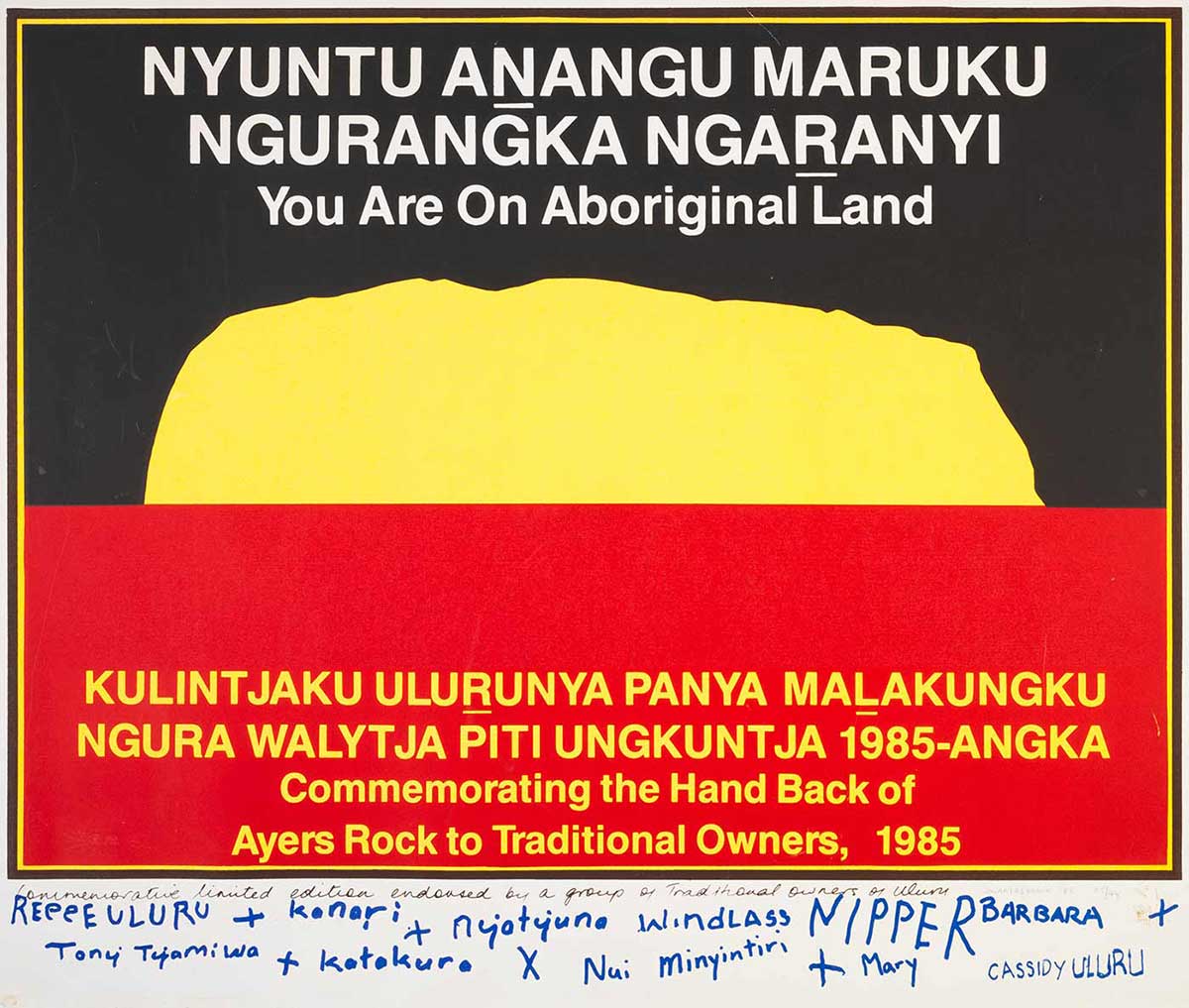

When the Hawke government handed back the title deeds for the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park to the Anangu in October 1985, it ended decades of determined lobbying by the traditional owners to have their rights recognised.

Traditional owner Barbara Tjikatu, 2015:

My family were here for Handback. They really felt strongly about not leaving their country. It’s grandfather’s and the ancestors’ land.

