Wanyubi Marika, 2005:

I can feel the spirit of the old people coming through these bark paintings, the stories coming through the travels of the Djang'kawu from Burralku to Yalangbara.

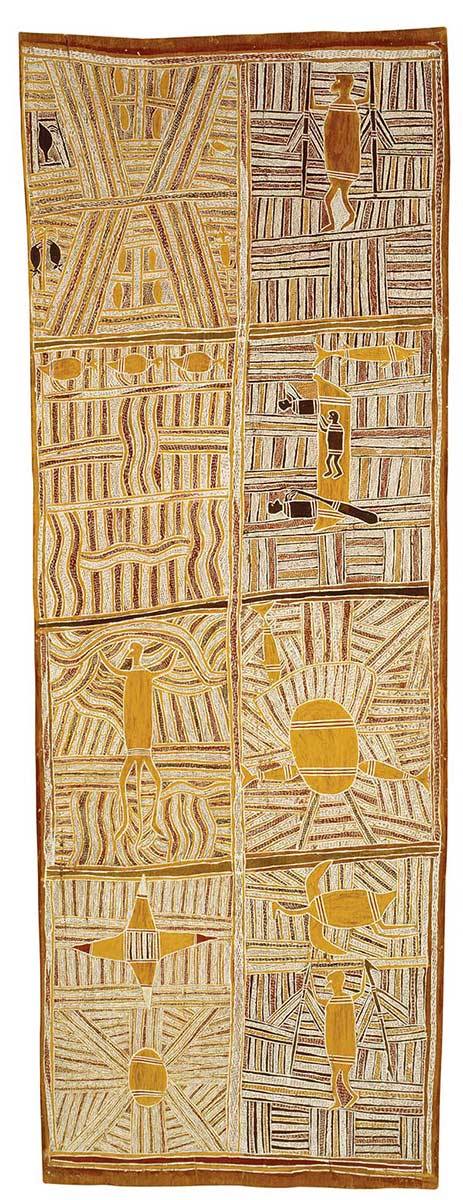

The Yalangbara paintings, prints and sculptures belong to one of the great bodies of Australian art devoted to a particular place. These images with their interplay between the figurative and the abstract, are concrete manifestations of the ancestral past and provide us with an enticing glimpse into the Yolngu universe.

Along with songs, dances, ceremonial objects and other aspects of ceremonial law, these images are part of the madayin, the Rirratjingu sacred inheritance and property originally gifted by the Djang'kawu.

