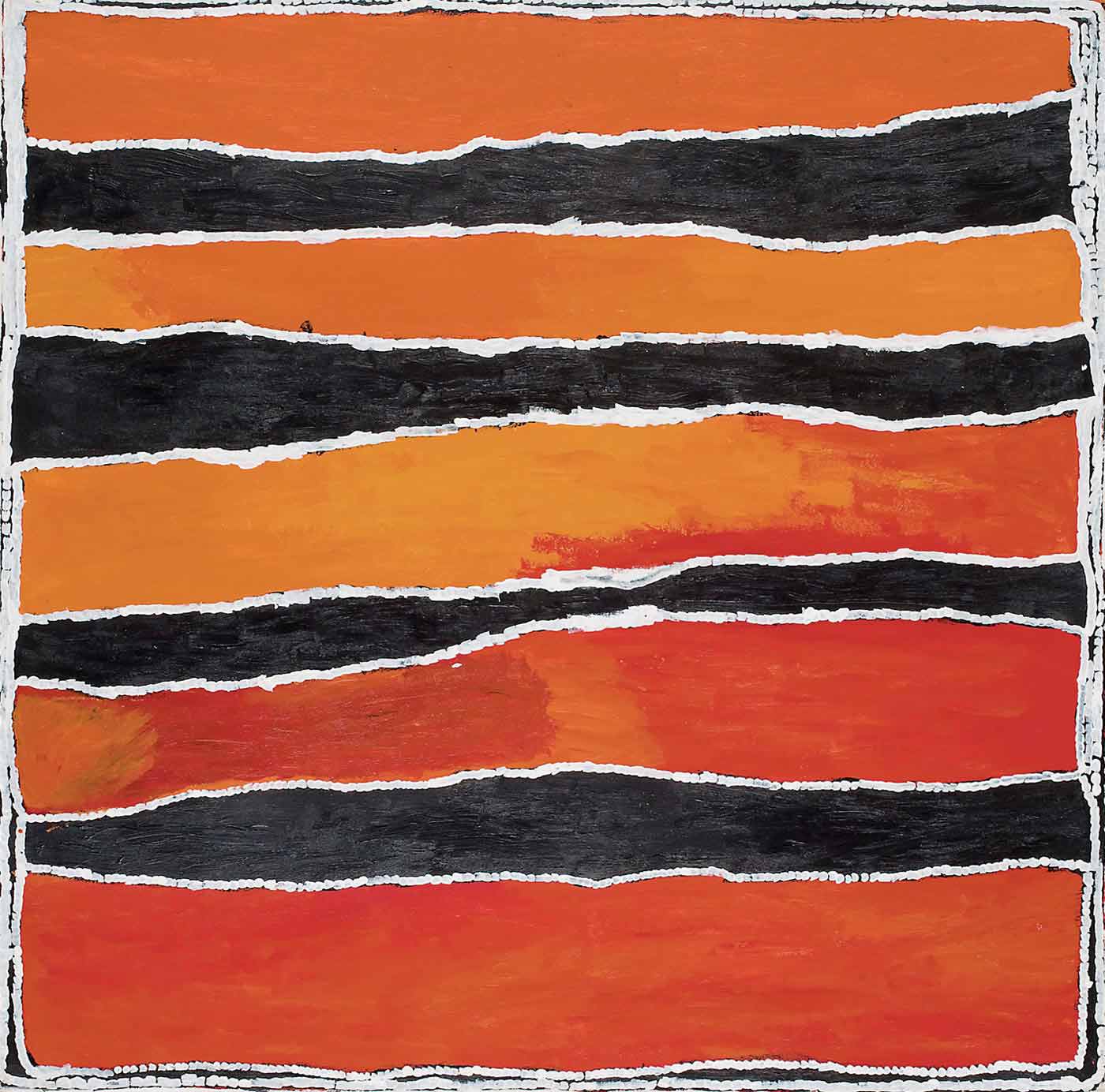

Jukuja Dolly Snell, Fitzroy Crossing, 2007:

When you go there you have to light a fire, so that jila can know you’re coming.

