The Not Just Ned exhibition developed by the National Museum of Australia features objects that help to tell a story of the Irish building new lives in Australia in fields including politics, religion, education and the arts.

In 1888 Irish-born journalist James Francis Hogan felt that his countrymen and women had created a ‘New Ireland in Australia’. But the truth was much more complex.

Eighty per cent of the Irish emigrants in Australia were Catholic and they faced prejudice for their religious views, support of Irish nationalism and a separate school system.

Stories featured here include that of Eureka leader Peter Lalor, the Kelly gang, the Fenian political prisoners rescued from Fremantle, outspoken archbishop Daniel Mannix, prime minister Ben Chifley and poet Vincent Buckley.

Power and politics

The Eureka stockade

Mark Twain, writer and humorist, 1895:

The finest thing in Australian history ... a strike for liberty, a struggle for principle, a stand against oppression.

The Eureka rebellion came after a long period of protest against the way the Victorian goldfields were being administered. Miners objected to the high cost of mining licences, brutal police ‘licence hunts’, the unrepresentative nature of the colonial government and general corruption.

After a vicious licence hunt on 30 November 1854, tension between the miners and the authorities came to a head. As men gathered to protest, Irishman Peter Lalor came forward to proclaim ‘liberty’.

The next day Lalor led about 500 miners beneath their flag, the Southern Cross, in an oath: ‘We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other, and fight to defend our rights and liberties.' Under Lalor’s command, the rebellion assumed a more Irish feel. He chose the password ‘Vinegar Hill’, recalling the last great battle of the 1798 Rebellion in Ireland.

Just before dawn on 3 December 1854 a force of soldiers and policemen stormed a rough fort on the Ballarat goldfields, known as the Eureka stockade. Inside were about 150 miners, many of them Irish like their leader.

In less than half an hour, the stockade fell. Twenty-seven civilians are thought to have been killed, most in the stockade itself. Lalor himself was wounded at Eureka and lost an arm.

There were many reports of official brutality. Thirteen miners, six of them Irish, were later tried for high treason, but were found not guilty. No Victorian jury would convict them.

The story of the miners’ battle at Eureka quickly entered Australian folklore. In 1891 the Melbourne Cyclorama Company offered the public the story in the round, in the form of a 360-degree panoramic depiction of the Eureka stockade, at its building at Victoria Parade, Melbourne. This surviving image (above) shows the battle at the stockade on the morning of 3 December 1854.

Peter Lalor

Peter Lalor was born in County Laois, Ireland in 1827 and died in Melbourne in 1889. Politically, Lalor was a complex figure. Although he believed strongly in personal liberty, he was neither republican nor socialist.

Lalor emerged to lead the Eureka rebellion and lost an arm after being wounded in the battle. After Eureka, he entered parliament and became a fairly conservative politician.

The Kelly armour

Of all the scenes in Australian history many would argue that none is more dramatic than that of a wounded iron-clad figure emerging out of the mist and advancing towards an inn besieged by police at Glenrowan, in northern Victoria.

It was dawn on 28 June 1880 and outlaw Edward ‘Ned’ Kelly had come to rescue his brother, Dan, and fellow gang member, Steve Hart, who were trapped in the inn.

Inside, another member of the gang, Joe Byrne, already lay dead, killed by police gunfire. All four men were wearing makeshift armour, manufactured secretly in the bush during the previous winter from the mould boards of ploughs.

No results were found

As Ned Kelly lurched forward that morning, the sight unnerved his opponents. Artist Thomas Carrington saw something with ‘no head visible’, more like a ghost than a man, and with a ‘very long thick neck’. Railway guard Jesse Dowsett thought the man with the iron helmet looked ‘nine feet’ (2.7 metres) tall. Others described demons and devils.

Constable George Arthur, however, simply saw some madman on the loose with a nail can on his head. He called out to Kelly that he would be shot if he kept moving, but the outlaw coolly swept back the folds of his oilskin coat and raised the revolver in his right hand. ‘I could shoot you, sonny,’ Kelly warned.

With that, Arthur fired; the bullet struck Ned’s helmet, forcing him back, but he recovered enough to fire. For a while Kelly’s armour protected him. Bleeding profusely from wounds received during the previous night’s run-in with the police, he staggered under the armour’s weight towards the inn, shouting to Steve and Dan, ‘Come out, come out, boys, and we’ll whip the beggars.'

Called on to surrender, Ned yelled back his defiance: ‘Never, while I’ve a shot left.' Eventually, with a despairing cry of ‘I’m done, I’m done’, he was brought down by wounds to his unprotected legs, and captured alive.

After the siege at Glenrowan the police took away all four sets of armour. When a request came to have them displayed at the Beechworth Museum, Captain Frederick Standish, Commissioner of Police, was outraged. He proposed to the government that the suits be destroyed at once to prevent the growth of any ‘Kelly-heroism’.

