The 1915 amendments to the Aborigines Protection Act 1909 gave the New South Wales (NSW) Aborigines Protection Board the power to remove any Indigenous child at any time and for any reason.

The phrasing of one amendment was so broad as to enable any interpretation by the Board’s inspectors, and led to thousands of Indigenous children being taken from their parents on the basis of race alone.

This government-sanctioned practice was widespread across Australia, and created tens of thousands of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander members of what are now known as the Stolen Generations.

Section 13A, Aborigines Protection Amending Act, No.2 of 1915:

The Board may assume full control and custody of the child of any aborigine, if after due inquiry it is satisfied that such a course is in the interest of the moral and physical welfare of such child. The Board may thereupon remove such child to such control and care as it thinks best.

Establishing the Board

The Board for the Protection of Aborigines was established by the NSW Government on 2 June 1883. As described by then Premier Alex Stuart in a Cabinet minute, the Board was to fulfil:

the duty of the State to assist in any effort which is being made for the elevation of the race, by affording rudimentary instruction, and by aiding in the cost of maintenance or clothing where necessary, as well as by grants of land, gifts of boats, or implements of industrial work.i

The Board operated without legislative authority until 1909.

Initially, its activity was limited to those areas identified by the Premier, such as issuing rations (though the amounts issued were less than those issued to whites), clothing and blankets, and the creation of reserves for Indigenous people. It also purchased boats and fishing equipment for coastal Aboriginal people, and occasionally seed and farming equipment for those who lived on inland reserves.

The Board was keen to support the creation of reserves, especially if there was the potential for agricultural production, which they saw as a civilising activity.

Seeking greater control

Growing increasingly ambitious, the Board began to seek greater control over the lives of Indigenous people. It achieved this with the 1909 Act, which provided for all reserves and stations and all buildings to be vested in the Board.

The Board had the power to: move Aboriginal people out of towns; set up managers, local committees and local guardians (police) for the reserves; control reserves; prevent liquor being sold to Aboriginals; and to stop whites from associating with Aboriginals or entering the reserves. It even retained ownership of the blankets it distributed.

The Board had sought the power to remove children, but the 1909 Act only gave it the same powers that applied to neglected white children. The 1915 amendments gave it the power to remove any child at any time and for any reason.

The rationale for the forced removal of Aboriginal children from their parents was part of a broader policy framework known as assimilation.

Non-Indigenous Australians had convinced themselves that Aboriginal people were a ‘dying race’, and that those remaining, especially those of mixed parentage, would be better off assimilated into ‘white’ society.

Babies were sent to the United Aborigines Mission Home in Bomaderry; girls were sent to the Cootamundra Girls Home and boys to Kinchela Aboriginal Boys Training Home near Kempsey.

While the Board asserted that children received care and education at these institutions, oral histories from the children themselves show the homes to be harsh and desolate places, offering a limited future. The children were brought up to reject their Aboriginal heritage.

Many other children were sent to institutions, which received both ‘white’ and Aboriginal children. In such institutions, retention of Aboriginal identity was even more difficult and many children would have grown up unaware of their Aboriginal heritage.

Abuse of these children was widespread and commonplace.

Many children were fostered or adopted by white families, where most lost all connection to their Aboriginal identity and heritage and were even less likely to remain with their siblings.

