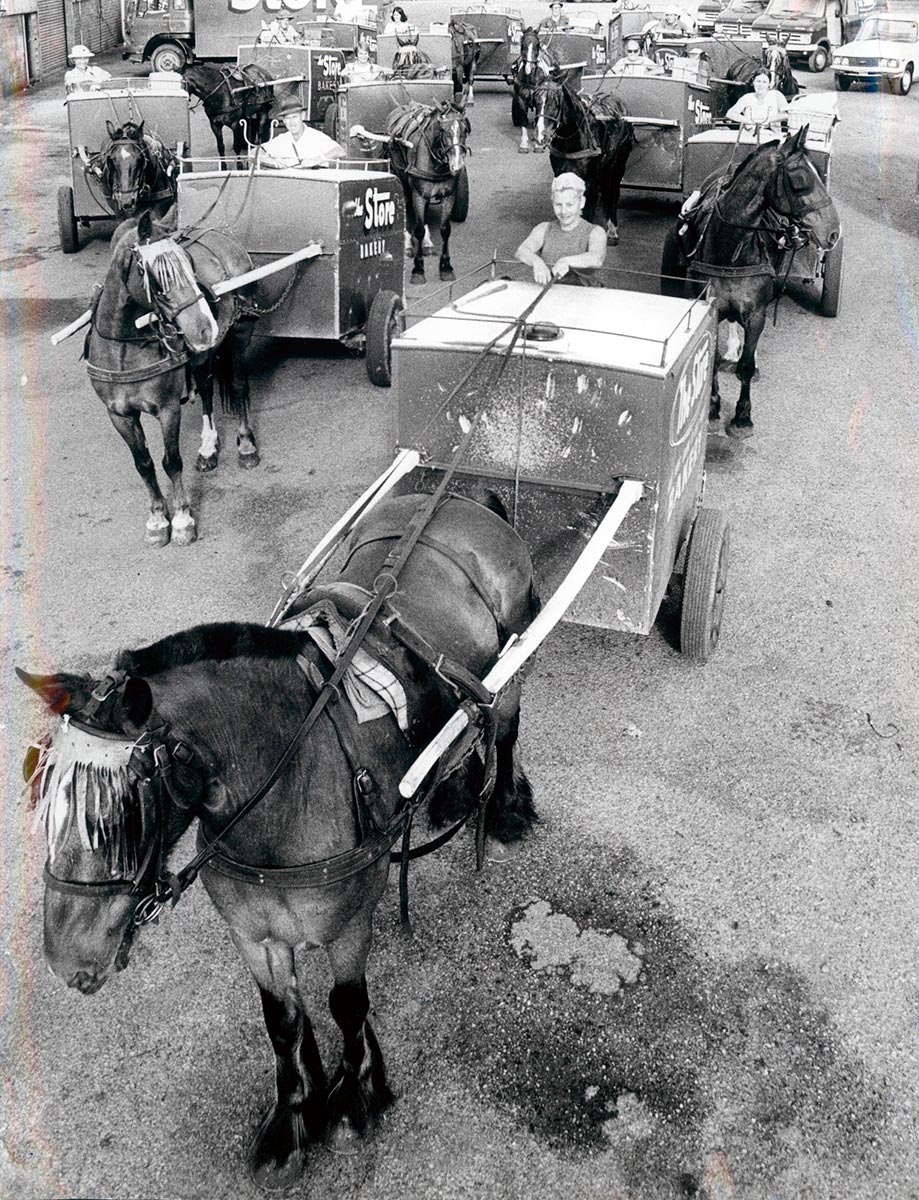

Bakery cart no. 168 was part of the fleet of delivery vehicles operated by the Newcastle & Suburban Co-operative Society.

In the 1970s the co-op's bakery was considered the largest in the Southern Hemisphere and carts like this were used to deliver more than 100,000 loaves a week across the Hunter Valley region of New South Wales.