But they have survived. Seen together they are a striking reminder of one of the most daring challenges to the forces of law and order in Australian history.

Irish nationalism

Escape

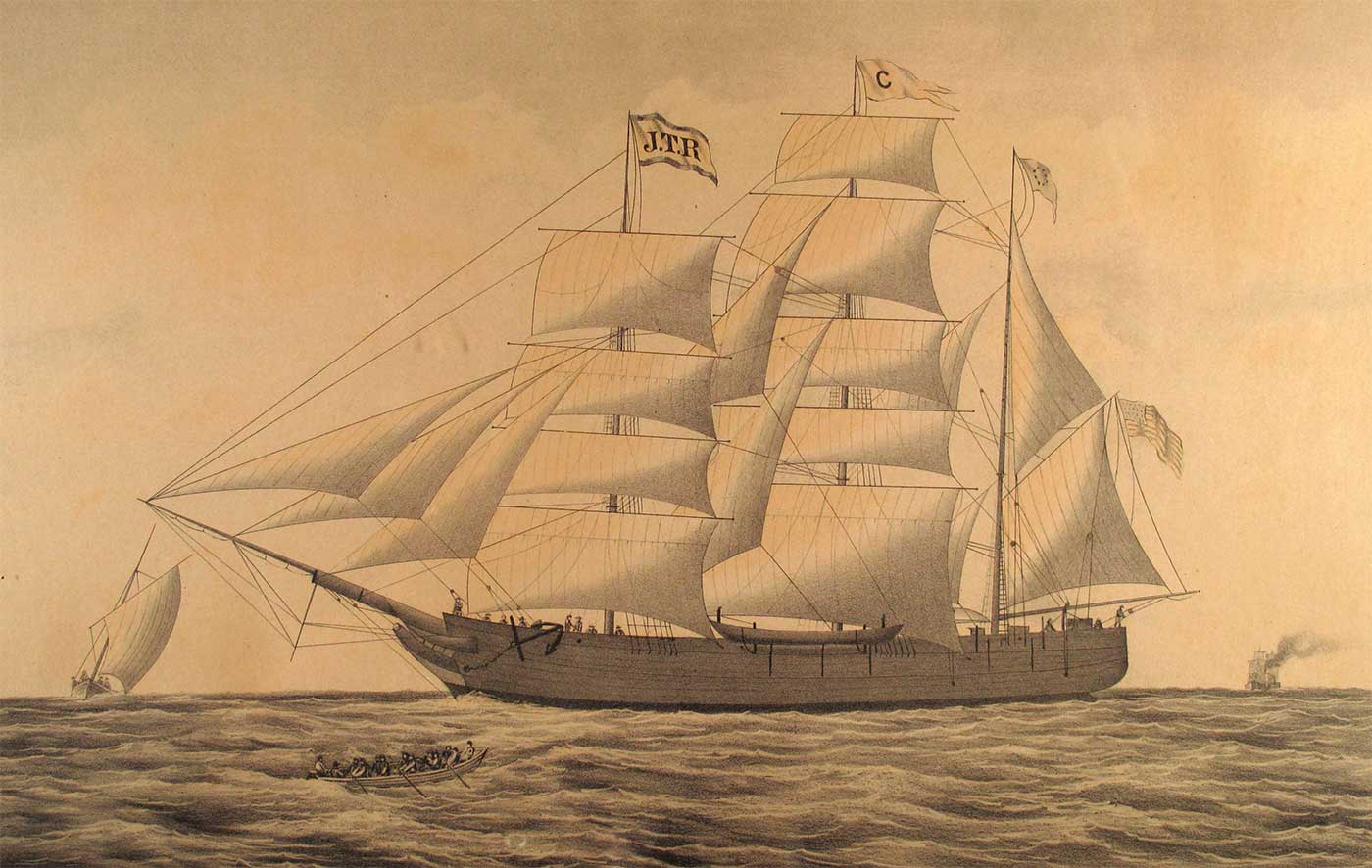

In 1876 the American Fenians organised Australia’s first and last transoceanic prison break by snatching six Irish Fenian rebels from Fremantle Prison and sailing them to freedom in the United States on the American whaler Catalpa.

John T Richardson was a whaling ship agent in the port of New Bedford, Massachusetts, who was approached in 1875 by members of Clan na Gael, an Irish revolutionary organisation, to help them buy a ship and appoint a captain to undertake a voyage to Western Australia. But this was to be no ordinary money-making trip.

The secret aim was to rescue six imprisoned Irish rebels from Fremantle Prison. They were members of the Fenian Brotherhood, who had staged an unsuccessful rebellion in Ireland in 1867.

