Waruwiya [soak] and Pilalyi rock hole. I lived around here with my mother and father. Nyirla is our Country. I was walking around everywhere in that Country, that was the last time. [Then] we travelled to them waterholes on the Canning Stock Road, until we came closer to Natawalu. That’s where we saw a helicopter for the first time.

The people of the Western Desert moved across their land in a rhythm determined by the seasons and by their social and ceremonial duties.

The coming of the drovers, however, introduced different kinds of movement and different reasons to move. The drovers brought with them intriguing new things from the world beyond the desert: beef, tea, flour, sugar, tobacco, new medicines.

The desert people sometimes followed the drovers and helped them in return for such goods. In the end, many followed the stock route out of the desert and onto cattle stations, such as Billiluna, or missions, like Balgo and Jigalong. But not all families took this path. And not everyone walked out of the desert, as is shown by the story of ‘Helicopter’ Tjungurrayi.

In 1957 a mining survey party came across a group of people living near Natawalu (Well 40). Some of these people had never seen white men before. None had seen a helicopter.

Ten-year-old Tjungurrayi was seriously ill, so the survey team flew him and his mother’s sister, who was also ill, north to Balgo for medical attention. When they failed to return, their worried family members began travelling north in groups.

Charlie Wallabi (Walapayi) Tjungurrayi, 2007:

My young brother [Helicopter] was so sick; he had sores everywhere and he was helpless, a little boy. I grabbed my little brother and showed them. So kartiya looked at his sores and said, ‘OK, we’ll take him,’ because he was so sick. So I asked the kartiya, ‘Are you going to bring him back?’ He was speaking his language and I was speaking my language. I kept on saying, ‘Are you going to bring him back?’

I waited, waited, waited for long and I wondered, ‘They’re not bringing him back!’ Nothing. It was getting a bit longer, and I said to myself, I think I’ll go after him north. From there I kept walking right, long way, all the way to Balgo.

The initial contact between the helicopter crew and the local families was marked by fear and confusion on both sides. Patrick Olodoodi (Alatuti) Tjungurrayi remembers those first cross-cultural exchanges:

It landed. We said, ′Manurrkunurrku [wasp] sat down’. We didn’t call it helicopter then. We called it manurrkunurrku. ‘Well, let’s go look for it,’ we said. That’s when we came down from the sandhill carrying spears.

James Ferguson, the helicopter pilot, found himself confronted with a group of Aboriginal men dragging their spears between their toes: ‘Matman grabbed the .303 and I pulled out my revolver but all was OK. They stuck their spears in the ground’. Patrick recalls that it was his brother, Charlie Wallabi (Walapayi) Tjungurrayi, who intervened:

‘Put them spears down,’ he told us. We put them down and started walking towards him.

Despite the initial tension, relations between the crew and the family group warmed as they interacted and shared food. These encounters are remembered with fond humour today:

We asked Brandy [Tjungurrayi] to go and ask them if we can get kapi [water] from the well. He went and told that kartiya, [in Kukatja] ’Are you listening to me? Kapi!′

‘Kopi? Ahh, you want coffee,’ [the whitefella] said. He filled up a billycan with coffee and gave it to him. Then he brought it over to us. I had a look and saw that it was black. ‘What the hell is this black water?’ I said. It smelt different too.

All of the artists featured in this section were witness to, or had relatives who were present during, the events at Natawalu.

