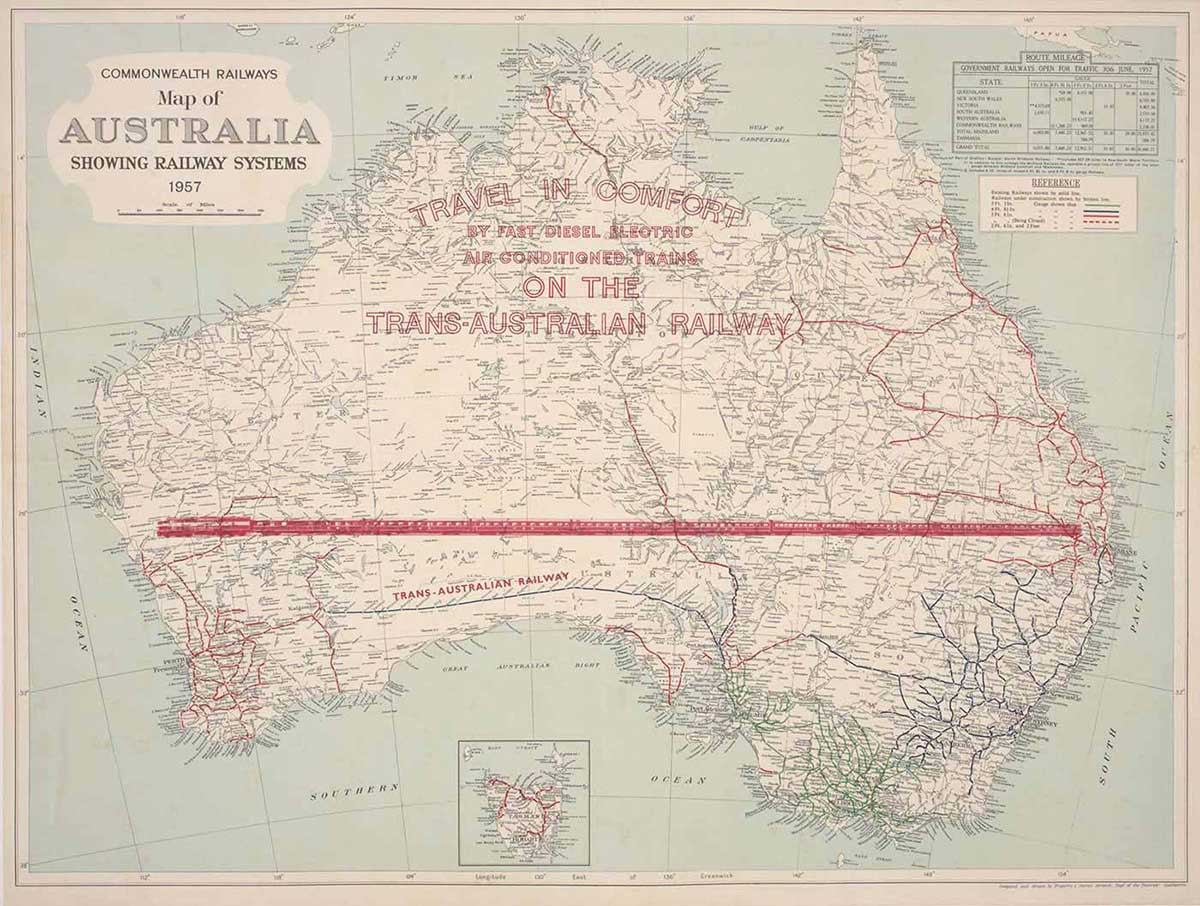

In 1912, work began on a new railway line between Port Augusta in South Australia and Kalgoorlie in Western Australia.

Stretching across 1,693 kilometres of Australia’s driest and most isolated terrain, the Trans-Australian Railway was completed on 17 October 1917, providing a link between the eastern states and Western Australia and helping to give the newly formed Commonwealth a sense of national unity.

Treasurer Sir John Forrest, 17 October 1917:

Today, East and West are indissolubly joined together by bands of steel, and the result must be increased prosperity and happiness for the Australian people.

