The Not Just Ned exhibition developed by the National Museum of Australia features objects which help to tell a story of the contribution of Irish immigrants to Australia through culture and sport. It also explores people’s reconnections with Ireland.

The old prejudice against the Irish has all but gone. In its place is an acceptance of the central role of the Irish in Australian history since 1788. Today ‘Irishness’ is seen as contributing to a sense of fun, humour and enjoyment that lightens the burdens of life.

Stories featured here include those of boxer Les Darcy, footballers Jim Stynes and Tadhg Kennelly, champion horse trainer Dermot Weld, centenarian nun Sr Brenda Browne, Rose of Tralee winner Kathryn Feeney, broadcaster Claire Dunne and leading Indigenous artist and businessman John Moriarty.

The craic

John Wayland, Irish piper

John Shaw Wayland died, forgotten, at Nazareth House Nursing Home, Geraldton, Western Australia in May 1954. But once he had been the toast of the town.

During the First World War, he would play his pipes as he escorted local recruits for the Australian Imperial Force to the station. The townspeople gave him a little medal for that.

Wayland was born in Ireland in 1868, the year the last convict ship, carrying Irish Fenian rebels, went from Britain to Western Australia.

By the late 1890s Wayland was one of Ireland’s best-known traditional pipers, playing the Irish, or uillean, pipes, and a founder of the Cork Pipers Club.

In 1912 he came to Perth, bringing with him a set of rare uillean pipes. For many years his playing was a feature of events such as St Patrick’s Day, first in Perth and later in Geraldton, where he settled.

On Anzac Day 1938 Geraldton residents were moved when they heard Wayland play the old lament, ‘The Flowers of the Forest’. Perhaps he had seen again some of those young faces of men he had accompanied to the station but who never returned home.

A place to pray

In the Catholic church a monstrance is a most religious and highly significant vessel. This modest monstrance was used in the 1920s and 1930s in O’Shea’s Railway Hotel in Katherine in the Northern Territory.

Once a month the Catholic priest from Darwin would travel down to Katherine to say mass in the O’Shea’s hotel, where the monstrance was placed on the bar, which served as an altar.

Tim O’Shea came to Australia in 1900 and acquired mining and bush skills in northern Queensland. In 1907 he returned to Ireland to marry Catherine O’Keeffe.

The couple later settled in the Northern Territory where O’Shea worked as a prospector, blacksmith and, finally, owner of pubs including the one at Katherine and Tattersall’s Hotel at Borroloola.

As good Catholics, the O’Sheas had mass said in their hotel by visiting priests, and their simple family monstrance is a relic of those days, still treasured by their descendants.

