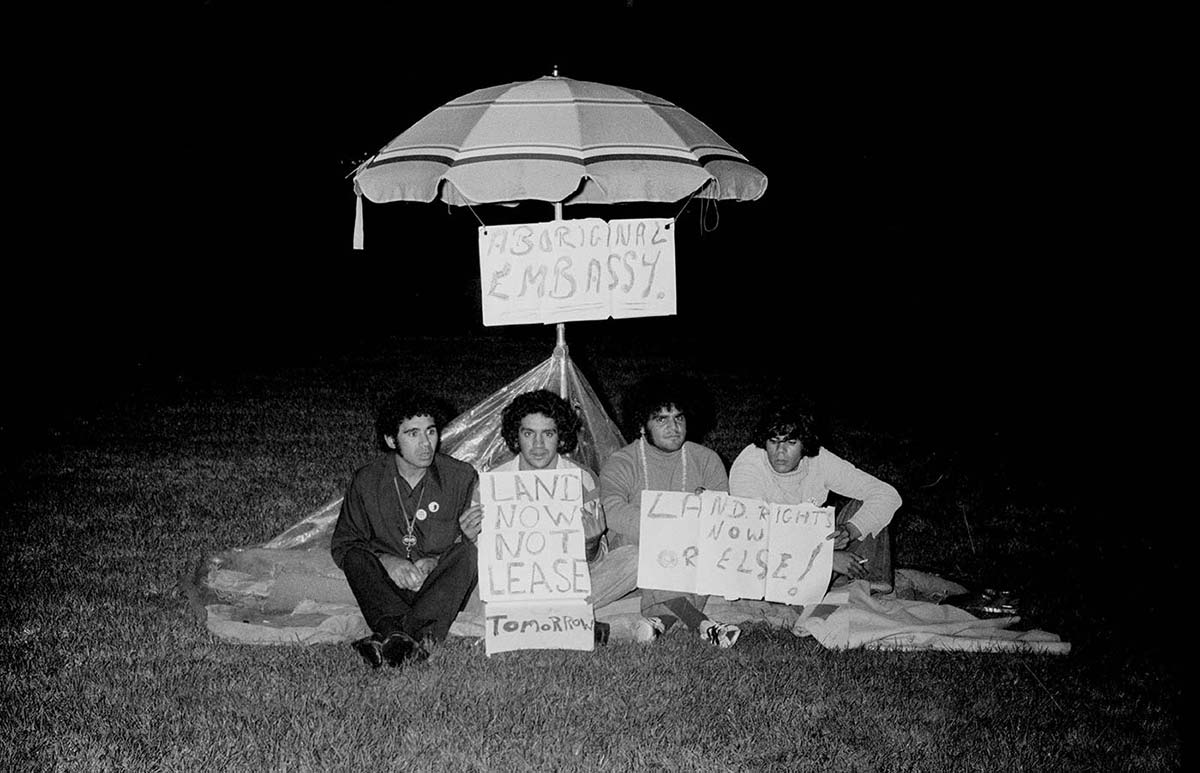

On 26 January 1972, four First Nations men set up a beach umbrella on the lawns opposite Parliament House in Canberra. Describing the umbrella as the ‘Aboriginal Embassy’, the men were protesting against the McMahon government’s approach to Indigenous land rights.

The embassy operated in several locations and took many forms before its permanent establishment on those same lawns in 1992.

The goals of the protesters have changed over time and now include not only land rights but also First Nations sovereignty and self-determination.

John Newfong, Identity, 1972:

With its flags fluttering proudly in the breeze, the Aboriginal Embassy on the lawns opposite Federal Parliament has been one of the most successful press and parliamentary lobbies in Australian political history.

Land rights struggle

First Nations people have been fighting to retain the rights to their traditional lands since British colonisation of the Australian continent. The 1960s and 70s was a period of greater national awareness of Indigenous activism, with significant actions taken by groups in the land rights struggle.

In 1966, about 200 Gurindji stockmen, domestic workers and their families walked off Wave Hill Station, beginning a strike that would last 9 years. Lobbying the Northern Territory and Australian governments for equal pay and conditions, as well as land ownership, the Gurindji people brought these issues firmly into the public eye.

The 1967 referendum also provided more momentum to the land rights struggle by raising the profile of First Nations issues with the wider Australian public.

The 1971 Milirrpum v Nabalco Northern Territory Supreme Court case further highlighted the issue of land rights. In 1963, after traditional lands of the Yolŋu in Arnhem Land were sold without consultation to bauxite mining company Nabalco, traditional owners made several attempts to have the land returned. This included the Yirrkala bark petitions sent to Federal Parliament.

