Champion Australian Rules footballer Adam Goodes took a strong stand against racism, which led to him being racially abused at matches on a regular basis.

In June 2019 the Australian Football League (AFL) and its 18 clubs apologised unreservedly to Goodes for failing to support him adequately in the face of this abuse.

Adam Goodes, May 2013:

I felt like I was in high school again, being bullied, being called all these names because of my appearance. I didn’t stand up for myself in high school – I’m a lot more confident, I’m a lot more proud about who I am, and my culture, and I decided to stand up last night, and I’ll continue to stand up.

Racism in Australian football

Champion Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander footballers have routinely suffered racist abuse at the hands of AFL supporters. For some, such as Robert Muir and Jim Krakouer, the effect was to curtail their careers.

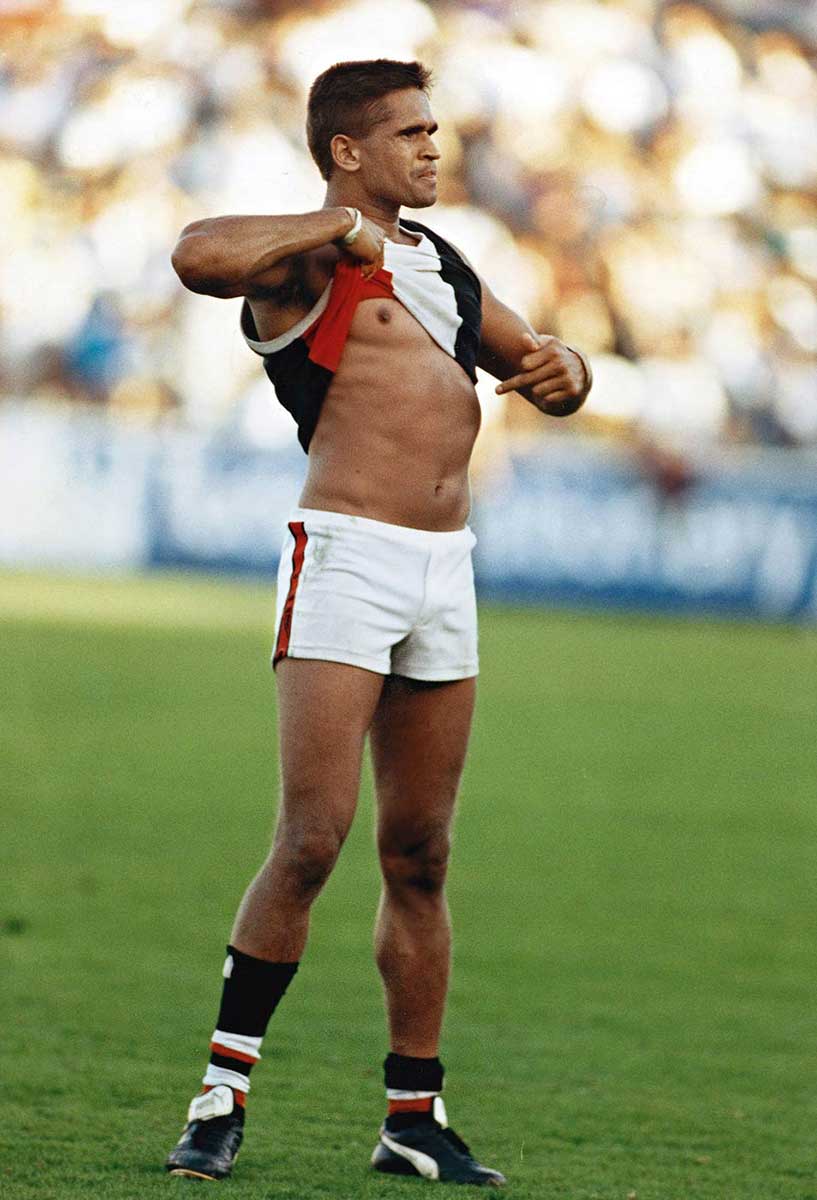

In 1993 at Victoria Park St Kilda star Neil ‘Nicky’ Winmar famously responded to racist abuse from the Collingwood crowd by lifting his shirt after the game and pointing with pride to his dark skin.

Many supported Winmar, but others, including players, argued that abusing players to unsettle them was part of the game. Collingwood president Allan McAlister even commented:

as long as they [Aboriginal players] conduct themselves like white people, well, off the field, everyone will admire and respect them … As long as they conduct themselves like human beings, they will be all right. That’s the key.

