Manufacture and typology of gorgets

Aboriginal gorgets fall into recognisable typological sets with similarities of shape and design. They were most commonly made from brass or bronze and less often from copper. Silver plate was sometimes used as a finish. Only one known gorget was made from a precious metal and it was the silver gorget made for Jackey Jackey described in the heroic acts section.

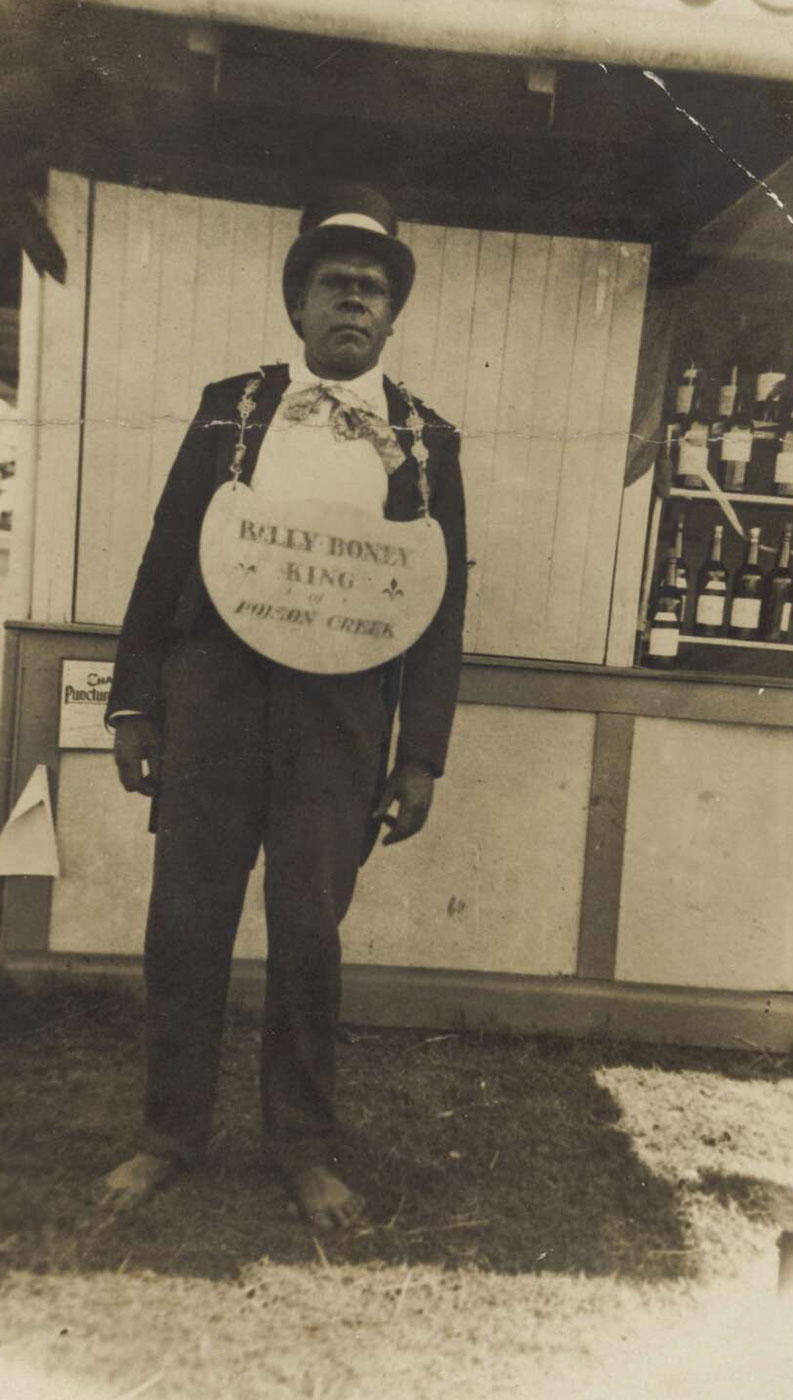

As noted in the introduction, gorgets were usually crescent-shaped and at least twice the size of military gorgets. However, more recent gorgets are unusual shapes and often quite large. The largest gorget found during the research for this book was made for ‘Billy Boney, King of Poison Creek’.

