After more than a decade of effort, the Victorian Government wrested control of the colonial school system from religious denominations, and passed the Education Act 1872.

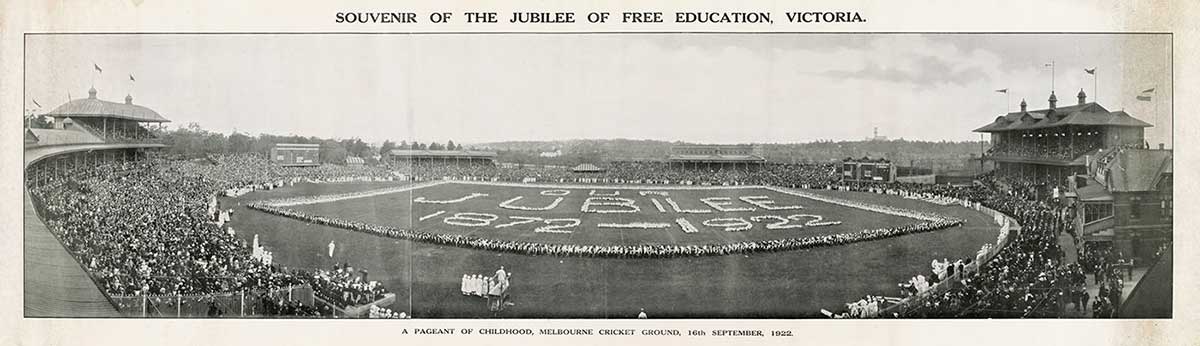

The legislation made Victoria the first Australian colony (and one of the first jurisdictions in the world) to offer free, secular and compulsory education to its children.

Charles H Pearson, education reformer:

I need not here go over the old ground that an educated community is on the whole moral, more law abiding and more capable of work than an uneducated one.

Early education in the colony

At its separation from the Colony of New South Wales in 1851, Victoria inherited two types of schools: denominational or church-organised, and national or nonsectarian-organised.

The colonial government supported both, and each had a Melbourne-based school board.

In both cases, schools were created when the local community could provide a minimum number of students and raise a portion of the school building costs. Then the government would assist by providing land, completing financing for the school’s construction and paying a teacher’s salary.

As long as the school taught from a prescribed range of subjects and texts and passed standard inspections, the community could nominate the teacher and regulate his or her conduct.

In general, it was the churches, with their existing physical and communal structures, that had the greater ability to organise people around education, and so denominational schools dominated the education system until the 1850s.

However, this system proved inefficient and divisive as the mutually antagonistic Catholic Church and the multiple Protestant denominations duplicated schools and services across the colony. With the massive influx in population after the 1851 gold rush, it was apparent that the provision of education needed to change.

Victoria in the mid-19th century was a hotbed of liberalism and its political commitment to public education, public health and social welfare was gradually reflected in the increasing involvement of the colonial government in these areas.

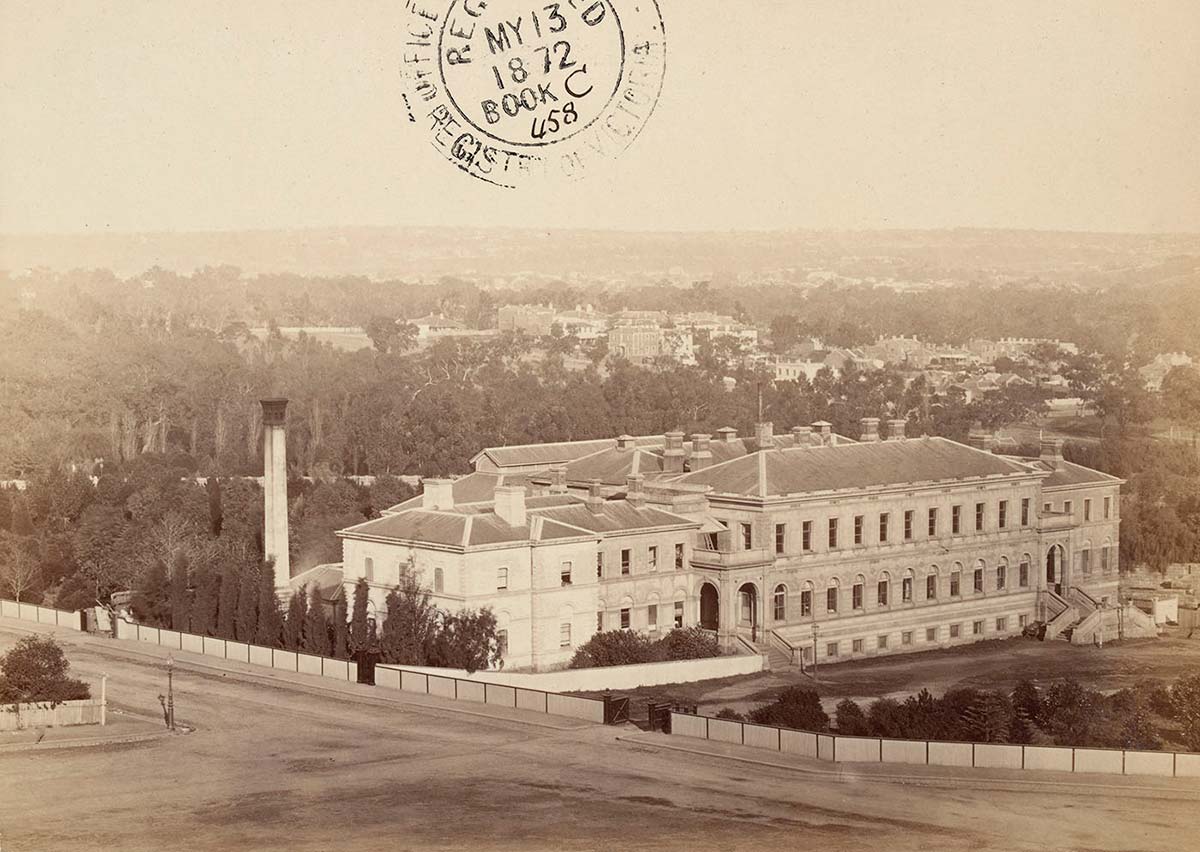

In 1862, through the Common Schools Act, the Victorian Parliament abolished the two existing centralised boards and created a single Board of Education.