Joining east and west

The Trans-Australian Railway, running from Port Augusta to Kalgoorlie and connecting the eastern states with Western Australia, was arguably the first major work of a federated Australia.

Before Federation in 1901, Western Australia had made the construction of a railway linking the nation’s eastern and western colonies a condition for joining the Commonwealth.

At the time, the west was linked to the eastern cities only by a rough sea voyage and a single telegraph line. Many argued that this inhibited commerce between the colonies and made it difficult to quickly move troops to defend Australia’s southern and western shores.

In 1907 surveyors and engineers began marking a route across the Nullarbor Plain. Four years later, the Australian Government authorised construction of the railway.

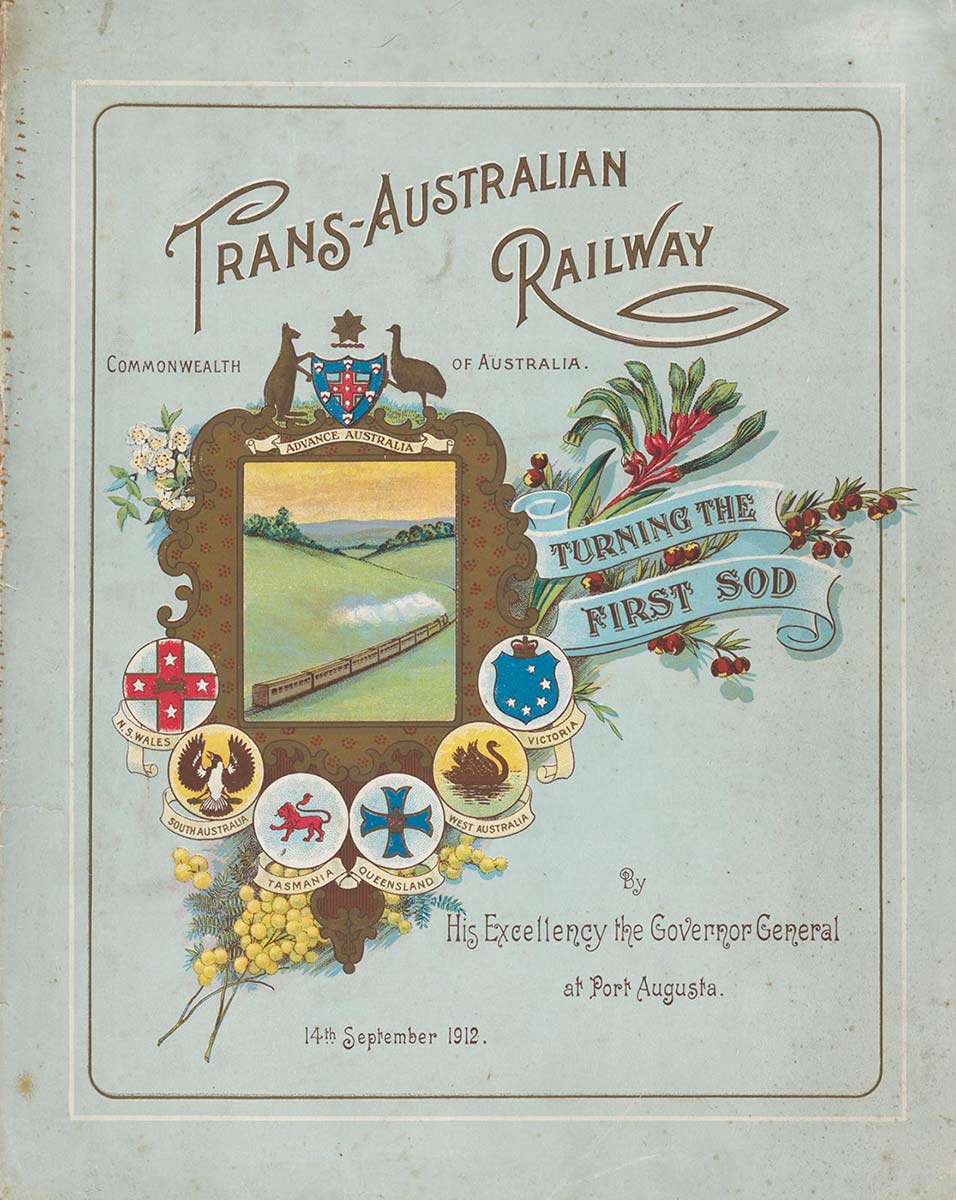

In 1912 Commonwealth Railways was established to oversee the planning and implementation of the Trans-Australian Railway. On 14 September 1912 Governor-General Lord Denman turned the first sod at a ceremony in Port Augusta to officially begin construction of the railway from the eastern end.

Laying the line

Tracks were built simultaneously in both directions, west from Port Augusta and east from Kalgoorlie.

The outbreak of war in 1914 made it difficult for Commonwealth Railways to source labour and materials, but by 1916 more than 3,400 workers were employed on the project.

Maintenance crews lived along the line at intervals, and were supplied by the weekly Tea and Sugar train, which later serviced railway workers and their families.

It took five years for teams of rail workers to lay the 2.5 million hardwood sleepers and 140,000 tonnes of rail needed to finish the 1,693-kilometre job. The last railway spike was hammered into place outside the tiny settlement of Ooldea in remote South Australia on 17 October 1917.

Five days later the first passenger train set off from Port Augusta, arriving at Kalgoorlie 42 hours and 48 minutes later.

Travelling across Australia

The Trans-Australian Railway line radically shortened travel and communication time.

Mail delivery from Adelaide to Perth was cut by two days, and eastbound travellers who took the train arrived in Melbourne three days earlier than those making the journey by ship.

Many people, including federal politicians, theatrical performers and members of the royal family travelled on the line.

They enjoyed the innovation of hot showers installed in the rail carriage, ate meals in the dining cars, sang along to the piano or had a quiet drink in the lounge car before resting in comfort in first-class sleeping cars.