It is only known through a photograph of Billy who stands with the plate covering all of his midriff. The blank shapes of the gorgets were produced either by the simple sawn plate or by sand-casting methods. The process of sand-casting involves the creation of a mould in sand into which the molten metal is poured and allowed to cool and solidify.

Indications of sand-casting are small pits and irregularities on the reverse side of the gorget and the moulded appearance of the final shape. The engraved side of a cast gorget was smoothed and finished to allow for decoration. Sawn shapes were cut from metal plates which had been flattened in a rolling mill. Sawn plates have a smoother surface than those which were sand-cast.

The main point that can be made regarding typological similarities between the gorgets is that most appear to follow an established tradition of shape and design. Some gorgets even appear to be by the same maker and mass-produced for a growing market. On the whole, the manufacture and engraving is simple, although most are decorated with some kind of engraved pictorial scene.

Of the gorgets in the National Museum of Australia’s collection only two have an inscription embellished simply with flourishes and only one has an inscription alone (collection numbers 1985.0336.0001, A-ON 117, 1985.0099.0001).

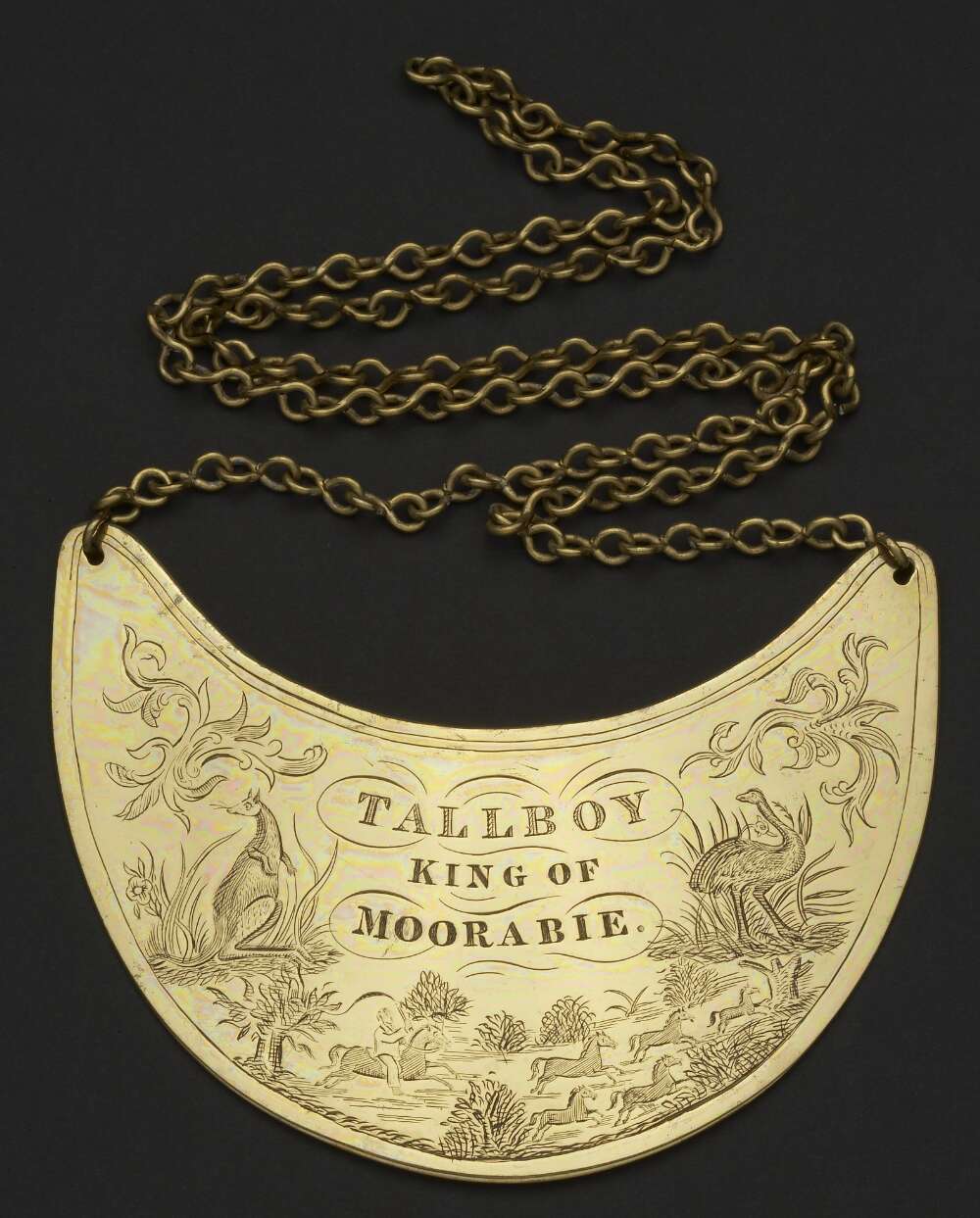

The National Library of Australia holds a small collection of three gorgets among which is one which is a very good example of the finest gorgets. It was made for ‘Tallboy, King of Moorabie’.

In shape and quality it is a close copy of a military gorget and it is decorated with a finely engraved tableau of a rider chasing a herd of horses through the bush with an emu and a kangaroo supporting the inscription. The maker is named on the back: ‘J. Fitzsimys, 113 Pitt Street, Arts, Sydney’.

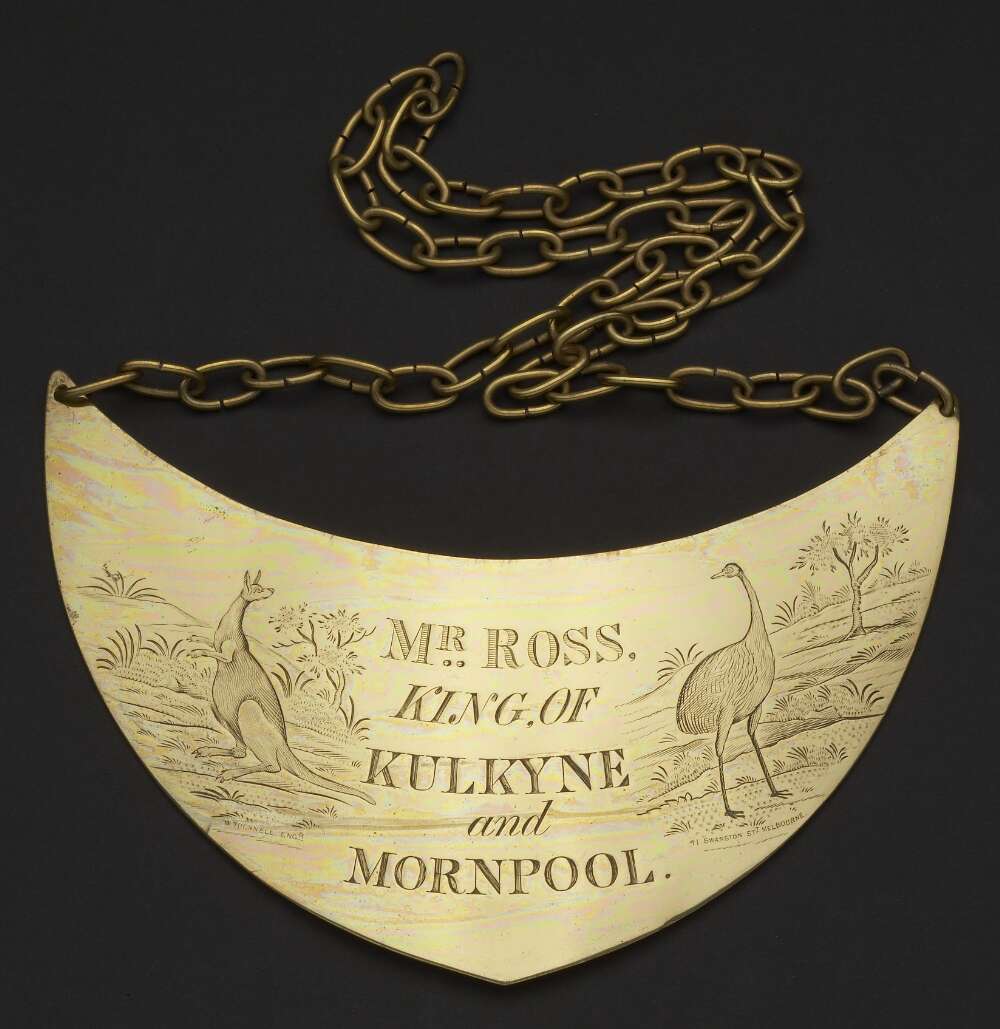

Another of the Library’s gorgets, made for ‘Mr. Ross, King of Kulkyne and Mornpool’, is almost as fine and is suspended on a skilfully handmade chain. Its shape is unusual in that it is peaked at the base giving it a shield-like appearance.

