Cyclone Mahina was the deadliest tropical cyclone in Australia’s recorded history, and probably one of the most intense ever recorded.

More than 300 people died, the great majority of whom were divers and seamen from South-East Asia, the Torres Strait and Pacific islands who worked on the Thursday Island pearling fleet. It was anchored around Bathurst Bay, Queensland, when the cyclone struck.

Queensland Government Meteorologist Clement Wragge’s forecast, The Brisbane Courier, 7 March 1899:

A new tropical disturbance, which we have named ‘Mahina,’ is about 350 miles south-east from Sudest [Vanatinai Island, PNG], and, as it is not improbable that it will make south-westing, shipping along our coast will do well to be on the alert.

Demand for pearl shell

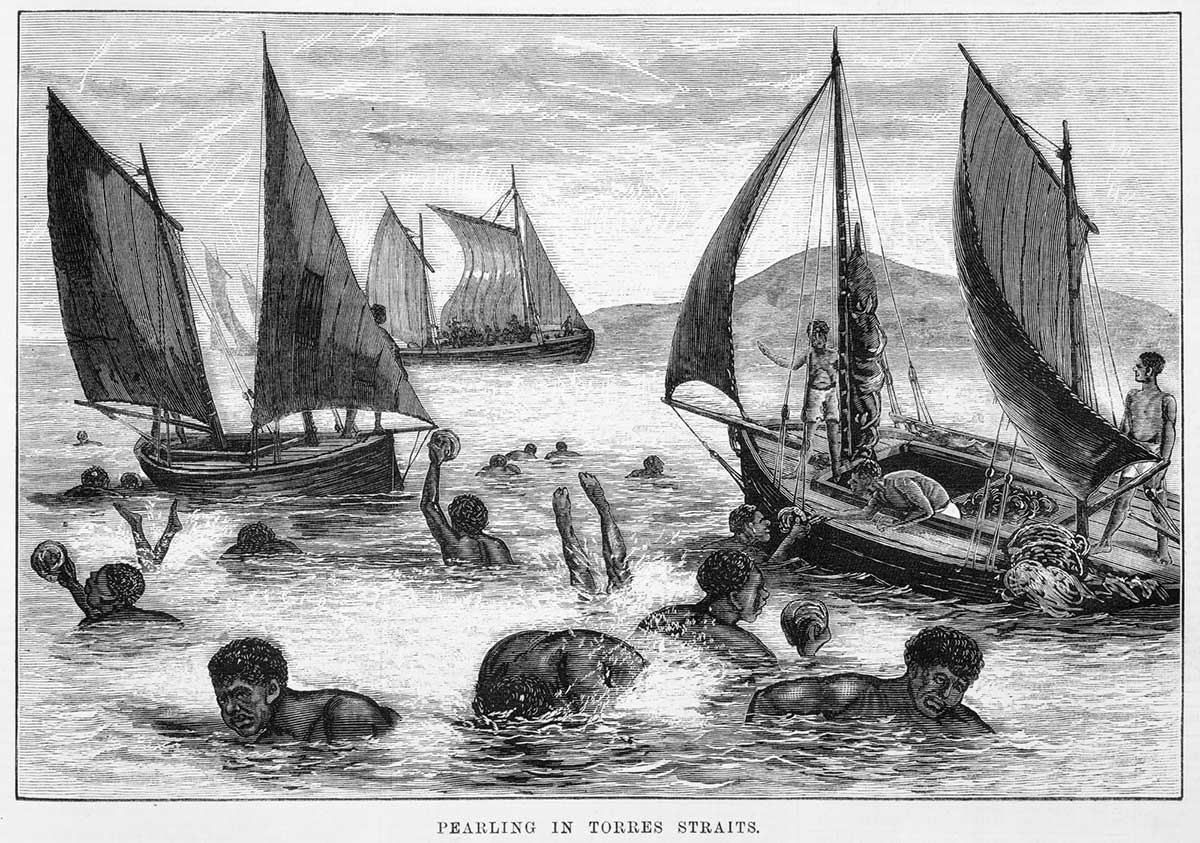

The largest species of pearl oyster, pinctada maxima, was found in abundance in the Torres Strait up to the late mid-19th century.