Irish in sport

In loving memory

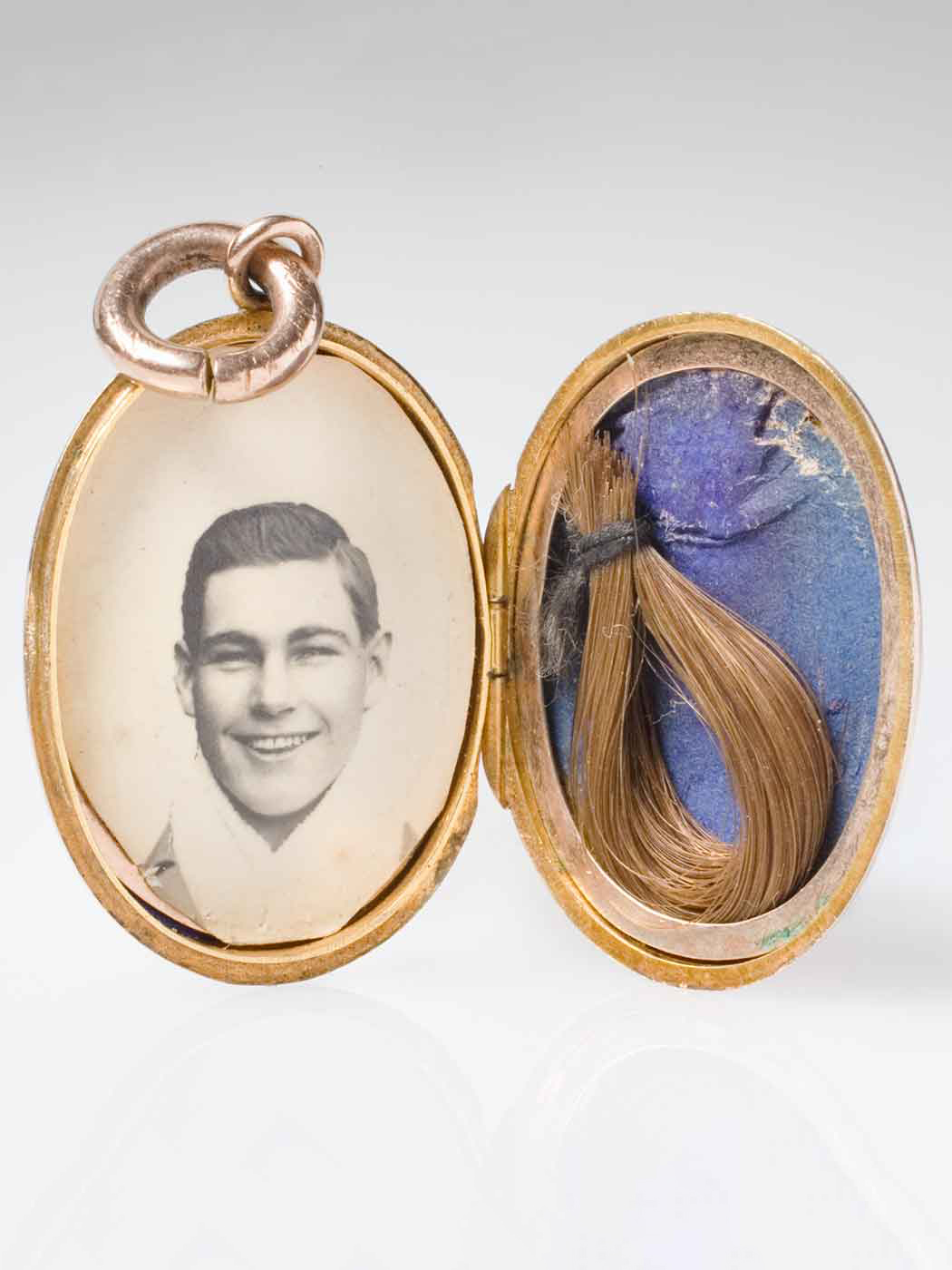

On 24 May 1917 in a room in a hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, Australian boxing champion, Les Darcy, aged 21, died from pneumonia contracted after a bout of septicaemia.

At Darcy’s bedside that day was his sweetheart, Winnie O’Sullivan, who cut off a small piece of Darcy’s hair that she kept, along with her favourite photo of him, in a small golden locket. When O’Sullivan died in 1974, the locket was discovered among her possessions. Her family had been unaware of its existence.

It later came to light that O’Sullivan’s brother, Maurice, a great mate of Les Darcy, carried the locket at the end of his watch chain for many years. He would show it to anyone who asked.

Of Irish Catholic descent, and a faithful Catholic himself, Les Darcy rose to boxing fame in the early years of the First World War. This success allowed him to build a house for his mother and to assist his poor family.

In the heated atmosphere of Australia’s conscription debates in 1916, Darcy slipped secretly away to America where he intended to make enough money from his boxing career to ensure his parents could live comfortably, and then to enlist for war service.

Many in Australia, some in high places, accused him of cowardice, and in America he was unable to obtain fights that paid him well. When Darcy’s body was returned to Australia he was given a hero’s funeral and buried under a Celtic cross.