Richardson’s son-in-law, Captain George S Anthony, had quit the sea for a job in the Morse Twist Drill Works. Restless there, he approached Richardson for a ship, only to be told that he had ‘something better’. Anthony was introduced to John Devoy of Clan na Gael, who offered him a ship and the excitement of a daring rescue.

It must have been a difficult moment for Anthony. He was only recently married with a baby daughter and his mother was ill. Capture would have meant years in prison far from America. But Devoy and others are thought to have awoken in him a ‘personal interest in the men [the Fenians] whose zeal for patriotism had placed them in an unfortunate position’.

Anthony took the job, and he and Richardson bought the whaling ship Catalpa for Clan na Gael. The ship was fitted out for a whaling voyage of 18 months. A mixed crew of Americans and so-called ‘Malays’ (South-East Asian seamen with names like Mopsy Roso and Zempa Malay) were hired.

As the Catalpa set sail for Western Australia, flying from the masthead was the ‘JTR’ (John T Richardson) pennant of the ship’s agent.

The same pennant was flying on 18 April 1876 as six Fenians clambered aboard the Catalpa off the Western Australian coast, south of Fremantle. Picked up from Rockingham Beach, they had spent all night in an open whaleboat commanded by Anthony, having successfully avoided capture by the ships the colonial authorities had sent to look for them.

The pennant was most likely also flying on 24 August as the Catalpa put into New Bedford. It was welcomed by a 70-gun salute and a crowd of thousands who swarmed over the vessel and ‘carried away everything which was not too large for souvenirs’. The pennant survives in the care of Captain Anthony’s descendants to this day.

