes involve a human factor.

It was a series of crashes in the early years of commercial jet aircraft travel that initiated the idea of creating an extremely reliable recording device that could withstand massive trauma and deep saltwater immersion.

De Havilland Comets

In 1949 the British aviation firm De Havilland launched the Comet – the world’s first jet airliner. The fast and comfortable plane caught the imagination of the public. However, from 1952 to 1954 seven Comets crashed, resulting in the deaths of 110 people.

Several of the aircraft disintegrated at high altitude, with no survivors, witnesses or immediate clues as to what had happened.

In 1954 the entire fleet of Comets was permanently grounded, and the most comprehensive air crash investigation ever undertaken began. It eventually found the crashes were caused by metal fatigue, due in part to the aircraft’s square windows.

Meanwhile, in Australia the Department of Civil Aviation had held a meeting of experts to discuss the possible cause of the crashes. One of these experts was 28-year-old Dr David Warren, a chemist specialising in aviation fuels at the federal government’s Aeronautical Research Laboratories (ARL) in Melbourne.

Lightbulb moment

During the inconclusive meeting, it struck Warren that the problem with discussing the Comet crashes was that there was simply too little data. Often the people best placed to have known what might have caused the crashes were the flight crew who were all dead.

At the same time, he remembered seeing a device at a trade fair a few weeks before. This was a German-designed dictaphone that recorded sound on steel wire.

At that time, flight data recorders were used in some military test aircraft, but were not used in commercial planes or for crash investigation purposes. Voice recorders were not used at all.

Soon afterwards, Warren wrote a memo to his manager suggesting that ARL develop a voice recorder, pointing out that it is often essential to know what the pilots were experiencing at the time of the crash and why they made the decisions they did.

This could be recorded along with flight data in a crashproof container. He also made the point that as aircraft continued to fly faster, higher and further, crashes would become more common, and the need to understand why they occurred correspondingly more urgent.

Prototype development

Warren’s superiors expressed only limited interest and told him to pass the project to ARL’s instruments section. However, because the latter was overstretched, the flight recorder project languished, and Warren resorted to working on a prototype in his garage on weekends.

