Keeping our land strong

Norman Bell, Gunditjmara, 2014:

We are doing the stuff that we were doing hundreds and thousands of years ago. Keeping our land strong.

Gunditjmara and Kirrae Whurrong peoples of south-west Victoria keep connections to their countries alive.

Significant places such as the Framlingham Forest and the 6800-year-old network of eel channels will be there for the future because Gunditjmara and Kirrae Whurrong peoples have fought for them.

Old objects, like those in museum collections, are also valued for the history they hold.

Thomas Day, Gunditjmara and Yorta Yorta, 2014:

When I see these old artefacts ... I get a glimpse of something – of the past.

Augustus Strong, who took up land at St Marys, collected these hunting and ceremonial objects, such as the feather skirt below, in the early 1840s. He left no records of his relationship with the local Aboriginal people.

People today link these objects to the conflict with colonists west of St Marys, known as the Eumarella War.

Geoffrey ‘Possum’ Clark-Ugle, Peek Whurrong/Kirrae Whurrong/Thap Whurrong, 2014:

These artefacts show it was hard in invasion times for [the British] to come here without our people putting up a fight ... That fight still continues ... for that recognition of who we are and where we come from.

Old objects

Augustus Strong gave 14 Aboriginal objects from Victoria, including this feather skirt, to the British Museum in 1847, when he returned to England to train for the priesthood. He probably collected them between 1842 and 1844, while he was based at the ‘St Marys’ cattle station on the Hopkins River, near Warrnambool.

These mementos of his time as a settler in the region are among the earliest Aboriginal material from Victoria acquired by the British Museum. After three years back in England, Strong returned to Australia and worked for many years as a cleric in Melbourne.

New objects

Ben Church, Gunditjmara, 2014:

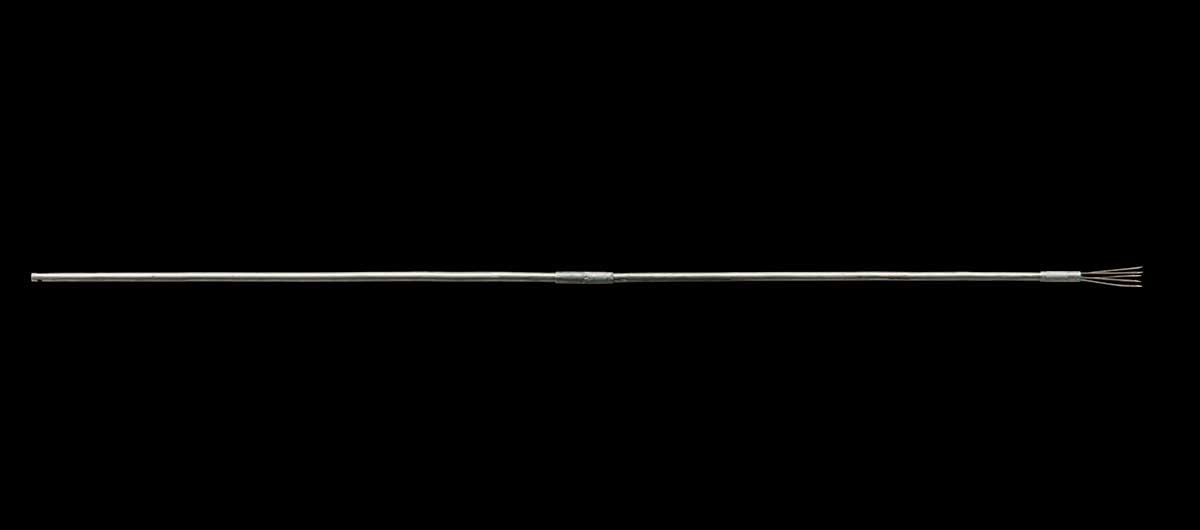

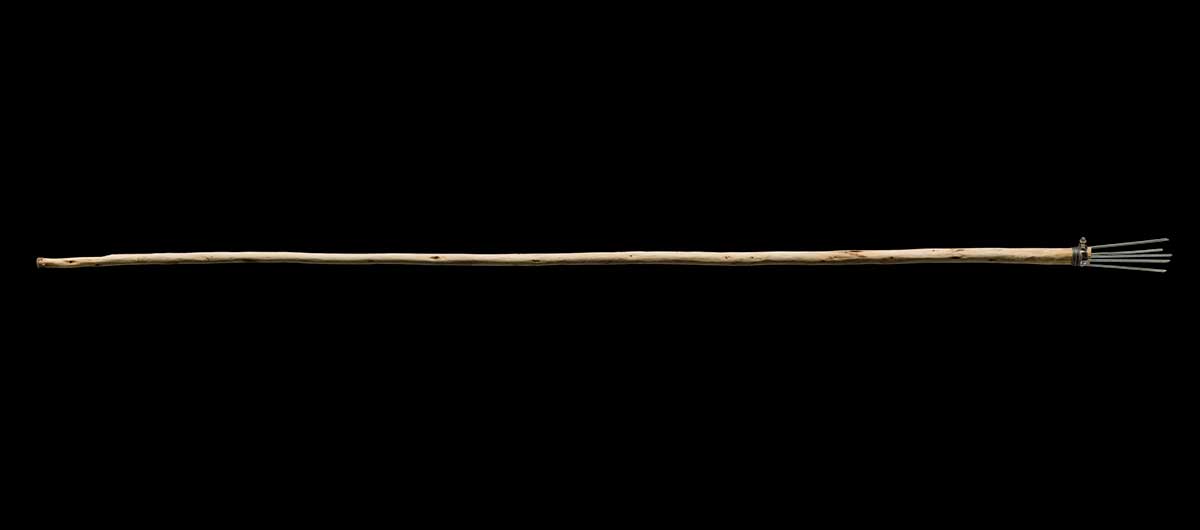

We’re making the [eel] spears, maybe not in the exact same way as they were traditionally, but we’re doing it – trial and error, you know. We’re tapping into our traditional knowledge.

Gunditjmara are working today to restore some of the landscape engineered by their ancestors for the management and harvesting of kooyang (eels). This trap has been used in recent times for catching eels. You can see the areas where the trap has been repaired after being damaged during use.

Thomas Day, Gunditjmara and Yorta Yorta, 2013:

When I go on country I’m looking for a small window in time, to let us look into the past, to see what it may have looked like once. That makes me happy. When I see these old artefacts I feel the same. I get a glimpse of something. Of the past.