The Not Just Ned exhibition developed by the National Museum of Australia features objects which help to tell a story of Irish settlement in Australia.

To the Irish, Australia offered regular work, good food and, above all, opportunity. Historians argue over how quickly the Irish were able to rise through the different social and economic levels of colonial society. In Australia they could own land and the Irish settled across the colony. Some helped to open up and develop remote pastoral and mining regions.

Featured here are the stories of writer Mary Durack and her pioneering family, pastoralist Samuel Pratt Winter, explorer Robert O’Hara Burke, rebel turned politician Charles Gavan Duffy, the Sisters of St John of God, settler brothers John and Robert William von Stieglitz, colonial governor the Earl of Belmore and anthropologist Daisy Bates.

Agriculture and pastoralism

Kings in Grass Castles

Kings in Grass Castles (1959) and Sons in the Saddle (1983) were the books in which Mary Durack captured the saga of pastoral Australia.

The Duracks and their relatives from the Tully, Costello and Kilfoyle families, were mostly poor Irish immigrants who arrived in the late 1840s and early 1850s.

Their drive, initiative and family cohesiveness took them from small settlements around Goulburn to the Kimberleys in the far north-west of the continent, where they founded a pastoral empire.

The most prominent Duracks were Patrick (‘Patsy’), who came to Australia in 1853, and his son, Michael Patrick or ‘MP’. Patsy made a fortune and lost it in the Great Depression of the 1890s.

MP, born in Australia, went into partnership with two Irishmen, Francis Connor and Dennis Doherty, and until his retirement in 1950, managed the vast Connor, Doherty and Durack properties that stretched across the Western Australian and Northern Territory borders in the Kimberley.

Horses, cattle, river crossings, long stock drives, endless night camps under the stars and many wearisome hours in the saddle — this was the life of those Irish pastoral settlers and their European and Aboriginal drovers.

Patsy Durack died in 1898, still mourning the death of his wife, Mary. At the end, he called out for her and his Aboriginal employee and friend, Pumpkin: ‘Tell Pumpkin to fetch up the horses, Mary. I am ready now.'

Crate full of air

In his poem ‘Bogland’, Seamus Heaney paints a picture of a noble but extinct creature:

They’ve taken the skeleton

Of the Great Irish Elk

Out of the peat, set it up,

An astounding crate full of air

Irish settler Samuel Pratt Winter brought the enormous antlers of one of these extinct animals from Ireland back to his homestead, Murndal, in the Western District of Victoria. More than 1.6 metres wide, they still delight and surprise visitors.

Megaloceros giganteus was the largest deer ever known. Often known as the Irish elk, its range actually extended from Ireland to central Russia. The antlers would have reminded Pratt Winter of the great bogland spaces of the ‘old country’, where such remains were being found in the 19th century.

In the new world of Australia, Pratt Winter surrounded himself with visible echoes of the old world of Ireland and Europe. Well educated, this avid amateur collector was always looking for things to adorn his Australian domain. Still flourishing at Murndal is a great oak, sprung from an acorn of a tree listed in the ‘Domesday Book’, the famous survey of England begun by William the Conqueror in 1085.

Pratt Winter also sent home to his sister, Arabella, seeds from an old cypress tree in Rome that had been planted by Michelangelo. He hoped this would allow him to establish at Murndal ‘a grove in honour of a most extraordinary genius, architect, poet and sculptor’.

By the early 1860s Pratt Winter had made a considerable success of his property at Murndal, raising fine wool for export and sheep and cattle for meat. Pratt Winter’s distinctive ‘SPW’ mark became a familiar sight for wool buyers.