The design and engraving on many of the gorgets are naive, suggesting that they were made by tradespeople rather than fine craftspeople. The quality of lettering used for the inscriptions is also generally simple, employing either a variation on roman, block or copperplate scripts and often poorly spaced.

The blanks were mass-produced by some companies in England and Australia leaving the engraving to the purchaser. It appears from close examination of the National Museum of Australia’s gorgets that some blanks had the same design engraved on the them and that the purchaser then added an inscription.

This conclusion is reached because the same design with the same quality of engraving is apparent on a number of gorgets which have various qualities and styles of inscription. An outstanding example of lettering and design being in completely different styles suggesting the later addition of the inscription is that made for ‘Dick, King of Evesham’ (collection number A-ON 118).

Aboriginal figures and forms

Only eight of the gorgets in the Museum’s collection have designs which indicate Aboriginality by the use of Aboriginal figures and/or artefacts or designs after Aboriginal artforms. The gorget made for Coomee (collection number 1985.0059.0374) is decorated with what appears to be a copy of the decorative or ceremonial scars on her body.

Two gorgets, made for ‘Sawyer, King of Wickham-Hill’ (collection number 1985.0059.0387) and Dick (mentioned above), have very similar designs which depict Aboriginal men both posing with a spear and a boomerang. However, that is where the similarity between the gorgets ends. Dick’s gorget is notable because the man in the design is shown wearing a gorget. People wearing gorgets also appear on gorgets in other collections.

Most human figures engraved on the gorgets show some evidence of contact with colonial society. Very few designs are confined to a wholly Aboriginal subject. One contrary example is the gorget made for ‘U. Robert, King of Big Leather and Big River Tribes’ (collection number 1985.0059.0364) which has a design of Aboriginal weapons. However, the weapons are crossed and arranged in the fashion commonly employed for weapons in European heraldic designs.

Some designs provide evidence for the impact of colonial society on Aboriginal cultural traditions. For example, designs such as those on the gorgets of Jack the Traveller (collection number 1985.0059.0371) and King John Cry (collection number 1985.0059.0380) show Aboriginal men using flintlock guns rather than spears, clubs or boomerangs to hunt their native quarry.

The skill with which Aboriginal people handled guns was often commented on by colonial writers. The Museum’s finest gorget made for ‘Billy Hippie, King of Minnon’ (collection number 1985.0059.0363), is decorated with a beautifully executed design of an Aboriginal stockman riding a fine horse, skilfully jumping a log in a flat-out chase after some wild cattle. He is outfitted as a dandy colonial stockman but is riding barefoot in the style made famous by Aboriginal people. Many colonial commentators wrote about the skill of Aboriginal riders and how they rode barefoot, grasping the stirrup iron between their big toe and the next.

Native bush scenes

Gorgets were frequently decorated with scenes of native bush, for example, those of ‘Thomas Tinboy, King of Nelligan' (collection number 1985.0059.0377), ‘Tommy, King of Gongolgon’ (collection number 1985.0059.0366), ‘Dicky, King of Clyde Road’ (collection number 1985.0059.0375) and ‘Peter, King of Tchanning’ (collection number 1985.0059.0386). The xanthorrhoea is very commonly used in the designs and one is often placed beside the familiar emu and kangaroo.

Surprisingly, the popular and well-known waratah is not so commonly used in the designs on gorgets. Only one of the Museum’s gorgets, the one made for ‘Tommy, King of Gongolgon’, has it as a motif. Small, leafy branches which bear close resemblance to the laurel branches engraved on military gorgets are also a recurring motif in the designs.