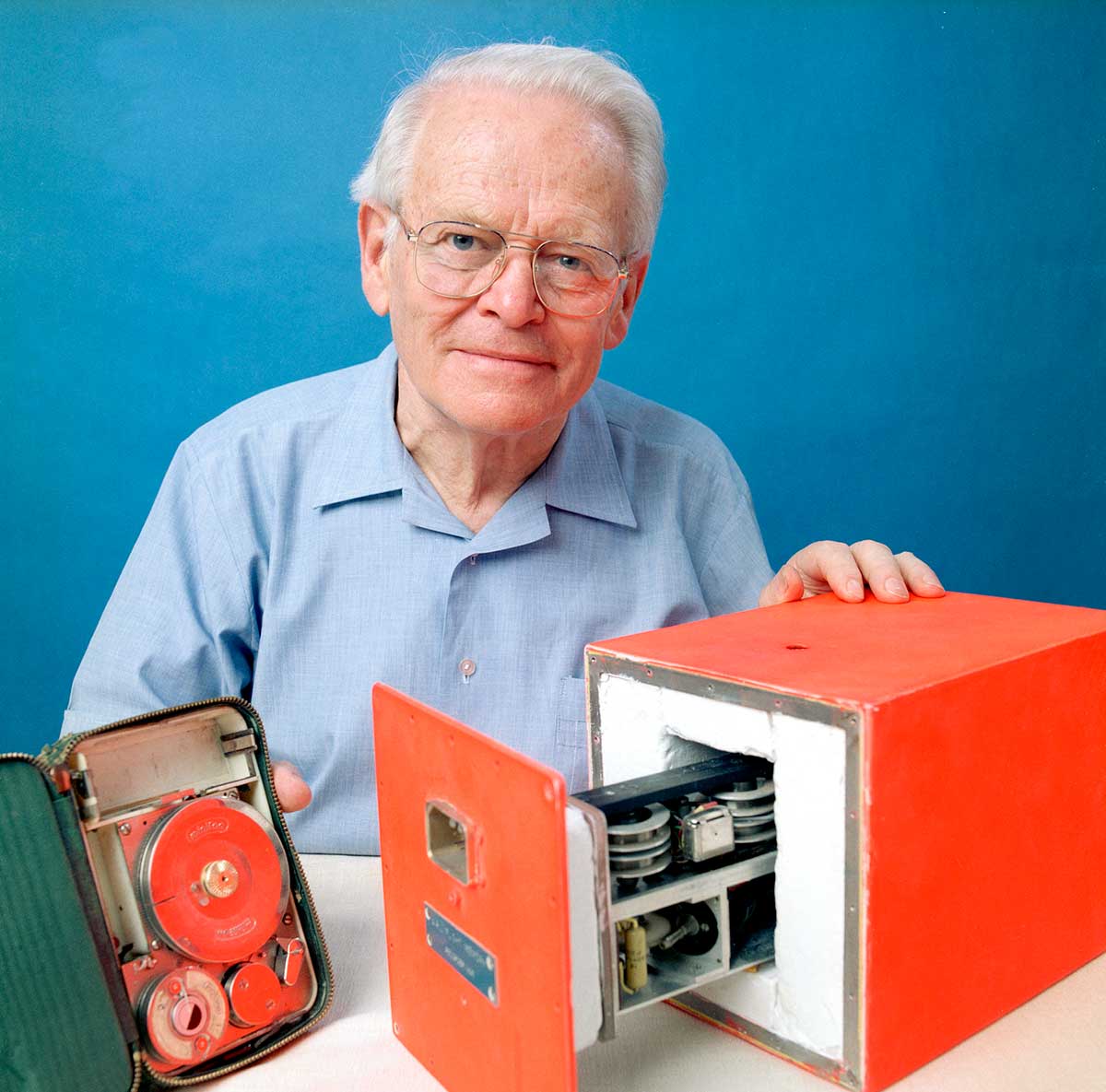

By 1957 Warren had a new, more supportive manager in Tom Keeble, who encouraged him to write a detailed paper for distribution among aviation authorities in Australia. Keeble also found £600 to pay for a professionally-built prototype.

The device recorded four hours of cockpit sound, and recorded eight instrument readings four times a second, on the same durable steel wire. It required little maintenance, turned on and off automatically with the aircraft’s engines and was self-erasing (unless there was a crash).

Warren’s paper advocated that flight recorders be installed in all major aircraft and addressed possible concerns about weight, size, cost, pilot privacy and maintenance. However, it met with a lack of interest, even hostility, in Australia. Keeble and Warren then sent it to relevant organisations overseas, but failed to receive any meaningful response.

The local indifference was partly a result of there being relatively few air crashes in Australia, and a perception that Britain and the United States were the centres of aeronautical innovation, not Australia. (And yet, in 1967 Australia would become the first country to make the installation of both data and voice recorders mandatory in major aircraft.)

Mandatory installation

In early 1958 Sir Robert Hardingham, Secretary of the British Air Registration Board, visited the ARL. During the tour, the ARL’s chief superintendent, Lawrence Coombes, introduced Hardingham to Warren, who showed him the flight recorder.

Despite the earlier distribution of Warren’s report among British aviation bodies, it seems that Hardingham was unaware of the device. He was impressed with the recorder and invited Warren to bring the device to the United Kingdom.

Warren spent a month there and his flight recorder was greeted with enthusiasm by the various aviation authorities to whom he demonstrated it.

It began a movement to make flight recordings mandatory on all British civilian aircraft. On his way back to Australia, Warren visited similar organisations in the United States, but was met with little or no interest.

On his return, the ARL gave Warren its full support. He was given a team – Lane Sear, Ken Fraser and Walter Boswell from the instruments section – to develop a pre-production standard prototype, which was completed in 1962.

The device’s recordings were now greatly improved, and increased to 24 readings a second. Also incorporated were a fire-resistant and shockproof case and a ground-based decoding device.

However, the ARL did not apply for patents until many of the design elements were already in the public domain. This allowed firms elsewhere in the world, particularly in the United States, to develop the idea, thereby capturing a growing market as the installation of flight recorders became mandatory around the world.

Legacy

The Australian Government eventually received £1,000 for ARL’s intellectual property, but it has otherwise made no profits from the invention of a device that is installed in thousands of aircraft every year.

David Warren died in 2010. Eight years earlier, he had been appointed an Officer of the Order of Australia for his services to aviation.

References

Biography of Dave Warren, Defence Science Technology

Black box flight recorders fact sheet, Australian Transport Safety Bureau

Black Box … to Black Hawk: Sixty Years of Aeronautical Achievements, Aeronautical and Maritime Research Laboratory, Melbourne, 1999.

Janice Peterson Witham, Black Box: David Warren and the Creation of the Cockpit Voice Recorder, Lothian Books, South Melbourne, Vic., 2005.