Exploration and rural settlement

Tried in the desert

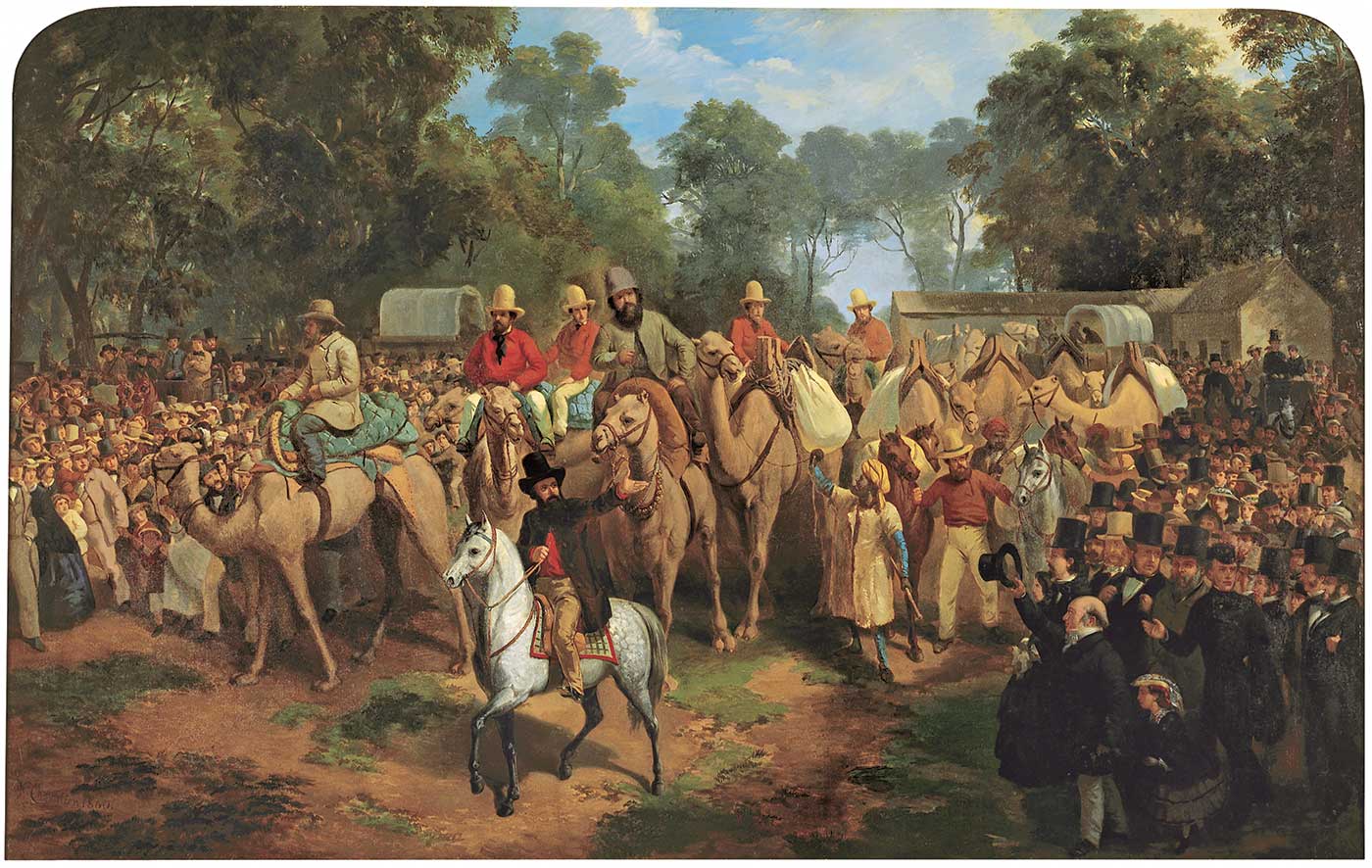

On 20 August 1860 there was a carnival atmosphere at Royal Park, Melbourne. A crowd, estimated at between 10,000 and 15,000, had come to watch the men of the Victorian Exploring Expedition — with their piles of equipment, wagons, camels and horses — make their departure.

Their aim was to be the first European explorers to cross the Australian continent from south to north. There was much confusion as the expedition got underway: a camel bolted; a horse, frightened by the camels, threw its rider, breaking her leg; and artists and photographers jostled to record the historic scene.