An ancient and continuous history

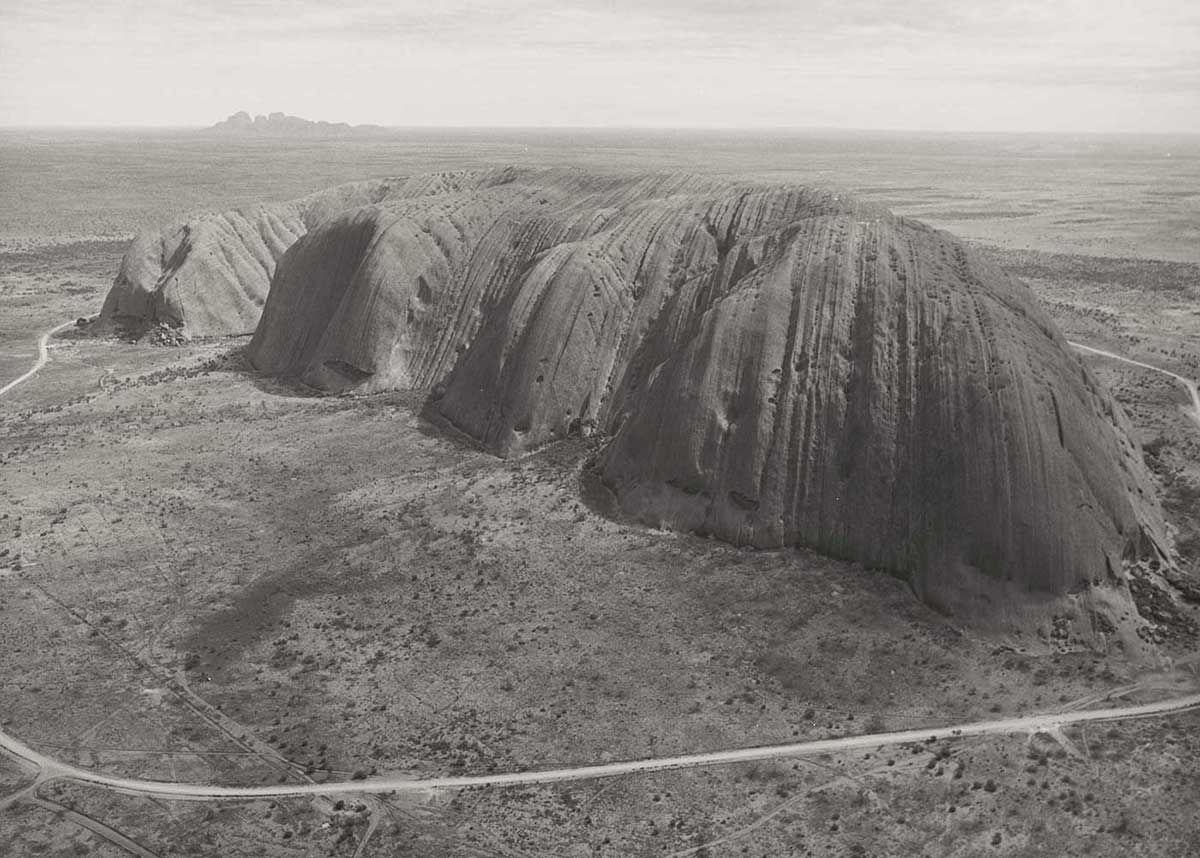

Located in the heart of the nation, Uluru is one of Australia’s most recognisable landmarks. It is a red sandstone monolith that rises 348 metres above ground.

For the local Anangu, Uluru has been there forever and is a deeply sacred place. Both Uluru and the nearby rock feature of Kata Tjuta show physical evidence of feats performed during the creation period that are told in the Tjukurpa stories.

Tjukurpa is the belief system that guides every aspect of the lives of the Anangu. The Anangu believe the landscape was created by ancient beings, and that they are direct descendants of those beings.

The protection and management of the lands around Uluru and Kata Tjuta are considered to be intrinsic Anangu responsibilities.

European contact

The first recorded European to visit and climb Uluru was explorer William Gosse. In 1873 he named it Ayers Rock after Sir Henry Ayers, Chief Secretary of South Australia.

In the 1890s a scientific team researched the geology, mineral resources, flora, fauna and First Nations culture of the area and confirmed its unsuitability for farming.

From 1920 Uluru and Kata Tjuta were included in the South West Reserve, part of a series of areas set aside for First Nations people.

