Ancient Greeks: Athletes, Warriors and Heroes explored competition through sport, politics, drama, music and warfare, illuminated by more than 170 objects from the British Museum.

The exhibition featured Exekias’s amphora showing the Greek warrior Achilles slaying the Amazon Queen Penthesileia and the marble relief known as the Apotheosis of Homer, by Archelaos of Priene.

Ancient Greeks: Athletes, Warriors and Heroes was on show at the National Museum of Australia from 17 December 2021 until 1 May 2022.

Explore collection highlights

Learn about the Zantiotis family of Gunnedah and an important chapter of our cultural and culinary history.

Read about one of only three known traditional formal costumes from Castellorizo, Greece.

Explore works showcasing the lifelong passion and skill of a Greek-Australian needleworker.

The presentation of Ancient Greeks: Athletes, Warriors and Heroes is a collaboration between the British Museum, Western Australian Museum, National Museum of Australia and Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum.

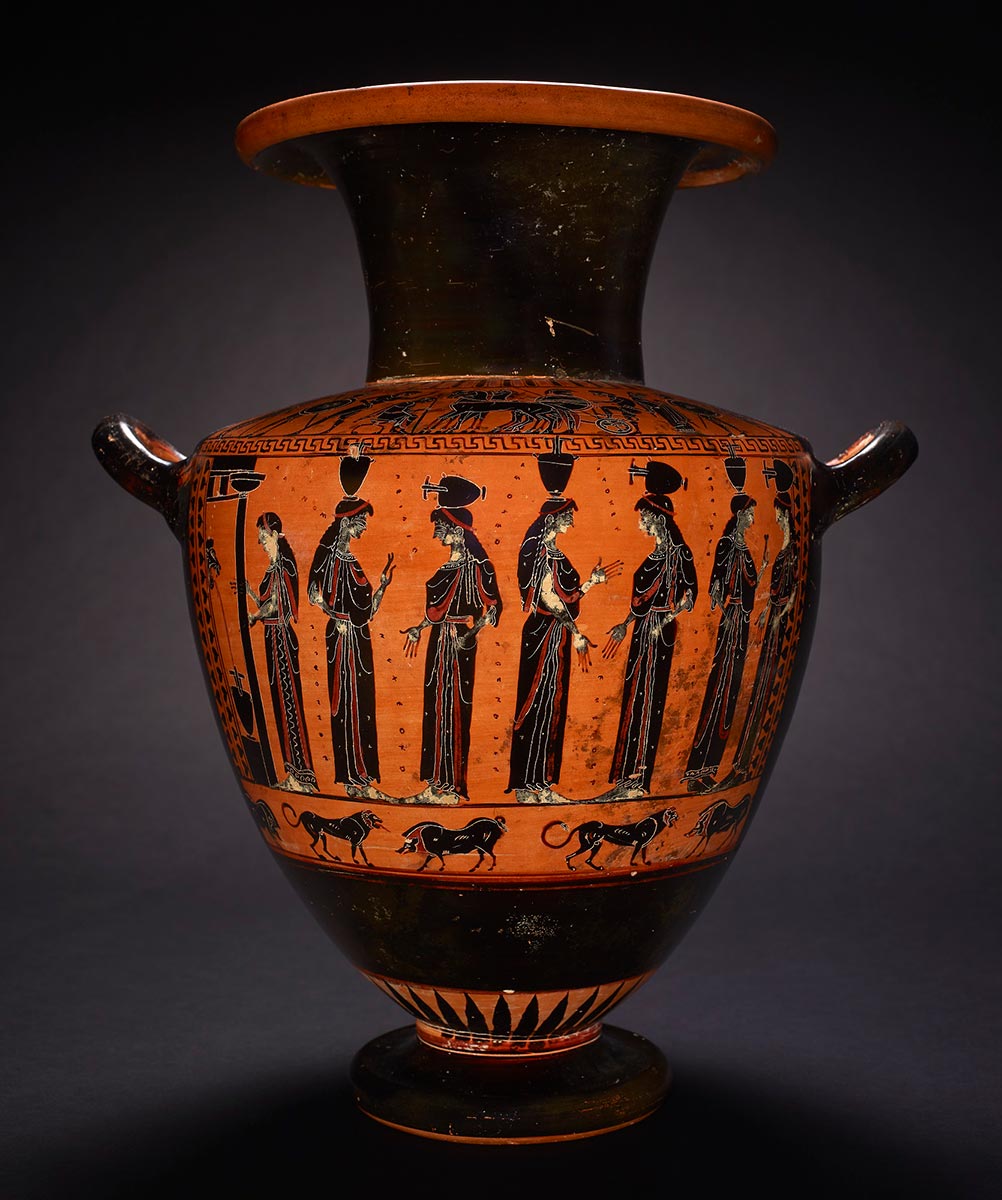

Thumbnail image: Hydria (water jar), black figure pottery, made in Athens, Greece, about 510 BCE, attributed to the Antimenes Painter, found at Vulci, Lazio, Italy, 47 x 39 x 33 cm, 1843,1103.66. © The Trustees of the British Museum, 2021. All rights reserved