One of the artists making sketches for a bigger canvas was Swiss-born Nicholas Chevalier. In his Memorandum of the Start of the Exploring Expedition, Chevalier places the Irish leader of the expedition, Robert O’Hara Burke, centre-stage. He is perched on his horse in a heroic pose at the head of the column and waving goodbye to another Irishman, Mayor Richard Eades of Melbourne.

Burke, and his eventual co-leader, Englishman William John Wills, made a very different re-entry into Melbourne, in their coffins, on 28 December 1861. Both had crossed the continent, but they died at Cooper’s Creek in South Australia on their epic return trek. As historian Manning Clark wrote, ‘The English and the Irish had been tried in the desert and found wanting.'

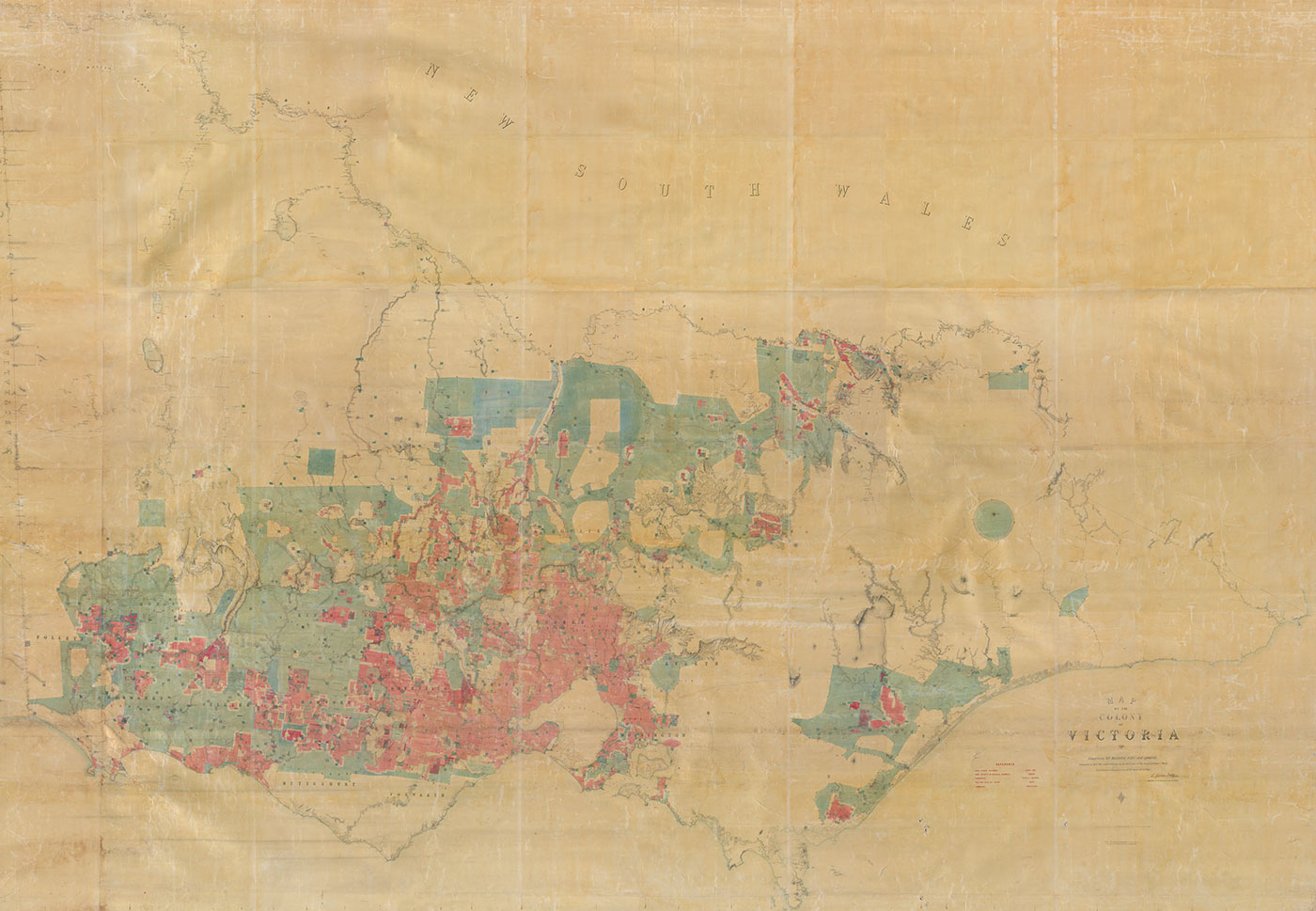

Duffy’s big map

Charles Gavan Duffy, a follower of the ‘Young Ireland’ nationalist party in the 1840s, was arrested in 1848 and tried five times, unsuccessfully, for high treason. Ireland was then in the grip of the Great Famine, and Duffy felt that one practical solution to the problems besetting the country would be to make it possible for poor tenant farmers to buy and own their land.

Nothing came of his efforts in that direction, however, and in 1855, despairing of the British parliament’s ability to improve conditions in Ireland, he settled in Melbourne.

In 1856 Duffy was elected to Victoria’s first Legislative Assembly. During the second half of the 1850s, the easily won alluvial gold, which had attracted thousands of immigrants, began to run out, and a major issue of the day was what to do with this restless surplus population.

In Victoria, as in Ireland, Duffy supported the idea of giving access to land to those with little capital. Farming would provide a ‘healthy and pleasant pursuit’ for ex-diggers who might otherwise become ‘discontented and dangerous to public safety’. And for his Irish countrymen, who had been driven from the land in Ireland, Duffy saw the prospect of a ‘more prosperous home on the genial soil of Victoria’.

Duffy’s ‘Land Act’ (Victorian Lands Act 1862) attempted to cater for this land hunger. In his Guide to the Land Law of Victoria, Duffy referred to a ‘large map’, hanging in Melbourne’s Parliament House, which showed the distribution of land ownership in Victoria.