Coronets, crowns and sunbursts

Some of the gorgets are ornamented with coronets which is a motif clearly borrowed from military gorgets, for example, the gorgets made for ‘Timothy, Chief of Merricumbene’ (collection number 1985.0059.0378), ‘Charley York, Chief of Bullangamang’ (collection number 1985.0059.0370), ‘Jemmy Muggle, King of Wiggley’ (collection number 1985.0059.0376) and ‘Tommy, Constable, Wellington’ (collection number 1985.0059.0369). However, the royal crown rather than a coronet was usual on military gorgets. The difference between a crown and a coronet is that a crown is only worn by the head of state while a coronet is worn by other noble people.

The crown was used on the military gorgets because the armed forces were in the service of the English head of state. The use of coronets on Aboriginal gorgets suggests an attempt to distinguish the rank of Aboriginal royalty as lower than that of English royalty, placing it on a par with dukes and earls. All the coronets depicted on the gorgets in the Museum’s collection are of the same design and with five points and a central diamond flanked by oval or circular jewels.

Another device borrowed directly from English heraldry and used on the gorgets is the centrally placed sunburst design or ‘escarbuncle’. The escarbuncle with a face in the centre indicates faithfulness.

The device was used on four of the Museum’s gorgets, those made for Tumberilagong (collection number A-ON 115), ‘Neddy, King of Neis Valley’ (collection number 1985.0059.0383), ‘John Neville, King of Mahaderree’ (collection number 1985.0059.0381) and ‘Charley York, Chief of Bullangamang’ (collection number 1985.0059.0370).

The gorgets in the Museum’s collection which are decorated with emu and kangaroo designs are very similar in all ways and date from the early mid to late 19th century. Most of them were sand-cast brass and are a deep crescent shape. They also share the same sketchy emu and kangaroo. The emus look more like flamingos with their heavy hooked beaks and bulbous heads. The emu was first made familiar to the English public in the published journals of Arthur Phillip (1789) and John White (1790).

The engravings in the journals are no closer to the natural bird than those appearing on the gorgets. However, the kangaroos on the gorgets all appear to be copied after a celebrated oil painting done in 1771–72 by the great English animal artist George Stubbs, called ‘the Kangaroo of New South Wales’ (now in the collection at Parham Park, West Sussex, England). Stubbs’ kangaroo was first reproduced in Hawkesworth’s (1773) account of James Cook’s first epic voyage in the ship Endeavour to ‘the Great South Land’, 1768–71.

In June 1770 the Endeavour was damaged on the Great Barrier Reef. Cook took refuge in a nearby coastal river to repair his ship. He named the river Endeavour after his ship. During their short stay in the area, Sydney Parkinson, a scientist and illustrator with the expedition, sketched a kangaroo. His drawings provided the model for Stubbs’ painting.

[1] Hawkesworth’s engraving after Stubbs was often reproduced in popular accounts of the colony and was one of the most famous images of Australia. Therefore it is not surprising that it was the model for the kangaroos on the gorgets. Stubbs’ kangaroo, as are those on most known gorgets, is in the heraldic posture known as ‘regardant’ or looking back over its shoulder.

Typological similarities between the gorgets decorated with the emu and kangaroo in the Museum’s collection provide the most convincing evidence that many gorgets were mass-produced and that there was more than one maker. Both the blanks and engraved decorations on the gorgets fall into typological groups.

Two of the Museum’s gorgets, made for ‘Sawyer, King of Wickham-Hill’ (collection number 1985.0059.0387) and ‘John Neville, King of Mahaderree’ (collection number 1985.0059.0381), are identical in size and shape and the decoration is also very similar. They are likely to be by the same maker, while the inscriptions were added later by different hands.

The evidence suggests that the plates were mass-produced in a foundry and then purchased by engravers who provided a basic decoration leaving the centre blank for a suitable inscription. They seem to have been made much in the way trophies are produced.

The people who gave the gorgets to the Aboriginal people named may well have purchased the decorated blanks in anticipation of later use. The gorget made for Sawyer and that made for ‘Jemmy, King of Bolara Maneroo’ (collection number 1985.0059.0379) are also almost identical in shape but have different styles of engraving.

Four other gorgets in the Museum’s collection, made for ‘Jemmy, King of Big River’ (collection number 1985.0119.0001), ‘Mr Briney of Pialliway’ (collection number 1985.0059.0385) and ‘James Fearnought, King of Merigal’ (collection number 1985.0059.0382) also belong to this set.