He was adopted by the Catholic community who saw him as unjustly persecuted, as he had only wished to help his family, and then do his duty for his country.

The ‘Irish experiment’

The Australian Football League’s so-called ‘Irish experiment’ began in 1982, when the Melbourne Football Club’s legendary coach, Ron Barassi, travelled to Ireland to watch some Gaelic football. Barassi believed that the two games had many similarities, and that the Irish game could offer a source of untapped talent for the league.

One Irishman attracted to Australia by Barassi was Jim Stynes. And an exceptional recruit he proved to be. In 1991 Stynes became the league’s first and only overseas player to be awarded the prestigious Brownlow Medal for the season’s ‘fairest and best’. Stynes became an official ‘legend’ of the Melbourne Football Club, competing in 244 consecutive games.

After he left football in 1998, he took on the cause of Indigenous players as the AFL’s anti-racism officer, and today is well-known for his work with young people through the Reach Foundation that continues despite his high-profile battle with cancer.

Another successful Irish recruit is Tadhg Kennelly. Tadhg Kennelly famously danced an Irish jig for the television cameras as a member of the winning Sydney Swans team in the 2005 Australian Football League grand final.

Returning to Ireland after the death of his father, he played in the County Kerry team that won the 2009 All Ireland (Gaelic) Football Final, so completing a unique double. He danced a little jig on that occasion too.

The Irish raider

When he was growing up in Ireland, horse trainer Dermot Weld was given a book of Banjo Paterson’s poems. They enthralled him, and within weeks he had memorised many of them: ‘I visualised myself riding the ranges of that open country, rounding up cattle, herding sheep and experiencing heat.'

Years later, Weld astonished a group of Australian journalists who had asked him whether he could recite any of Paterson’s poems that were not about racing by launching into ‘A bush christening’:

On the outer Barcoo where the churches are few,

And men of religion are scanty,

On a road never cross’d ’cept by folk that are lost,

One Michael Magee had a shanty.

On that occasion, at Flemington racecourse on Tuesday 2 November 1993, Weld could afford to indulge his love of Paterson. He was celebrating having just become the trainer of the first overseas-trained horse to take out Australia’s richest and most prestigious race — the Melbourne Cup.

Vintage Crop, trained by Weld in Ireland and owned by Sir Michael Smurfit, ran a great Melbourne Cup in 1993. In the last furlongs, the ‘Irish raider’, as he was dubbed, unleashed a magnificent run from the field to outpace the leaders.

Weld had dreamt of taking out the Cup ever since his first reading of ‘The Man from Snowy River’, and now, like the ‘colt from old Regret’, the Melbourne Cup had ‘got away’ — to Ireland.

Heart of Australian racing: The Melbourne Cup 13 Aug 2010

Welcome to ‘The Heart of Australian Racing: the Melbourne Cup’ symposium

Reconnecting with Ireland

Sister Brenda Browne and the ‘49ers’

County Kerry people remember their own. On 5 July 2010 Kerry Radio reported the passing of centenarian Sister Brenda Browne of Brisbane, Australia.

A Sister of Mercy, she was originally Mary ‘Bidge’ Browne from Ballyhorgan, Ballyduff, County Kerry, who left Ireland for Australia in 1924, aged 19. There she spent the rest of her long life serving the order by teaching in Queensland Catholic schools.