Its shell had been harvested by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people to use as ornaments and tools for thousands of years.

In the late 19th century pearl oyster shell became highly prized in Europe and North America as material for buttons, furniture inlay, cutlery handles and personal ornaments.

Northern Australia was a major supplier of pearl shell to the world.

Torres Strait industry

In 1869 Captain William Banner from Sydney became the first European to discover commercial quantities of pearl oysters while searching for trepang (sea cucumber) in the Torres Strait, starting the Queensland pearling industry.

Headquartered on Thursday Island, the industry grew rapidly, employing a 2,000-strong multinational and multi-ethic workforce by 1900.

Boat skippers, divers and crew came from the Torres Strait islands, South Pacific islands, South-East Asia, India, Sri Lanka, Japan and the Philippines to work on hundreds of two-masted luggers in fleets owned by companies such as James Clark and Co., based in Brisbane. At the peak of demand in 1889–91, pearl shell was worth £400 (around $60,000 in today’s currency) a ton.

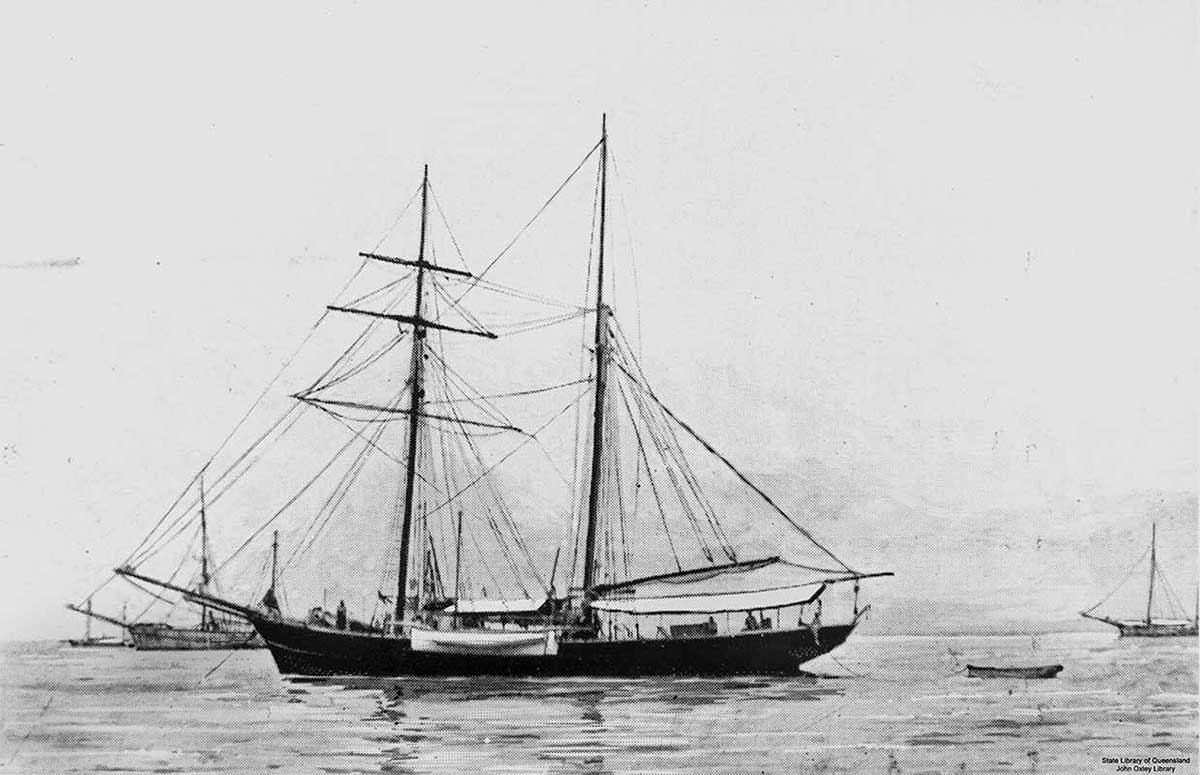

The pearl shell was initially collected from shallow coastal waters. When those stocks were exhausted fleets investigated greater depths, using schooners as floating stations which carried water and other provisions for between 10 to 20 luggers.