Few non-Indigenous people visited the area until the 1940s. The first road to Uluru was not built until 1948. It brought miners and tourists, and the Ayers Rock National Park was declared in 1950. Tourism gradually grew, and a new airstrip was built to allow visitors to fly in.

Kata Tjuta was added to the park to create the Ayers Rock–Mount Olga National Park in 1958, managed by the Northern Territory Reserves Board. The Anangu people were discouraged from visiting the park, although many continued to travel across their homelands to hunt, gather food, visit relatives and participate in ceremonies.

First Nations activism

Although some Anangu left the area, the Wave Hill Walk-Off by Gurindji stockmen in 1966 inspired many Anangu to return to their country. They lobbied the Northern Territory Government for the rights to their lands, and expressed concern about the effects of mining, pastoralism and tourism, and about the desecration of sacred sites.

However, the area was excluded from the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 when it was declared the Uluru–Kata Tjuta (Ayers Rock–Mount Olga) National Park in 1977.

Despite continual lobbying by the Pitjantjatjara Council and the Central Land Council, the Northern Territory Government resisted efforts to recognise the traditional owners’ rights. It wanted title transferred from the Commonwealth to the territory, with a reduced title for the Anangu and no control in park management.

The stalemate lasted until the Hawke government was elected in 1983. In November that year it was announced that the Aboriginal Land Rights Act would be amended and the title for the Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park transferred to the Anangu.

Handing back Uluru

The ceremony to hand back the title took place at the base of Uluru on 26 October 1985. More than 2,000 Indigenous and non-Indigenous people looked on as Governor-General Sir Ninian Stephen presented the title deeds to Uluru–Kata Tjuta.

The traditional owners then signed an agreement to lease the park back to the Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service for 99 years.

A board of management was established with a majority of Anangu members. The park continues to be jointly managed.

Traditional owner Reggie Uluru, 2015:

The land was being returned to its original owners, so we were happy. Long ago Anangu were afraid because they were pushed out of their lands. And because of that Anangu left. But now a lot of people want to come back. That’s good. It’s our place, our land.

Further developments at Uluru

In 1987 the natural values of the Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park were recognised when it was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List.

In 1994 the park was also added to the list for its extraordinary value as a living cultural landscape.

A cultural centre was opened in 1995. And in 2000 the Sydney Olympics torch began its journey on Australian soil with a circuit around the base of Uluru.

Climbing Uluru

The Anangu have always believed that climbing Uluru is a violation of Tjukurpa. The tourist trail up Uluru followed the line of the traditional trail taken by ancestral Mala men upon their arrival at Uluru.

Although William Gosse was probably the first European to climb Uluru, the first recorded climb was in 1936. The number of people climbing the rock rose slowly, with a growing number of fatalities resulting in the installation of a chain on a portion of the climb in 1966.

There was no consultation with traditional owners as further changes were made, such as extending the chain in 1976. The climb was marketed heavily and attracted more and more tourists. Sometimes people were prevented from climbing because of poor weather conditions (heat, rain, wind) or for cultural reasons.

Over the years, 37 people lost their lives climbing Uluru, and many more have needed rescuing. The Anangu feel deeply responsible for visitors’ injuries and deaths.

There were many problems associated with climbing Uluru. The climb itself was difficult. The presence of thousands of visitors caused erosion, and human waste and rubbish left on the top of Uluru washed down into waterways below. The shield or tadpole shrimp that lives on the rock has been driven to near-extinction through being trampled by walkers.

Most importantly, Uluru is a sacred site for the Anangu.

Closing the climb

In 2010 the Uluru–Kata Tjuta Plan of Management confirmed that the board would look at closing the climb permanently when certain conditions were met. For example, when less than 20 per cent of visitors made the climb.

By 2015 the number of people climbing fell to 16.5 per cent. In November 2017 the board voted unanimously to ban the climb from October 2019.

The Uluru climb was permanently closed after a ceremony at Uluru on 26 October 2019, exactly 34 years after the government officially returned the lands to the Anangu.

In our collection

You may also like

References

History of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park

‘Traditional owners given title to Uluru’, The Canberra Times, 27 October 1985.

Ayers Rock Resort, ‘Closing the Uluru climb’, 13 April 2018.

Julian Swallow, ‘On this day: Aboriginal Australians get Uluru back’, Australian Geographic, 7 November 2013.