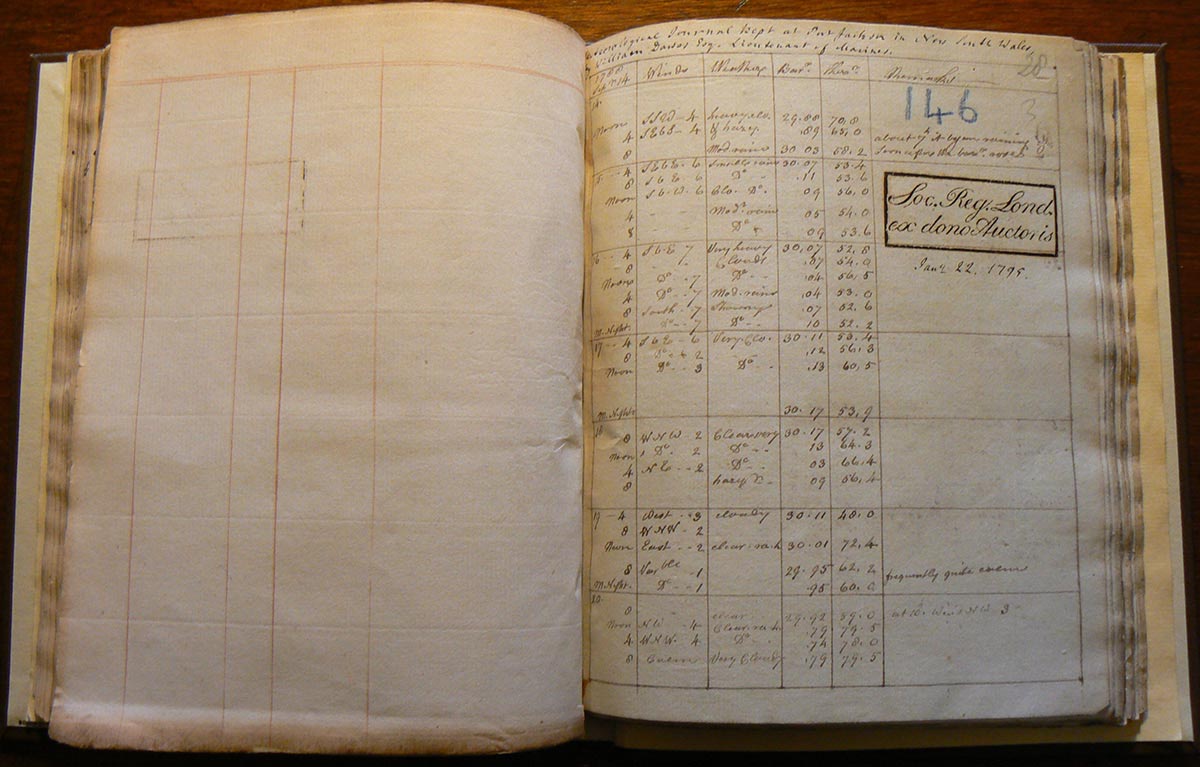

Meteorological records for Port Jackson, New South Wales

The Royal Society had a critical role in the establishment of the first European colony on the Australian continent's east coast. Included in the exhibition were the meteorological records for Port Jackson, New South Wales, 1788–91, kept by Lieutenant William Dawes in the earliest days of the colonial experiment.

The journal is 115 pages long and details the date, wind, weather, barometer and thermometer readings for the fledgling colony. It also records, under the title 'Remarks', rainfall events, thunder and hail. Dawes took up to six readings per day: at sunrise, 8am, noon, 3pm, sunset and 9pm. He also recorded the reliability (or otherwise) of his instruments.