Dive suits enabled pearlers to look for shell in waters up to 36-metres deep. The suit comprised a heavy helmet into which oxygen was supplied via a hose; weighted boots kept the operators on the ocean floor.

Divers were tethered to a lugger but were at constant risk of attack by sharks and crocodiles, as well as decompression sickness (‘the bends’).

As with other seafaring occupations of the period, one of the greatest threats to the safety of pearlers was stormy weather.

Weather forecasting

Synoptic weather forecasting (the analysis of many observations taken simultaneously over a wide area) was well understood at the end of the 19th century.

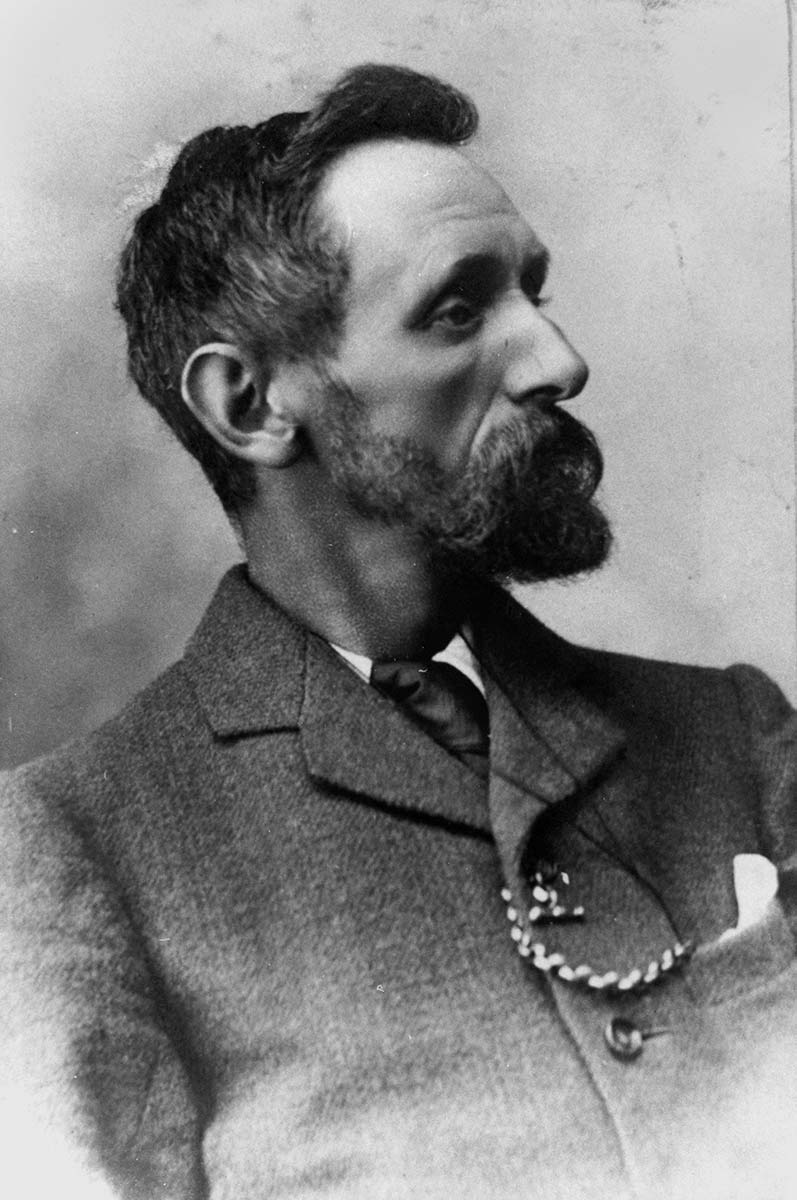

Queensland had a pioneer in this field, Clement Wragge, who as government meteorologist from 1887 to 1902, began the custom of naming weather systems – including after politicians who had annoyed him.

