Ngumarnu Norma Giles, Warburton, 2008:

This is wonderful. We’re back here in our own Country, our traditional Country.

Throughout the 20th century, social, cross-cultural and ecological pressures have pulled Aboriginal people from their homelands and pushed them into the settlements that fringed the desert.

People were drawn to the Canning Stock Route by the lure of beef, flour, sugar and tobacco, although conflict and fear sometimes drove them away. While some families followed the drovers and found new lives at the stations and missions, others kept their distance.

Droughts in the desert in the mid-20th century made life very difficult in some areas. At such times the stock route missions and stations were seen as reliable sources of food and water, and so became increasingly attractive.

Some people gravitated towards these settlements out of necessity, others out of curiosity about the changes occurring at the edges of their desert world.

For others, it was loneliness that brought them in from the desert. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the few remaining groups came in; often they had come looking for their walyja, their families. One of the last major migrations of Martu people occurred in 1963, when several of the artists featured in this exhibition decided to move to Jigalong.

The movement of people away from the stock route Country had a huge impact on desert society. Having settled on distant missions and stations, people were separated not only from their Country but also from their extended families.

But the desert people never stopped thinking about their Country. With the recognition of land rights and native title in the 1980s, people started to return to Country to set up their own communities. Places such as Mulan, Kunawarritji, Parnngurr and Patjarr were created out of the will of people to live in their own Country again.

