In the middle of the night on 24 June 1852 a catastrophic flood swept through the New South Wales town of Gundagai.

The water rose quickly to become a raging torrent that swept whole buildings away and left people clinging for their lives in trees.

Only three buildings were left standing when the water receded. Between 80 and 100 people died, and the disaster remains the deadliest flood in Australia’s recorded history.

Sydney Morning Herald, 5 July 1852:

One of the most fearful catastrophes which it has ever been our lot to record … the village of Gundagai has been almost entirely destroyed.

Floods in Australia

When Europeans arrived in Australia they were confounded by the river systems. Unlike the rivers of northern Europe, Australian rivers flowed, dried up and flooded in no apparent cycle.

For First Nations people, attuned to their country, frequent flooding brought benefits by replenishing the environment and bringing a bounty of food. In south-east Australia, in Wiradjuri land, the Murrumbidgee River was a major source of food. In Wiradjuri language the word ‘murrumbidgee’ means ‘big water’ or ‘plenty water’.

Town built on a flood plain

First Nations people have lived in the area now known as Gundagai for at least 50,000 years. The river flats were used by the Wiradjuri people as a camping and meeting place and hunting ground. Several scarred trees and a bora ring used for ceremonies remain today.

The first Europeans to reach the area was an expedition led by explorers Hamilton Hume and William Hovell who passed through in 1824 while creating a route from Sydney to Port Phillip (Melbourne). The site that became Old Gundagai was a natural place to cross the Murrumbidgee River.

By 1836 the area was being used as a squatting run by early pastoralists. The site was surveyed on the low-lying river flats and a town plan was drawn up.

Gundagai was gazetted as a township in 1838, by which time settlers were already building on the river flats. Warnings from the local Wiradjuri people that the area was prone to flooding were ignored.

Gundagai grew quickly as a service town for travellers and pastoralists. A punt service, established at Stuckey’s Crossing in 1838, was the only place to cross Murrumbidgee River on the route between Sydney and Melbourne.

During Gundagai’s early years, the Murrumbidgee River flooded several times. In 1844 a flood claimed two lives and caused extensive damage.

Gundagai residents grew concerned about the town’s location and petitioned the New South Wales government for help. However, there was a view within the government that the ‘big one’ was behind them and no moves were made to relocate the settlement.

The great flood

On Thursday 24 June 1852, after weeks of heavy rain, the Murrumbidgee River broke its banks and surged into Gundagai. In previous floods, residents sought shelter in their attics and on rooftops. This time the water rose rapidly and soon there was no escape. The island that Gundagai had become was sinking fast.

By midnight, under a full moon, the flood waters became a raging torrent. Whole buildings were swept away. For the terrified residents, the treetops became the only things left to hold on to. Some people clung on for two nights before losing their grip and being swept away. Others died from exhaustion in the branches.

Estimates of the death toll are between 80 and 100 people, more than one third of Gundagai’s population of about 250.

It remains Australia’s deadliest flood. The final death toll will never be known, as it was not known how many travellers were in town. Bodies were discovered for months afterwards. At least 35 of the victims were children; the youngest was only three weeks old.

The Sydney Morning Herald’s Gundagai correspondent clung to a treetop until he was rescued. He reported:

As night drew in the unavailing cries for assistance all around became fearfully harassing. Crash after crash announced the fall of a house and the screams that followed the engulphing of those who clung.

Wiradjuri heroes

The death toll would have been much higher if not for the heroic efforts of local Wiradjuri men. Of the four men involved, only two are known by name, Yarri (Yarrie or Yarra) and Jackey (Jacky or Jacky Jacky).

Over three days they navigated the treacherous waters in a bark canoe and a rowboat, pulling survivors from the trees.

Wiradjuri men were renowned for their skilful use of bark canoes. Such canoes were only able to carry one passenger, so Yarri made many trips, taking people one at a time. He rescued 49 people while Jackey rescued 20 using a rowboat.

The Wiradjuri people had been decimated by introduced diseases including smallpox, tuberculosis and measles, and violence as they were displaced from their homelands, but they did not hesitate to rescue the settlers when disaster struck.