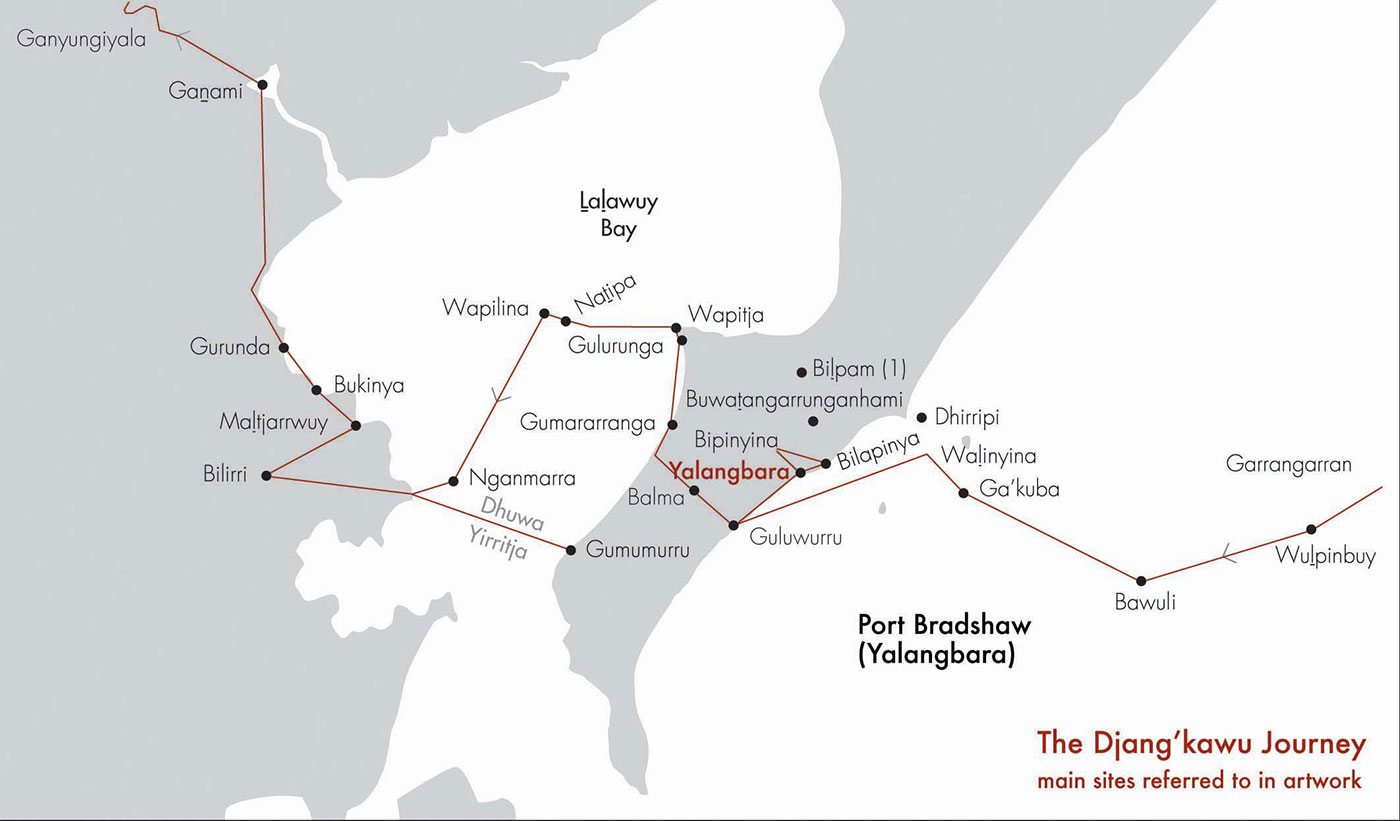

On one level the paintings are like maps tracing the Djang'kawu journey (goyurr) at the 50 or so named sites across Yalangbara. Some of these works may refer to one place while the more comprehensive narratives can encompass highlights of the entire journey across the Port Bradshaw area.

These themes are illustrated in the exhibition works that include some of the earliest barks from the 1930s, the rare crayon drawings commissioned by Professor Ronald Berndt in 1947, large barks from the Art Gallery of New South Wales collected in 1959, through to the contemporary prints, barks and sculptures made by both established and emerging Rirratjingu artists.

While the art here illustrates episodes of the Djang'kawu story across Yalangbara, it also contains other symbolic meanings.