Irish nationalism

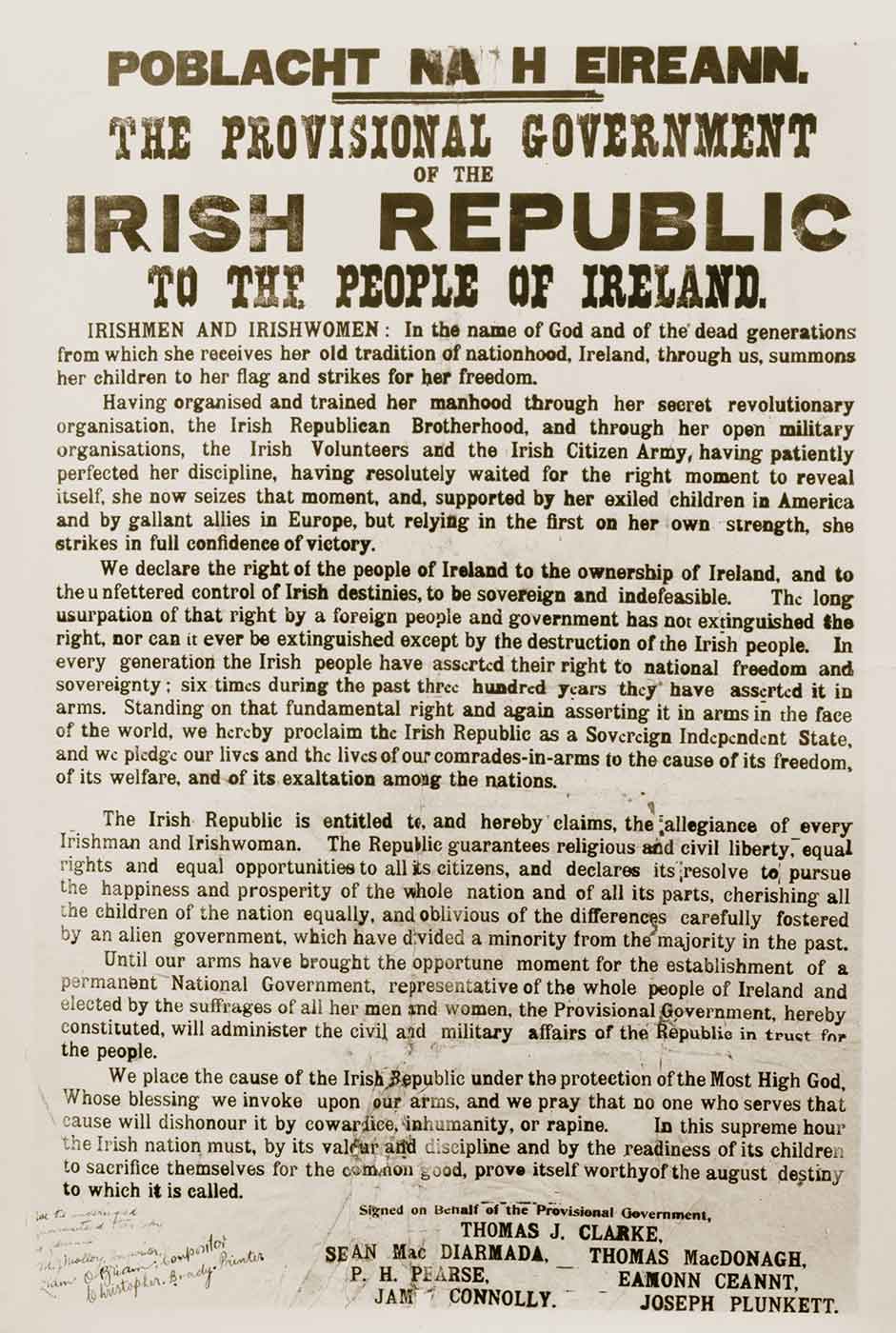

Declarations of independence are dramatic events in any nation’s history. On Easter Monday 1916 Commandant-General Pádraic Pearse of the Army of the Irish Republic, on behalf of the Provisional Government of the Irish Republic, stepped outside the General Post Office in the heart of Dublin and read a proclamation calling the republic into existence: ‘Ireland, through us, summons her children to her flag and strikes for her freedom.'

This act marked the start of the famous Easter Rising. For just over a week rebel forces held out in various locations throughout the city, but the end was inevitable. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was at war, and 16 of the rebel leaders were executed after they surrendered.

Most Irish, and Irish communities throughout the world, condemned the rebellion. The executions, however, sparked sympathy for the rebels and criticism of Britain.

The rebellion and its fate would come to have a profound effect on politics back in Australia. In the second half of 1916 the nation became involved in an often bitter campaign to introduce compulsory conscription for overseas military service.

Until then, recruitment had been voluntary, but the large losses of men in France convinced Prime Minister William Morris Hughes that conscription was essential. However, in two referendums — held in October 1916 and December 1917 — the Australian people narrowly rejected conscription.

