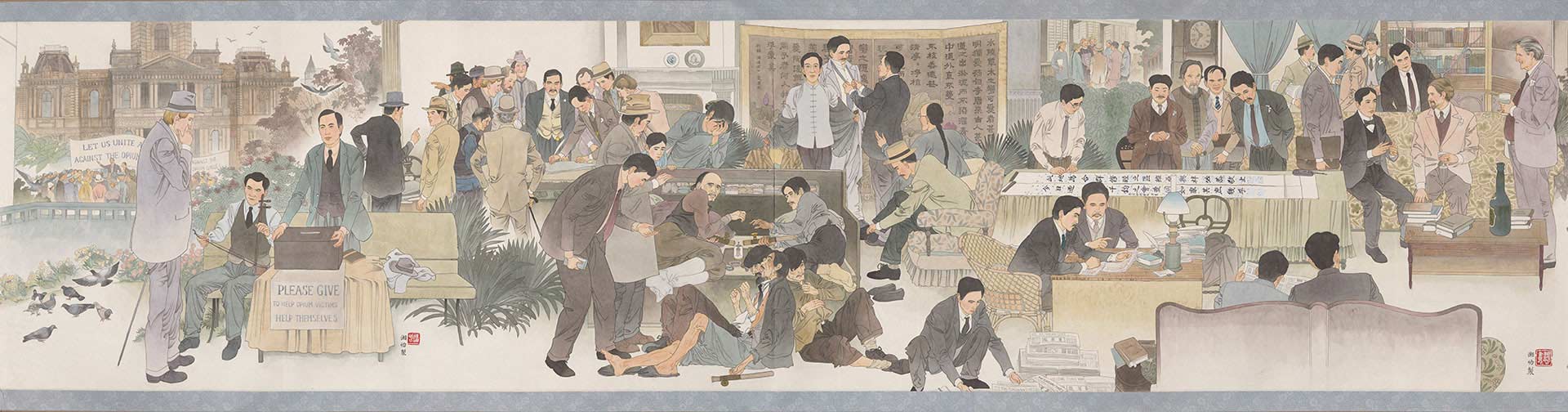

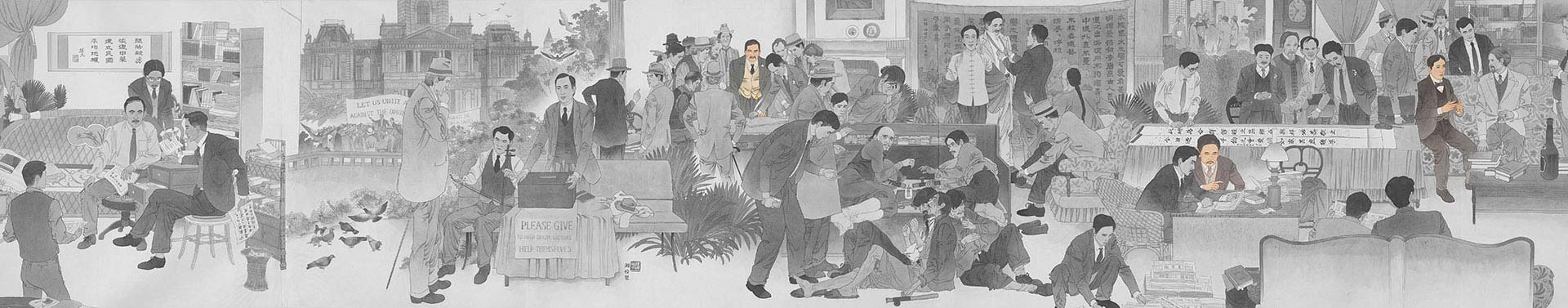

Scene 8 (right to left)

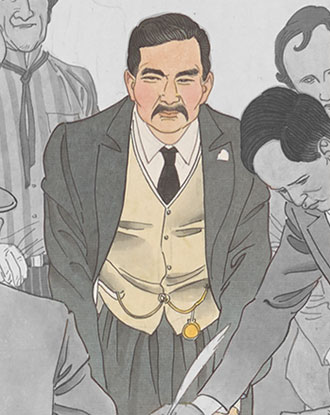

In this scene Chinese monarchists, including Liang Qichao and Ping Nam, and revolutionaries are lobbying Chinese in Australia for their support. The Tung Wah Times, a pro-monarchist paper, is being sorted for distribution. The use of opium was a significant issue in the Chinese community, referenced by the group of opium-smokers with pipes, shown centre. On the far left, notable Sydney merchant Mei Quong Tart is pictured both as a businessman, and delivering a lecture on the evils of opium to a crowd outside Sydney Town Hall.