Newcastle & Suburban Co-operative

The Newcastle Co-operative was established in 1898.

Historian Patricia Hampton notes that its beginnings were 'precarious' operating from a rented shop in Wickham with a stock valued at 25 pounds and reliant on an aged horse rescued from the Hexham swamps and a delivery vehicle put together from donated items.

By 1900 the co-op had a membership of just 95. In contrast, at its peak in the 1970s it was the largest retail co-operative in the Southern Hemisphere, and was known as 'The Store'.

The range of the co-op was vast. Apart from home-delivered produce and groceries, it sold clothing and furniture and ran lottery offices, a barber shop, insurance company, credit union and social and sporting clubs.

The Newcastle Herald reported that membership approached 100,000, which was estimated to represent approximately one in every four families in the Hunter.

By 1981 the co-op was closed. Hampton observed that newer members were not committed to the co-operative principles, were more selective in their purchases and had more freedom of choice with the rise of the family car. The co-op also failed to meet the challenge of new retail giants Woolworths and GJ Coles.

Cart no. 168

It is likely that this was one of the carts relied upon in the boom experienced at the Newcastle co-op after the Second World War. While its appearance has more in common with those typically built at the turn of the 19th century, the construction of the cart is likely to have taken place about 1940.

The cart has panels of Masonite in the roof and the lower part of the body. Masonite was mass-produced in the United States from 1929. In Australia, production of 'true hardboard' began at Raymond Terrace (a short distance from Newcastle) in 1938.

Cart conservation

This cart was housed in the warehouse of a Newcastle office supply company, along with its companion cart, no. 167, when curator Nicole McLennan saw it advertised for sale at an online auction site in 2013. The carts had been used as part of the firm’s roadside Christmas display in previous years.

After assessing the condition of both carts, the Museum decided to purchase cart no. 168, which was still in need of significant conservation treatment. The paint on the cart’s body was dry and powdery while that on the upper section, painted onto canvas panels, was deeply cracked but stable.

The worst damage was to the paint on the wheels which, like the surface of the undercarriage, was cracked and peeling away from the wood and metal of the cart. One of the leather guards on the wheel shaft was loose and distorted.

Conservators Lilly Vermeesch and Kerryn Wagg, led by Kathryn Ferguson, undertook intensive conservation work which involved softening the dry paint using damp blotters and steam and then reattaching the paint to the cart using heat activated conservation grade adhesives. The slumped canvas panels were relaxed with damp blotters and then reattached to their frames.

The team consolidated the paint on the canvas panels with a fine spray of the same conservation grade adhesive. The leather guard was gently humidified and re-conformed so its shape matched the shaft on the other side.

Bakery department

The bakery department became an essential commercial arm of the Newcastle Co-operative. The first bakehouse was built in 1908 and produced about 4000 loaves of bread each week. Prior to its establishment, the co-op employed external carters to deliver bread to society members on a commission basis.

The department continued to expand with an enlargement of the bakehouse in 1911 to incorporate a further two ovens, a loading dock and flour store. According to the co-op's official history, bread sales roughly trebled from £5,982 in 1911 to £17,037 in 1915. This equated to sales of more than 15,000 loaves a week in 1915.

Bakery key to positive image

It was recognised that the bakery department was vital to the promotion of a positive image of the co-op; it was where the customer and the store were in daily contact, usually through the bread carter. As the Newcastle co-op history stated: '[t]he Society's bread must be good'.

Further additions were made to the bakehouse and a new manager was employed with 'favourable credentials' from the Lithgow co-operative society.

In December 1923, however, even the president complained about the quality of Saturday bread. Despite the quality, the number of loaves sold continued to rise and by 1925 had risen to 24,500 a week.

In 1937 expansion of sales and the need to modernise led to the relocation of the bakery to a new premises in Clyde Street. By 1942 it was believed that the bakery had become 'perhaps the largest in Australia', baking some 62,800 loaves a week from 600 ton of flour.