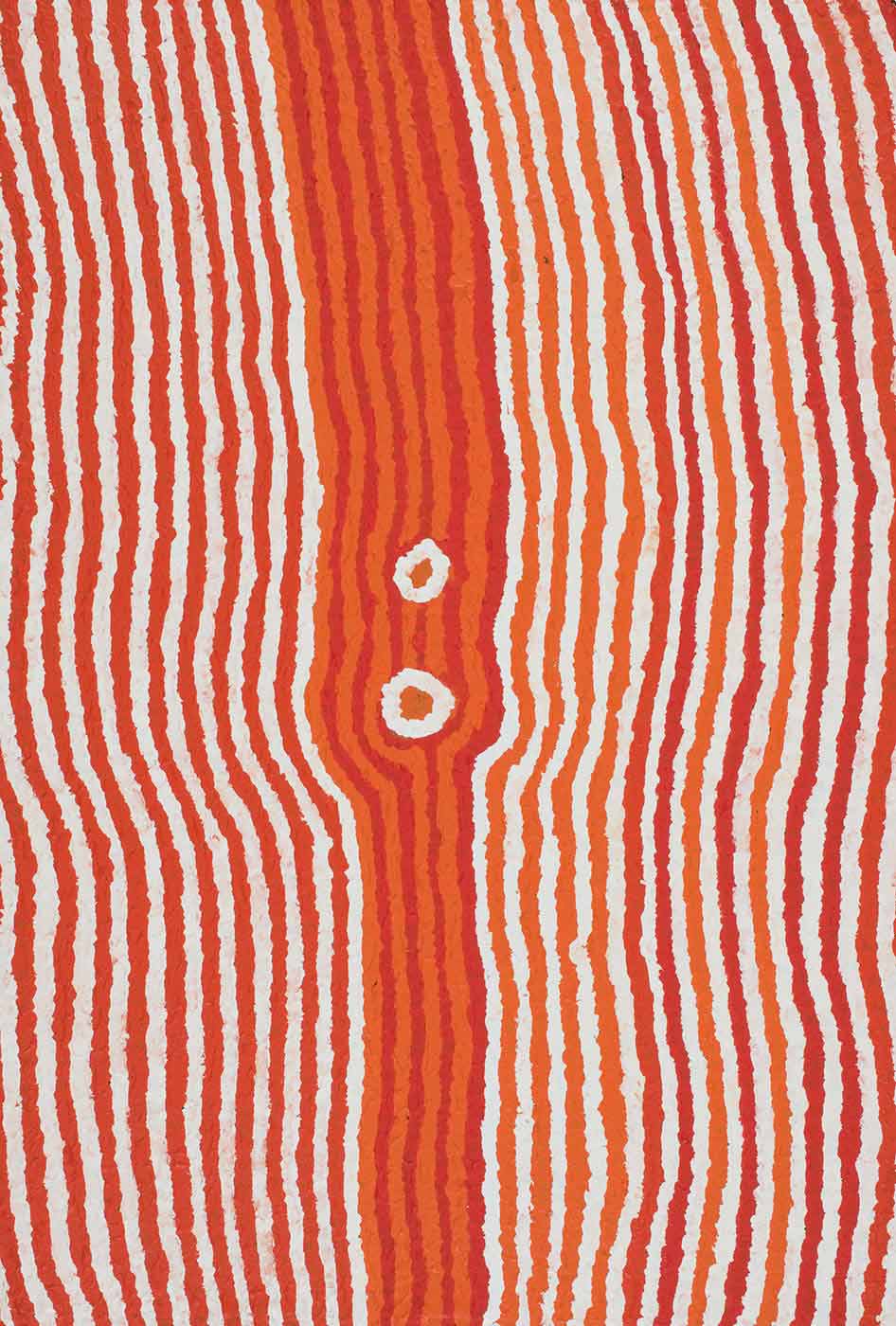

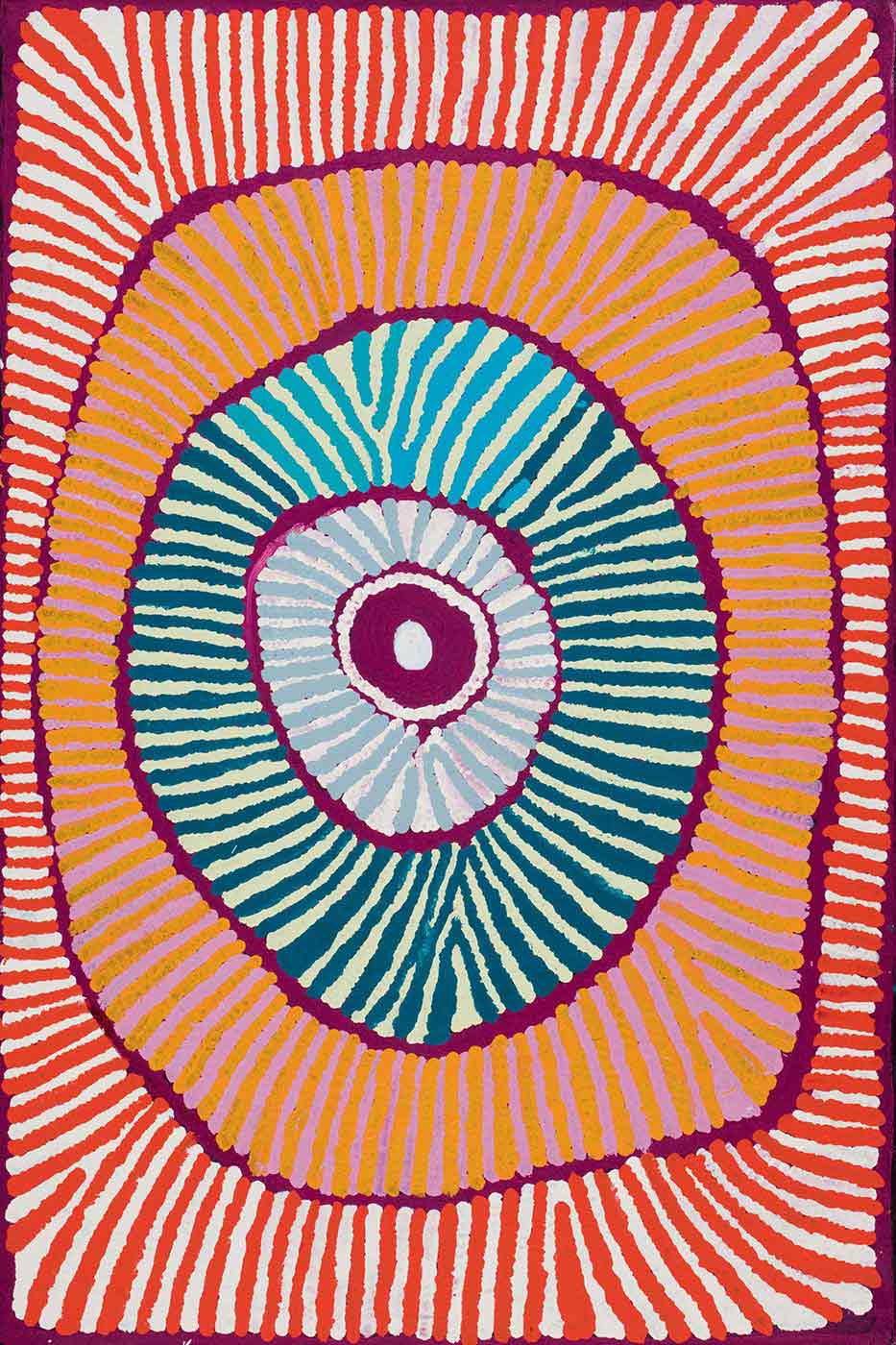

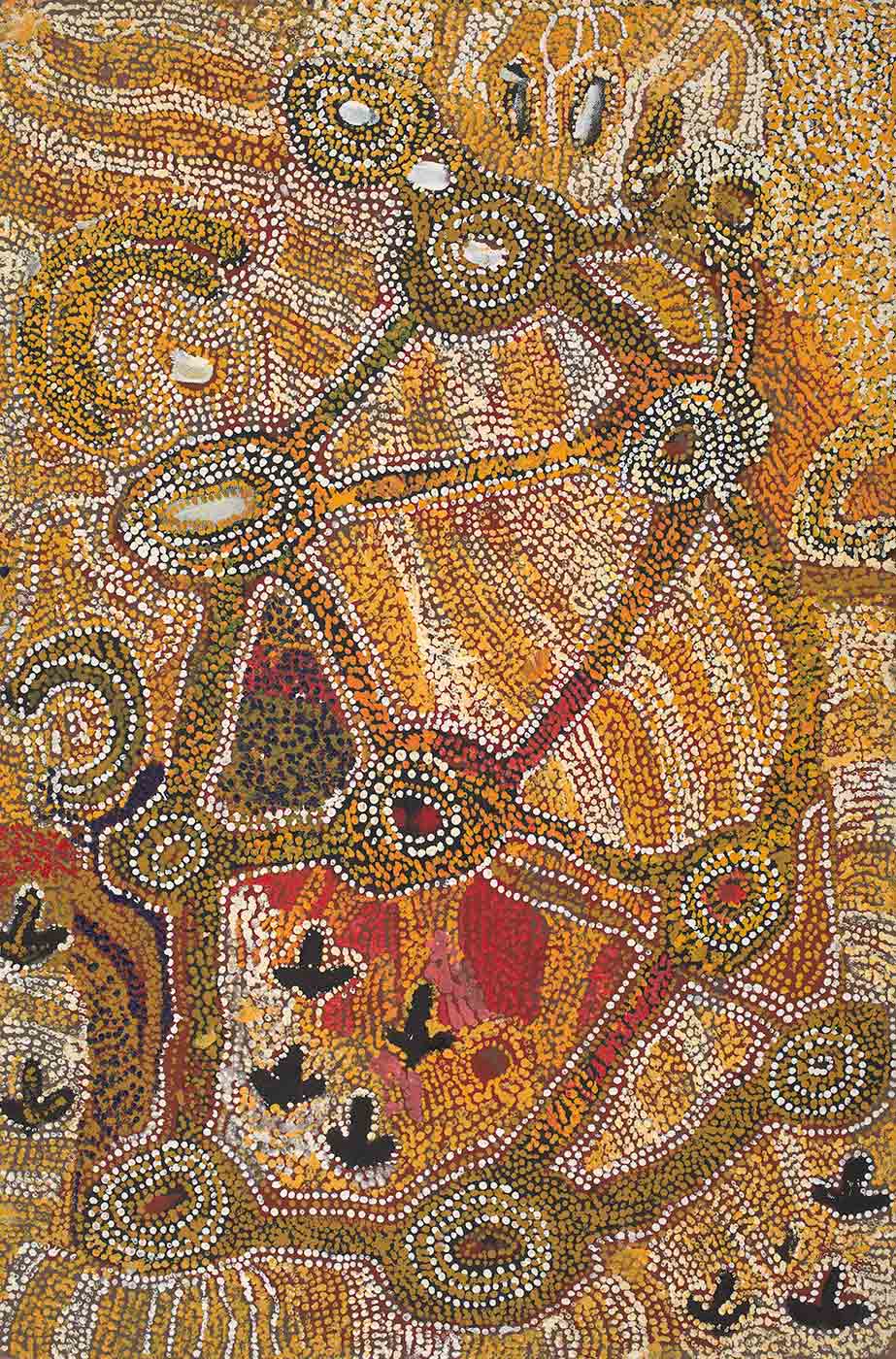