Aftermath of the flood

Sydney Morning Herald, 24 July 1852:

The scenes … are truly distressing. At every step you see someone lamenting the dead. Here and there the sorrowing remains, of what three days before was a large and thriving family.

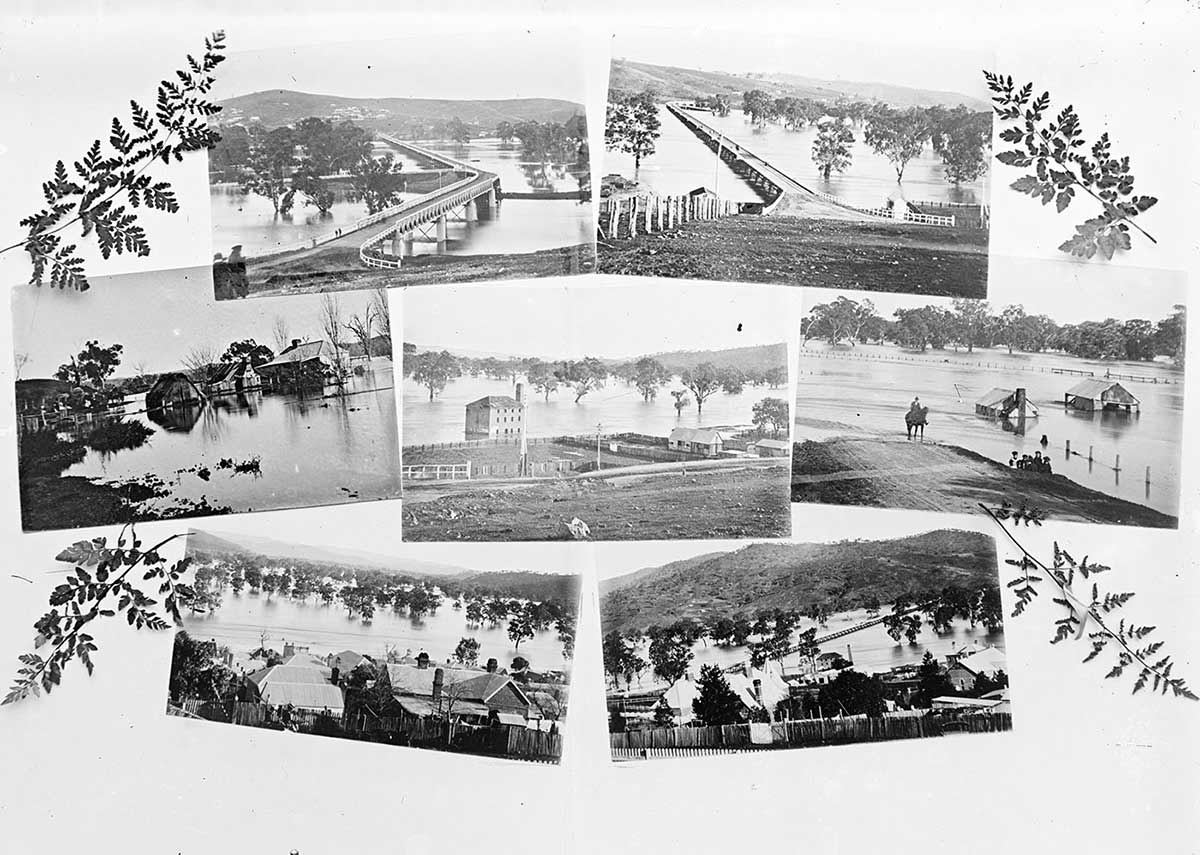

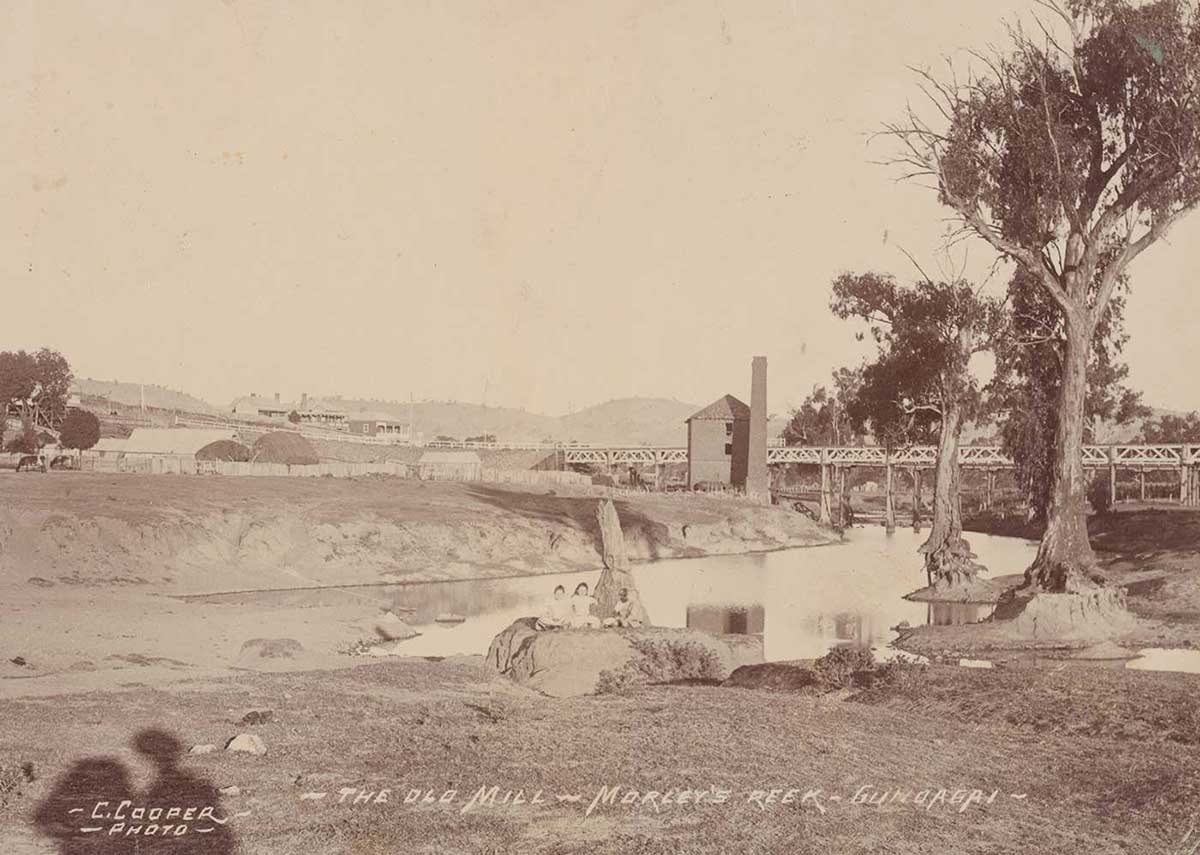

Of the 78 buildings on the Gundagai flat, 48 were completely swept away and the rest were irreparably damaged. The town’s flour mill was one of only three buildings still intact.

Throughout the colony there was an outpouring of sadness. Anger was directed at the NSW Government for short-sighted town planning.

In October 1852 the government gave in to mounting pressure and agreed to exchange any allotments at risk of flooding for land on higher ground.

By the end of 1859 the old town was completely abandoned and Gundagai was settled on the slopes of Mount Parnassus, where it remains today.

Legend of Gundagai rescue

It was years before Yarri and Jackey received any recognition for their heroic acts. In 1875 they were given an engraved breastplate each, and granted a lifelong pension from the settlers.

Their story lives on in oral history and poetry, and in the descendants of those who were saved by the men. In 2017, on the 165th anniversary of the great flood, Gundagai unveiled a bronze sculpture of Yarri and Jackey with a bark canoe.

In our collection

Explore defining moments

References

Emily O’Gorman, Flood Country: An environmental history of the Murray-Darling basin, electronic resource, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, VIC, 2012.

Brendan O’Keefe, Michael Pearson and Marcia McIntyre, The Watermen of Gundagai, The Old Gundagai Publishing Committee, Gundagai, NSW, 2002.

Cliff Butcher, Gundagai: A Track Winding Back, A C Butcher, Gundagai, 2002.

David Lindley, Early Gundagai, T Greensmith & Co. Publishers, 2002.

Allen Crooks, Yarri: Hero of Gundagai, Oxford Printery, Wagga Wagga, NSW, 1993.