Apart from areas unsuitable for agriculture, official surveyors identified 4 million hectares where men who had been labourers in England, or tenant farmers in Scotland or Ireland, could become owners of the soil. Intending settlers could ‘select’ blocks of up to 260 hectares for a small initial sum, with the rest to be paid as rent over a number of years.

The Act failed because the great pastoralists or squatters, especially in the Western Districts, were able to evade its provisions and acquire the land for even larger sheep and cattle runs.

Tropical habit

On 6 June 1907 an amazing sight was to be seen at Beagle Bay, Dampier Peninsula, Western Australia. Wading ashore, through water over a metre deep, were six Irish nuns, Sisters of St John of God, in black habits. In wet clothes and bare feet they walked 11 kilometres to their new home, the Pallottine Fathers’ mission station.

The sisters were part of a party of nine led by Mother Antonio O’Brien. Seven came from the order’s mother house in County Wexford, Ireland, and two from Perth.

In their early years at Beagle Bay, and later in Broome, the St John of God sisters wore their characteristic long black habits. When Irishman Father John Creagh arrived in 1916, he was horrified at their living conditions. Among other improvements, Creagh ordered white bales of cotton from Perth, and the sisters gradually adopted lighter, white habits more suitable for work in the tropics.

The sisters today are working actively for reconciliation, having acknowledged that in the past they were one of those agents of change that had a destructive effect on the culture and society of Indigenous Australians in the north-west.

Many of that Stolen Generation of children, educated by the nuns and boarded in their institutions, have spoken favourably of the Irish sisters, recalling how they genuinely seemed to care about them.

Not long before she died in 2007, after 67 years at Beagle Bay, Sister Bernadette O’Connor was asked whether she wanted to go home to Ireland. ‘Why should I want to do that?’ she replied. ‘You are my people.’

