Australia played an important role in the establishment of the United Nations. The countries involved hoped that the UN’s formation would prevent a repeat of the Second World War, the horrors of which were still very fresh in their minds.

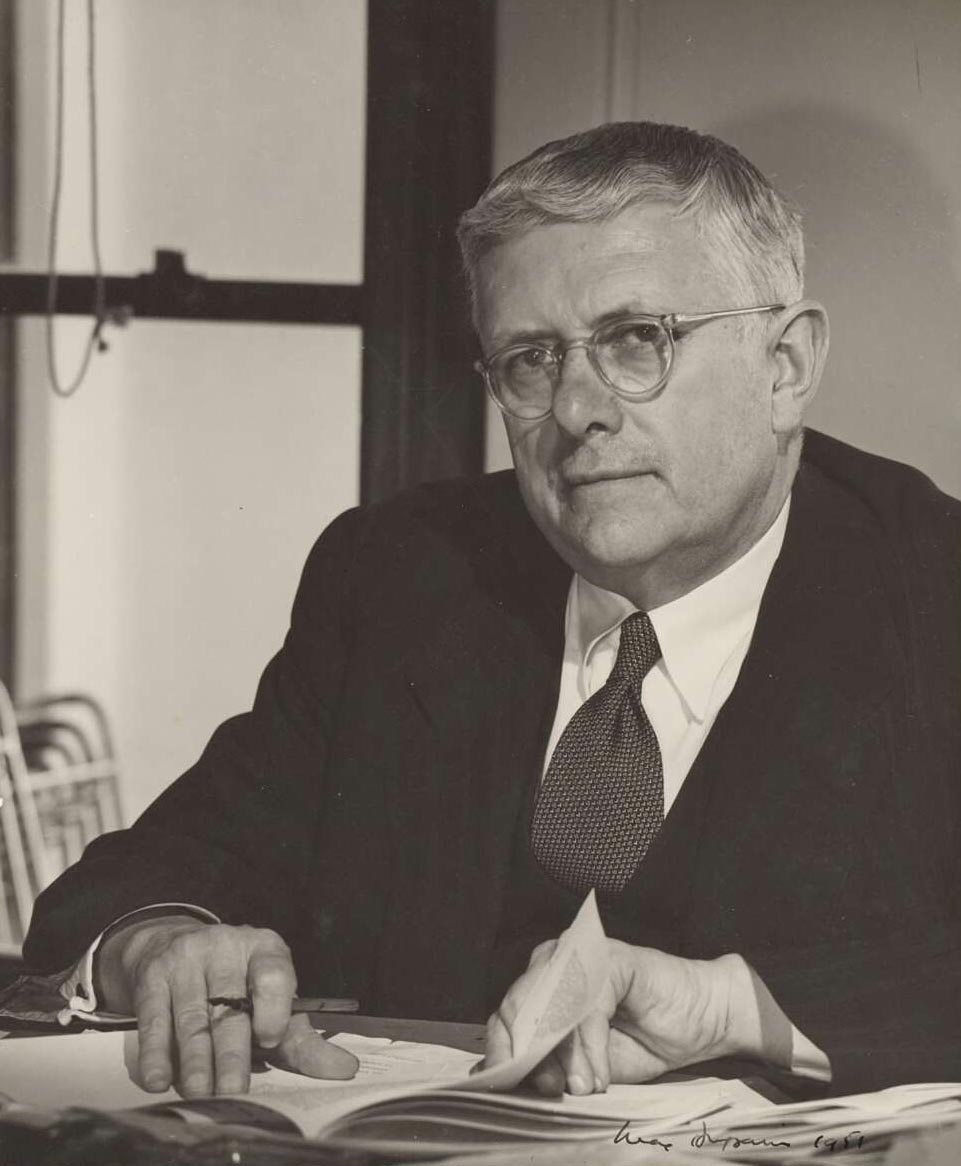

'Doc' Evatt, Minister for External Affairs in the Curtin and Chifley governments, was adamant that the new organisation should have more input from smaller countries.

Evatt succeeded in enlarging the scope of the UN’s main body – the General Assembly, of which he was president from 1948 to 1949.

From the Declaration of St James’s Palace, 12 June 1941:

The only true basis of enduring peace is the willing cooperation of free peoples in a world in which, relieved of the menace of aggression, all may enjoy economic and social security … It is our intention to work together, and with other free peoples, both in war and peace, to this end.