When Justice Blackburn ruled against the Yolŋu on the grounds that native title was not part of Australian law, First Nations communities across Australia were outraged.

Announcement on Australia Day eve

On the eve of Australia Day 1972, Prime Minister William McMahon announced the implementation of a new system that rejected granting independent ownership of traditional land to First Nations people in favour of 50-year general purpose leases. These leases required First Nations communities to demonstrate a social and economic use for the land and excluded any mineral and forest rights.

After the ongoing disappointments of the land rights struggle, this announcement sparked action among many First Nations groups and directly contributed to the founding of the tent embassy.

Beginnings of the tent embassy

After the McMahon government’s announcement, many protesters sprang into action, including a group from Redfern in Sydney. Four members of this group – Michael Anderson, Billy Craigie, Bertie Williams and Tony Coorey – drove to Canberra and set up a beach umbrella on the lawns opposite (what is now Old) Parliament House.

Labelled the ‘Aboriginal Embassy’, the sit-in protest was a symbolic response to Mr McMahon’s statement. As activist Gary Foley remarked, the announcement positioned First Nations people as, ‘aliens in our own land, so like other aliens, we needed an embassy’.

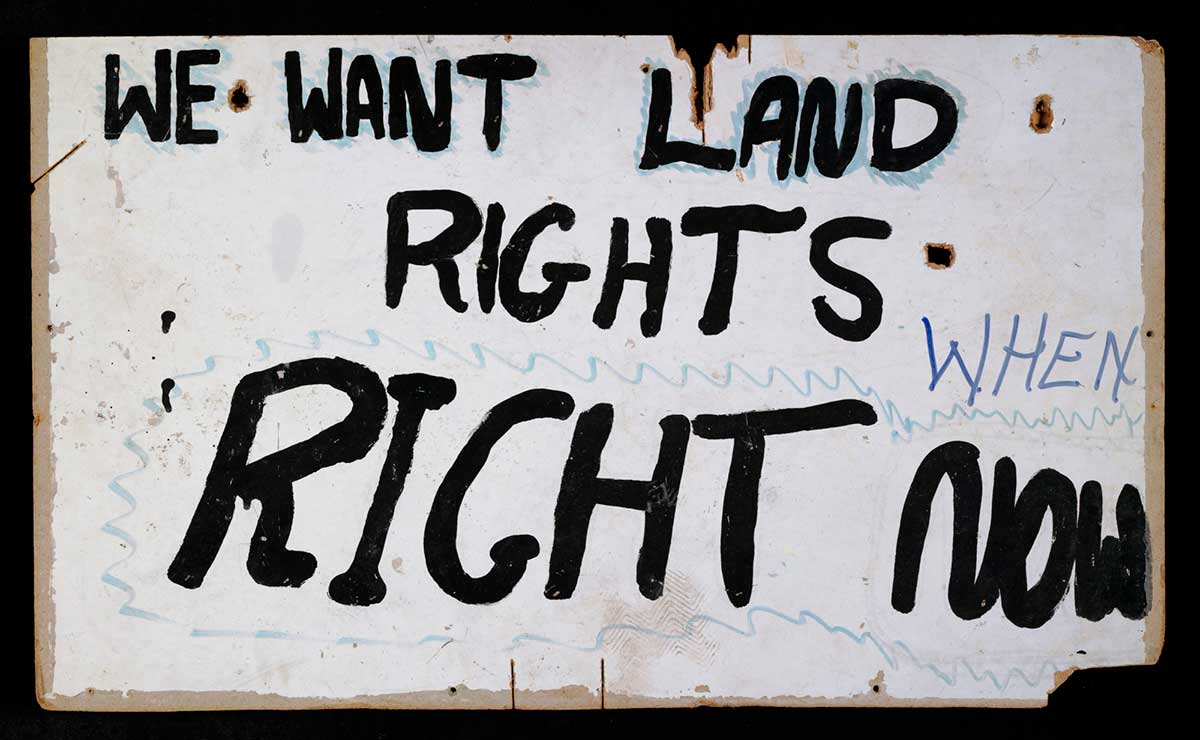

On 6 February 1972 the embassy issued a list of demands to the Australian Government. The list focused on land rights issues and demanded:

- Complete rights to the Northern Territory as a state within Australia and the installation of a primarily Aboriginal State Parliament. These rights would include all mining rights to the land.

- Ownership and mining rights of all other Aboriginal reserve lands in Australia.

- The preservation of all sacred sites in Australia.

- Ownership of areas in major cities, including the mining rights.

- Compensation for lands that were not able to be returned starting with $6 billion and including a percentage of the gross national income every year.

