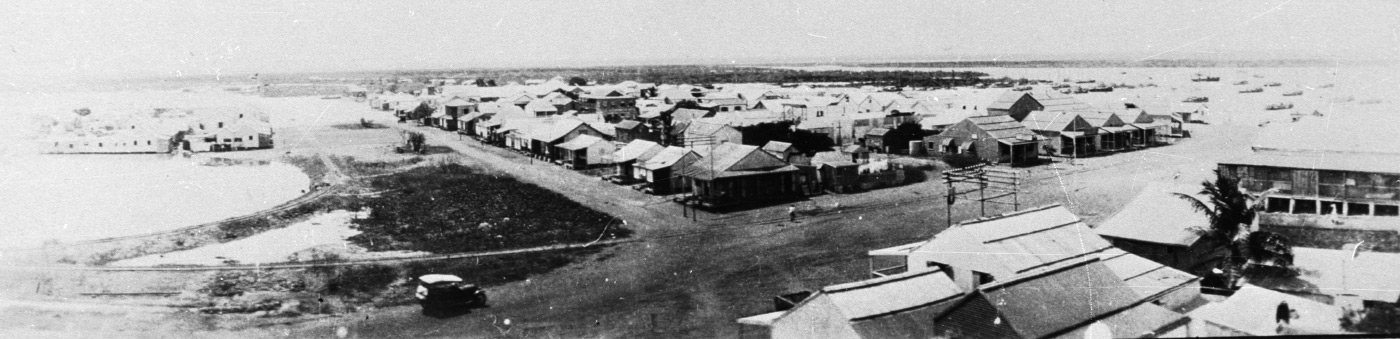

In the summer of 1888–89 Broome, a recently founded town in the far north-west of Western Australia, became the centre of the colony’s pearling industry. The most successful divers were Malays, Timorese and, especially, Japanese.

Report of the Government Resident at Thursday Island for 1894–95, on the death of a Japanese diver in the Torres Strait:

Such is the craving for ‘more shell’ when it has once got possession of a diver’s imagination – I held an inquiry a few days ago into the causes connected with the death of one Wattanabi, an old and experienced diver. His last remark was ... ‘I’m sorry I am going – the water is clear, and I could have got plenty of shell’. The ruling passion is thus evidenced as strong even in death.

The pearling industry in Australia

The pearling industry used divers to collect naturally occurring pearls – and pearl shell, from which decorative mother-of-pearl was made – from the bottom of the sea.

In Australia the industry started in the Torres Strait, where the waters were shallow enough that the divers – mostly Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – could dive by holding their breath.

But as pearl shells in shallow waters were fished out, divers had to go deeper, wearing breathing equipment which Aboriginal divers often disliked.

By the 1860s there was also pearling in Western Australia. At first this was based at Cossack, now a ghost town 800 kilometres south-west of Broome. But at the end of the 1880s Broome became the most important centre.

Around the same time the underwater telegraph cable which linked Australia with the world was relocated so that it emerged at Broome’s Cable Beach.

Dangerous diving in deep waters

By the 1870s the exhaustion of shell in shallow waters forced divers to exploit beds in deeper water.

They used German-designed equipment, including a helmet and a wire-reinforced rubber air hose, supplied by a hand-operated air pump on the boat.

Each boat, or lugger, had only one or two divers. Just one diver would go down at a time. One of the other five or six crewmen, the tender, helped the diver into his gear, including a canvas suit and steel corselet.

The diver climbed into the sea, weighted down by 6.3-kilogram boots and 50 kilograms of lead lashed to his body.

Holding his air hose and a rope, he walked on the seabed spotting and picking up shells. He communicated with the boat by a coded set of tugs on the rope, which was also used to haul both diver and shells back to the boat.

Each dive was quite short, generally between five and 20 minutes on the ocean floor.

Boats spent weeks or months at sea. Crews slept in tiny 1.4-metre-high cabins. The boats were infested with cockroaches, food was monotonous and at close quarters tempers could be stretched.

In the Torres Strait and at Cossack divers generally only had to go down 5 to 10 fathoms (9 to 18 metres). But the rich pearl shell beds at Broome lay 20 to 25 fathoms underwater (36 to 45 metres). This meant the diving was much more dangerous.

If divers came up too quickly they would suffer from ‘diver’s paralysis’, or the ‘bends’, caused by bubbles of nitrogen entering bodily tissues. The result was agonising pain and, all too often, death.

Only in 1912 were Royal Navy ‘staging’ tables adopted in Australia to try and ensure a safe rate of ascent. Even then they were often ignored. Divers often suffered from rheumatism. Other dangers included sharks, hidden holes on the sea floor and snagged safety lines.

Japanese divers in Broome

Most of the successful divers were Japanese, along with Timorese and Malays. There were some European divers, but generally they were less successful and less well regarded. In 1912, 10 experienced British deep-sea divers arrived in Broome. Within 18 months, three were dead and the rest had left for other work.

In 1916 a Royal Commission into the industry recommended that Europeans should not be encouraged to enter such an arduous and dangerous occupation. But it was dangerous and arduous for the Japanese too. In any given year more than one in 10 of the Japanese divers died.

In 1979 there were a thousand names legible on tombstones in the Japanese cemetery at Broome. Half of them died in their twenties. Many other names will have been lost. Conditions were so bad that the Japanese Government periodically tried to discourage recruitment (and many crew members had to go to Singapore to be signed up).

The Japanese divers were in high demand. They were noted for their energy and endurance, working from dawn till dusk, making up to 50 dives a day and staying at sea for up to four months.

Many Japanese divers came from Wakayama prefecture, an agriculturally poor coastal area south of Osaka. Many of its people were fishermen, and quite a few had experience diving for abalone. Pearling, although dangerous, offered potentially lucrative returns.

But it was a gamble. As foreign contract labour, Japanese divers were not covered by Australian workers’ compensation. Actual gambling was also a significant temptation. But those who succeeded and returned home with their earnings became prosperous members of their communities.

Australian paranoia

Since Australians were reluctant to work on the luggers, the pearling industry relied on Asian labour. Because the industry was a lucrative one, exceptions were made to the White Australia policy.

Nevertheless, white paranoia led to laws trying to limit the proportion of crew members who could be Japanese. There were also attempts to stop Japanese from owning pearling boats.

The divers were not the only Japanese migrants. Some Japanese sex workers, working in Sheba Lane in Broome, earned enough money to buy shares in pearling boats. In 1910 a Japanese doctor arrived, and the following year set up a hospital.

There were tensions not only between Australians and Japanese, but also between Japanese and other Asian groups. There was a strong racial hierarchy in Broome, with whites at the top, then Japanese, and other Asians and Aboriginal people beneath them. This resulted in street fighting and riots in 1907, 1914 and 1920.

The Japanese in the town were interned during the Second World War. Some Japanese divers returned in the 1950s, despite some local opposition. (An attempt to replace them with Greek sponge divers failed because the diving was quite different.)

The cultural influence of the Japanese remained in Broome, and Taiji, a town in Wakayama prefecture, has been a sister city of Broome since 1981.

In our collection

Explore defining moments

You may also like

References

Mary Albertus Bain, Full Fathom Five, Perth, Artlook Books, 1982.

David Black and Sachiko Sone (eds), An Enduring Friendship: Western Australia and Japan – Past, Present and Future, Crawley, Westerly Centre, University of Western Australia, 2009.

DCS Sissons, ‘The Japanese in the Australian pearling industry’, Queensland Heritage, vol. 3, no. 10, May 1979, pp. 8–27.