During the Second World War Two, with the restrictions of zoning on bread deliveries, the performance of the Newcastle co-op's bread carters came under scrutiny. The co-op appealed to the government to review its zoning claiming it had been 'short zoned'.

Government investigations, however, focused on complaints about the service of the co-op staff and the carters in particular. Investigators claimed that the co-op's loss of trade was not the result of zoning, but 'due to gross neglect on the part of the Society's carters involving missing whole streets of householders, impudence to inoffensive people and non-consideration of shop requirements'.

The co-op's own questionnaire revealed a much smaller level of dissatisfaction but it appears that bread carters did not always present the best face of the co-op.

With the end of zoning in April 1946, bread carters (impudent or not) were in demand. In the five weeks following, it was said that the number of runs doubled, production increased from 67,000 to 90,000 loaves a week and consequently, the co-op battled to secure sufficient horses and harness.

The bakery department's rapid expansion continued. By June almost 100,000 loaves were being baked a week.

Horses at the co-op

Haulage horses were central to the operation of the Newcastle co-op in the first half of the 20th century.

Horses were needed to move stock from the railway to the store (and later its branches) and were crucial to the delivery of bread, milk and other products.

Much of the work in relation to the care of horses and the manufacture and maintenance of harness and vehicles was undertaken in-house. In 1913 new stables were built for the horses used by the co-op.

A blacksmith's shop was built in 1925 and two years later a building was erected to accommodate the garage and coachbuilding sections. The blacksmith's department alone comprised carpenters, vehicle body builders, wheelwrights, general smiths, farriers, garage workers and painters.

Attention was also paid to ensuring that the co-op's horses were able to perform the work required. A register of property and assets shows that the first eight months of 1936, for example, saw a large turnover in the co-op's horses with the purchase of Darkie, Sailor, Peter, Soldier, Red, Ralph, Wally and Chum for an average price of £20; and the sale of Satan, Sal, Billy, Noble, Tony and Trump for an average price of just under £8.

Bread carters

The number of carters (like horses) is likely to have fluctuated with the demand for bread, especially in the depression years and wartime zone restrictions. The co-op's register of staff provides a snapshot of the men who worked in the bakery delivery department in 1933, 1940 and 1945.

The number employed in the department more than doubled from 46 in 1940 to 102 following the end of zoning in 1945. In each period, there was a core of men who had remained employed by the co-op for 10 or more years.

Perhaps the longest serving was Mr C Watson who had commenced service in 1906 and was still employed 34 years later.

A 'history questionnaire' conducted by the co-op in 1933 allows a deeper look at the co-op's bread carters. Some, like Ivor Bendor, joined as a bread carter but had 'a view to further advancement' hoping to be placed in the ironmongery or men's clothing department.

Bread carter, Robert Clarke, who was perhaps disadvantaged by the Depression years, hoped to move into the clerical department, as he was 'a qualified book-keeper'.

Most, like George Nipper (who had been in service at the co-op for 10 years), began working for the co-op as a bread carter, remained a bread carter and did not indicate that they desired to change the direction of their employment.

In the 1960s the co-op still had 85 horsedrawn vehicles in service. Local resident, Ian Jordan recalled waiting on the verandah during the school holidays for the arrival of the horse drawn Newcastle & Suburban Co-op bakers cart so he could:

hand over the token and race into the kitchen with the bread still warm to get a sandwich made for morning tea. On other days, you would leave a token on a chair with a tea towel and the bread would be left under the tea towel to keep the flies off – no plastic packaging!

In about 1965 Jean Abrahams was one of the female bread carters that was employed by the co-op. Jean teamed up with Matt, an eight-year-old Clydesdale.

Matt knew the route well and while Jean was delivering bread at one house would move on to the next customer and wait. Although on more than one occasion Matt caused 'high drama' at the end of the run when he would 'take off back to the bakehouse at full speed', keen for a hose down and roll in the sandpit.