Under Wragge’s management, weather stations reported conditions and barometric pressure readings via the overland telegraph line which connected Brisbane to Thursday Island (via Cooktown).

In 1899, when radio communication was still in its infancy, weather forecasts and warnings were communicated to ships at sea via visual signals from a station.

In Queensland the most northerly coastal signal station was at Grassy Hill, Cooktown. Ship’s captains who were out of range of these signals had to rely on their own experience and barometer readings to predict bad weather and take action to protect their crew and vessels.

Clement Wragge, 11 March 1899:

Much, indeed, do we regret that we have no means of advising the lightships and pearling fleets of the approach of storms between Cooktown and Torres Straits.

Cyclone Mahina develops

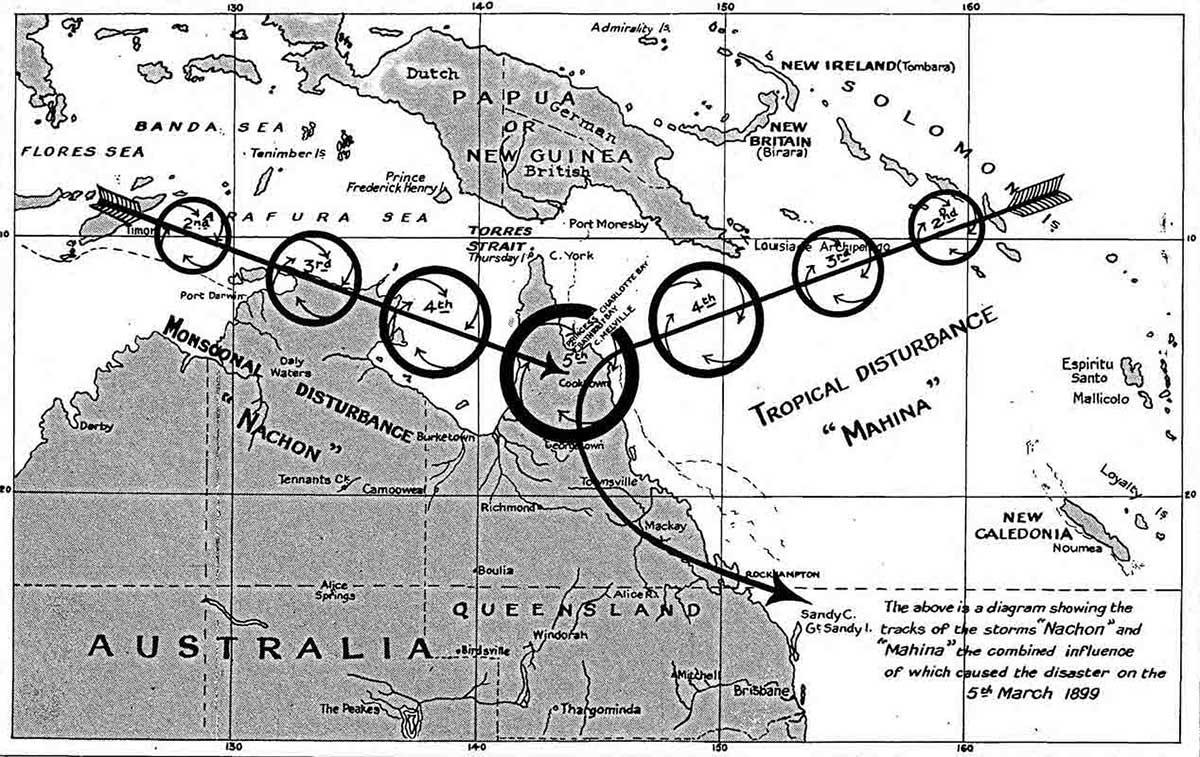

On 3 March Clement Wragge described conditions between Papua New Guinea and New Caledonia as ‘suspicious’.