A visit from Opposition Leader Gough Whitlam to discuss the five-point plan was seen by activists as a great success in gaining recognition for their cause and having their ideas heard by those in positions of power.

Growing support for the embassy

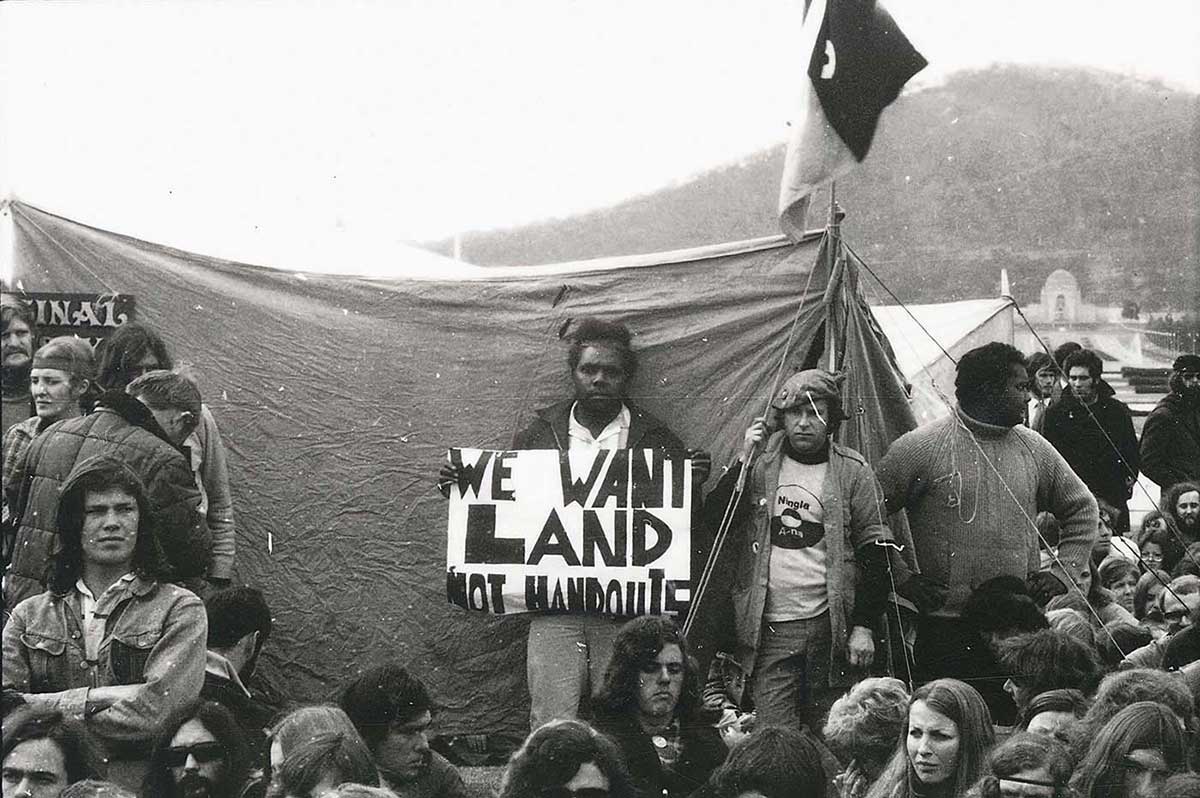

Rapidly gathering support, the embassy grew by April 1972 to include at least six tents. It attracted both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people from across the country, who joined in solidarity over the land rights movement.

Support shown by official representatives from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups, as well as diplomats from countries including Canada and Russia, helped bolster the profile of the embassy.

Canberra's student population were also strong supporters of the embassy. Some Australian National University students joined the protest crowd and helped billet protesters.

Gaining media attention across Australia and internationally, the embassy became a centre for protest. Well-known First Nations activists including Gary Foley, John Newfong, Chicka Dixon and Gordon Briscoe spent time at the site.