The influence of the monarchists

After the failure of the One Hundred Days’ Reform in 1898, China split into two main political movements. Kang Youwei led the monarchists who hoped to restore the influence of the reformist Emperor Kuang Hsu, by reducing the power of the Empress Dowager Ci Xi. The Hsing Chung Hui (Society for the Revival of China), a revolutionary movement led by Dr Sun Yat-Sen, were seeking to completely overthrow the Imperial Qing (Manchu) Dynasty.

The influence of the monarchists was the first to reach Australia. In 1899, Kang Yuwei wrote to Australian businessman Mei Quong Tart, seeking support. One result was the formation, in 1900, of the New South Wales Chinese Empire Reform Association, run by Chinese merchants Thomas Yee Hing, Ping Nam, Gilbert Quoy and C Leanfore.

In 1900 Liang Qichao, a leading figure in the monarchist movement, arrived from China and travelled throughout Australia raising support for the Emperor. The Tung Wah Times, a pro-monarchist paper, was used by the Sydney-based monarchists to influence Chinese people throughout Australia and New Zealand.

It was not until 1908 that the influence of the Hsing Chung Hui was felt in Australia. However, reform of the old Chinese ways was widespread, symbolised in particular by the adoption of Western dress. There was even a Queue-Cutting Society whose members cut off their pigtails (queues) to symbolise their rejection of the Empress Dowager.

In 1909 the first Chinese consulate opened in Melbourne. However, although it lobbied for the removal of restrictions on Chinese immigration, there was little response from the Commonwealth Government.

The anti-opium crusade

Many Chinese immigrants brought the habit of opium smoking with them from China. This contributed to the animosity displayed by European miners towards the Chinese on the goldfields.

Opium was not illegal at this time, and from 1871 to 1905 the amount of opium imported into Australia increased fivefold to keep up with consumption.

Many Chinese people in Australia became destitute because of their addiction to opium smoking. Anti-opium societies were formed and Chinese community leaders and Chinese newspapers were actively involved in the anti-opium crusade.

In 1883 Mei Quong Tart delivered a petition with 4000 signatures to the executive council, effectively launching the crusade in New South Wales. Quong Tart gave talks to both Chinese and Anglo-Australians calling for a ban on opium imports.

Notable figures

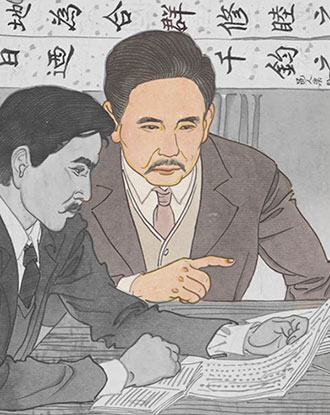

Ling Qichao

A leading Chinese monarchist, Liang Qichao came to Australia in 1900 to raise support for the Guangxu Emperor.

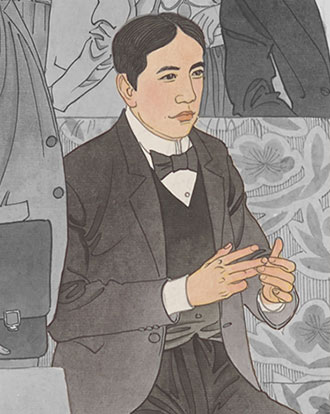

Ping Nam

One of the leaders of the New South Wales Chinese Empire Reform Association, which promoted the Chinese monarchist cause.

Mei Quong Tart

A businessman and leader, respected by both Chinese and European Australian communities, who campaigned strongly against the opium trade.