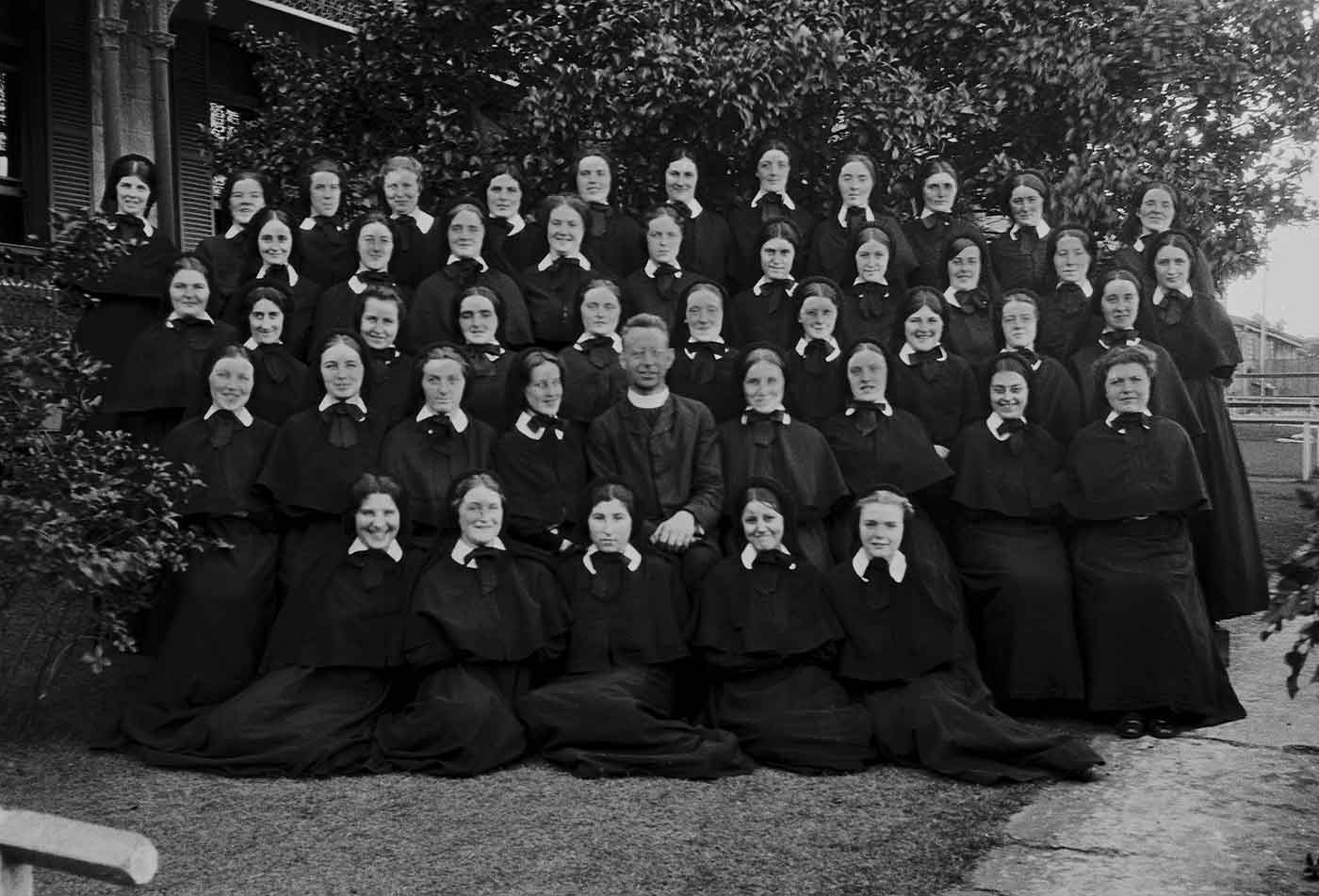

Sister Brenda did not come to Queensland alone. She was part of a group of 49 young novices from Ireland, all offering their lives to the service of God.

The order looked to Ireland as a source of dedicated teachers, nurses and social workers, and the ‘49ers’, as they were known, were just one of many groups who came to Brisbane in the 1920s and 1930s.

In an age before jet travel, few of these young novices expected to see Ireland, or their families, again.

Leaving Ireland in 1947, Sister Angela Doyle, also bound for Brisbane, wrote: ‘We did not dwell too long on the sacrifice that this entailed. We were giving our lives to God and we would do it willingly and as cheerfully as the pain of parting allowed ... As we sailed further from our homeland, we put our faith and trust in God for the future.'