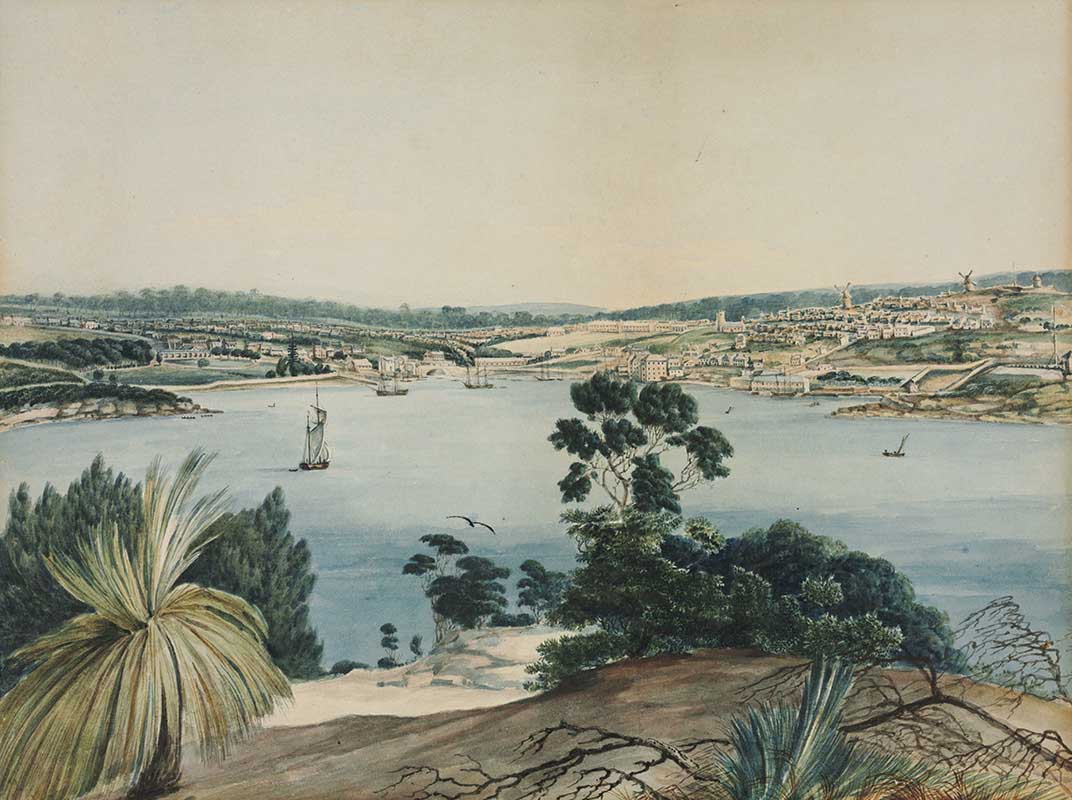

The picture Dawes' journal gives of the weather in Sydney over 200 years ago is particularly significant in light of how climate change has become a topic of such pressing concern today. Dawes' great interest was astronomy, although he also created valuable Aboriginal word lists with the help of the local people he met and befriended.

He set up an observatory on what is now Dawes Point, and was able to establish the longitude of Port Jackson. However, he was constantly called away from his scientific pursuits by the Governor, who needed him to survey plots of land and roads in the colony.

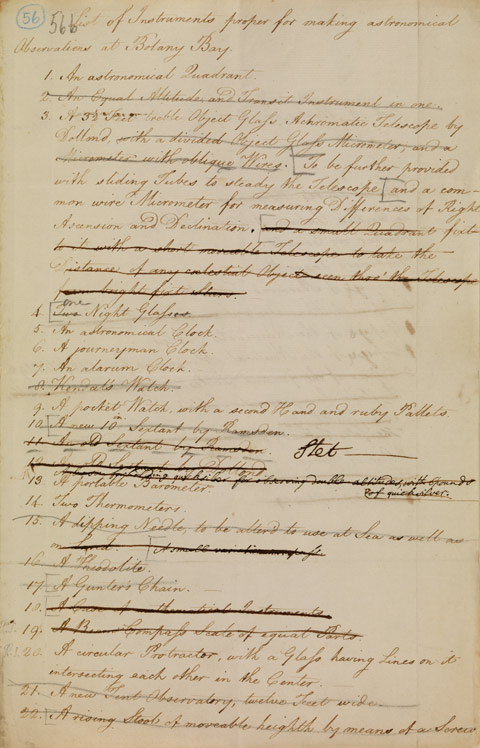

List of Instruments proper for making astronomical Observations at Botany Bay

Other related items include two lists that detail the instruments Dawes needed for his colonial observatory. 'List of Instruments proper for making astronomical Observations at Botany Bay' contains a great many items, but as the Board of Longitude – of which Banks was an ex-officio member by virtue of his position as President of the Royal Society – did not have sufficient instruments on hand, most of these were eventually crossed out.

