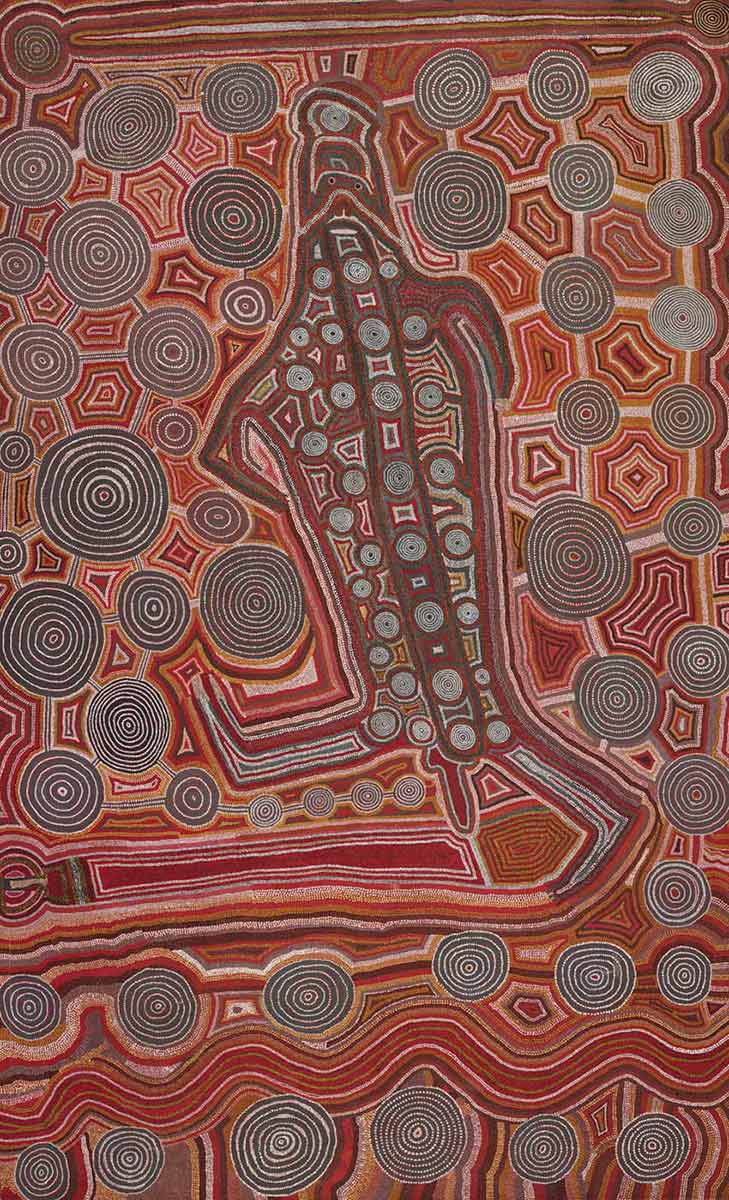

In 1971 a group of Aboriginal artists from the government settlement at Papunya began painting traditional designs using acrylic paints and small boards.

This was the beginning of the Western Desert art movement that has become one of Australia’s most recognisable art forms and which led to the formation of the first Aboriginal arts business, Papunya Tula Artists cooperative, in 1972.

Hetti Perkins and Hannah Fink:

It was here [at Papunya] that one of the most significant art movements in Australian history emerged – its genesis made all the more remarkable by its humble origins.

Papunya movement background

Aboriginal rock painting and carving in Australia is a tradition stretching back at least 40,000 years. The artwork was a reflection of Aboriginal understandings of their world but this system of beliefs was challenged by the arrival of white settlers in 1788.

By the mid-1800s, through violence, disease and dispossession, the Indigenous population had dramatically decreased. From the early 1900s the federal government introduced a policy of assimilation intended to ensure Australia had a uniform white-dominated culture.

One aspect of this assimilationist policy was the start, in the 1930s, of the Hermannsburg School art movement at Hermannsburg Mission in the Northern Territory. The Western Arrente artists’ work was some of the first by Aboriginal people to interpret their country through western-style art – typically landscape watercolour painting.