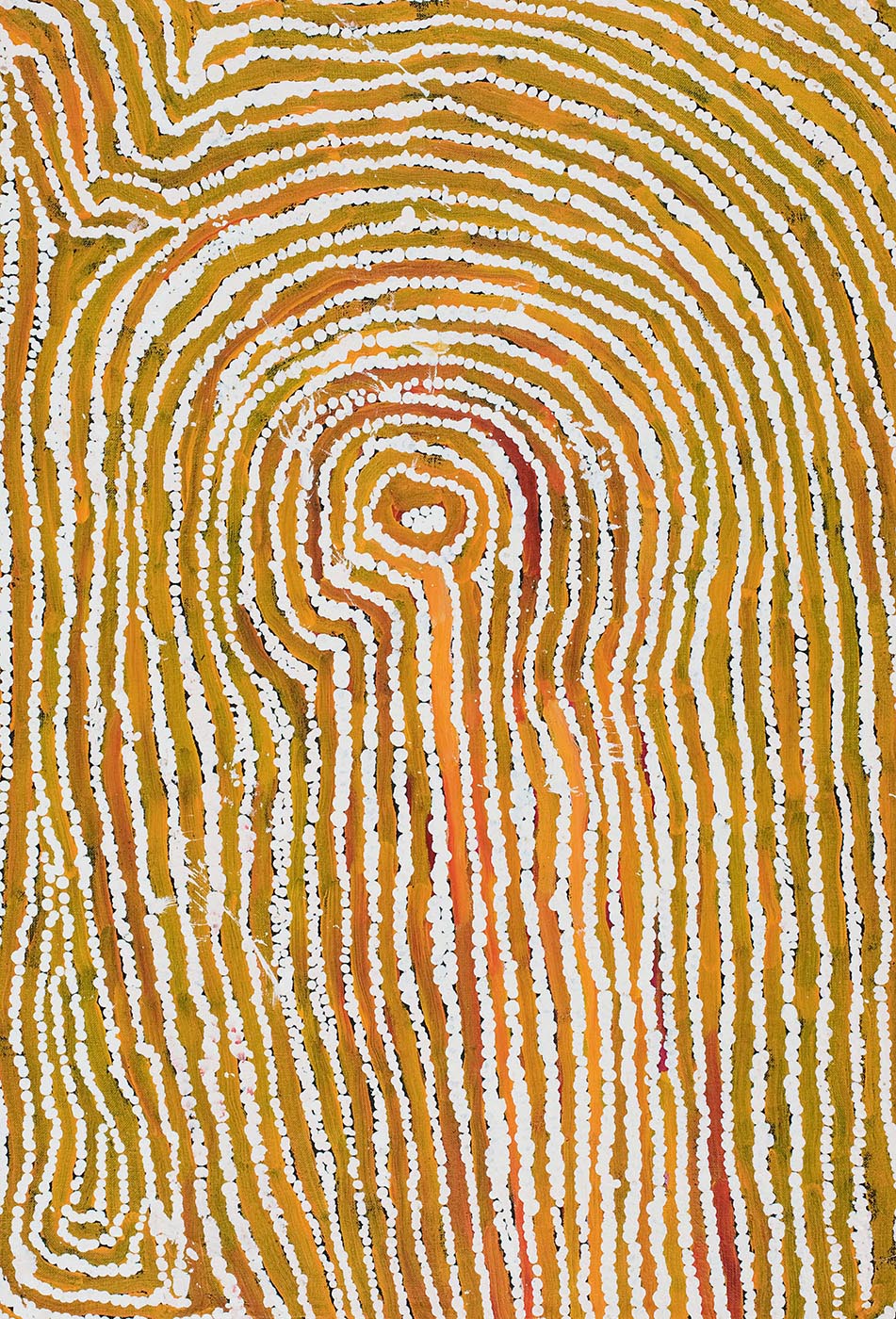

Waruwiya by Helicopter Tjungurrayi

Natawalu by Helicopter Tjungurrayi

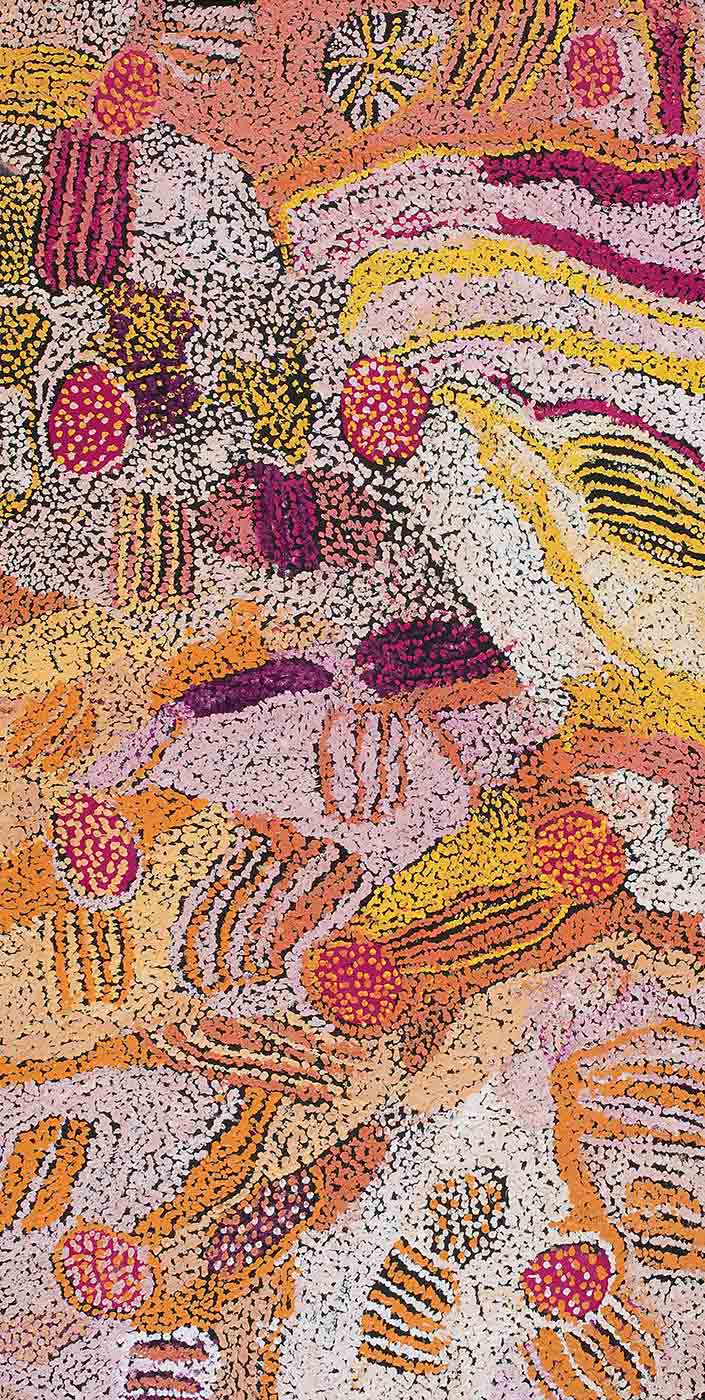