Origins

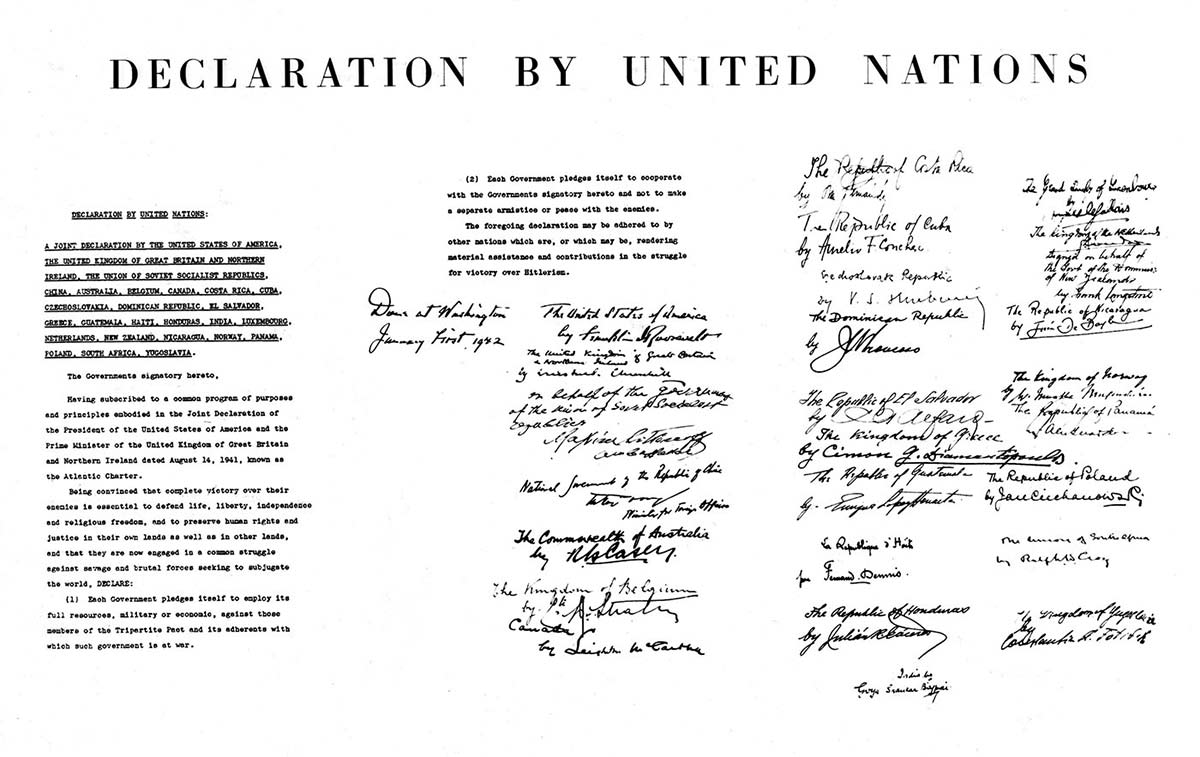

The development of the UN began with the declaration of St James’s Palace in 1941. The Second World War was at its lowest ebb for the Allies, and the declaration was a statement of hope that peace could be achieved for current and future generations.

It was signed by representatives of Great Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and of the exiled governments of Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Yugoslavia and France.

A series of conferences then took place. At each one, more detail and structure was added to the proposals for a replacement organisation for the League of Nations.

In October 1944 China, Great Britain, the Soviet Union and the United States met at the Dumbarton Oaks conference in Washington DC, by which point an organisational structure and procedures had been drafted.

Role of ‘Doc’ Evatt

Herbert Vere Evatt became Minister for External Affairs in 1941, when John Curtin’s wartime Labor government came to power.

Having displayed relatively little interest in foreign policy up to this point, Evatt quickly overcame his lack of experience and went on to take a prominent role in the founding and early running of the United Nations.

In light of the threat posed by Japan’s entry to the war, and the subsequent discovery that Britain and the United States had privately agreed on a ‘Beat Hitler first’ policy, Evatt’s early activity was focused on improving Australia’s fighting position in relation to the rapidly approaching Japanese forces.

When he discovered that Roosevelt and Churchill had agreed with China on peace terms for the Pacific without consulting Australia, he was furious.

He set about formulating an alliance with New Zealand that would form the basis for post-war regional security. Rejection of this by the US bolstered Evatt’s support for a new international organisation being put forward by Britain, America and Russia.

Evatt threw his support behind the new attempts to build the UN. In supporting the idea of collective security, there was at least the possibility that smaller countries like Australia could achieve a better say in international negotiations. It also gave more likelihood of protection for smaller countries against aggression.

Dumbarton Oaks and beyond

However, the central proposal that came out of the 1944 Dumbarton Oaks conference concerned Evatt. In his view it concentrated power in the hands of too few and was therefore not very democratic. There was little or no role for small countries to play. Evatt thought that this would discourage smaller nations from wanting to be involved.

When the San Francisco conference took place in 1945, the Australian delegation put forward a range of amendments to the Dumbarton Oaks proposal and their reasons for them. With the support of other smaller nations, Evatt succeeded in enlarging the scope of the General Assembly so that its powers were closer to those of the Security Council.

His second major achievement was a greater acknowledgement of social and economic roles for the new organisation. Member nations pledged to work towards freedom for all, respect for human rights, full employment and better living standards for all people.

He was unsuccessful in his attempts to reduce the veto power of the Security Council. While amendments were put forward, Russia in particular refused to give ground.

According to the Australian Dictionary of Biography:

Evatt argued that, in the U.N., Australia should not align itself automatically with any major power bloc, but should judge questions on their merits. By enabling the U.N. to develop in its early years as a forum whose outcomes were not always predictable, Evatt's Australia may have helped to secure legitimacy for the new organization, and perhaps allowed the U.N. to act as a force for restraint in the Cold War.

Evatt went on to become the President of the UN General Assembly from 1948 to 1949. During his tenure he was instrumental in the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and prominent in the creation of Israel.

Because of the passion Evatt displayed at the San Francisco conference, the General Assembly voted for Australia to have a non-permanent seat on the Security Council in 1946–47. Australia has subsequently been a member of the UN Security Council on four occasions: 1956–57, 1973–74, 1985–86 and 2013–14.

Explore Defining Moments

References

Doc Evatt, Australian Dictionary of Biography

United Nations Association of Australia

James Cotton and David Lee (eds), Australia and the United Nations, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Canberra, 2012.