In 1848 the New South Wales Government set up a Native Police force, consisting of Aboriginal troopers under European officers. They operated mainly in what is now southern Queensland, quelling Aboriginal resistance to European settlement.

NSW Governor Sir Charles FitzRoy to Earl Grey, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, 12 August 1848:

I have reason to believe that the establishment of this force will not only have the effect of checking the collisions between the white Inhabitants and the Aborigines … but I am also sanguine in the hope that it may prove one of the most efficient means of attempting to introduce more civilized habits among the native tribes.

Policing the settlement

Once the Blue Mountains were crossed in 1813, European settlement in Australia spread rapidly outwards.

For some years the authorities tried to place limits on the area to be settled, but this proved fruitless. The lure of good grazing land beyond the formal boundaries was too much.

Squatters took their flocks to whatever ‘vacant’ land they could find, and explorers surveyed areas further and further afield.

The land was not vacant, of course. European settlement steadily encroached on Aboriginal land, and conflict between the two groups escalated.

Aboriginal people killed animals and sometimes settlers. For their part, the Europeans ruthlessly suppressed Aboriginal opposition. Official policy was to achieve harmony between the two groups, and to protect both from each other’s violence. But beyond the reach of colonial authorities the only law was often that of revenge and reprisal.

Early attempts to police the borderlands

By the late 1830s the colonial authorities gave up the attempt to limit settlement. Instead they tried to regulate the expansion. The so-called ‘Squatting Act’ of 1836 (amended in 1839) set up a Border Police Force, to be funded by the squatters themselves.

This was unpopular, and the Border Police were not very effective. They were drawn largely from military convicts, and settlers accused them of being drunken and disorderly.

The biggest problem was that they were spread very thin, and did not have the manpower to protect either settlers or Aboriginal people. By this time the settled areas extended as far as the Darling Downs.

In the 1830s and 1840s there were various attempts to employ Aboriginal men. Some were attached to both the Border Police and the older Mounted Police, who patrolled the areas of formal settlement, to help track offenders. There were also several attempts to set up a Native Police Force, drawing on precedents elsewhere in the British empire.

Increasing conflict

In the 1840s settlement expanded rapidly in what is now Queensland (then still part of New South Wales – Queensland became a separate colony in 1859). This settlement brought new levels of conflict with Aboriginal people. For a while those carting goods up the Great Dividing Range west of Moreton Bay needed military escorts.

While there were cases of outright violence against settlers, Aboriginal groups generally adopted tactics of raiding and pilfering. One settler claimed to have lost seven tonnes of sweet potatoes. Others reported dozens of cattle speared – often just the tongues and some of the fat were taken.

Settlers retaliated by shooting or poisoning Aboriginal people, who took their revenge by killing settlers.

The settlers were at a loss how to deal with opponents from a completely different culture. The government wanted to protect both groups from the cycle of resistance and reprisal.

The solution, it seemed, was to recruit a body of Aboriginal police, who would better understand and be able to deal with Aboriginal opposition. The proposed Native Police Force would remain under European command.

Plans for the Native Police

To avoid conflict of interest within tribal groups, Aboriginal people from other groups far afield would be employed. This idea was not universally applauded.

In Moreton Bay, police magistrate Captain John Wickham commented that hostility between Aboriginal groups might actually make the Native Police excessively harsh in their dealings with the local inhabitants.

Nevertheless, the governor of New South Wales, the moderate and conciliatory Sir Charles FitzRoy, felt that a Native Police Force might bring calm to the northern districts, and at the same time be a way of integrating Aboriginal people into colonial society.

On 15 June 1848 the NSW Legislative Council passed an Act detailing the following year’s budget for the colony. The final item provided for up to £1,000 ‘to defray the expense of a small corps of Native Police to be employed beyond the Settled Districts in the Sydney District’.

The reference to the Sydney district was probably to distinguish this force from an earlier Native Police Force at Port Phillip (Melbourne). The new force would operate largely, though not entirely, well north of Sydney.