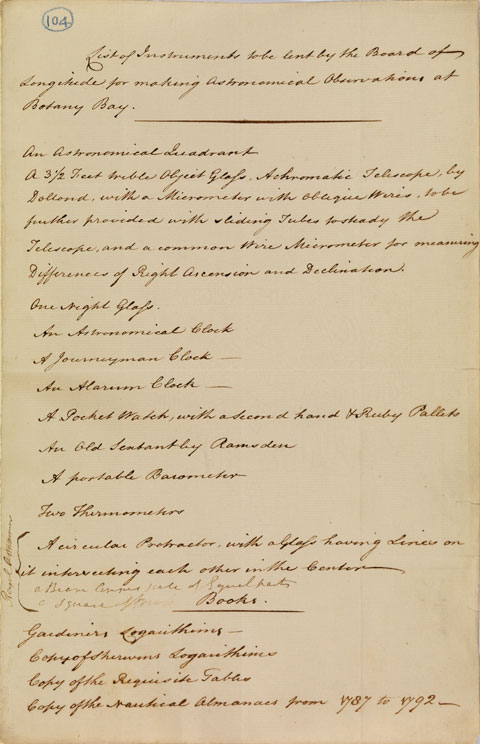

The 'List of instruments to be lent by the Board of Longitude for making astronomical Observations at Botany Bay' is a much shorter list; it served as a clean copy of what was actually available from the Board of Longitude.

Click on the images below for larger view and transcripts.

List of Instruments proper for making Astronomical Observations at Botany Bay (extract):

A 3 ½ feet treble Object Glass Achromatic Telescope by Dollond ... To be further provided with sliding tubes to steady the Telescope ... and a common wire Micrometer for measuring Differences of Right Ascension and Declination.