Political meanings

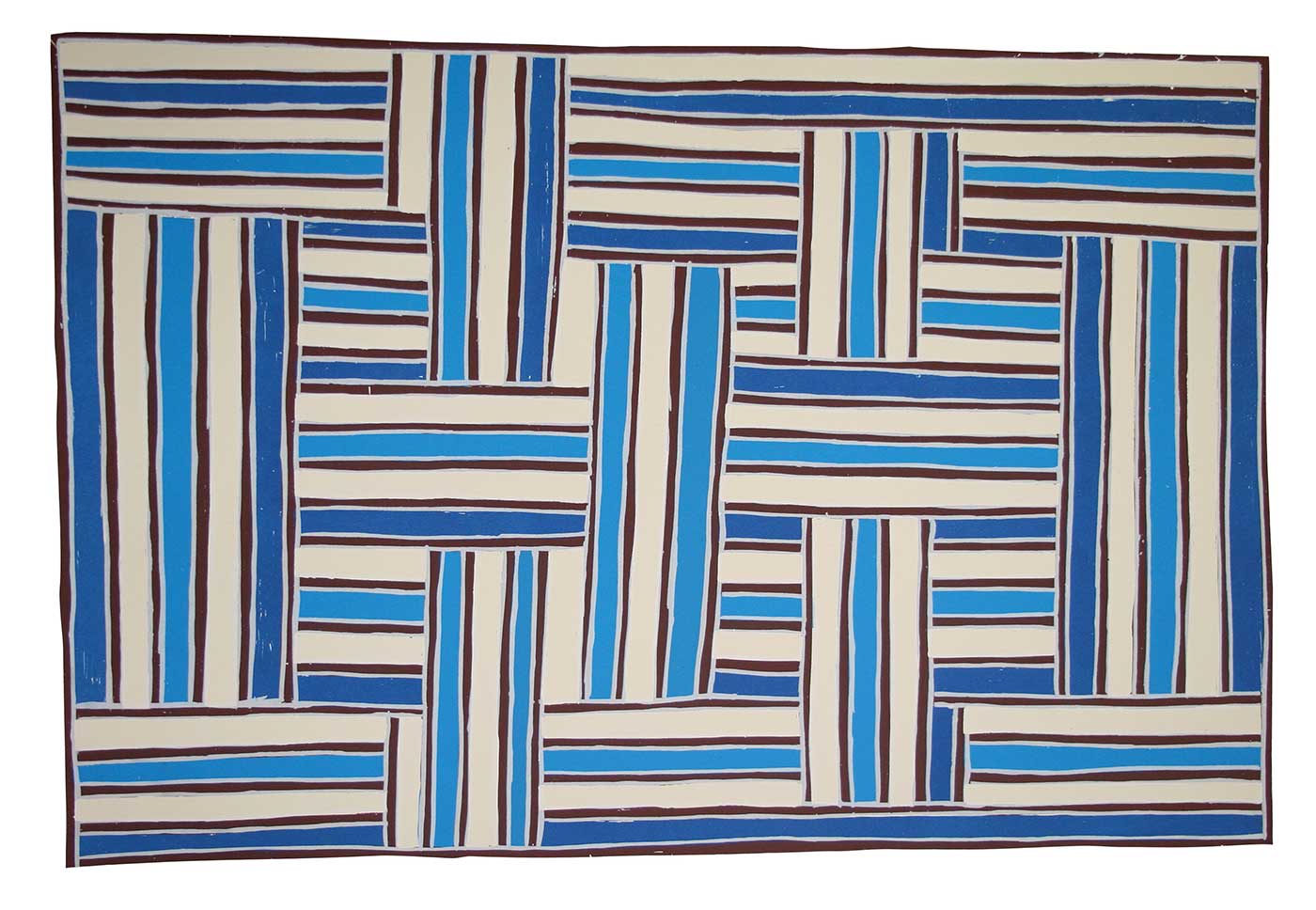

Yolngu art is in fact unique in the way it simultaneously expresses people's social identities, their ancestral law and ownership of land. The most important images are the clan designs (miny'tji) that were traditionally painted onto people's bodies and objects during ritual. Each clan has its own distinctive set of geometric clan patterns, such as the linear designs of the Rirratjingu.

The Yolngu art expert Howard Morphy notes that ancestors like the Djang'kawu have a core set of designs, and each set is divided between the clans whose countries they created. So while each Dhuwa clan has its own distinctive designs there are also similarities with the other clans' patterns to indicate their common ancestral legacy.

The designs therefore mark the ancestors' journey, and establish the relationship between people and the land. This is why miny'tji are regarded as deeds to country and appear in important political documents like the famous Yirrkala bark petition.

The Rirratjingu assert their ownership of the entire Yalangbara area through their art. There are also two branches of the Marika family that claim different sides of the peninsula: the eastern or Yalangbara side and the western Gulururnga side, and this is reflected in the differentiation between in their clan patterns.

Dhuwarrwarr's son Jimmy Barrmula Yunupingu, explains:

There are differences in the designs for the two sides. If I draw four lines [in the clan design] they can recognise that it's Yalangbara. If I draw three lines that's Gulurunga. That's the difference. Because they are each separate. Yalangbara area is [comprised of] Gulururnga side on the west side and Yalangbara on the east side.

Painting and aesthetics

Apart from their social and political meanings, Morphy reveals that the designs also have a definable aesthetic.

The crosshatched patterns of the miny'tji create an optical shimmering effect called bir'yun. It's this brightness that endows a painting with its ancestral power because it's seen as emanating from the wangarr themselves.

This quality is present in the Rirratjingu patterns that symbolise the sunlight gleaming on the hot white dunes at Yalangbara, or the emanating light of the rising or setting sun.

The gleaming rainbow lorikeet feathers used in Rirratjingu and other Dhuwa ceremonial decorations is also part of this aesthetic.

These feathered ceremonial items were among the cherished possessions the Djang'kawu brought to Yalangbara.

You may also like