In his forecast on 6 March 1899 Wragge named a new tropical disturbance developing southeast of Sudest (Vanatinai Island, Papua New Guinea), Cyclone Mahina. He also noted the development of a second cyclone, Nachon, in the Gulf of Carpentaria.

On 8 March Wragge wrote that he ‘feared Mahina will not prove as soft and gentle as the Tahitian maiden of that name, for it is likely to give us some trouble. Special warnings have again been sent to all coast towns and the storm signals have been hoisted for the benefit of shipping’.

However, Tropical Cyclone Mahina had already hit Bathurst Bay (167 kilometres north of Cooktown) around 11pm on Saturday 4 March. It was over by 10am the next morning.

Australia’s most deadly cyclone

When Mahina struck, there were about 1,000 men, women and children on board around eight schooners and more than 100 luggers anchored in the Princess Charlotte Bay and Bathurst Bay area to offload shell.

More than half of the fleet was destroyed during the night, and at least 307 people were killed.

Of the Bathurst Bay schooners, only Crest of the Wave survived because its captain, William Porter, a New Zealander, cut down its mast to prevent it from capsizing.

The cyclone produced huge seas and a surge of water which swept far inland.

According to a contemporary account of Cyclone Mahina, The Pearling Disaster, 1899: A Memorial (written by the family of one of its victims), Constable John Kenny of the Queensland Native Mounted Police was camped with four Indigenous troopers near Ninian Bay, about 40 feet (12 metres) above sea level and about half a mile (800 metres) inland, when they were inundated by sea water to waist-depth.

It is not known whether any Indigenous people died in the inundation, although there were reports that some had been swept out to sea.

Witnesses who visited the area shortly afterwards, reported seeing grass ripped from the ground and dolphin carcasses six metres above sea level.

Stories of heroism and stamina

A British East India ship, The Duke of Norfolk, was the first to reach the area on 5 March, and picked up Captain Porter’s wife and baby from their schooner.

Despite Porter having reported the destruction of the pearling fleet, The Duke of Norfolk did not actively search for other survivors.

News of the cyclone did not reach Brisbane until 8 March, and a rescue effort was launched two days later. The local Indigenous people had already buried the many bodies that had washed up on shore.

Nevertheless, some people did survive, and newspaper reports carried stories of men and women swimming for days to reach land, with people who could not swim supported on their backs.

Cylcone Mahina in the record books

Mahina was a Category 5 cyclone, as are all cyclones with a central pressure of 929 hectopascals (hPa) or less. Cyclone Tracy had a pressure of 950 hPA and Cyclone Yasi, which crossed the North Queensland coast in 2011, registered 929 hPA. The storm with the lowest recorded pressure (870 hPa) was Typhoon Tip in 1979.

According to The Pearling Disaster, 1899, at Mahina’s peak Captain Porter took a barometric pressure reading of 27 inches of mercury (inHg), equal to 914 hPa. Recently, researchers have found historical evidence to suggest that Porter actually recorded a much lower pressure – 26 inches (880 hPa) – but that no-one at the time believed such a measure was possible.

If the pressure of Mahina did fall to 880 hPa, this would make it one of the most intense tropical cyclones ever recorded and, according to current research, capable of producing a sea-water inundation of 13 metres.

Explore defining moments

You may also like

References

Tropical cyclone knowledge centre, Bureau of Meteorology

Jeff Callaghan, ‘The Bathurst Bay hurricane, March 1899’, in Harden Up: Protecting Queensland, 2011.

Jonathan Nott, Camilla Green, Ian Townsend and Jeffrey Callaghan, ‘The world record storm surge and the most intense Southern Hemisphere tropical cyclone: New evidence and modelling’, American Meteorological Society, May 2014.

Norman Pixley, ‘Pearlers of North Australia: The romantic story of the diving fleets’, in Royal Historical Society of Queensland, vol. 9, no. 3, 1972, pp. 9–29.

Ian Townsend, The Devil’s Eye, HarperCollins, Sydney, 2008.