Papunya

In Central Australia the federal government built assimilationist settlements where Aboriginal people, having been forcibly removed from their homelands, especially those from remote areas, could be gathered and provided services that would promote their integration into white society.

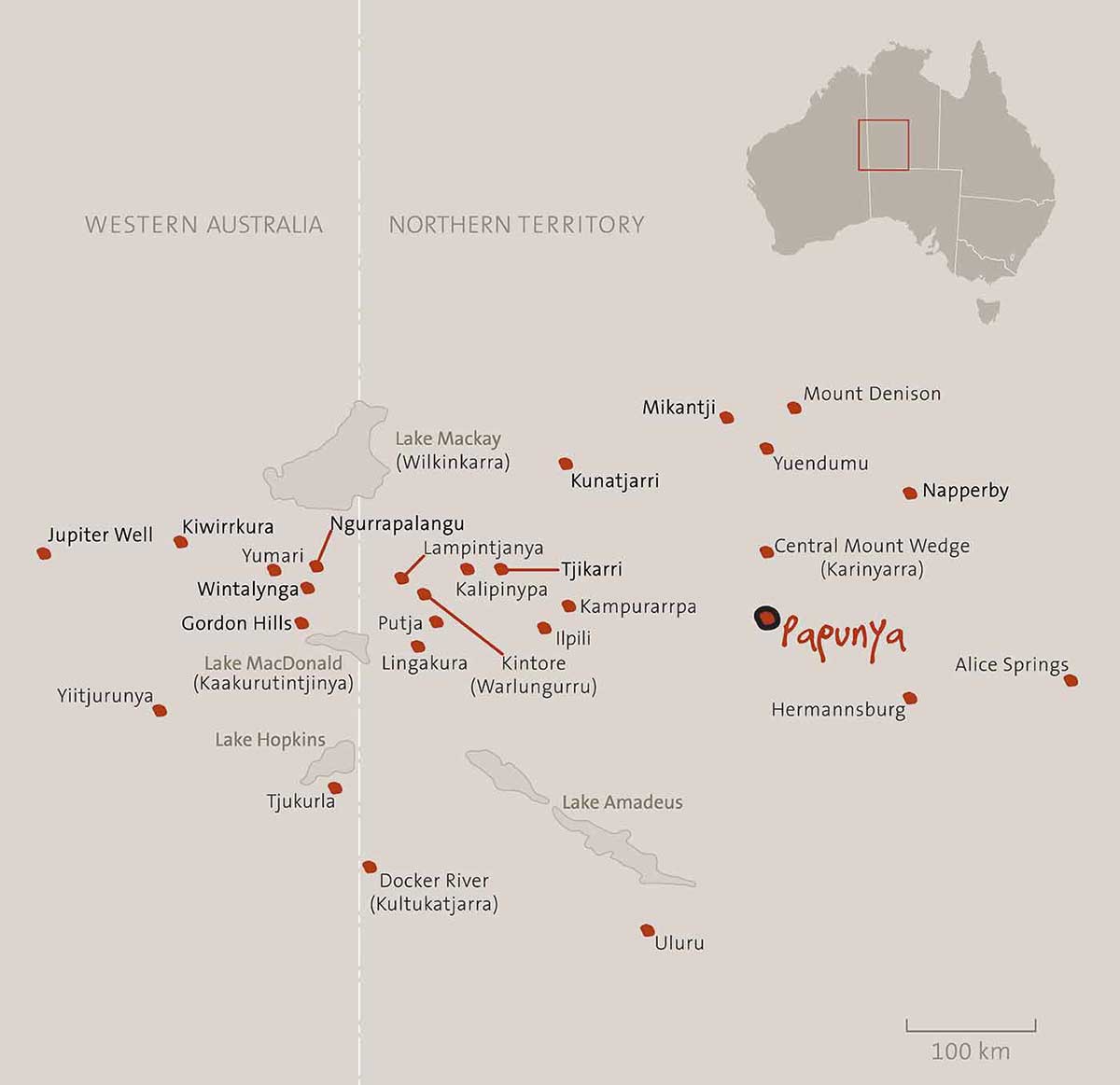

Papunya, 240 kilometres west of Alice Springs, was one such community, founded in 1959. By 1970 there were 1400 mainly Pintupi and Luritja people, but also Warlpiri, Kakatja and Anmatyerr groups, living at Papunya. This was twice the population the settlement had been designed to accommodate.

