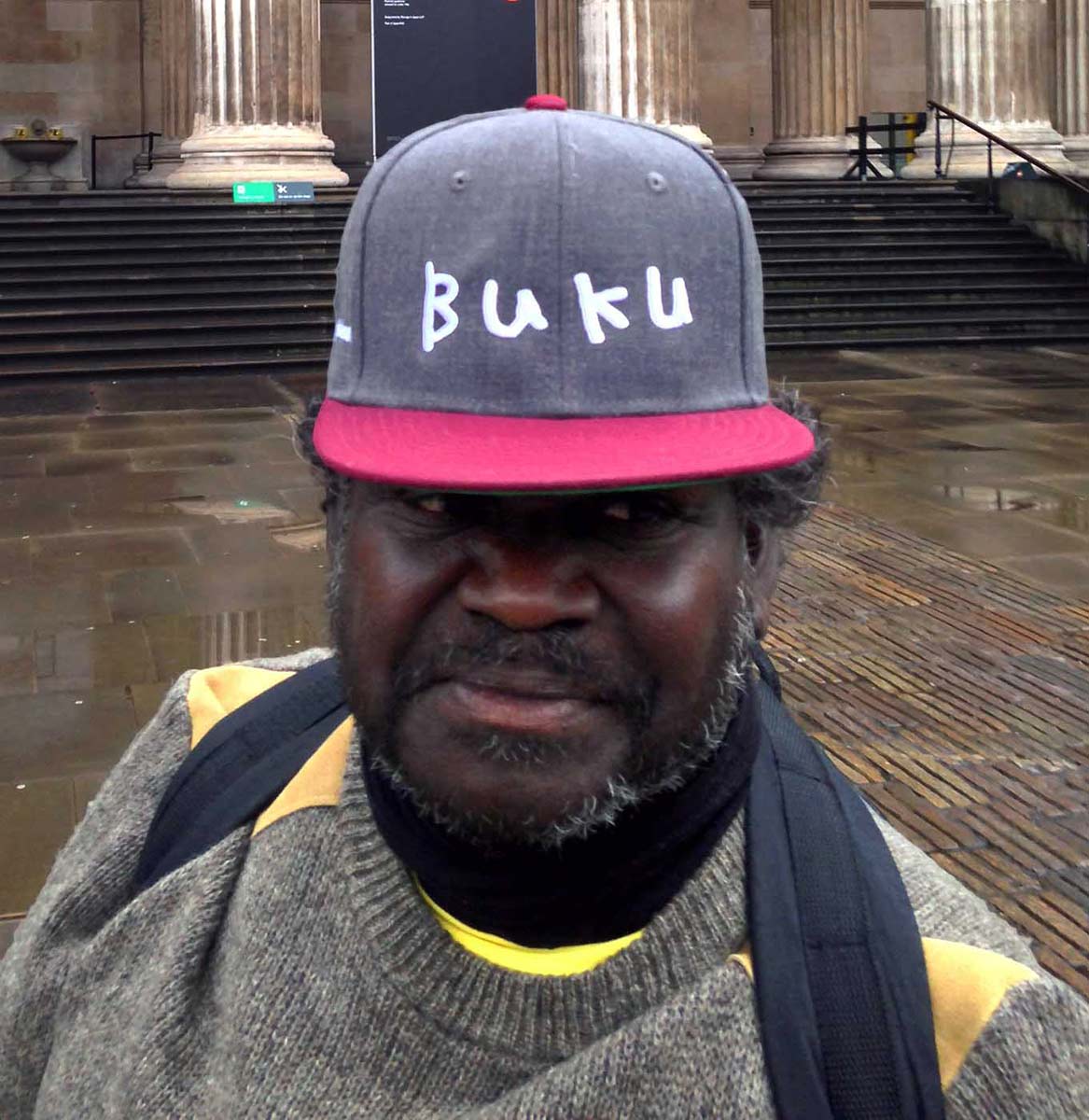

Mr Wanambi’s father Mithili Mr Wanambi was a painter, but he died before Mr Wanambi was able to learn from him to any great degree. Mr Wanambi began painting in 1997 as part of a major artistic program called the Saltwater Project. His arm of the Marrakulu clan (of the Yolŋu people in Arnhem Land) is responsible for saltwater imagery, which had not been painted intensively since his father’s death in 1981.

Mr Wanambi drew on the knowledge of caretakers, or djunggayi (men who teach younger men their lore and how to paint designs), principally the late Yanggarriny Wunungmurra (1932–2003). This entitled Mr Wanambi to paint saltwater designs, some of which were outside even his father’s public painting repertoire.

Mr Wanambi was educated at Dhupuma College and Nhulunbuy High School and worked as a NSW Department of Sport and Recreation officer, a probation and parole officer and at the local mine. He has five children and is a grandfather. His wife Warraynga is also an artist.