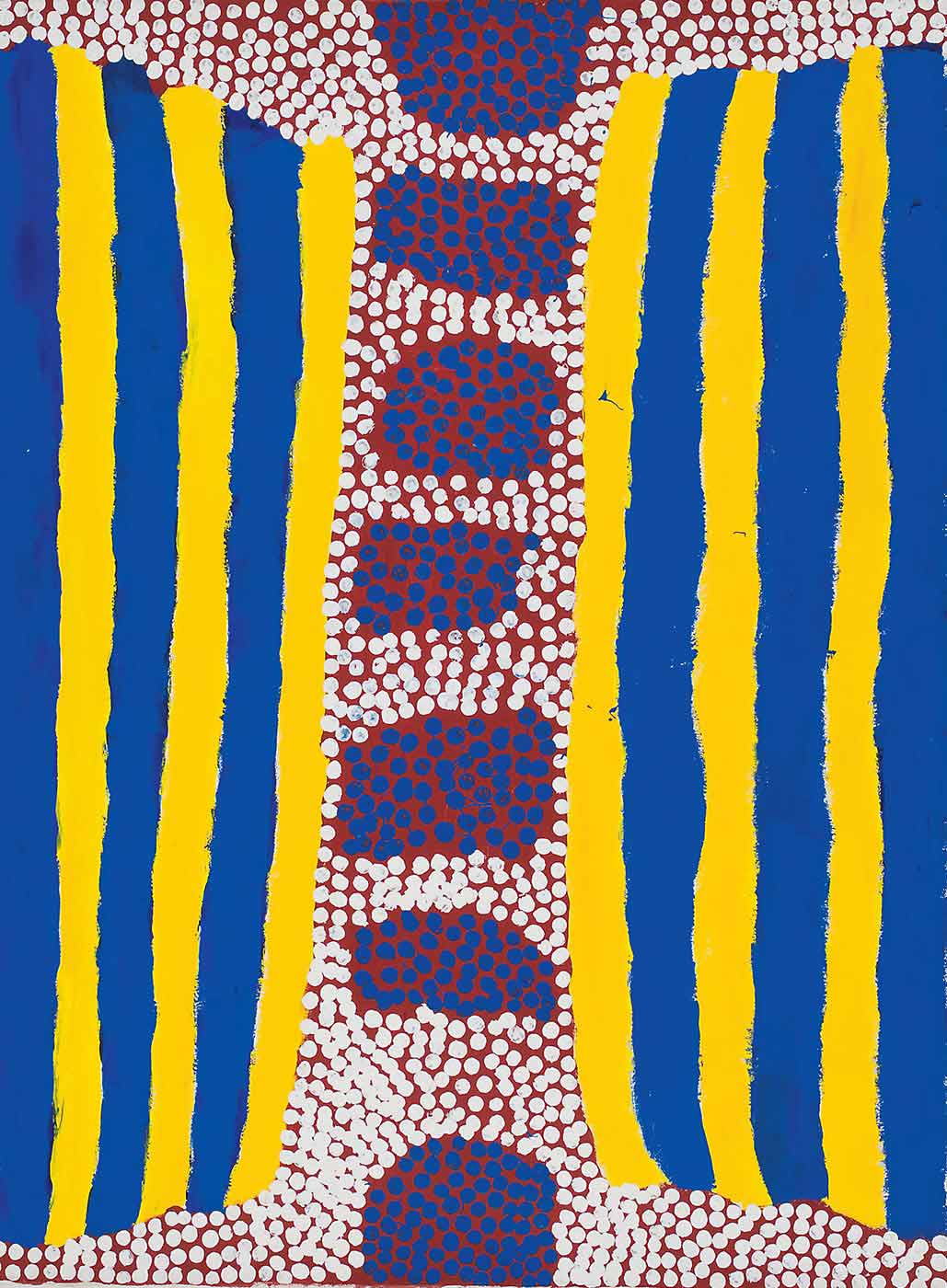

Of the 200 permanent springs in the jila Country, only about 30 are inhabited by the powerful ancestral beings known as jila or kalpurtu (rainbow serpents). Two of these springs, Kulyayi (Well 42) and Kaningarra (Well 48), became stock route wells.