The early years of Papunya were extremely difficult as families that had been relocated from their traditional lands were ravaged by disease. During 1963 and 1964 close to half the people in the settlement died.

Desert art movement

The men involved in the mural painting were inspired by what they had done and began gathering in small groups away from the women and children to paint their stories.

Initially there was no thought that this was a commercial undertaking but in August 1971, Kaapa Tjampitjinpa’s painting, Men’s Ceremony for the Kangaroo, Gulgardi jointly won the Caltex Golden Jubilee Art Award alongside a European-style painting.

For the first time, Aboriginal art was viewed in the same context as white art and was judged to be of comparable quality. It made Kaapa the first Aboriginal Australian to win a contemporary art award.

Soon after, a young school teacher Geoffrey Bardon took a selection of paintings to Alice Springs and raised $1300 for the artists. It was a sensation throughout the community; the artists were making money painting from their own designs, not western interpretations. Over the next six months, more than 600 paintings were sold.

Not everyone in the community was pleased with the exposure of intimate Aboriginal knowledge to the outside world and there was opposition to aspects of the early paintings. Over time, the artists changed their styles to hide any secret or sacred knowledge incorporated into the designs.

Art in Papunya

In the late 1960s some men in Papunya began creating artwork in the Hermannsburg style. In 1971 Bardon arrived in the town.

He became interested in the sinuous patterns his students would draw in the playground sand and realised they had deep societal meaning. He proposed creating a public mural for the local school using these images.

The children were reluctant to participate, but eventually a group of elders met Bardon and presented him with a design, based on the honey ant dreaming, that they approved for the project.

Over a period of weeks in September a rotating group of Aboriginal men including Old Bert Tjakamarra, Bill Stockman Tjalpatjarri, Long Jack Phillipus Tjakamarra, Old Mick Tjakamarra and Kaapa Tjampitjinpa painted the mural.

Papunya Tula Artists cooperative

The movement grew as more men became interested in painting and in October 1971 they formed the Papunya Artists cooperative within the Papunya School. The white administration of the community was opposed to the cooperative because it was an entirely Aboriginal-run organisation and therefore existed in opposition to the assimilationist policy.

The name Papunya Tula was born at a gathering of painters at Charley Creek near Alice Springs in June 1972. Bardon asked the men ‘What do you want to call the company?’. The Pintupi man Charlie Tarawa (Tjaruru) immediately said, ‘Papunya Tula’, which is the name of a hill outside the town that means ‘a meeting place for all brothers and cousins’.

As Bardon said:

… that morning Papunya Tula became a living idea, and everyone was happy.

The Papunya Tula Artists cooperative was Australia’s first Aboriginal arts company and foreshadowed the federal government shifting its Indigenous policies from assimilation to self-determination.

Papunya goes international

There were trying times in the first years of the Papunya Tula company. Bardon was forced to leave due to sickness he believed was brought about by stress arising from his dealings with Papunya’s white administrators.

For a while, the painters had difficulty accessing materials and markets, but a series of motivated arts administrators assisted the group throughout the 1970s while the artists created newer and more individual styles.

By the 1980s the group had secured national exposure through state gallery exhibitions and then, in the latter part of the decade, international recognition with exhibitions in New York, London, Auckland, Paris and Venice.

Papunya Tula became a bridge between Aboriginal and white culture and in the process evolved as one of Australia’s most recognisable art forms.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

Geoffrey Bardon, Papunya Tula: Art of the Western Desert, McPhee Gribble, Ringwood, Victoria, 1991.

Geoffrey Bardon and James Bardon, Papunya: A Place Made After the Story, The Miegunyah Press, Carlton, Vic. 2004.

Hetti Perkins and Hannah Fink, Papunya Tula: Genesis and Genius, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2002.