On 28 April 1996, 35 people were killed and many more injured in a mass shooting at the historic Port Arthur tourist precinct in south-east Tasmania.

Armed with three high-powered firearms, the perpetrator murdered the owners of a nearby guesthouse before driving to Port Arthur where he shot multiple visitors and staff in and around the site. The young Hobart man later murdered a hostage at the guesthouse, before he was captured by police as he fled the building.

The massacre provoked national debate about private ownership of guns, especially automatic weapons.

Within weeks of the tragedy, Australian Prime Minister John Howard implemented critical changes to gun safety legislation with bipartisan state, territory and Commonwealth support. The endorsement offered by Coalition partner and Nationals leader Tim Fischer, and Labor’s Kim Beazley, leader of the Opposition, was crucial to achieving the reforms.

In November 1996 the perpetrator was sentenced to imprisonment with no eligibility for parole on 73 charges, including 35 life sentences for murder.

Australian firearms laws

Before 1996, Australia’s states and territories had differing laws relating to gun ownership.

Colonial gun laws were inherited from British common law, with very few changes made to develop local licensing provisions. During the earliest phases of colonialisation, access to guns was limited to settlers, police and military personnel overseeing convicts.

When firearms became more commonly used – for hunting, protection and keeping pests away from crops and livestock – instances of criminal misuse increased, for example by bushrangers and among some violent mining communities.

Many thousands of people from First Nations communities were killed by armed colonists in frontier conflicts.

Government control over the purchase and use of weapons increased during the early decades of the 20th century, in response to outbreaks of criminal activity in larger cities. By the mid-20th century, gun regulation across the country was powerfully influenced by growing groups of recreational shooters and wildlife preservationists.

Although the Commonwealth government had banned the import of military-style, rapid-firing weapons in 1991, many remained in circulation, unregistered or unsafely stored. Some state politicians advanced aspects of gun safety but they were often defeated by powerful pro-gun lobby groups.

In some parts of early 1990s Australia, any person with a regular shooters licence could legally hold any number of rapid-fire weapons and ammunition. Tasmania had the weakest guns laws in the country.

A nation divided over gun safety

Many Australians across the media, politics and community vehemently disagreed over gun safety during the aftermath of the massacre.

Those in favour of gun safety advocated for tighter and uniform legislation across the country.

Anonymous, ‘35 reasons why our leaders must act’, Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 2 May 1996:

In Tasmania, 35 people are dead because a killer was able to arm himself with a semi-automatic rifle. Your responsibility is to make it illegal to own these guns, illegal to be in possession of them, illegal to obtain the bullets they fire. All this is within your power and the public demands nothing less.

Pro-gun groups protested against limiting rights for responsible owners who used firearms for pest-control, hunting or sports.

Ted Drane, Sporting Shooters' Association of Australia (SSAA), 7.30 Report, ABC TV, 9 May 1996:

You’re dealing with private property. In my case it’s a firearm that is considered being banned – it’s a .22 rim-fire, self-loader. I’ve had it for 36 years. And you tell me today that it’s a danger to public safety and that if I keep it, I’ll go to jail. That’s pretty hard for people to comprehend, as why they can have something for so long and all of a sudden it’s illegal, it’s a danger to public safety.

Road to changing gun laws

During the early months of his term as prime minister, John Howard moved to enact uniform national legislation banning pump-action, automatic and semiautomatic firearms. The National Firearms Agreement limited the sale or supply of weapons, set out minimum licensing, registration and safe storage requirements.

Applications for licences were subject to background checks and a mandatory ‘cooling-off’ period. Compulsory safety training was introduced and applicants were required to supply a ‘genuine reason’ for owning a firearm. Self-defence was not an acceptable reason.

These measures were largely unpopular with conservative state governments. They were opposed by pro-gun groups, who had often voted for the Coalition government due to its previous support of the gun lobby.

John Howard was challenged at pro-gun rallies across the country and was perceived to be bullying state governments into changing their laws. Others in the community, especially gun safety groups, were supportive of Howard’s decisive approach and his refusal to back down on the issue.

Gun buyback scheme

The National Firearms Agreement included a ‘buyback’ scheme to remove privately owned weapons from circulation, funded by an increase to taxes. An amnesty provision allowed gun-owners to surrender newly banned weapons without legal consequences. Some received financial compensation.

During the buyback, more than 650,000 firearms – both banned and legal – were surrendered to the police or destroyed.

Impact of tighter gun laws in Australia

John Howard’s stance on gun law reforms remains one of the most celebrated aspects of his term as prime minister and is a watershed in Australian history.

John Howard, House of Representatives, Australian Parliament House, 6 May 1996:

I have some understanding of the depth of community feeling on this issue and a desire, as I find it amongst my fellow Australians, to grab this very tragic moment to bring about a profound cultural shift in the attitude of this community towards the possession and the use of destructive weapons.