Gilbert McAdams, Winmar’s teammate, responded to the racism, saying:

… that Vic Park day is where you drew the line in the sand and that's where it all changed. A lot of good came out of that because it did make a lot of people stand up and take notice and probably get a better understanding of Aboriginal Australia and how we feel and the things that we had to put up with to play the game. A lot of stuff back then was hush-hush, so for it to come out was massive. It opened a lot of clubs' eyes, and not only clubs but supporters.

In 1995, following a campaign initiated by Essendon’s Michael Long, the AFL added a new rule. Rule 30 banned players from using racial or religious abuse against each other. The AFL engaged with Indigenous communities and eventually instituted an annual ‘Indigenous round’.

Adam Goodes

Adam Goodes, born in 1980, played for the Sydney Swans for his entire first grade AFL career, from 1999 to 2015.

He won two premierships with Sydney (2005 and 2012), and twice won the game’s highest individual honour, the Brownlow Medal (2003 and 2006). Tough and competitive, he was also a supremely skilful player.

Goodes’ Aboriginality is important to him. He was brought up in South Australia and Victoria by his Adnyamathanha and Narungga mother, Lisa May, herself a member of the Stolen Generations.

Lisa, along with eight siblings, had been taken from her family when she was five, and never saw her parents again. Goodes has said of his mother:

Mum’s had the biggest influence on my life. I’ve been very lucky to grow up with not only my mum, but my aunties, too. I’ve always had lots of care from different women. That’s why I have a lot of empathy to want to support and help people.

The Collingwood incident

In May 2013, in the first match of the Indigenous round, the Swans were playing Collingwood. Near the end of the game, with the Swans ahead, a 13-year-old girl and Collingwood supporter yelled at Goodes, calling him an ‘ape’.

Goodes summoned security officers, who ejected the girl from the ground. Collingwood officials apologised to Goodes immediately after the game. The AFL supported him.

But conservative commentators attacked Goodes for taking, in Andrew Bolt’s words, ‘outsized offence at the rudeness of a girl’. He was regularly booed at games from then on.

The girl rang Goodes to apologise. Goodes commented publicly that, while being called ‘monkey’ or ‘ape’ – not for the first time – was ‘shattering’, he did not blame the girl herself:

It’s what she hears, in the environment she’s grown up in, that has made her think that it is OK.

Australian of the Year

In January 2014 Goodes was chosen as Australian of the Year, with Prime Minister Tony Abbott commenting that he stood ‘for decency in national life’.

Goodes took the opportunity to speak out against racism in Australia. Indeed, he felt it was his duty to use his public position to achieve change. He later commented, ‘If people only remember me for my football, I’ve failed in life.’

Goodes is by no means at the radical end of Aboriginal politics, and his Australian of the Year acceptance speech was markedly conciliatory. Yet many members of the public felt attacked, and passions were enflamed.

One former A-League soccer player went so far as to tweet that Goodes should be deported (where to was not clear). Fans continued to boo him.

The war cry dance

Goodes was engaging more with his ancestral culture. Long before the AFL accepted the idea, he had believed that Australian football may have been influenced by Aboriginal games such as marngrook, played by the Kulin people (especially Djabwurrung and Woiwurrung) around Melbourne.

In May 2015, in the Swans’ Indigenous round game against Carlton at the SCG, Goodes took this further and performed what was described as an Aboriginal war cry dance as a goal celebration. He concluded by miming throwing a spear at the Carlton supporters.

Goodes’ dance was much less aggressive than the Maori haka regularly performed by the All Blacks before games. He also pointed out that an expression of Aboriginal heritage was appropriate in the Indigenous round.

By his own account, players on both sides ‘loved it’, and the response he hoped to get from the Carlton supporters was ‘Yep, we see you, and we acknowledge you – bring it on’.

Yet much of the public reacted vitriolically. Some historians have suggested that non-Indigenous Australians were ready to accept equality as a goal, but only a one-sided equality which rejected the intrusion of Aboriginal cultural practices into the non-Indigenous arena.

Goodes retires and the AFL apologises

Following the war dance incident, fans booed Goodes at every match with renewed intensity. The AFL clubs made efforts to discourage this hostile behaviour and many fans and public figures spoke in support of Goodes.

Nevertheless, the booing continued. By the end of the season Goodes had retired from the game.