Disastrous impact

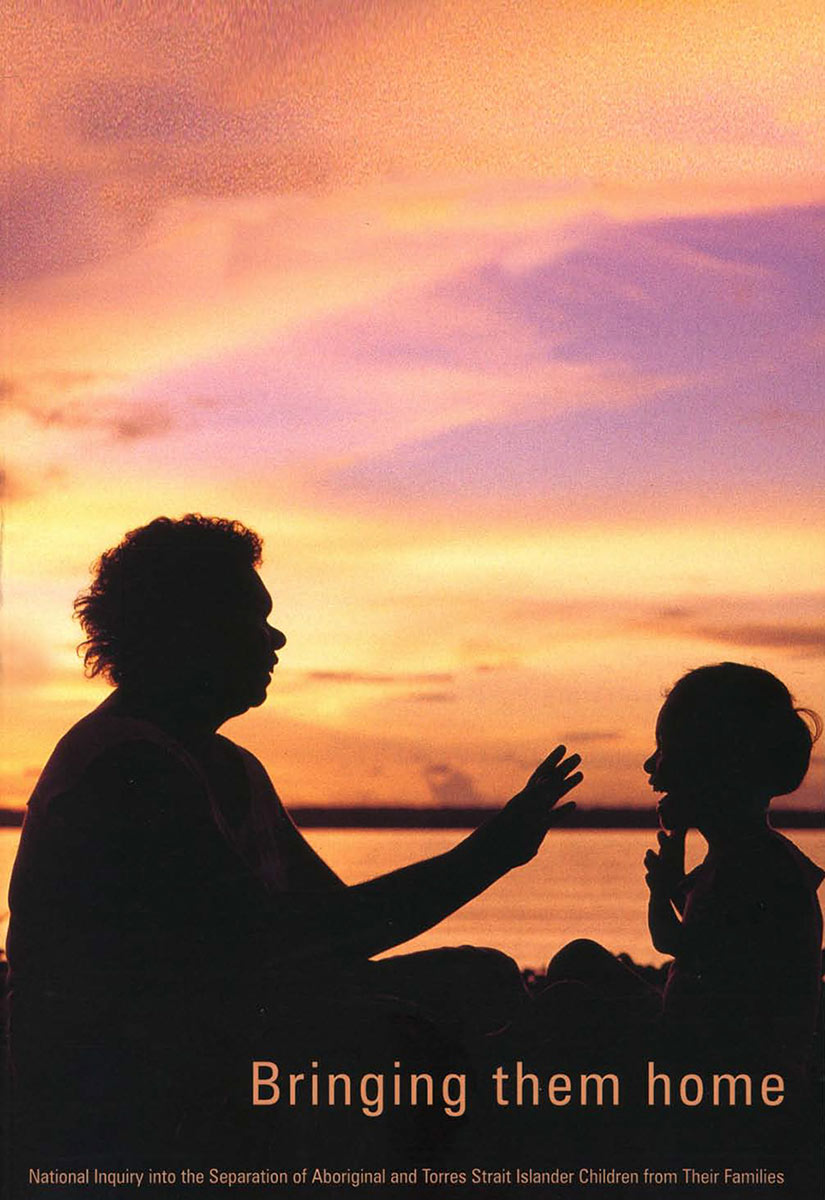

The Act had a disastrous impact on Aboriginal families and culture. The 1997 Bringing Them Home report found that children removed from their families were disadvantaged in the following ways:

- They were more likely to come to the attention of the police as they grew into adolescence

- They were more likely to suffer low self-esteem, depression and other mental illnesses

- They were more vulnerable to physical, emotional and sexual abuse while in ‘care’

- They had been almost always taught to reject their Aboriginality and Aboriginal culture

- They were unable to retain links with their land

- They could not take a role in the cultural and spiritual life of their former communities

- They were unlikely to be able to establish their right to native title.ii

Because of poor record keeping, no one knows the precise number of children forcibly removed under the Act, or under other similar legislation deployed around the country. Estimates vary.

Peter Read, who has carried out extensive research on the removal of Indigenous children in Australia, has suggested a figure of up to 50,000 people 'would not be unreasonable'.

The Bringing Them Home report suggests a maximum figure of one in three Indigenous children were removed and a minimum of one in 10, and stated that no Indigenous family is untouched by forced separation.iii

The lack of accurate records (some of which were deliberately destroyed or not created in the first place) also prevents many family members wishing to be reunited from finding each other.

One of the main recommendations from the Bringing Them Home report was for the government to make a national apology to the Stolen Generations. This finally took place on 13 February 2008 and is another featured moment.

The Aborigines Protection Act was finally repealed in 1969 but the legacy of the legislation and that of other states endures among the thousands of Stolen Generations in Australia. Many remain deeply traumatised by their experience as children. Because this trauma can be trans-generational, these policies continue to affect the Aboriginal and Torres Strait community today.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

Bringing Them Home, Australian Human Rights Commission

The Stolen Generations factsheet, RacismNoWay

To remove and protect, AIATSIS

Anna Haebich, Broken Circles: Fragmenting Indigenous Families 1800–2000, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, Fremantle, 2000.

Doreen Mellor and Anna Haebich (eds), Many Voices: Reflections on Experiences of Indigenous Child Separation, Doreen Mellor and Anna Haebich (eds), National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2002.