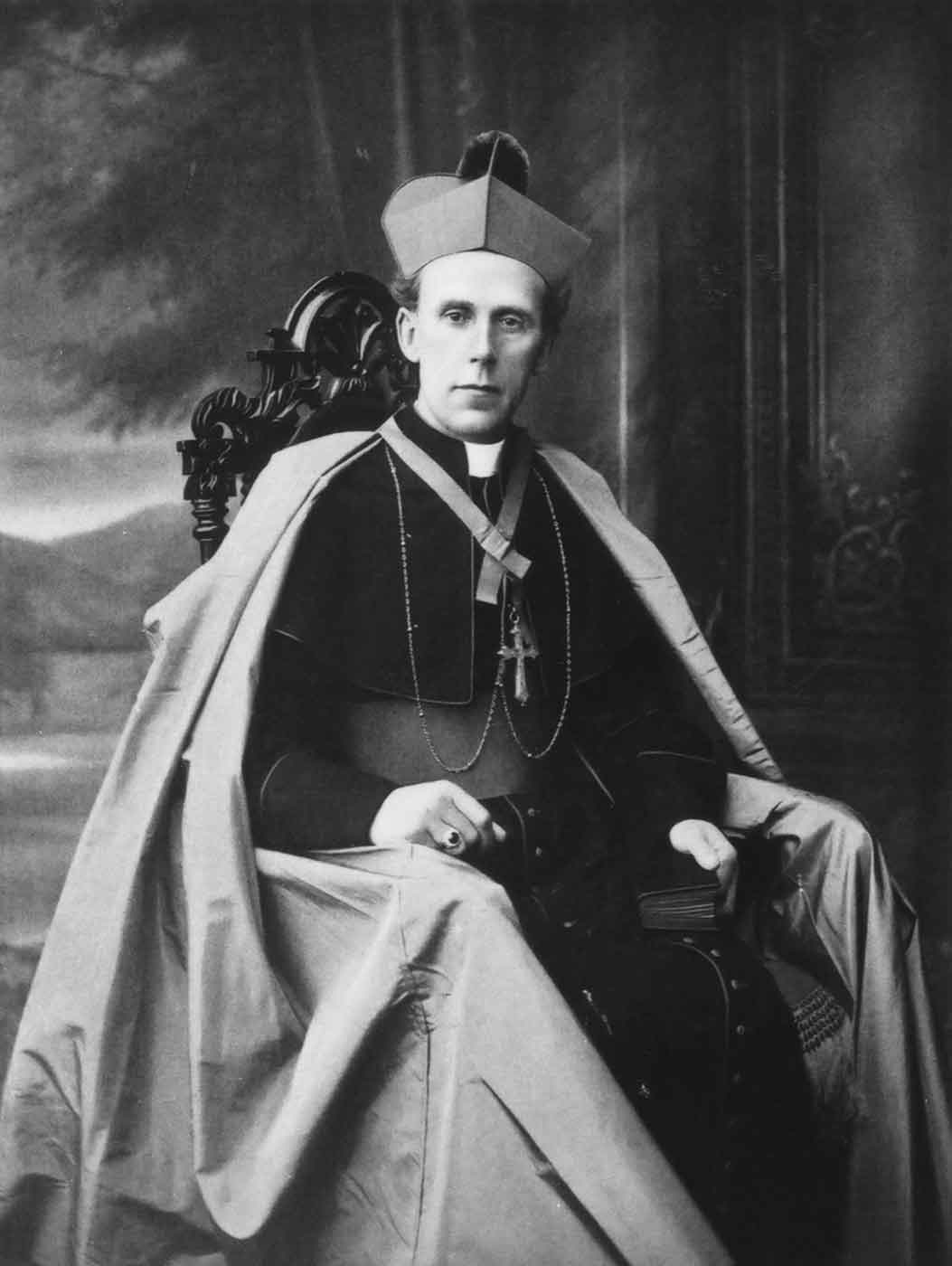

Opposing Hughes over conscription was the Irish Archbishop Daniel Mannix. After the Easter Rising Mannix increasingly took up the cause of an Irish republic, and in Australia he became one of the most prominent anti-conscription leaders.

Hughes accused Mannix and others who opposed him of being virtual traitors to Australia and to the Empire in its hour of need. Mannix fought back by declaring that Catholics were loyal to Australia, but that did not mean they automatically accepted British rule in Ireland.

The level of division and bitterness in the Australian community was one rarely experienced before or since. St Patrick’s Day processions in Melbourne, led by Mannix, took on the appearance of Irish national demonstrations with floats depicting the ‘martyrs of 1916’.

In March 1918 it became an offence to advocate the independence of Ireland, and a number of Irish Australians were imprisoned. The uproar died away after a treaty was signed between Irish and British leaders in December 1921. It gave Ireland independence within the British Empire, but withheld republican status.

For his part, Mannix remained the Australian champion of complete Irish republican independence for the rest of his long life.

Religion

Rebel bishop

Catholic archbishop of Melbourne, Daniel Mannix, was born in County Cork and came to Australia in 1913.

During the First World War he became famous for his opposition to conscription for overseas military service. It was a bitterly divisive issue and he and his supporters — and Irish-Australians in general — were accused of disloyalty to the nation and the Empire.

Mannix’s opposition to conscription hardened after the execution of 16 rebel leaders during the 1916 Easter Rising against British rule in Ireland.

Mannix is probably the only Australian bishop ever to be arrested at sea. Fearful that he might make inflammatory anti-British speeches in Ireland, British detectives removed Mannix from the liner bringing him across the Atlantic in August 1920.

Forced to land in England, Mannix was forbidden to visit cities with large Irish populations. Mannix was given the freedom of the city of Dublin in 1925.

In 1939 Archbishop Daniel Mannix oversaw the completion of the spires of St Patrick’s Cathedral in Melbourne. That same year he gave a plaster of Paris model of St Patrick’s, made by monumental mason James McGowan, to the Public Library and Museum of Victoria.

A model cathedral

Hailed at its official dedication and opening in October 1897 as the ‘greatest ecclesiastical edifice in Australia’, St Patrick’s Cathedral, Melbourne, had already been on show to Victorians for years. The Melbourne International Exhibition of 1880 featured a plaster of Paris model of St Patrick’s made by monumental mason James McGowan.

After the exhibition closed in March 1881, McGowan presented it to the Catholic Church. The model showed donors to Archbishop Thomas Carr’s cathedral fund what their money was helping to build.

In 1939 Archbishop Daniel Mannix oversaw the completion of the cathedral spires. That same year he gave McGowan’s model to the Public Library and Museum of Victoria.

Why give it away? Perhaps because the model reflected architect William Wardell’s original ideas for the spires, and Mannix had ensured they were built to a height greater than originally planned.

He wanted them to tower above the eastern end of the city, supposedly above the Parliament of Victoria. McGowan’s model had become the vision of another time and so was relegated to a museum.

Today, however, it has come back to St Patrick’s, where it is displayed as a tribute to that generation of Irish Catholic immigrants, and their Australian children, who gave their shillings and pence to build it.

The Cross of Cong

One of the great moments of any ceremony in a Catholic cathedral comes when a cardinal, fully clothed in his red robes, processes to the altar with his attendant priests, amid swirls of incense. Australia’s first cardinal was Irishman Patrick Francis Moran, appointed in 1885.

Moran was determined to show Australian Catholics of Irish descent their cultural inheritance, the rich iconography of the early Christian church in Ireland. One of the objects he brought out from Ireland was a full-sized replica of the Cross of Cong, which was carried before him as he strode to the altar.

The original Cross of Cong, a 12th-century Irish Christian processional cross, beautifully worked with Celtic designs in gold and silver, was made to house a relic of the cross of Christ.