Another two made for ‘Charley York, Chief of Bullangamang’ (collection number 1985.0059.0370) and ‘Timothy, Chief of Merricumbene’ (collection number 1985.0059.0378) also belong but have the distinction of having a coronet incorporated as part of the shape of the plate. The emu on the 20th century repair to Timothy’s gorget fits with the set described below as more modern although the kangaroo on the original portion is clearly of the 19th-century style.

The emu and kangaroo design was popular right up to the most recently produced gorgets. Four of the Museum’s most modern gorgets have the design. The style of decoration and the lettering on the inscriptions give them their more are modern date. The block lettering and bold heavily outlined designs contrast with the fussier, sketchier designs and roman or copperplate lettering of the early to late mid-19th century.

The shapes of the gorgets are also more rounded than the earlier plates. One gorget, made for ‘Bulgra, King of Arremutta’ (collection number A-ON 116) is dated 1920 which suggests that the modern gorgets were manufactured in the early 20th century.

Two of the four modern gorgets, made for ‘Albert, King of Georges River’ (collection number A-ON 119) and ‘Billy Kelly, King of Broadwater’ (collection number 1985.0059.0367), are very similar. They are almost identical in size and style of decoration. The kangaroos share the same scratching gesture and human-like eye and both creatures are very graphic and cartoon-like.

‘King Billy, King of the Barwon Blacks’ (collection number 1985.0059.0365) is similar to the last two but is a less professional, more naive design. Bulgra’s is the most modern-looking of all the gorgets and resembles advertising imagery of the 1920s. Both the emu and the kangaroo are very naive and cartoon-like with their human eyes and eyebrows. The snake design may have represented the ‘totem’ or ritual animal of King Bulgra.

Makers

Tracing the makers of the gorgets is difficult. Only two of the Museum’s gorgets have makers’ marks. The fine gorget made for Billy Hippie, described earlier, is marked ‘Twemlow, engraver, Sydney’. A copper gorget given to Peter, King of Tchanning, also noted above, has a stamped mark which reads ‘Hughes and Kimber, manufacturers, London’.

The off-centre, careless placement of the mark and the fact that it states ‘manufacturer’ rather than engraver or maker suggests it was a mass-produced blank gorget brought out to Australia for engraving. This gorget provides evidence that the gorgets became one of the commodities produced in England for the colonial Australian market.

Graham Walsh, in a note to the Museum of Victoria, observed that Lassetter and Co. of Sydney ‘semi mass-produced’ gorgets ‘with the king’s name and station being filled in as ordered’. [2] He noted that they repeatedly used ‘an identical style of engraving on their motifs’. Walsh’s remarks help confirm the observations given above made on the basis of the sample in the National Museum of Australia.

Emu and kangaroo designs

On 19 of the 33 gorgets in the National Museum of Australia’s collections are depicted an emu and a kangaroo acting as supporters to the central inscription. On one gorget, made for ‘Peter, King of Tchanning’ (collection number 1985.0059.0386) the kangaroo even has a joey peeping from its pouch. Many other gorgets also have the two creatures as supporters for their inscriptions.

With the waratah, these two creatures became the earliest icons or ‘symbols’ of Australia used by European colonists. The emu and kangaroo appeared as supporters on ‘the first flag designed and made in Australia ... flown at Richmond, New South Wales, early in 1806 ... known as the Bowman flag ... Inspired by news of Nelson’s victory of 21 October 1805 at Trafalgar, John Bowman designed and made the flag and flew it on his property, Archerfield’.

[3] The flag, now in the Mitchell Library, Sydney, was made to be a symbol of unity. On it was a composite of the English rose, Irish shamrock and Scottish thistle all on a Norman shield, icons for the heritage of the colonists. Australia itself was represented by the shield’s supporters, the emu to the right and the kangaroo to the left. It was ‘the first time, so far as is known, that these two supports, now so familiar on the Australian Arms, were ever used in this way’.

[4] The use of the emu and the kangaroo on Bowman’s flag indicates that at least by the turn of the 19th century they were recognised within the colony as the unofficial symbols of Australia. Therefore it is not surprising that King Bungaree’s gorget, the oldest known, had as its supporters the emu and kangaroo and many subsequent gorgets continued the tradition.