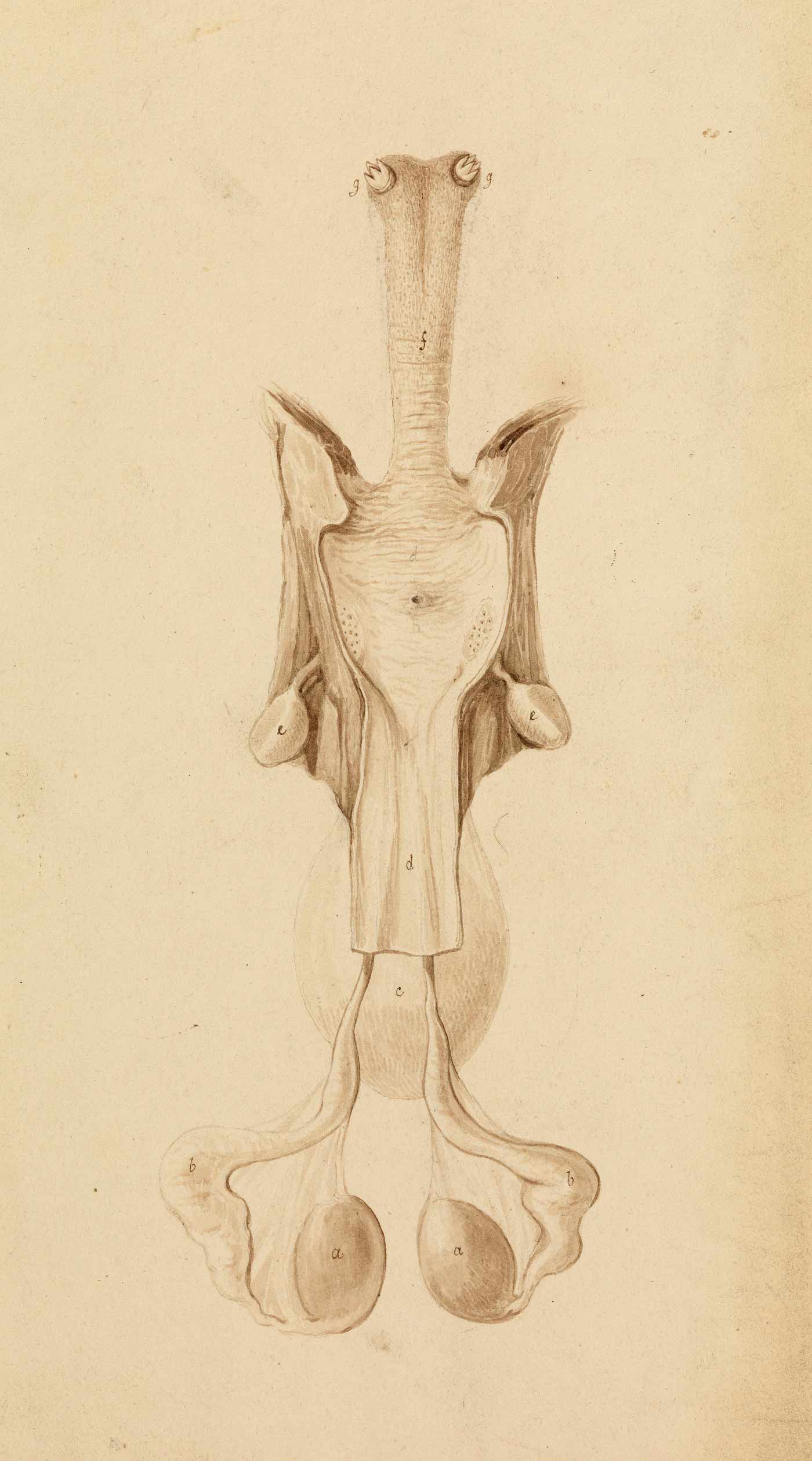

Description of the anatomy of the Ornithorhynchus paradoxus [platypus]

Also included in this section was the ‘Description of the anatomy of the "Ornithorhynchus paradoxus" [the original scientific name for the platypus]'.

Handwritten by Sir Everard Home, the paper comprises 38 pages of text and illustrations describing male and female specimens of the platypus. Home's description of the creature's anatomy was presented to the Royal Society on 17 December 1801.

In the document, Home thanks Sir Joseph Banks for providing access to his specimens and quotes from Governor John Hunter's eyewitness descriptions of platypus behaviour in the wild. The paper examines the platypus's external features as well as its internal organs and structure.

Home constantly compares the platypus with other mammals, birds and lizards, and concludes that, based on their form, the platypus's reproductive organs most closely resemble those of the dog fish, a type of shark: 'In the ovi-viviparous dog-fish, the internal organs of the female have a very similar structure. There is therefore every reason to believe, that this animal also is ovi-viviparous in its mode of generation.'

Home's paper was published in volume 92 of the Philosophical Transactions, at a time when many considered the platypus to be a hoax and the category of monotreme had yet to be proposed.

In 1800 Banks learned of a proposed French expedition to Australia when he was approached about the possibility of securing a scientific passport for the French ships, despite France and Britain being then at war. That the Republic of Letters should have no boundaries was an article of faith for both the Royal Society and the French Académie des Sciences.

This noble point of view did not, however, stop Banks from promoting a rival British expedition to Australia, to be led by Flinders, to pre-empt any possibility of French territorial claims.

As it happened, Flinders met the French ships at Encounter Bay, on the coast of what is now South Australia, in April 1802. Baudin was dismayed to find that Flinders had already mapped the coastline to the east, thereby claiming for Britain the prestige of first discovery.