It was hidden away in the mid-17th century, rediscovered in the 17th century and ended up in the National Museum of Ireland, where it is regarded as one of the museum’s greatest treasures.

A replica was made by Dublin jeweller Edmund Johnson for the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, and copies were made by Tiffany’s of New York. Moran brought one of these fine replicas to Sydney, where it testified to the antiquity and splendour of Australia’s Irish-dominated Catholic Church.

Monstrance

In the Catholic church a monstrance is a most religious and highly significant vessel. It is used to display to the faithful a piece of consecrated bread, known as the Blessed Sacrament, which Catholics believe has become the real body of Christ during the mass.

On special feast days, such as Corpus Christi (Body of Christ), a large and highly decorated monstrance might be used to carry the Blessed Sacrament in procession around the parish.

This monstrance was made from jewellery donated by Brisbane Catholics. Betty Dolan of the Parish of St Augustine’s, Coolangatta, Queensland, remembers Corpus Christi in the 1940s and 1950s being attended by the Brisbane diocese’s Irish-born archbishop, James Duhig: ‘Parishioners, sodality members, and visitors would assemble in procession from the church on McLean Street, led by cross bearer Keith Farrell and the clergy, [and] Archbishop Duhig ... carrying the monstrance under a canopy.'

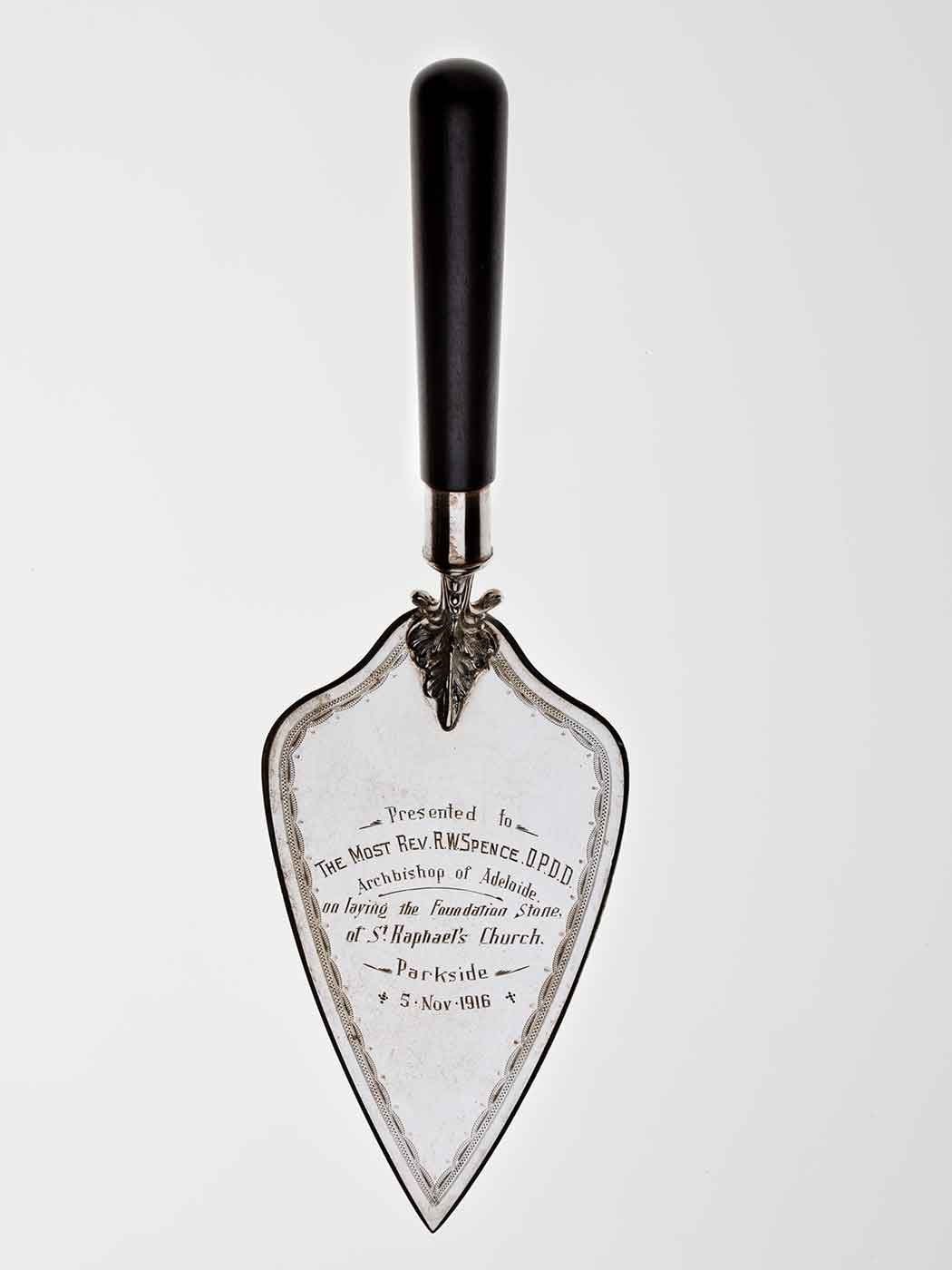

Spence the Builder

Australian Catholics were used to opening their wallets to help their church. Over the decades they donated a sizeable sum towards the building of churches, presbyteries, church halls, catholic schools, convents and monasteries.