Mr Wanambi’s first bark won the 1998 NATSIAA Best Bark award. Mr Wanambi went on to establish a high-profile career. In the 2003 NATSIAA awards, a sculpted larrakitj by Mr Wanambi was Highly Commended in the 3D category. Since then he has been included in many prestigious collections.

He had his first solo show at Raft Artspace in Darwin in 2004 followed by solo shows at Niagara Galleries, Melbourne in 2005 and 2008. Mr Wanambi has been heavily involved in many major communal projects of this decade including a major commission by the Sydney Opera House, the opening of the National Museum of Australia, the Wukidi ceremony in the Darwin Supreme Court and the films: Lonely Boy Richard, The Pilot’s Funeral and Dhakiyarr versus the King.

Mr Wanambi was actively involved in community recreation and health projects. In 2008 he was commissioned to provide a design for installation on a seven-storey glass façade in the Darwin Waterfront Development. He became a director of Buku-Larrnggay’s media centre, The Mulka Project, in 2007. In this role, he facilitatedmedia projects such as the Nhama DVD, and mentored young Yolŋu in accessing training and employment in the media centre.

Mr Wanambi died in 2022.

Mr Wanambi:

My history is alive today. My history keeps on building up. My identity is stronger. It is not dying. The more I share, the stronger I get. The more power I get. That’s why, when we put a larrakitj as a piece in a museum, it has got the power.

Artwork description

Larrakitj are hollow log coffins made from stringy-bark trees that are naturally hollowed out by termites. Painted in natural earth pigment, Mr Wanambi's larrakitj display saltwater imagery and convey creation and ancestral stories. In this contemporary setting, these timeless poles show the strength and power of Yolŋu culture.

Mr Wanambi said this about his larrakitj:

The outside surface of things hides what is inside. I want to share what is hidden. In Yolŋu, understanding the life of the spirit is a circle. The larrakitj is a circle. We are looking for our identity and we search around and around until we find our destiny and we go straight to that circle and join it and become a part of family.

We used larrakitj as a coffin but now instead of digging it in the ground we want to show it as art. We believe that the spirit travels through the water and returns to its source and then is born anew. The body dissolves and the bones return to the land as the larrakitj decays. I have wanted to share this understanding with non-Indigenous people for a long time. To show them what is inside. Inside the larrakitj. Inside our destiny. Inside our hearts.

Also, what is inside a memorial pole and what is under the paint? The stringy-bark tree, known as gadayka in ordinary language, has sacred names: Wanambi, Binykurrngu, Mawulul. It is the image/spirit of a person of my clan, the Marrakulu. There are sacred names for this [spirit]: Djoluwa, Gatjinydji, Dhaltangu. We sing all of the cycle of that tree including when it falls. The honey, the blossom, the buds. It dances like us.

When the tree falls, the honey spills forth like the Gurka’wuy River flooding into the sea at Trial Bay [off north-eastern Arnhem Land, Northern Territory]. This is in the water here. In these designs where the Marrakulu clan meet their mother’s mother, the Balamumu. There are statues in this water made of giant boulders that have names.

And also these fish of the species Darrapa, Warrwada and Warrwitjpal. They are the ancestors of the land. They come to the rock and their path is blocked. They can jump into the air. They land back into the water. Their spiritual pathway continues. It is a cycle.

Reflections

Mr Wanambi on his visit to the British Museum:

There is a difference between a normal museum and an overseas museum. I feel manymak (good) sharing Yolŋu madayin (sacred Law) into English culture. England has sacred objects from other cultures. I want England to understand that we have a Law. I am happy to show our work because we are promoting Yolŋu culture into other worlds. To make them aware that we use a different colour. The colour we use is the same one we use on the painted bodies when someone dies, at a dhapi (circumcision) or in bunggul (ceremonial dance). The painting on the bodies is related to the designs in the artwork.

In Ngapaki (non-Yolŋu) way, they don’t have that kind of thing. Their colour is different. In Yolŋu culture, that design is like a written language. When you see the designs it tells you which songs are being sung. And those songs have words. If you wanted to, you could write them down. But we don’t have to because they are already written in the designs.

The ritual is on the munata (ground) and everything comes from that ground. The identity that we have is in our ground. Yingapungapu and Molk are sacred sand sculptures which come out of the ground and they bring that foundation into the designs. And from there it comes to the song cycle.

So I am happy seeing the work in the British Museum. My only objection would be if they held the sacred objects, bones or human remains against the wishes of whichever culture those people came from.

I enjoyed meeting Prince Charles and it was great that he came to open the Indigenous Australia: enduring civilisation exhibition.

There were a lot of white walls in [the British Museum] and if it was my choice I would prefer to see a jigsaw puzzle of paintings from all the different countries covering all the walls.

My history is alive today. My history keeps on building up. My identity is stronger. It is not dying. The more I share, the stronger I get. The more power I get. That’s why when we put a larrakitj as a piece in the National Museum of Australia it has got the power.

Explore the other artists