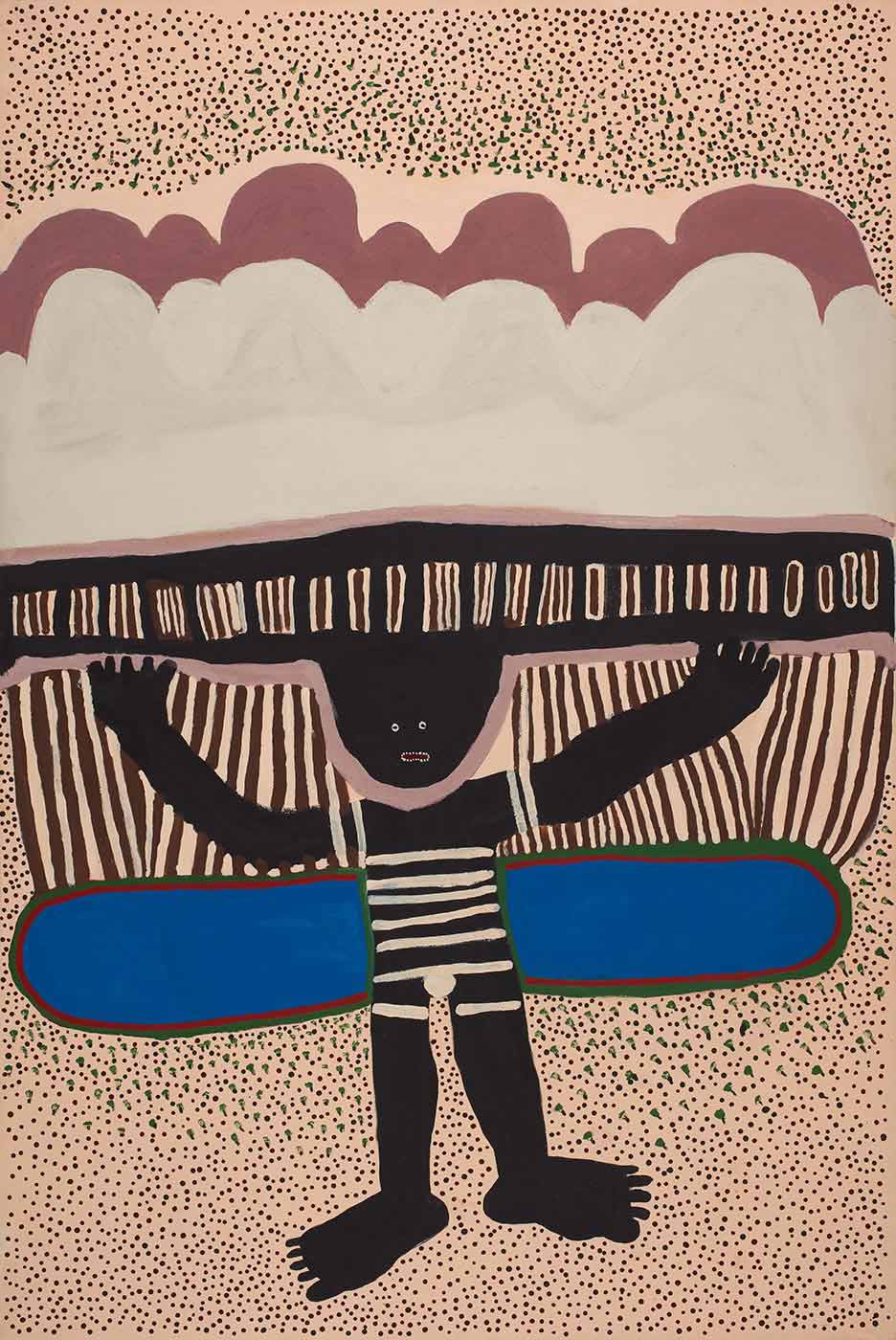

Before they became snakes, however, these ancestral beings were men who made rain, shaped the features of the land and introduced practices of law into the jila Country. Many of the jila men were also companions who travelled the desert visiting one another, and creating the ceremonies and singing the songs still performed here today. One by one, the jila men ended their journeys at the springs that bear their names; as they entered them, they transformed into kalpurtu.

These are sites of profound importance to Aboriginal people, and are approached with great respect.

Jukuja Dolly Snell, Fitzroy Crossing, 2007:

When you go there you have to light a fire, so that jila can know you're coming.

Jila, such as Kaningarra, Kurtal and Wirnpa, are formidable places, and can be dangerous if not approached properly. Aboriginal people enter Wirnpa, which lies west of the stock route, ritually, sweeping the ground with branches and approaching in single file.

Wirnpa was one of the most powerful of the jila men and the last to travel the desert before becoming a snake and entering the spring, which bears his name. His adventures are celebrated in the songs and stories of many language groups.

Today, many of these people worry about proposals to mine the Country around Wirnpa.

Jawarta Donald Moko, Bidyadanga, 2007:

Wirnpa the proper boss. Rich. Too many money. Kartiya can't get that. We got snake, jila. Can't touch.

These contemporary concerns are echoed in the history of the Canning Stock Route, where the sinking of the wells over jila had some catastrophic results.

Milkujung Jewess James, Ngumpan, 2007:

They were looking for water at Kulyayi. They dug down and found that snake. Kartiya shot it. They killed him, poor thing.

At Kulyayi, which became Well 42, history and the Jukurrpa collided. During the excavation of the well the great rainbow serpent Kulyayi was killed, either by Alfred Canning's original party or his reconditioning team.

Some accounts say Kulyayi was killed by explosives, while others suggest he rose up in anger and was shot dead. Recent accounts also stress the intimate and ecological impact of the cultural clash.

Lloyd Kwilla, Wangkatjungka, 2009:

It's like an icon, like Sydney Harbour Bridge. If someone came and bombed that, blew it away, people would be devastated, empty. That place would be changed. Well, people felt empty when he [Kulyayi] was gone. They felt something not there anymore, they can't come back. They moved away. Animals moved away. People, animals, they're connected. Something valuable was lost, you can't replace it.

The white men who built or rebuilt the Canning Stock Route wells had no knowledge of beings such as Kulyayi, or of the complex desert world they inhabited. Kulyayi's death reveals the profound impact the Canning Stock Route wells had on the life of the jila Country.

Not all jila faced Kulyayi's fate. Either side of the stock route, jila such as Kurtal and Wirnpa live on at these sites. Their enduring power and importance is asserted in the songs, ceremonies and paintings of their people.

Explore more on Yiwarra Kuju