Winpurpula by Christine Yukenbarri

Mangarri (Food) by Elizabeth Nyumi

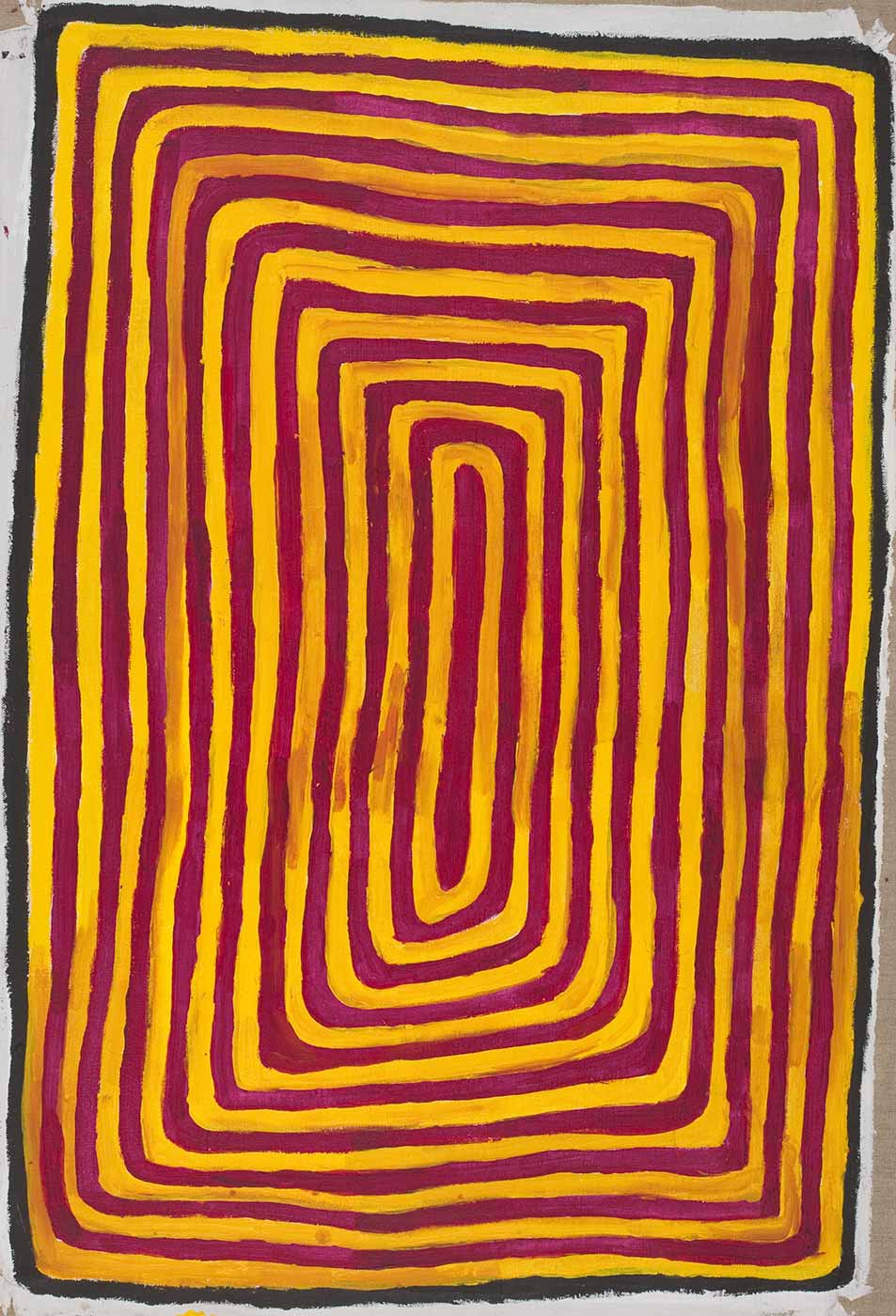

