At 11am on 11 November 1918 the Armistice ending the First World War came into effect. After four years of fighting, Germany and its allies were defeated. Tens of millions of people had been killed or maimed.

Two months later, delegates of the Western Allies convened in Paris to determine the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, the effects of which are still being felt today.

Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes fought hard to ensure Australian interests were well served.

The Argus on Hughes’ return to Melbourne from Europe, 2 September 1919:

Looking down Collins Street, one saw a huge swaying mass of men and women. There were no barricades … only a single motor car with a little man perched on high, supported by a dozen enthusiastic ‘diggers’, and waving his hand to the mighty crowd that surged around him. And what a crowd! It swept up Collins Street like a great tide; it filled the whole width from doorway to doorway. And all the time it cheered itself hoarse for the sake of the little man in the motor car. It was a great tribute to a man who had done great things.

Armistice

In September 1918 Kaiser Wilhelm II was advised by his generals that the war could not be won and that Germany should sue for peace. The First World War was a grinding battle of attrition and by 1918 Germany was running out of men faster than its enemies.

The United States had entered the war the previous year, reinforcing the Allied armies with about two million men. By November 1918 most of Germany’s allies had surrendered and there were mutinies and mass desertions throughout the army and navy.

On 9 November 1918 the Kaiser abdicated. Representatives of a fledgling German democratic government then agreed to meet the Allied Commander-in-Chief, Marshal Ferdinand Foch, to discuss an armistice.

The German delegation crossed the front line and was escorted to a lone railway carriage – detached from Foch’s personal train – in a clearing in the Compiègne forest north-east of Paris. There they were met by Foch, his chief of staff and two British delegates.

The Germans had arrived hoping to discuss terms. But Foch was in no mood to negotiate. The Germans were forced to sign the Armistice document that was in effect an unconditional surrender.

This took place around 5am on 11 November – what is now Remembrance Day. It came into effect at 11am.

Paris Peace Conference

The war was over but the human and financial costs were high. France and Belgium, where much of the fighting had taken place, had paid an especially high price and unsurprisingly, wanted retribution.

The exact terms of the peace were formulated at the Paris Peace Conference, which took place from 18 January to 28 June 1919.

The conference culminated in the signing of the treaties of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Neuilly-sur-Seine, Trianon, Sèvres and Versailles, which applied to Austria, Bulgaria, Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Germany respectively. Of these, the most important was the Treaty of Versailles because of its impact on the long-term stability of Europe.

Representatives of 32 countries attended. Every nation had its own agenda. Britain and France were determined to get Germany to pay punitive reparations.

Smaller countries wanted independence from colonial rule, while US President Woodrow Wilson wanted to create a new world order based on self-determination, overseen by a new intergovernmental organisation, the League of Nations.

Proceedings were dominated by the so-called Council of Four: Britain (which represented its Empire and dominions, including Australia), the United States, France and Italy. Commissions were set up to report on issues such as reparations and prisoners of war.