An anonymous writer eulogising Bungaree in 1859 claimed the emu and kangaroo as ‘the arms of the colony of New South Wales’.

[5] In fact, the emu and the kangaroo supported the unofficial Australian Coat of Arms and were included in the blazon of the official arms, granted in 1912 by King George V.

[6] The arms of New South Wales, granted in 1906 by King Edward VII, are supported by a lion and a kangaroo.

The armed forces did not acquire a distinctly Australian appearance until the late nineteenth century. The slouch hats and khaki uniforms which came to typify Australian soldiers were not adopted until the 1890s.

[7] Hat badges displayed Australian symbols such as the waratah for New South Wales, black swan for Western Australia and wattle for Queensland. However, it was the First Australian Horse which employed the emu and the kangaroo as the left and right supporters for its crest.

The Citizen Light Horse units were created privately and were usually ‘graziers, employers and professional men’.

[8] Mostly bushmen, they came from the same group of people who were presenting Aboriginal leaders with gorgets. Their use of the emu and the kangaroo on their own badges and on those they gave to Aboriginal people was no coincidence. The emu and kangaroo were icons of colonial Australian identity, allegorical symbols of the country.

Ogilvie and Gilmore, who made the gorget, discussed in an earlier section, for ‘Bobby, Chief of the Yulgilbar Tribe’, considered the emu and the kangaroo to be important symbols of Australian nationalism. Dame Mary Gilmore presented the gorget to the National Library of Australia in memory of her father, and reminisced about its manufacture. [9] The nationalism expressed in her sentiments and those she perceived in her father’s gesture are self-evident. Ogilvie and Gilmore used the presentation of a gorget to an Aboriginal man as an outlet for their National fervour.

It was thought out by my father and his kinsman, Mr Ogilvie, of Yugilbar [sic], about 1870 or 1871. ... My father first cut the form and size in cardboard, and I was present when the design and wording were discussed. Both men had a great belief in Australia and its future and said that, though then only a colony, it would one day be a continental nation and have its own coat-of-arms. What that coat-of-arms would be they could not guess, but they said its ‘supporters’ would be the kangaroo and the emu, these being Australian and belonging to no other country. ... The ‘supporters’ were drawn by Mr Ogilvie’s eldest son, then 14 years of age, and home from college.

The plate was made under my father’s direction. He also procured the wax and acid for the etching of the inscription, but who did the etching I do not remember. The breastplate was of burnished copper. ... Because both my father and Mr Ogilvie saw in the Yugilbar plate the forerunner of the Australian coat of arms, I decided that the commonwealth should have it. ... To-day the plate has lost its sheen, the makers and those for whom it was prepared are long gone, but the ‘supporters’ on it are, as expected, the ‘supporters’ of the coat-of-arms of Australia, and in this is the fulfilment of the dream my two dreamers dreamed. [10]

Footnotes

[1] CM Finney, To Sail Beyond the Sunset: Natural History in Australia 1699–1829, Rigby, Adelaide, 1984, pp 16–17.

[2] GL Walsh, letter from Mr GL Walsh to Mrs Christine Hogarth, Museum of Victoria, 21 June 1979. Quoted in part in Breastplates in the Museum of Victoria, manuscript, Museum of Victoria, Melbourne, 1979.

[3] F Cayley, Flag of Stars, Rigby, Adelaide, 1966, p. 57.

[4] Cayley 1966, pp 57–58.

[5] Anon, ‘Memoir of Bungaree in the Australian Home Companion (1859)’ in Chapman Ingleton, G (ed.), True Patriots All, or News from early Australia – as Told in a Collection of Broadsides, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1952, p. 268.

[6] FG Phillips, ‘Coats of arms’ in The Australian Encyclopaedia, vol. 2, Grolier Society of Australia, Sydney, pp 434–36, 1963, p. 435.

[7] Australian War Memorial, Colonial Military Gallery: Soldiers of the Queen, texts accompanying ongoing exhibition, 1988.

[8] I Jones, The Australian Light Horse, Time-Life Books and John Ferguson, Sydney, 1987, p. 20.

[9] WF Whyte, ‘Supporters of 'Australian' Coat of Arms’, cutting from unnamed newspaper in National Museum of Australia, EO Milne Collection, file no 85/310, folio 83, 1949.

[10] Gilmore in Whyte, 1949.