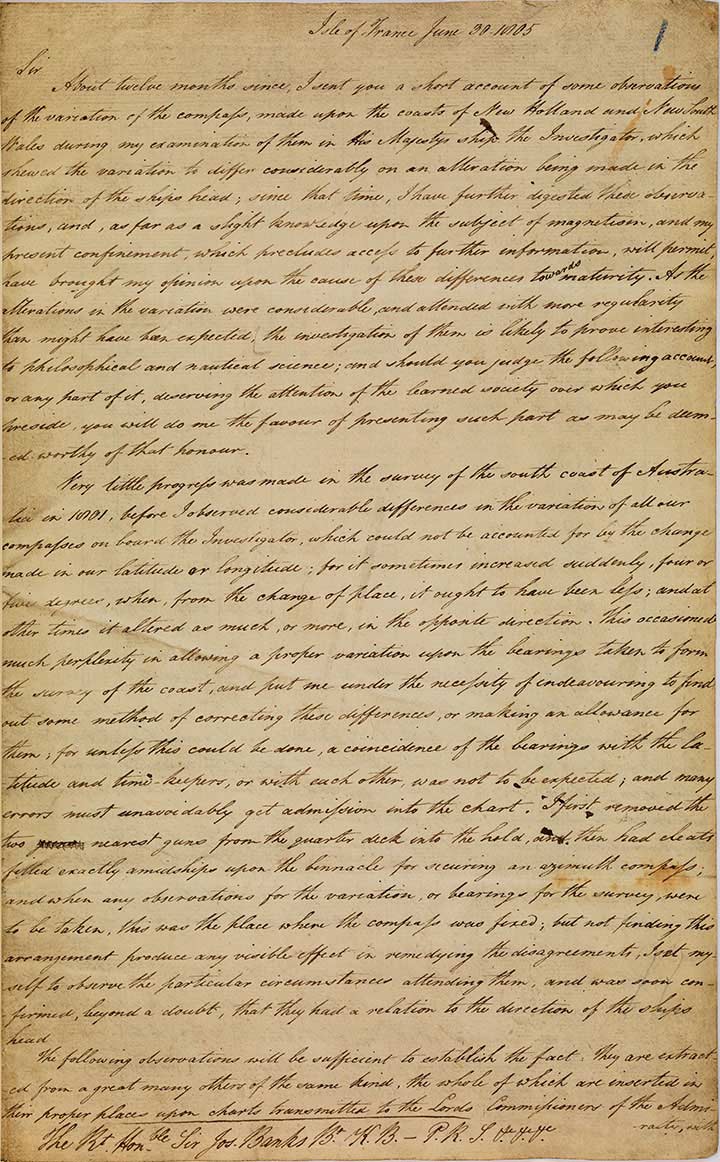

Letter from Matthew Flinders to Sir Joseph Banks

The last Royal Society artefact in this section was a 20-page letter, titled 'On some variations of the compass encountered during the survey of the South Coast of Australia', written by the explorer Matthew Flinders to Banks and dated 30 June 1805.

In mid-December 1803 Flinders had been imprisoned by the French on Mauritius while sailing home from his circumnavigation of the Australian continent.

Two weeks into his 7-year incarceration, Flinders' papers and observations were returned to him and he resumed work on the troubling phenomenon of compass variation.

Variation of the compass had been observed for centuries: it is where magnetic north, as shown by the compass, differs from true north, as shown by the position of the pole star or the midday sun.

The degree of variation depended on location and changed over time, and Edmund Halley produced A General Chart of the Variation of the Compass in 1701 in the hope that charting the lines of magnetic force might assist with navigation or even offer a guide to longitude.

Flinders conveyed these findings to Banks in a letter written on 3 March 1804 and read to the Royal Society a year later. On 5 July 1805 he sent the letter displayed in the exhibition to Banks; it contained his further thoughts on compass deviation and was intended to supersede his earlier letter.

In April–May 1812 following his return to England, Flinders was given permission by the Admiralty to conduct controlled experiments in harbour to confirm his observations. Refined still further, his observations, conclusions and recommendations were published in A Voyage to Terra Australis in 1814.

Flinders' letter reminds us of the role the Royal Society continued to play in promoting voyages of discovery against a background of imperial rivalry between France and Britain.

The many compass readings Flinders had taken while surveying the Australian coastline also revealed another type of variation, one arising from the interaction between the iron contained within a ship and the Earth's magnetic field, and known these days as compass deviation.

Commented on by astronomer William Wales during Cook's second voyage, compass deviation varies according to a ship's path, and it was Flinders who first suggested a cause, quantified the degree of error with a mathematical law, and discovered that an iron bar placed vertically near the compass helped overcome this deviation. Flinders' bar is still used today in binnacles (the receptacles for ships' compasses).

References

Philosophical Transactions, vol. 92, 1802, pp. 67–84.

You may also like