Contact

Wathaurong weapons

It is widely acknowledged that the development of European Australia since 1788 has occurred on land taken from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Irish settlers profited as much from these acts of dispossession as any other group.

The earliest major European settlement around Melbourne, or what was then the Port Phillip district, began in the mid-1830s. Prominent among some of the early settlers who came to Port Phillip from Tasmania (Van Diemen’s Land) around this time were two young Irishmen, John and Robert William von Stieglitz.

They took up sheep runs near Geelong and at Ballan, 80 kilometres west of Melbourne. Robert’s attitude towards those who had occupied the land before the settlers set up their runs was typical of the times: ‘The general rule is, if the people cultivate or grass the land they have a claim on it, but these creatures did neither.' It was the perfect settler excuse for the expropriation of land, by force if necessary.

Unsurprisingly, the von Stieglitz brothers soon came into violent conflict with the local people. Robert, in particular, tells of going out to hunt Aboriginal people who had attacked and killed settlers. When they returned to Ireland in the 1850s, the brothers took home a remarkable collection of weapons picked up after one such expedition.

Among the earliest Aboriginal material collected in the Port Phillip district, these artefacts are a reminder of the reality of frontier conflict in early Victoria.

Cities

The Australia House

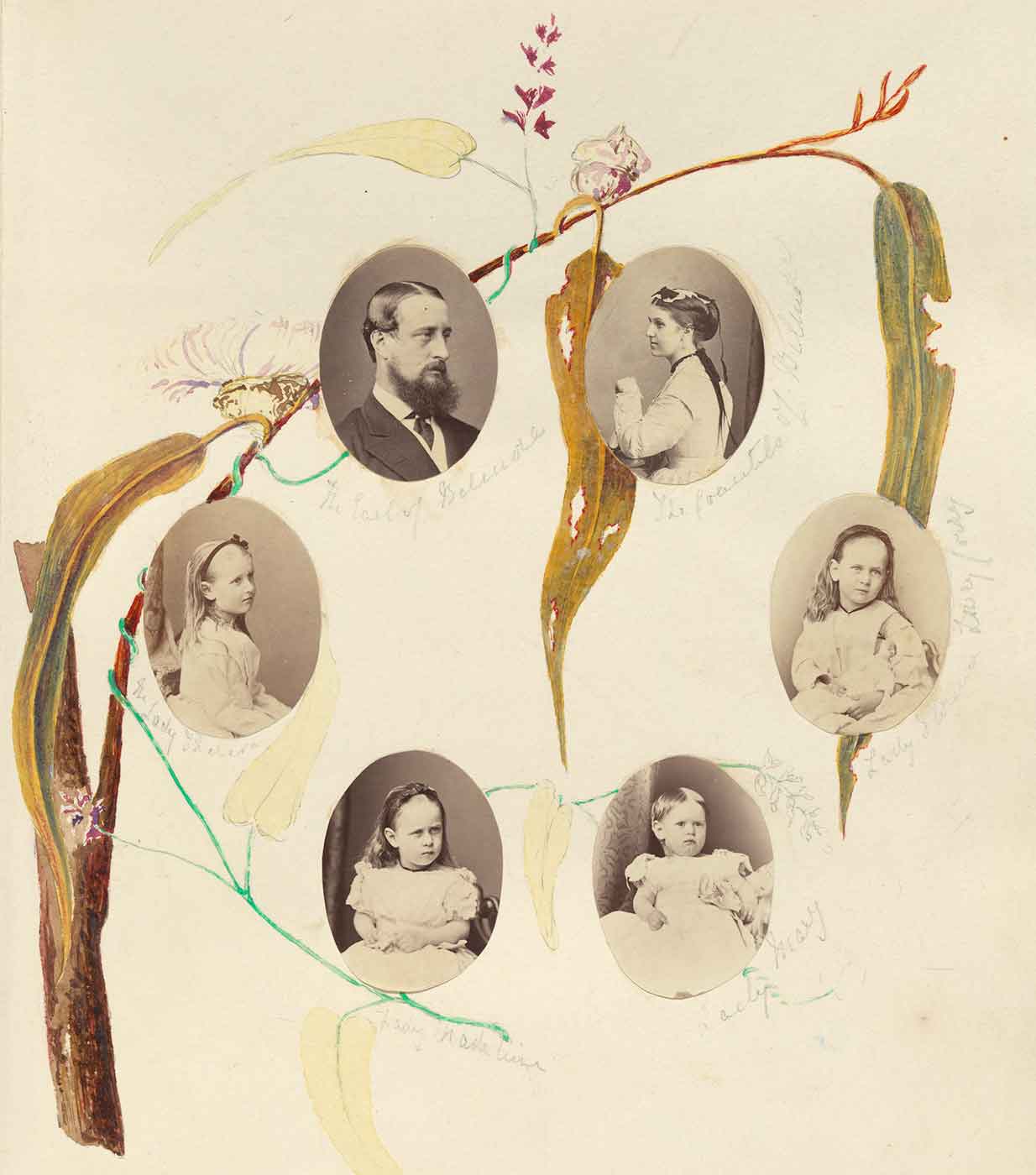

In 1868 the fourth one of Ireland’s leading peers of the realm, accompanied by his wife, Honoria, landed in Sydney to take up his post as the new governor of New South Wales. The couple were given a hearty welcome and quickly whisked off to Government House, where they spent the rest of the day at a formal reception, shaking hands with the colony’s rich and influential citizens.