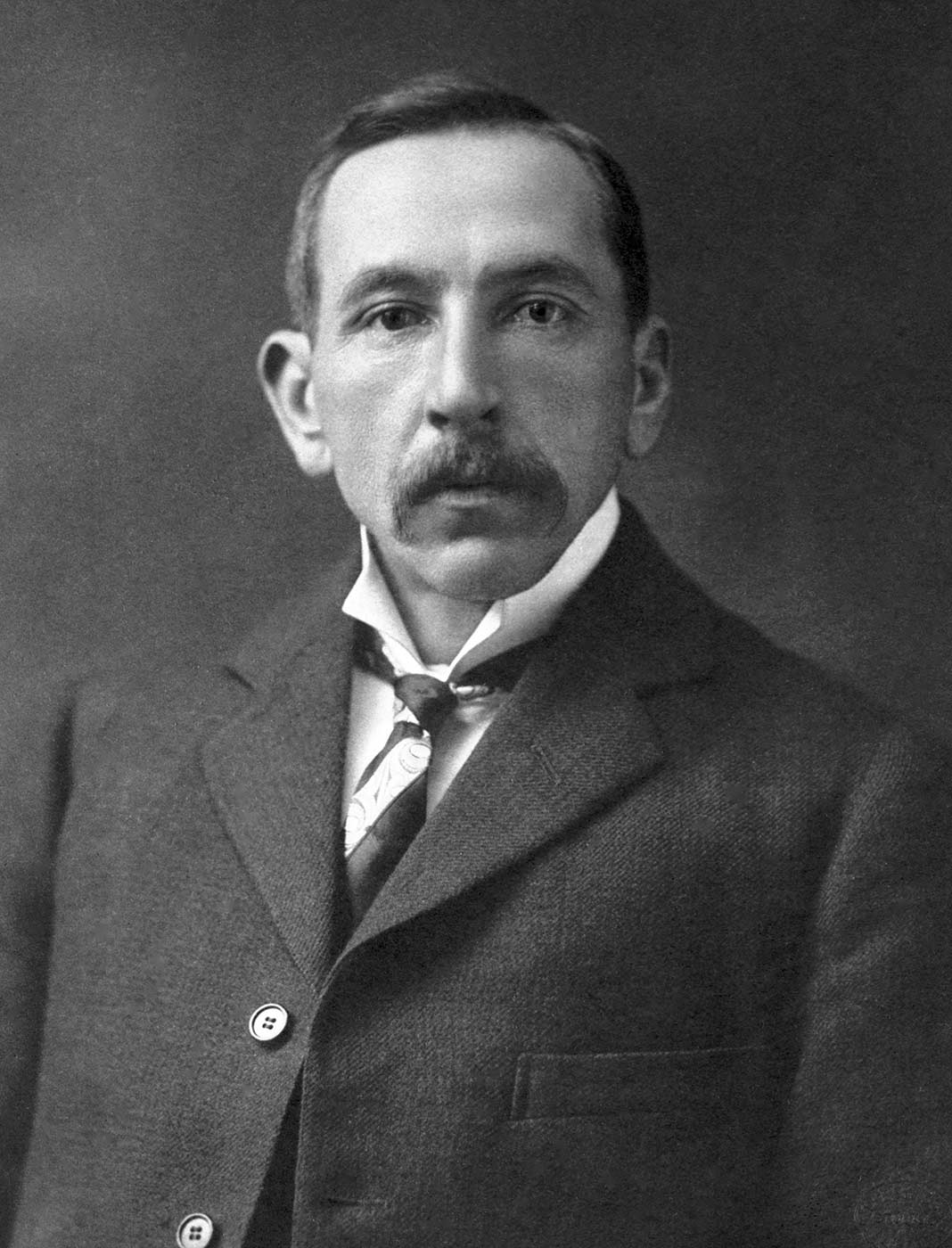

Prime Minister Billy Hughes

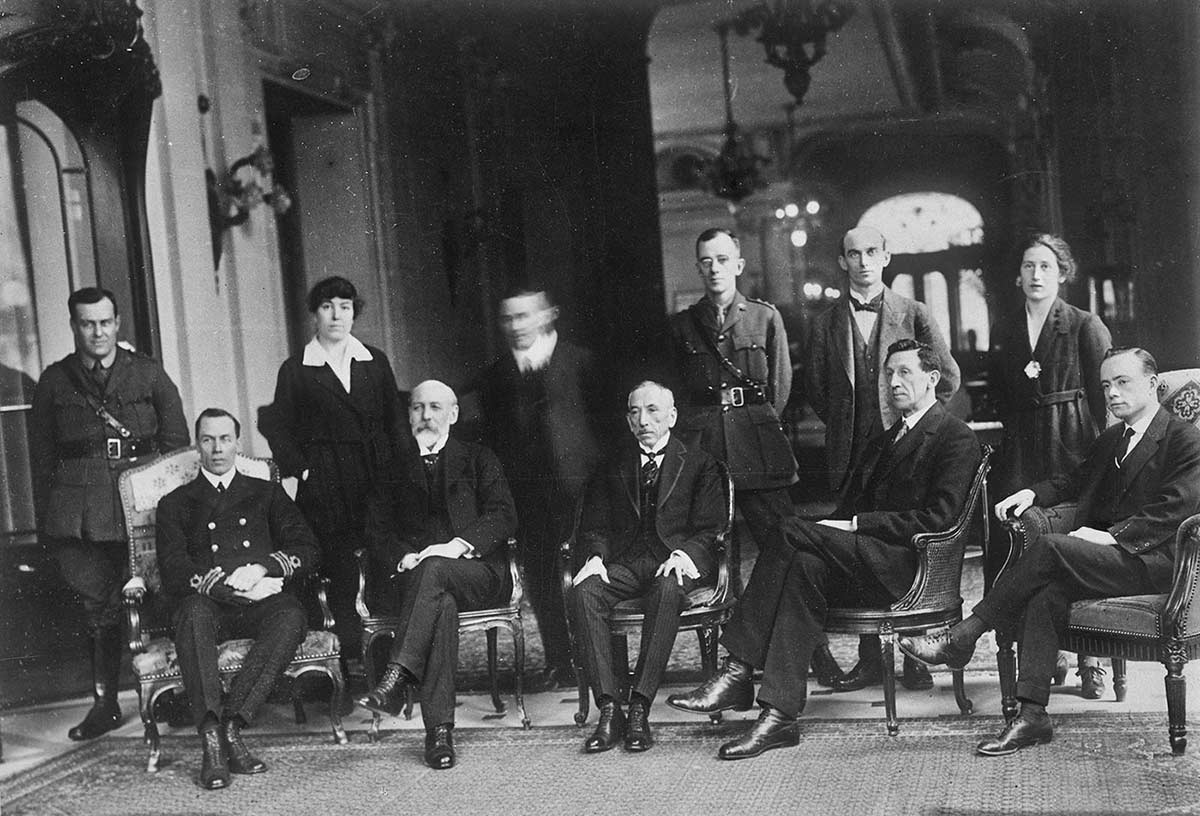

Leading Australia’s delegation to the Conference was Prime Minister Billy Hughes, a staunch advocate of the British Empire and conscription but a wily and determined politician who was willing to fight for Australian interests.

More than 60,000 Australians were killed during the war. By 1920 about 90,000 Australian ex-servicemen were living with a permanent disability.

This was a disproportionately high number of casualties for Australia’s population. Australia’s 60,000 official war dead represented 1.2 per cent of Australia’s people compared to America’s 117,000 casualties (0.1 per cent of its population).

Hughes felt this earned Australia the right to make a series of demands, which brought him into conflict with Wilson in particular, who at one point referred to Hughes as a ‘pestiferous varmint’. Hughes was concerned with three main issues:

- annexing the former German colony of New Guinea

- preventing the introduction of a racial equality clause in the League of Nations Covenant

- getting Australia’s ‘fair’ share of reparations.