However, the Board continued to fund religious schools and its executive became dominated by denominational representatives who maintained the dual system of instruction that the government was trying to abolish.

1866 Royal Commission

Frustration with the perpetuation of the old, inefficient structure led the government of James McCulloch to establish a royal commission into the operation of the Common Schools Act.

The royal commission, chaired by the Attorney-General George Higinbotham, was made up of representatives from all major religious denominations except the Roman Catholics who chose not to take part. Between September 1866 and January 1867, the commission met for 52 sittings.

By the end of this, Higinbotham had managed to persuade the commissioners to support his proposal for a comprehensive system of non-sectarian, state-funded schools.

However, the Protestant–Catholic division was widening and the commission’s proposal to teach a 'common Christianity' led to further separation.

The Catholic Church would not endorse the recommendations and without the largest single private supplier of education willing to institute a new system, the Protestant denominations removed their backing for the commission's proposal.

Higinbotham’s royal commission recommendations for a colony-wide system of non-sectarian state-funded schools was crafted into a Bill to parliament, but the tide of support had turned.

As Higinbotham said, 'a national system of religious education is at present rendered impractical by the ecclesiastical rivalry and dissensions and by the unpatriotic policy pursued by the leading Christian sects'.

The future premier Charles Gavan Duffy marshalled Catholic opposition to the Bill that came before Parliament, and it was defeated in May 1867.

1872 Education Act

The Education Act 1872 revisited the recommendations of the 1866 Royal Commission but its passage into law was a result of political machinations around that year’s colonial election.

The protectionist and free trader parliamentary factions needed a common platform to rally around and overthrow the Duffy government. Opposition to government aid to religious schools was the galvanising topic that brought these traditional rivals together, and it became a major election issue.

In answer to calls for the cancellation of state aid to religious schools, the Bishop of Melbourne, James Goold, issued a pastoral admonition to be read in every Catholic Church. It read:

They boldly and defiantly tell you it is their determination to do away with your Schools and substitute them for Godless schools to which they will compel you under penalty (or imprisonment) to send your children.

The Catholic Church directly encouraged its congregations to withhold votes from candidates that supported, ‘godless compulsory education’. But the Admonition backfired and galvanised the anti-Catholic opposition, which brought about the downfall of the Duffy government.

One of the first propositions of James Francis, the newly elected premier, was for reform to education along the lines of the 1866 Royal Commission. The new Education Act was passed on 17 December 1872.

Under the Act, the Board of Education was replaced by a departmental structure under a Minister of Public Instruction directly responsible to parliament. It also stated:

In every state school secular instruction only shall be given and no teacher shall give any other than secular instruction in any state school building …

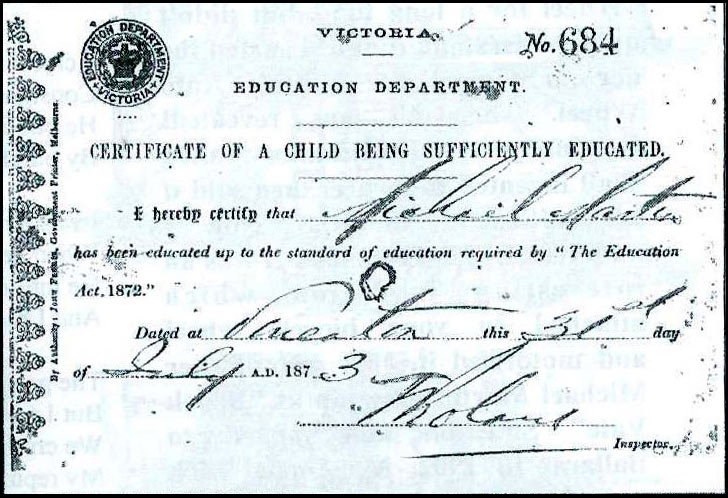

Children between the ages of six and 15 were obliged to attend school and their education was free.

In addition, all government funding to church schools ceased. Most of the religious denominations, with the exception of the Roman Catholics, allowed their schools to form part of this new system.

The Education Act, although contentious and accused of being politically motivated, was the first of its kind in the Australian colonies, and Victoria became one of the first regions in the world to offer free, secular and compulsory education.

By the end of the century, Victoria was directing a higher proportion of resources into public schools and educating a higher per-capita number of children than European countries.

The number of state schools tripled between 1871 and 1876, while at the same time church schools dropped from teaching a majority of students to teaching less than a quarter.

The Catholic school system continued but public schooling became the backbone of the Australian education system. The movement spread across the country and by 1908 all the colonies had centralised government departments administering free, compulsory and secular education.

You may also like

References

Charles Gavan Duffy, Australian Dictionary of Biography

George Higinbotham, Australian Dictionary of Biography

Craig Campbell and Helen Proctor, A History of Australian Schooling, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, 2014.

Stuart MacIntyre, A Colonial Liberalism, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1991.