The railway was not only for the wealthy. It also provided Australians with greater opportunities for recreational travel and helped Western Australia become a tourist destination.

In 1969 the standard gauge rail network was extended east from Port Augusta as far as Sydney, and west of Kalgoorlie all the way to Perth, making it possible to catch a train from the Pacific Ocean across the continent to the Indian Ocean.

This led to the naming of the Indian-Pacific, the passenger train that now runs along the line.

New trade

Ooldea, a remote soak among the sandhills that mark the eastern edge of the Nullarbor Plain, is part of the lands of the Kokatha people.

For thousands of years it was the centre of a vast Aboriginal trading network and a reliable source of water.

Ooldea became a vital stopping point for the railway, providing the steam locomotives with fresh water for their boilers.

During the line’s construction, Aboriginal people arriving at the soak began interacting with the rail workers, and by 1917 a semi-permanent settlement had formed.

When a train arrived, Aboriginal people would gather around the passengers’ windows, trading handmade tools such as boomerangs, spears and shields for sweets, money and clothing.

By 1926 servicing the trains had drained the soak dry, and today it no longer supports any population.

Daisy Bates, a self-taught anthropologist, linguist, journalist and author, lived at Ooldea from 1917 until 1934. She worked to provide food, clothing and medical attention to the local Aboriginal community, though the manner in which she conducted her ethnographic and welfare work attracted controversy.

Bates entertained many Trans-Australian Railway visitors to Ooldea. During the 1920s JC Williamson’s theatre company travelled to and from Perth on the railway, and tenor Herbert Browne formed a friendship with Bates, photographing and filming Aboriginal community members, and collecting boomerangs, shields, spears and spear-throwers.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

Burke David, Road through the Wilderness: The Story of the Transcontinental Railway, the First Great Work of Australia’s Federation, New South Wales University Press, Kensington, NSW, 1991.

GH Fearnside, All Stations West: The Story of the Sydney-Perth Standard Gauge Railway, Haldane Publishing, Sydney, 1975.

Daniel Oakman, Martha Sear and Kirsten Wehner (eds), Landmarks: A History of Australia in 33 Places, National Museum of Australia Press, Canberra, 2013.