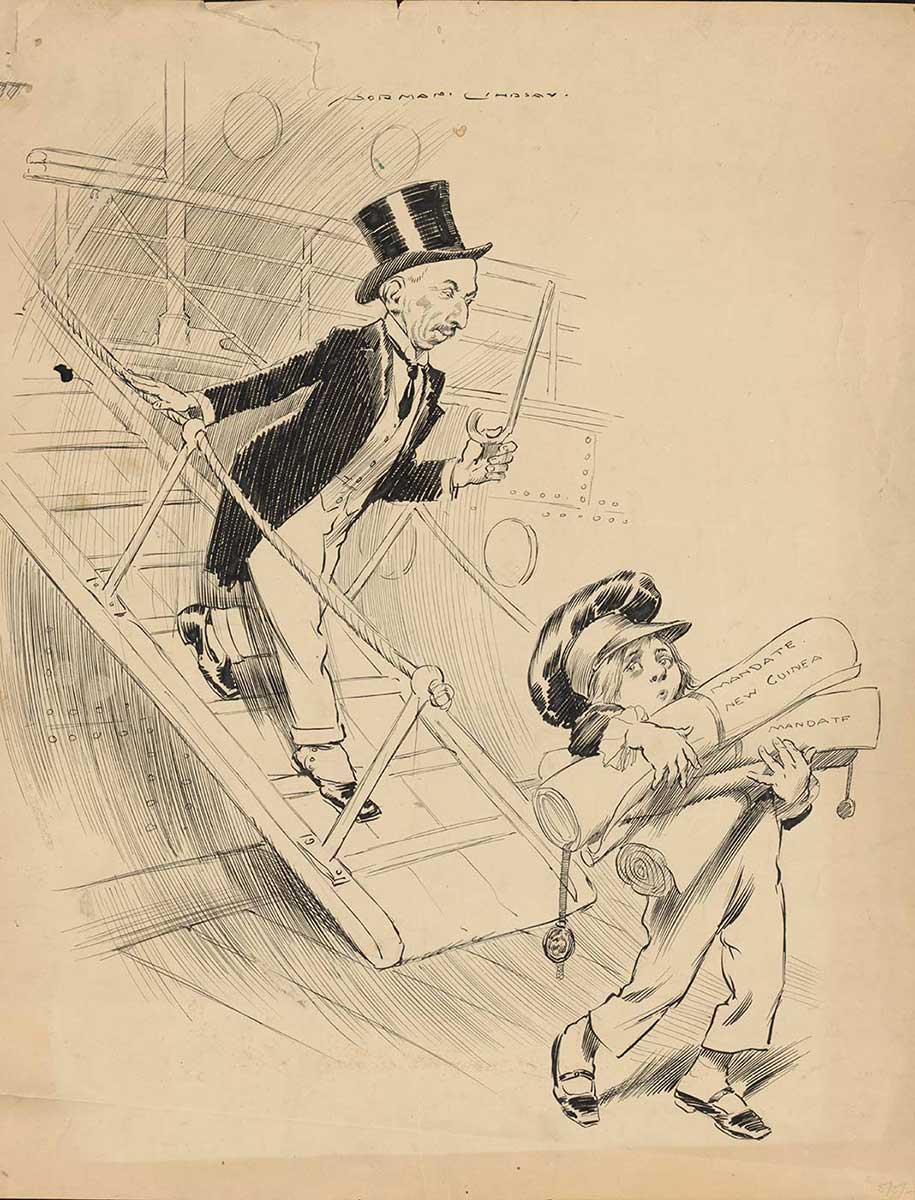

New Guinea

In the opening days of the war Australia had taken control of German New Guinea – the north-eastern part of New Guinea and the nearby Bismarck Archipelago. Hughes argued that it should become an Australian territory as it provided a bulwark against possible Asian invasion.

Wilson, however, felt that such territories should not be annexed but instead held in trust as mandates until they could become independent. His stance was influenced by Japan’s claims to the Caroline and Marshall islands, which being located near Hawaii posed a potential strategic threat.

A solution was found by the British delegation which proposed a new kind of mandate known as the C-class. This prevented the responsible nation from fortifying the mandated territory but allowed them to control immigration. Eventually, Hughes agreed to this.

Racial equality and the White Australia policy

Just as the Versailles Treaty was being drafted, so was the League of Nations Covenant, which provided the framework for the establishment of the league two years later.

The league was established to maintain world peace. Despite some early successes it failed to prevent the outbreak of the Second World War. It did, however, serve as a precursor to the United Nations.

The Japanese delegation advocated that the Covenant contain a racial equality clause.

Hughes was concerned the clause might be used to mount a legal challenge to the White Australia policy, which he considered to be ‘the corner stone of the national edifice’.

Along with his New Zealand and South African counterparts, Hughes exerted pressure on the British who decided to reject the proposal.

Reparations and Nauru

Hughes was less successful when it came to reparations. As a deputy chairman of the reparations committee, Hughes argued that Germany should fully repay the war costs of the Allied nations.

The US did not agree, arguing that only Belgium should be fully compensated. Britain’s Lloyd George also objected because full reparations would destroy the German economy, which would itself affect that of Britain.

Hughes was not interested in how Germany would pay, only that it should. This time, the other dominions did not support him and the Council of Four resolved to distribute reparations on a ratio of 3:2:1 to France, the British Empire and Belgium respectively.

The war cost Australia about £300 million. By 1931, when reparations ceased, Australia had received £5,571,720.

Having missed out on meaningful reparations, Hughes turned his attention to Nauru whose millions of tons of guano (bird droppings) was meeting most of Australia’s need for phosphate – an effective fertiliser. Hughes wanted Nauru to become an Australian mandate and was prepared to refuse to sign the Versailles Treaty if he did not get his way.

Hughes' Cabinet did not support him, and the Council of Four gave the island to Britain. Australia was able to join Britain and New Zealand in buying out the company responsible for mining the phosphate, and over the next 50 years exploited the guano at great profit.

Signing the treaty

The treaty was signed in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles on 28 June 1919. Hughes signed it on behalf of Australia as a member of the British Empire.

The treaty drastically reduced Germany’s armed forces, demilitarised the Rhineland, carved off large areas of German territory and imposed massive reparations. It also contained a ‘war guilt’ clause, effectively blaming Germany for starting the war.

The German delegation had no choice but to sign it. The alternative was to have their country invaded by the Allied armies.

Aftermath and significance of the Versailles Treaty

Hughes had extracted many concessions from the conference and returned to Australia a hero, though he progressively lost control over his government. He resigned as Prime Minister on 9 February 1923.

In the 1930s the war guilt clause and reparations were used by the Nazis as propaganda, blaming Germany’s economic woes – largely caused by the Depression and government mismanagement – on the treaty and the countries responsible for making Germany sign it.

On 22 June 1940 Adolf Hitler accepted France’s surrender in the same train carriage in which the German delegation had surrendered to Foch a generation earlier.

The Treaty of Sèvres also carved up the defeated Ottoman Empire for the benefit of the Allies. These new borders became the cause of many of the tensions that exist in the Middle East today.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

The peace classroom resources, Parliamentary Education Office

The impact of the Versailles Treaty, ABC Radio National

Carl Bridge, William Hughes, Haus Publishing, London, 2011.

Malcolm Brown, 1918 – Year of Victory, Sidgwick & Jackson / Imperial War Museum, London, 1998.

Thomas Keneally, Australians – Eureka to the Diggers, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2011.