Roses of Tralee

In Ireland there is one television event that is right up there with the major sports finals — the annual Rose of Tralee festival.

The Rose of Tralee festival recalls a famous 19th-century love song. Young women from Ireland, and of Irish descent around the world, contest for the title ‘Rose of Tralee’. The festival is a big event in Tralee, County Kerry, and the final night, when the winner is announced, plays to a huge television audience in Ireland.

In August 2010 it rated as the most watched show of the year on any television channel available in Ireland.

Since its inception in the late 1950s, the ‘Rose’ has had its share of critics, but hosted for over 20 years by Ireland’s most famous television and radio personality, Gay Byrne, the festival has always held centrestage in Ireland.

Byrne sees it as a personality show in which the young female contestants might be anyone’s daughter, sister or niece.

By allowing any young woman of Irish descent worldwide to enter, the festival reaches out like nothing else in Ireland to the huge Irish diaspora in countries like Australia.

To date, three Australians have been crowned the Rose of Tralee: Nyomi Horgan, 1995, Lisa Manning, 2001, and Kathryn Feeney, 2006.

All three women have stressed how participating in the competition, and winning the title, has helped them to reconnect strongly with their Irish origins. Nyomi Horgan says that she discovered ‘resemblances that have survived the generations’ and enjoys the ‘bond that makes us family’.

That’s my language

In June 1975 a man driving down Parramatta Road in Sydney suddenly stopped in the middle of the traffic, got out and started to dance. ‘That’s my language, that’s my music,’ he shouted. He had tuned in to the Turkish program of Australia’s first ethnic radio station, 2EA.

Irishwoman Claire Dunne, foundation director of 2EA Sydney and 3EA Melbourne, which were forerunners of SBS, would recall how Arabic speakers cried to hear the sounds of their own country over the air.

Soon program coordinators were telling her that people from different ethnic groups were writing in to say there was now no need to return to their homeland — ‘Home is Australia’.

Dunne’s support for multicultural Australia arose out of her strong sense of her Irish heritage.

Revisiting Ireland, and reconnecting with Irish music, brought Dunne back to Australia with a growing awareness that it was this music that most strongly expressed Irish cultural identity.

Immigrants, she realised, needed to ‘keep contact with what was foreign to Australia’, for if they lost that, ‘they lost part of themselves’.

In 1999 Dunne was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for ‘service to multiculturalism, particularly through the promotion of Celtic culture, and to ethnic broadcasting’.