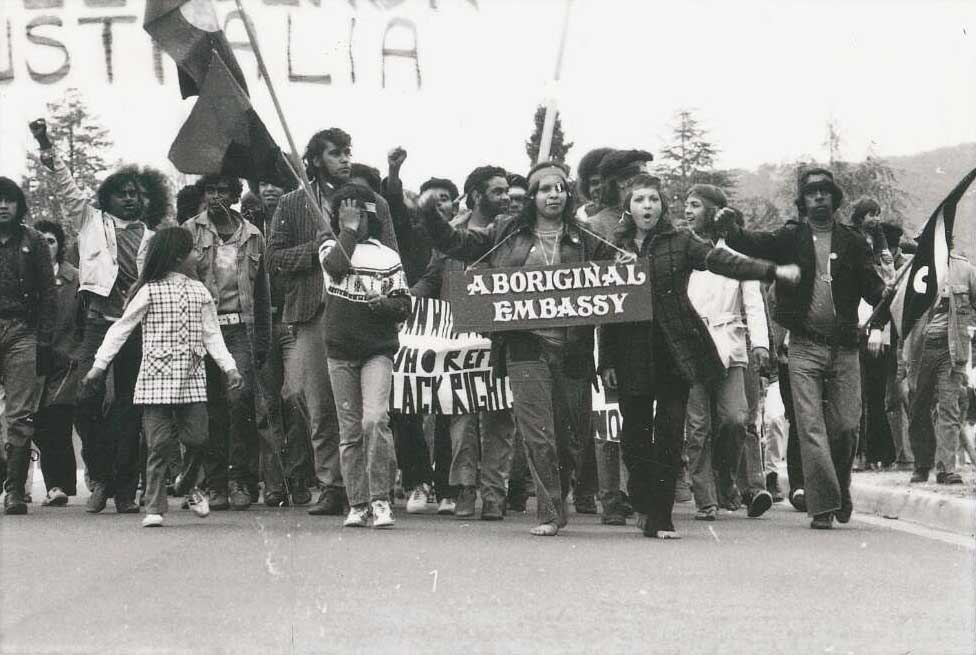

Groups from the embassy went on protest marches, lobbied government representatives and spoke at community forums to continue to raise the issue of land rights in broader public settings.

While the embassy enjoyed support, it also faced a large contingent of politicians and members of the public who believed the protesters were trespassing and the tents were an eyesore.

Offers were made to the embassy for buildings and a ‘club’ to replace the tents, both on the original site and at other Canberra locations. However, these offers were refused as they were seen as a way of placating and removing protesters while making no real changes to the land rights situation.

Police and protesters clash in Canberra

In May 1972 Ralph Hunt, then Minister for the Interior, announced that new laws would come into effect making it illegal to camp on unleased land in the Australian Capital Territory and giving the government powers to forcibly remove anyone found to be in breach of the ordinance.

On 20 July 1972 hundreds of protesters clashed with police in a violent brawl after officers tried to move people along and dismantle the embassy tents. Eight protesters were arrested and the tents were torn down.

The next Sunday, after the tents had been re-erected, more than 200 protesters again clashed with police and the tents were removed for a second time. Media images of police violence against protesters led to even greater support for the embassy and its aims.

On 31 July 1972 more than 2,000 people were present when the tents were re-erected and then removed by protesters in a peaceful demonstration. After Justice Blackburn found the legality of the ordinance giving police power to remove protesters was invalid, protesters again peacefully erected and removed the tents in a symbolic gesture.

The removal ordinance was then legally introduced in September 1972, preventing the re-establishment of tents at Parliament House.

Temporary embassy locations

Between 1972 and 1992 the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was set up at various places across Canberra, including Capital Hill, where Australia's new Parliament House opened in 1988.

Protesters encouraged action on land rights and other First Nations issues including funding, political representation, self-determination and sovereignty.

Return to the original site

In 1992 on the 20th anniversary of the original protests, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was permanently re-established on its original site on the lawns outside Old Parliament House.

Protesters once again sought to raise the profile of First Nations issues, fearing those in power were again forgetting the rights of First Nations people.

Significance of the tent embassy

In 1995 the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was listed on the Register of the National Estate; the only site on the Register noted as important due to its political significance to Indigenous Australians.

Since the permanent re-establishment, protests have been held at the embassy highlighting issues including Aboriginal deaths in custody, the Howard government’s Northern Territory Intervention in 2007, and funding cuts to essential First Nations services.

The embassy remains controversial. Many people have challenged its validity and a number of arson attacks have damaged buildings within the camp.

The Aboriginal Tent Embassy is a symbol of First Nations protest against successive governments and their approach to First Nations issues. The most prominent issue being publicised by the embassy continues to be sovereignty over the Australian continent and an acknowledgement of the rights of First Nations people to self-determination.

In our collection

You may also like

References

A short history of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, The Conversation

Collaborating for Indigenous Rights

Coral Dow (Information and Research Services), Aboriginal Embassy: Icon or Eyesore?, Department of the Parliamentary Library, 2015.

Gary Foley, Andrew Schaap and Edwina Howell (eds), The Aboriginal Tent Embassy: Sovereignty, Black Power, Land Rights and the State, Routledge, London, 2013.

John Newfong, ‘The Aboriginal Embassy: Its purpose and aims’ in Identity, July 1972.