Nyaru by Charlie Wallabi Tjungurrayi

Nyaru by Brandy Tjungurrayi

Untilted by Josephine Nangala

Untitled by Miriam Napanangka

Nyakungtjuungku by Lucy Loomoo

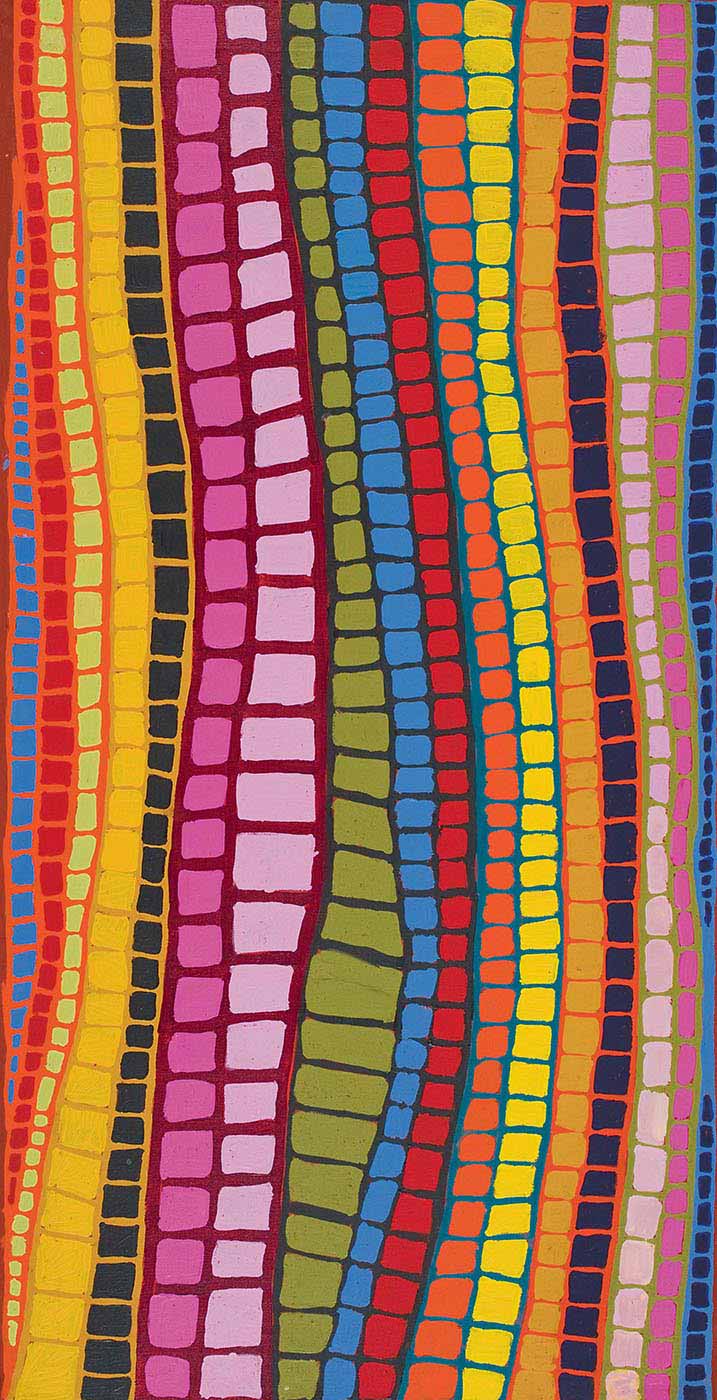

Kalyuyangku by Richard Yukenbarri Tjakamarra

Kulilli by Wimmitji Tjapangarti

Katajilkarr to Kaningarra by Miriam Napanangka

Canning Stock Route Country by Patrick Tjungurrayi

Explore more on Yiwarra Kuju