Operations of the Native Police

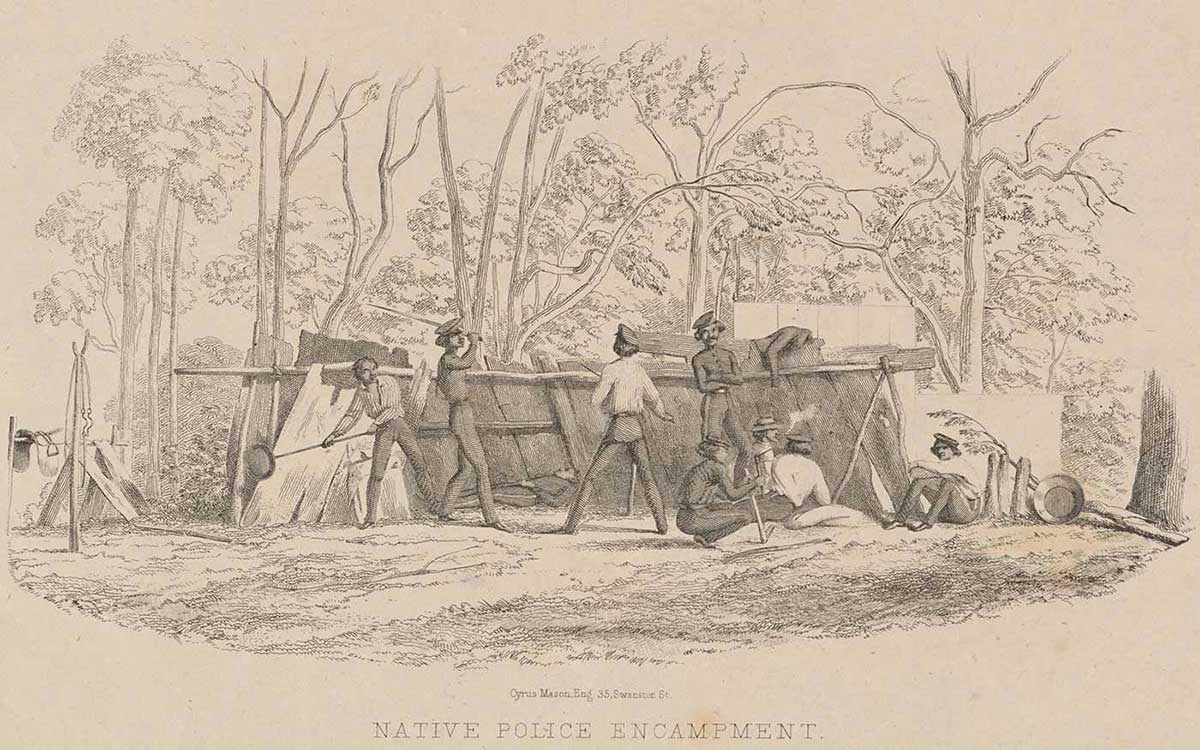

In August 1848, 28-year-old Frederick Walker was appointed to command the Native Police. Walker had only arrived in Australia four years earlier, but he had friends in high places. He had some knowledge of Aboriginal languages and was thought to understand Aboriginal culture.

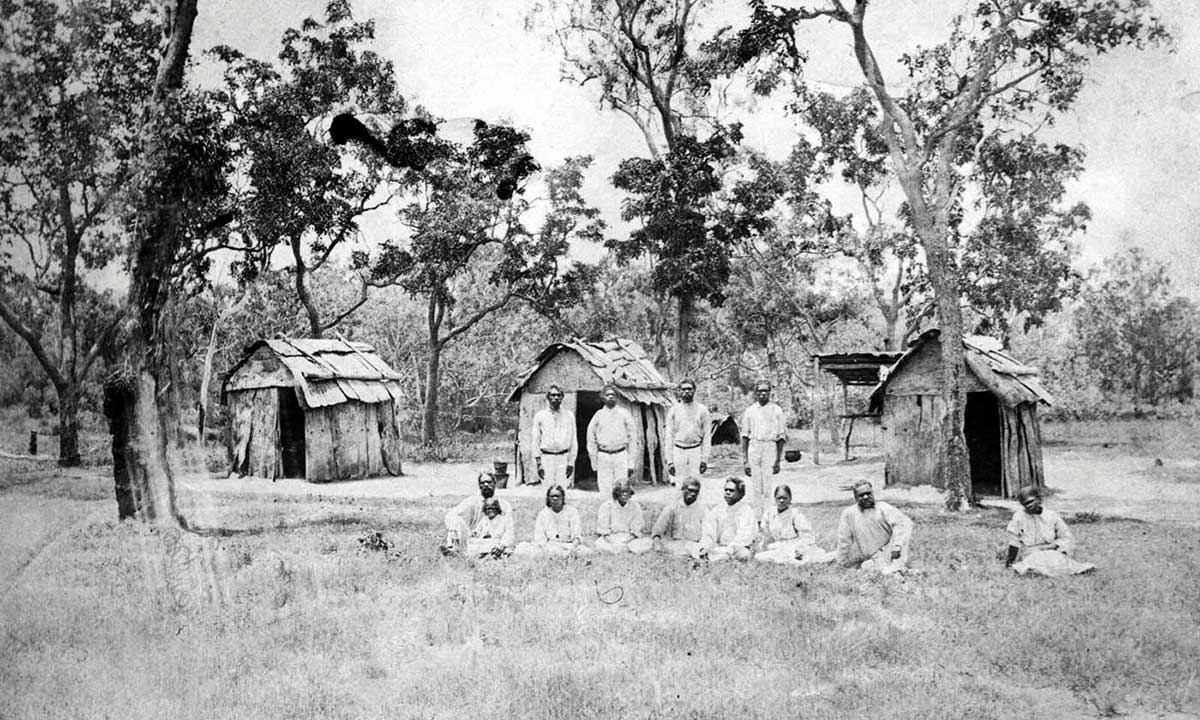

Before his appointment Walker had been Clerk of Petty Sessions in Wagga Wagga. He recruited his initial 14 troopers from four different Aboriginal groups in the Murrumbidgee, Murray and Edwards rivers areas of southern New South Wales.

Despite the fact that his men spoke four different languages, he trained them into a cohesive group. By May 1849 they were in Queensland.

Walker and his men immediately launched punitive ambushes and actions against marauding Aboriginal groups. With their superior arms, and their willingness to pursue their opponents into broken country, which had seemed too dangerous to the settlers, Walker and his men met with immediate success.

The force steadily grew, but its methods remained extremely violent – at times amounting to attempted annihilation of Aboriginal groups. A government inquiry was launched in 1854, and Walker was eventually dismissed. The Native Police continued as a body, in one form or another, until the 1960s.

In our collection

Explore defining moments

References

‘Australian native police’ (accessed 5 February 2020)

H Burke et al, ‘The Queensland Native Police and strategies of recruitment on the Queensland frontier, 1849–1901’, Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 42, no. 3, 2018, pp. 297–313.

Leslie Edward Skinner, Police of the Pastoral Frontier: Native Police, 1849–59, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Qld, 1975.