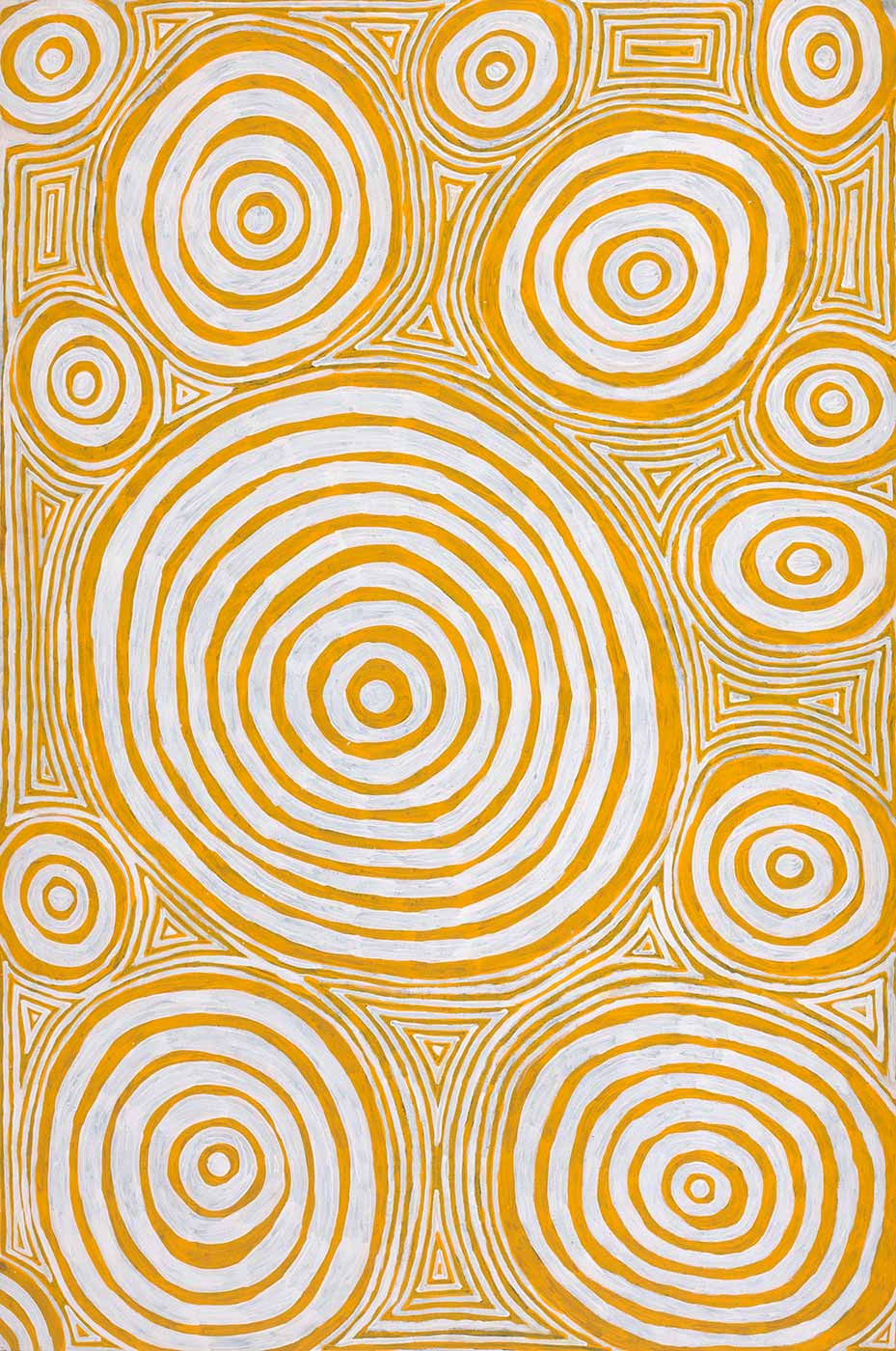

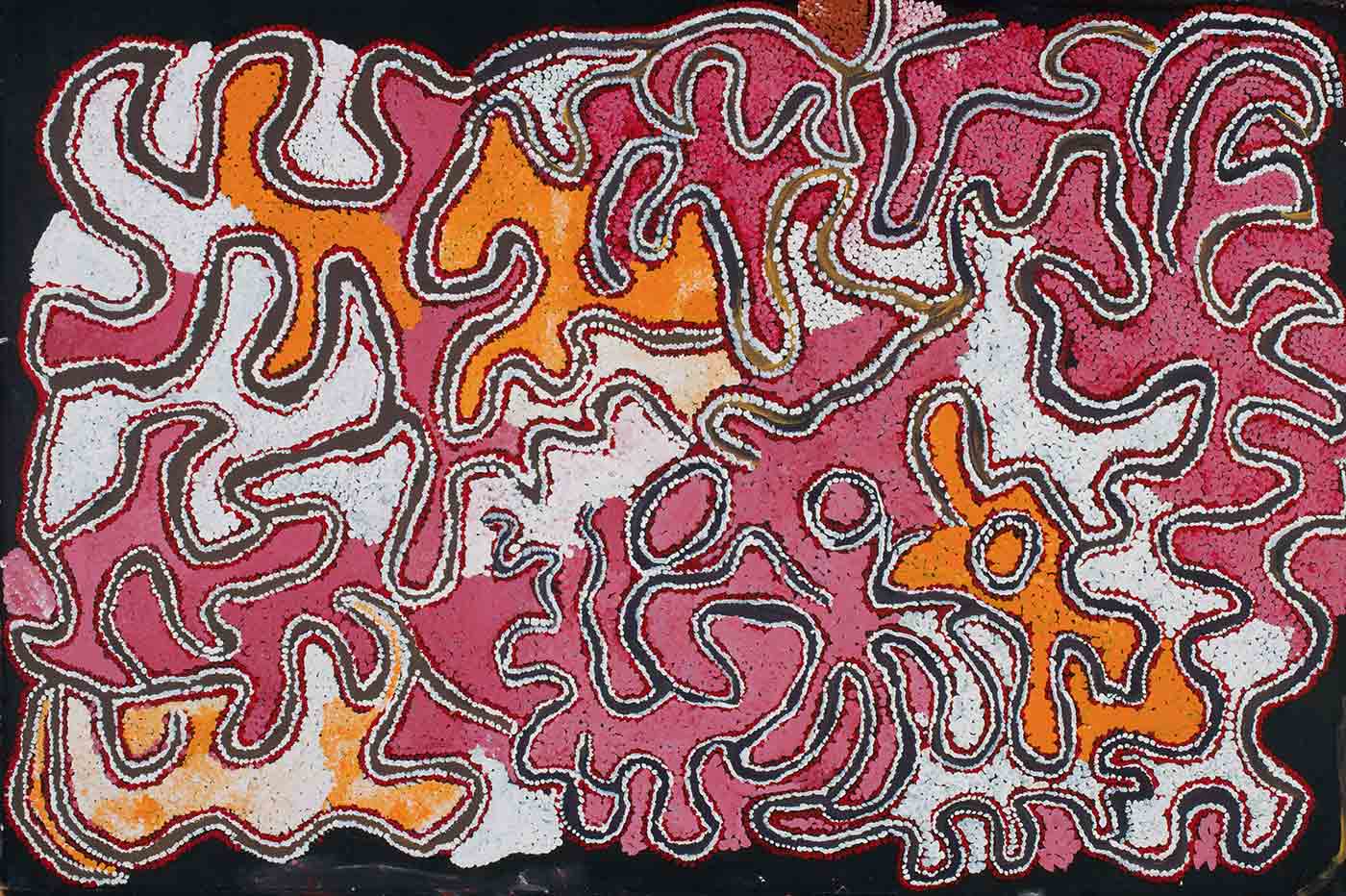

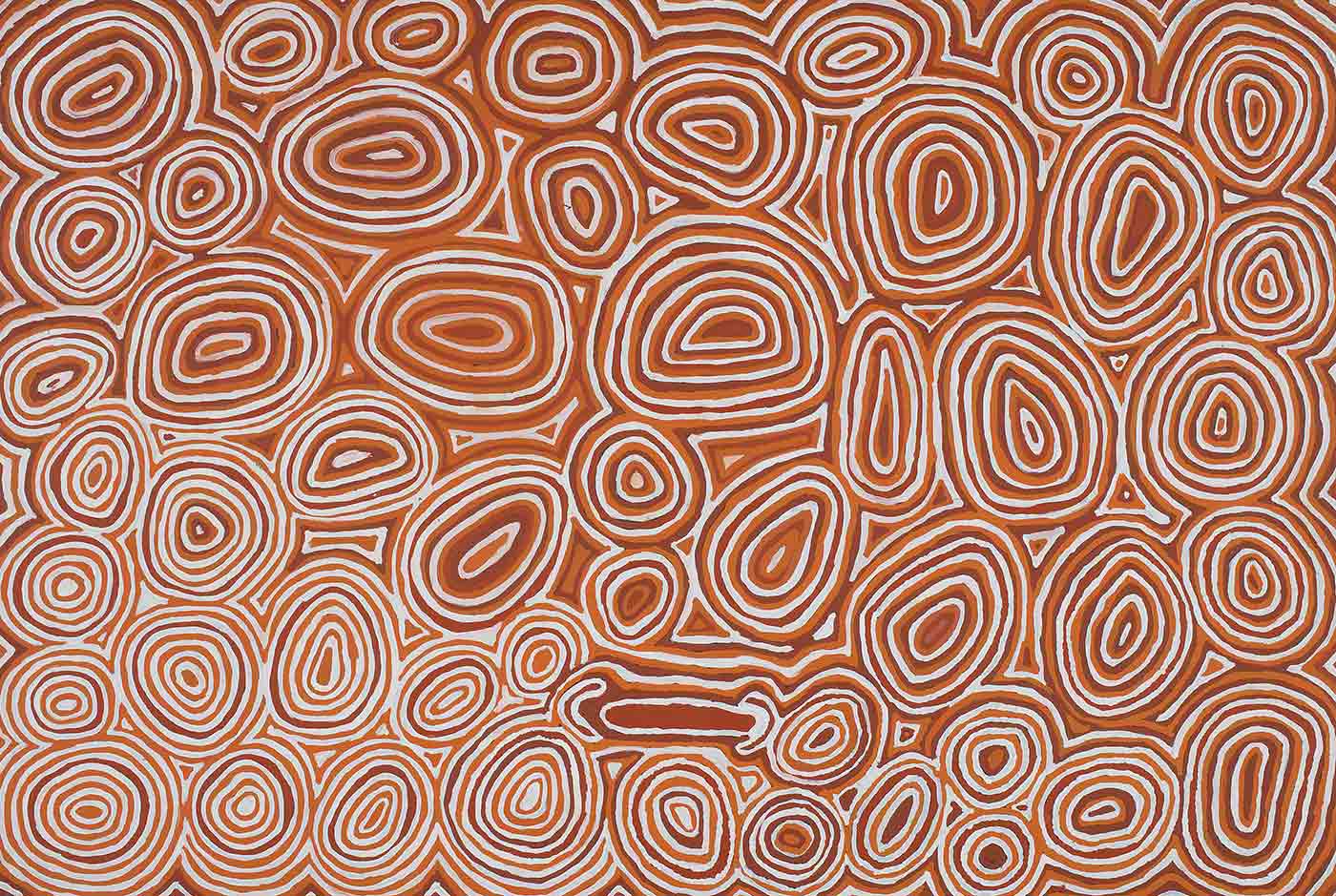

In these remote places there is little access to the mainstream economy, and art has become an integral part of the cultural and economic lives of the Aboriginal people who live there. The relationship between art and Country remains vital.

This section explores the artists from one community, Patjarr, and the relation between their art, their Country and their community life.

Kayili Artists

Ngumarnu Norma Giles, Warburton, 2008:

We decided to set up an art centre to be based at Karilwara [Patjarr], our family’s traditional home. We were the ones who started this and we want it to be strong always. Strong art centre — strong community. Future generations will still be here painting.

Kayili artists live at Patjarr, seemingly a long way from the Canning Stock Route. But like their families further north and west, these artists spent the first part of their lives in their Country around the Gibson and southern Great Sandy deserts. They have particularly strong family connections to Papunya Tula Artists at Kiwirrkurra, Martumili Artists at Parnngurr and Jigalong, and Birriliburu Artists in Wiluna.

While many of these families initially walked east to Jigalong mission or north to Balgo, Kayili artists such as Jackie Giles and Pulpurru Davies walked south to Warburton mission. It was from there that they would later set out to found their own community – and art centre – at Patjarr.

Explore more on Yiwarra Kuju