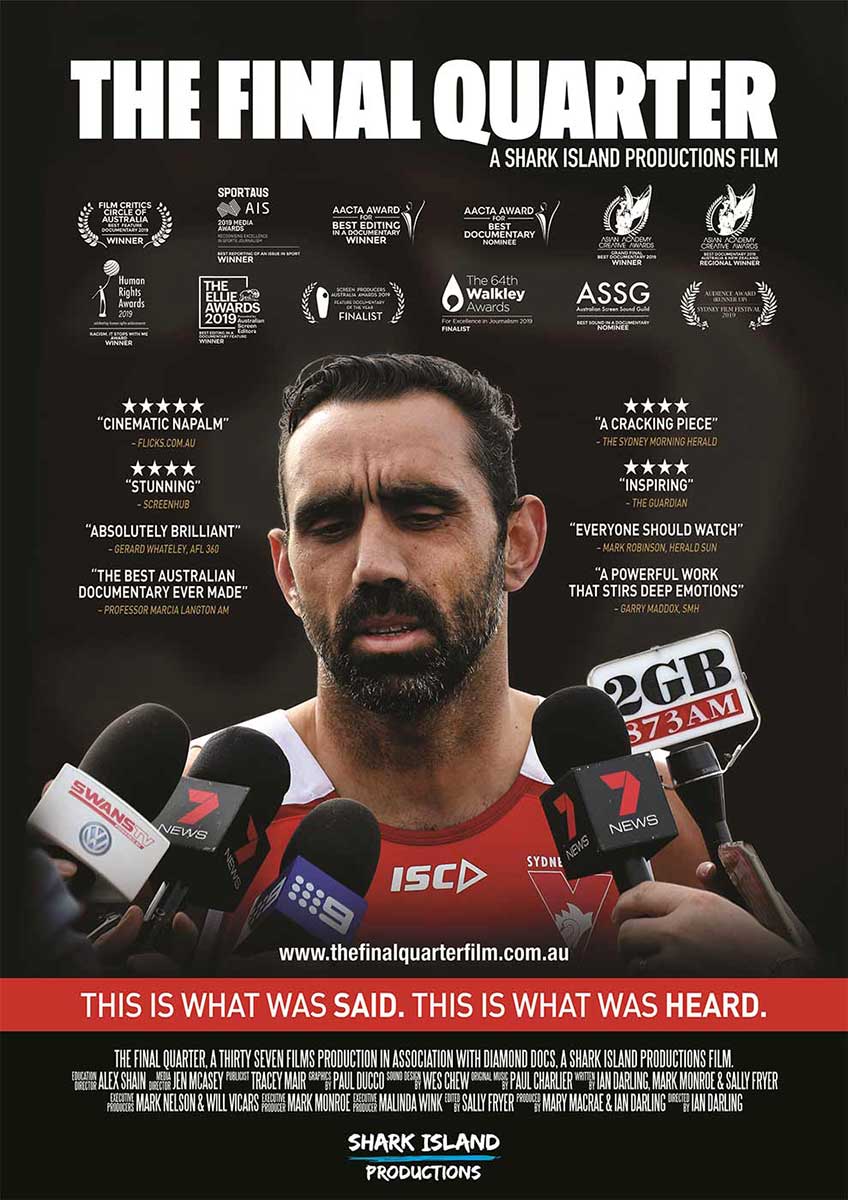

Four years later, in 2019, two documentaries, The Final Quarter and The Australian Dream, were released. Both dealt with the final stages of Goodes’ career and the treatment he had received.

On 7 June 2019, the day The Final Quarter was to premiere at the Sydney Film Festival, the AFL and its 18 clubs made a formal apology to Goodes for the game’s failure to stand up for him and ‘call out’ the treatment he was receiving.

The apology concluded, ‘We never want to see the mistakes of the past repeated.’

Goodes acknowledged the apology, but did not return to Australian football, preferring to play amateur soccer (his ‘first love’) and basketball (in a team with former Swans players).

Since retiring he has devoted himself to a wide range of Indigenous organisations.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

Education resources for The Final Quarter film, Shark Island Productions

Glenn D’Cruz, ‘Breaking bad: The booing of Adam Goodes and the politics of the black sports celebrity in Australia’, Celebrity Studies 9:1, 2018, pp. 131–138.

Barry Judd and Tim Butcher, ‘Beyond equality: The place of Aboriginal culture in the Australian game of football’, Australian Aboriginal Studies, vol. 2016/1, pp. 68–84.

Donald McRae, ‘Adam Goodes: 'Instead of masking racism, we need to deal with it day-to-day’, The Guardian, 3 March 2020.

J. Weston (ed.), The Australian Game of Football since 1858, Geoff Slattery Publishing, 2008.