Few probably paid much attention to one brief sentence in the lengthy report of the governor’s arrival issued the next day: ‘The four children of the Earl and Countess of Belmore were brought on shore at a subsequent hour of the day.'

For the next four years, Government House was also a family home to the four young Belmore girls: Therese, Florence, Madeleine and Mary. Lady Belmore’s delicate condition, and the summer heat, led the family to a country retreat, Throsby Park in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales. It was here that the couple’s first son was stillborn.

Another son, Armar, was born in Government House in May 1870. His wife’s poor health, however, caused Lord Belmore to ask for an early recall to Britain, and the family left Sydney in 1872.

The people of the city thought highly enough of their governor and his wife to present the children with a doll’s house on their departure. Known to the family ever after as the ‘Australia House’, it may have reminded them, in the cold northern winter, of the sunlight and warmth of New South Wales.

The fourth Earl of Belmore needed a well-paid job. The expenses of his Irish estate and a growing family led him to accept the post of governor of New South Wales in 1867. He arrived in Sydney in 1868 with his wife and four young daughters.

Apart from his considerable administrative abilities, and his skill at managing the colony’s unruly politicians, Belmore was appreciated for his extensive travels to meet the people. Everywhere he encouraged local agricultural and railway development, describing himself as a ‘practical man of business’.

In all, he made 16 trips around the colony by rail, steamer, buggy and on horseback, before the family returned to Britain in 1872.