John Moriarty’s fishing rod

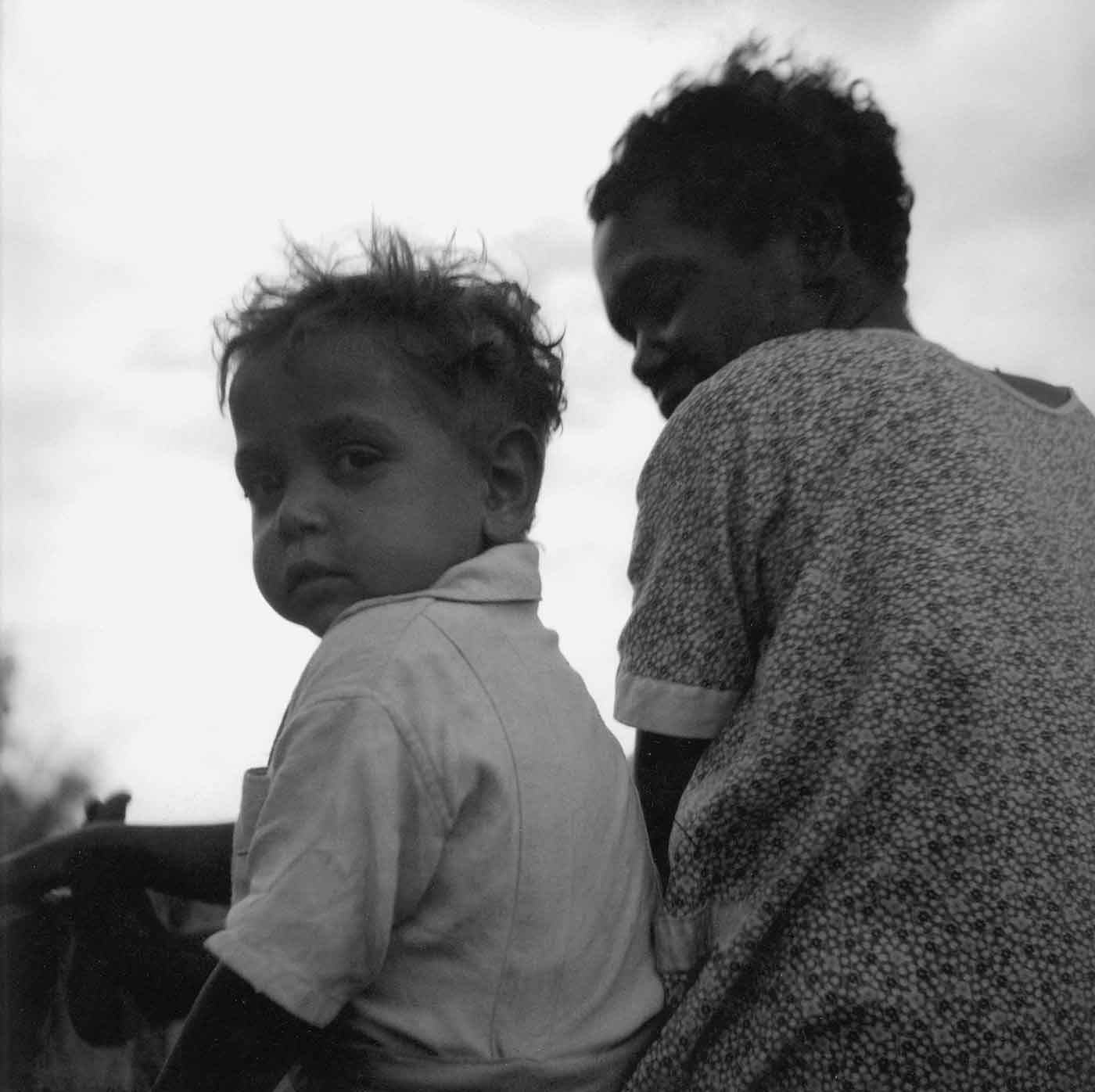

Top sportsman, activist for Indigenous rights, federal public servant, designer and successful businessman — John Moriarty has been all of these. Like many Indigenous Australians he has an Irish surname, indicating his family links with that country.

Moriarty was also one of the Stolen Generation, taken away from his Yanyuwa mother in the Northern Territory when he was four, and brought up in homes and schools in southern Australia.

John Moriarty’s search for the Irish part of his identity took him to County Kerry in 1980, and to a meeting with Pat ‘Aeroplane’ O’Shea. O’Shea, aged 92, had been a star Gaelic footballer for Kerry before the First World War.

After a 20-minute conversation with Moriarty in the doorway, O’Shea asked him in. He told him about a visit by Moriarty’s father in 1928, even remembering how many trout they had caught when they went fishing together.

From the back of a cupboard, O’Shea retrieved an old fishing rod, tied together in three pieces, and a separate brass reel. Apologising for the fact that the line had rotted away, he handed the rod to Moriarty with these words: ‘He left it here for you.'

During his visit to Kerry, Moriarty met many of his Irish relatives for the first time, and found himself readily accepted by them.

When ‘Aeroplane’ O’Shea died, a local paper recalled Moriarty’s visit, confiding how the old family fishing rod was now ‘safe in the hands of the Moriarty clan of Australia’.