Such buildings are dotted across Australia, from city centres to suburbs, country towns and smaller rural settlements, and constitute the most visible legacy of the Irish Catholic presence.

South Australia was always regarded as the least Irish and Catholic of the Australian colonies. Nevertheless, during the reign of Irishman Robert William Spence as Catholic archbishop of Adelaide, his diocese experienced a veritable building boom.

Spence officiated at the laying of foundation stones, and the opening of more than 85 major church buildings. The man who became known as ‘Spence the Builder’ was proud of this achievement because, as he saw it, thousands of ordinary Catholics had contributed to the expansion of their church.

Spence had the many silver trowels he used on these occasions mounted onto shields for display at his official residence.

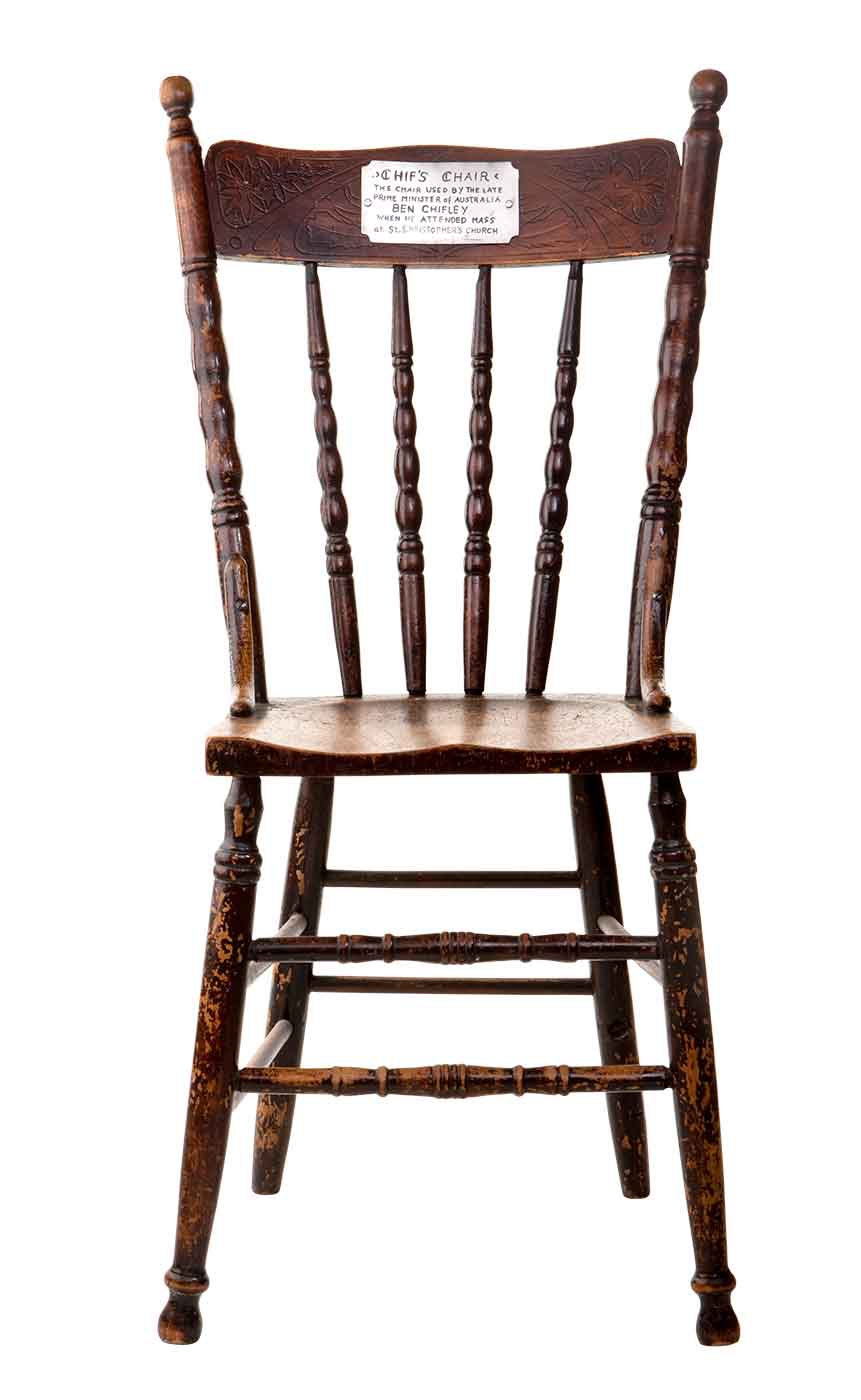

Chif’s chair

The Catholic church has traditionally disapproved of marriages between Catholics and non-Catholics. In 1908 the Pope announced the famous ‘Ne Temere’ decree, which ruled all marriages between Catholics and others invalid unless conducted by a Catholic priest.