Contact

Daisy Bates

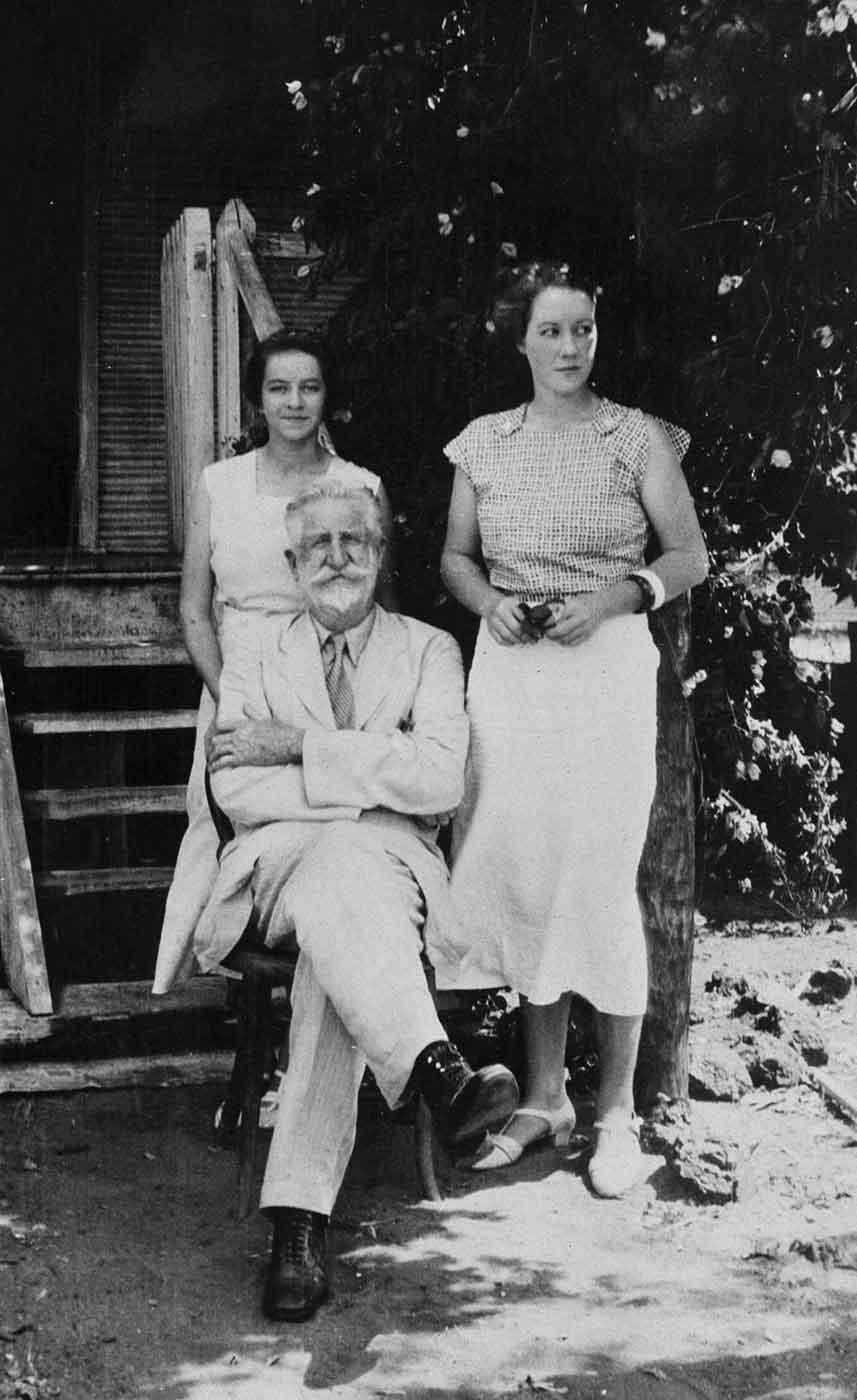

Daisy O’Dwyer, a young Catholic domestic servant from County Tipperary, arrived in Townsville, Queensland in 1884. She died in Adelaide in 1951, by then better known as Daisy Bates, famous in the English-speaking world through her widely read writings about Indigenous Australians.

Bates held views and attitudes now seen as unacceptable. In her book, The Passing of the Aborigines, published in 1938, she made false claims about the widespread existence of Aboriginal cannibalism. People of part-Aboriginal descent she dismissed as worthless, often in extreme language. But Bates did record an immense amount of Aboriginal culture, and these records are now invaluable.

Despite living in a tent in the desert, Bates always maintained a formal appearance. As a royalist, deeply committed to the British Empire, she hosted a number of royal visitors to the Nullarbor, in whose honour she organised Aboriginal performances and demonstrations.

In 1934, the year of the Duke of Gloucester’s visit, Buckingham Palace made her a Companion of the British Empire (CBE).