In the wake of the tragedy at Port Arthur, gun safety became an issue of national concern and one that was less easily appropriated by politicians of varying perspectives.

Adherence to National Firearms Agreement regulations differ across states and territories, where community attitudes vary on aspects including issuing licences to supervised children, waiving the cooling-off period and the continuing use of high-powered weapons by shooting club members.

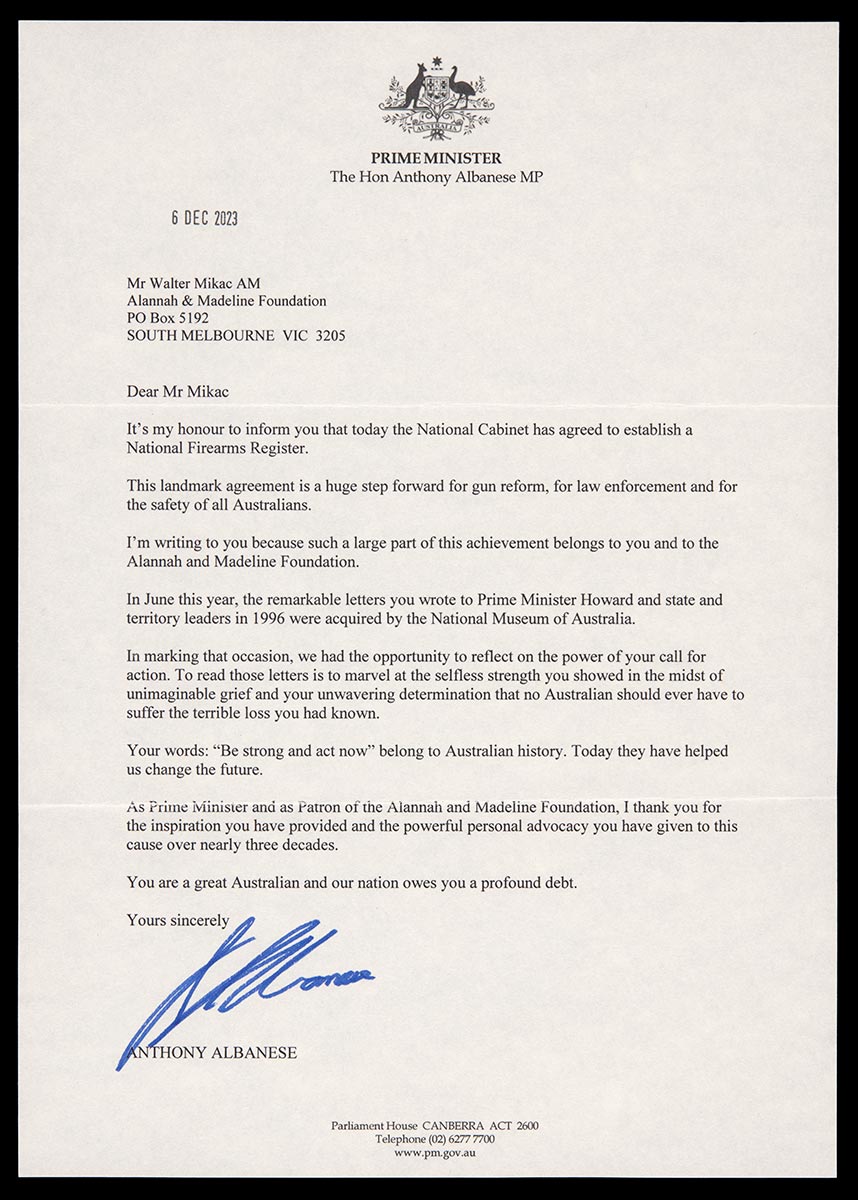

Although the National Firearms Agreement recommended the establishment of a nationwide register of firearms across jurisdictions, it was not until December 2023 that Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s National Cabinet agreed to establish a National Firearms Register.

Explore Defining Moments

References

John Howard on guns, politics and power, 2016, ABC

A brief outline of events on 28 April 1996, Port Arthur Historic Sites

1996 National Firearms Agreement, Attorney-General’s Department (PDF 225kb) on Trove

Philip Alpers, ‘The big melt: How one democracy changed after scrapping a third of its firearms’, in Reducing Gun Violence in America: Informing Policy with Evidence and Analysis, Daniel Webster and Jon Vernick (eds), The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2013.

Simon Chapman, Over Our Dead Bodies: Port Arthur and Australia's Fight for Gun Control, Sydney University Press, 2013.

Andrew Leigh and Christine Neill, ‘Do gun buybacks save lives? Evidence from panel data’, in American Law and Economics Review, vol. 12, no. 2, pp 509–557, 2010.

Rebecca Peters, ‘Rational firearm regulation: Evidence-based gun laws in Australia’, in Reducing Gun Violence in America: Informing Policy with Evidence and Analysis, Daniel Webster and Jon Vernick (eds), The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2013.