This decree affected the relationship between Ben Chifley and Elizabeth McKenzie of Bathurst, New South Wales. Chifley was Irish Catholic on all sides of his family, and McKenzie was a Presbyterian with Scottish parents, who were definitely not in favour of her converting to Catholicism in order to marry Chifley.

And so in June 1914 they married in a Presbyterian church, Chifley taking the view that ‘one of us has to take the knock. It had better be me’.

The ‘knock’ for him meant that for having married outside his church he was barred from taking communion, and the church did not regard his marriage as legitimate, even though it was legal.

The Chifleys would simply have been another couple whose lives were complicated by a mixed marriage but for the fact that theirs were lived in the spotlight of public attention. Chifley was a leading Labor politician and, on Prime Minister John Curtin’s death in 1945, he became prime minister of Australia.

He never deserted his church. When in Canberra he often attended mass at St Christopher’s Catholic Church, now St Christopher’s Cathedral, where he sat in the back of the church on what is now preserved there as ‘Chif’s chair’.

When Chifley died in 1951 he was given a Catholic funeral in Bathurst.

Education

An orrery from Ireland

It is difficult now to catch that tone of condescension, superiority and often outright racism with which the Irish, especially the Catholic Irish, were once confronted in the Australian colonies. Jokes and cartoons ridiculing supposed Irish stupidity, illiteracy and general racial inferiority were commonplace in magazines such as the Sydney and Melbourne editions of Punch.

So it is hardly surprising that the Catholic Irish worked hard to give their children an education that would allow them to get on — and move up — in colonial society.

For their daughters, those who were better off turned to the Irish nuns. By the 1880s and 1890s quality teaching and facilities could be found in such schools as Loreto College, Mary’s Mount, Ballarat, Victoria.

The founder of the college, and its first principal, was Irishwoman Mother Mary Gonzaga Barry of the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary, better known as the Loreto Sisters. She had a simple message for her pupils: ‘Set before yourself something which will ennoble your life, your thoughts and your endeavours. Aim at something excellent.'

For her day, Mother Barry had an extremely advanced approach to girls’ education. The Loreto curriculum encompassed, among much else, literature, mathematics, languages, music, painting, science and history.

The school even possessed an orrery, a mechanical model of the solar system, which they used to teach the basics of astronomy. This rare device — there were only three in Australia at the time — was sent out from Ireland by Mother Barry’s brother.

Literature

Searching for Ireland

Australian poet and academic Vincent Buckley was born in 1925 in a cottage behind his uncle’s pub, in a region north of Melbourne much settled by the Irish in the mid-19th century.

He described his Condon, Scanlan and Buckley ancestors as being ‘typical’ and ‘anonymous’, their sense of being Irish having been lost in becoming Australian. This, Buckley believed, was contrary to popular belief that saw Catholics in Australia as having preserved a strong awareness of their Irish origins.

Perhaps it was this sense of disconnectedness with his Irish past that led Buckley into an ever-deepening search for that part of him that was ‘Irish’.

His frequent visits to Ireland naturally took him to sites such as the ancient tower in County Galway associated with William Butler Yeats, Ireland’s most famous 20th-century poet.

Yeats also struggled with what it meant to be Irish, but Buckley seems to have become somewhat disillusioned with the Ireland of the 1970s. Interestingly, in one of his last published poems, he circles back pensively to his Australian birthplace, Romsey:

I see Romsey through a hole in the wind,

as I used to in late autumn, in the southern gales ...

I smell the printer’s ink, and books,

and dust that flashes when the raindrops hit it as it takes the rain into itself.

Michael Dwyer

Irishman Michael Dwyer was one of the rebels from the 1798 Rebellion who was exiled to Australia. Known as the ‘Wicklow Chief’, Dwyer had great support among the ordinary people of County Wicklow.

Despite many forceful house-to-house searches in the area, and the harassment of his relatives, he was never betrayed. He surrendered himself to magistrate William Hume in December 1803.

Despite his enthusiastic involvement in the armed rebellion, once he had served his sentence in Australia, Dwyer became a police constable. He never returned to Ireland.

Dwyer is buried with his wife, Mary, underneath the 1798 Memorial at Wavereley Cemetery in Sydney.