Horses in the city

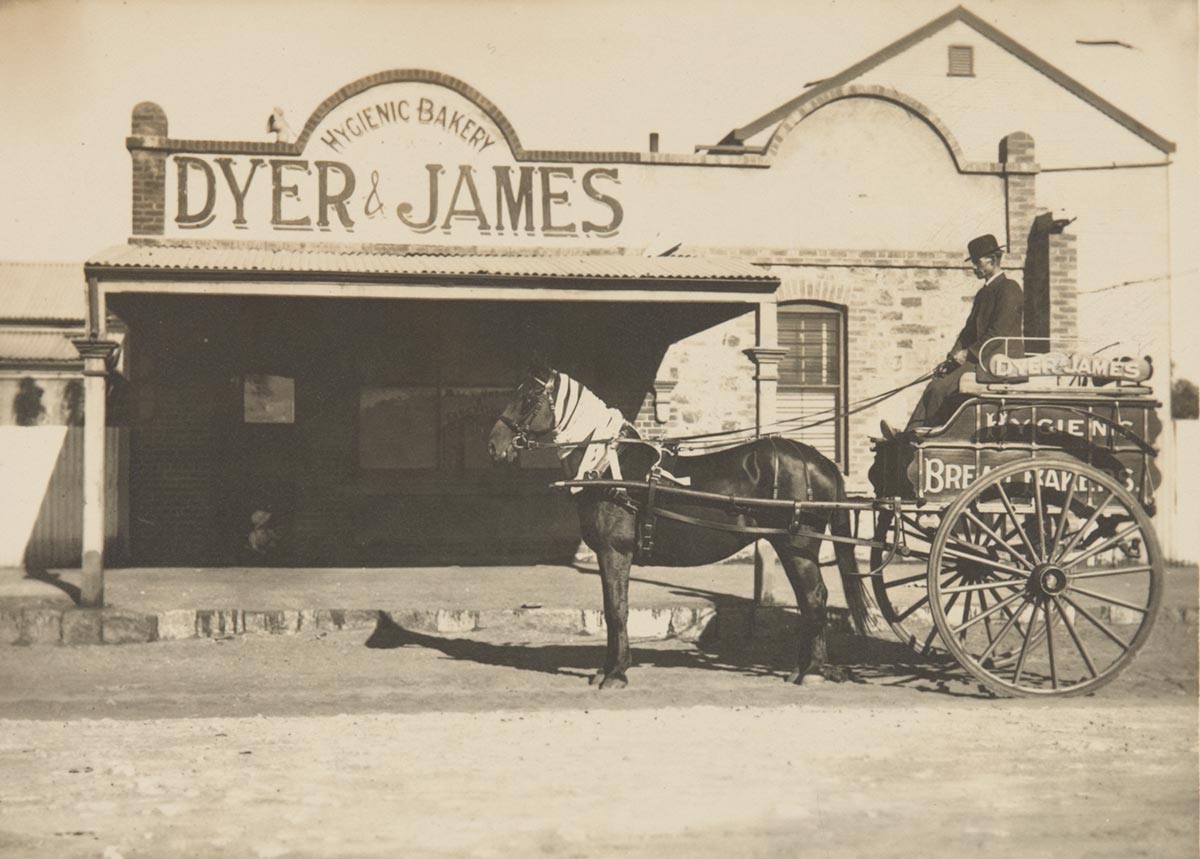

The Newcastle and Suburban Co-op bakery cart is a reminder that well into the early 20th century, urban areas were home to both humans and horses.

Historian Margo Beasley has noted that the use of the horse in urban areas was in tune with the 'localised structure of retailing and … manufacturing technology of the times'. Suburbs would have nearby dairies and bakeries, deliveries in horsedrawn vehicles were made of milk, bread, ice, fruit and vegetables. Locals would hear the call or the bottle-oh and rabbitoh men.

Even after the arrival of the car, the flexibility of the horse remained an argument for its continuing use. In a 1924 issue of the Agricultural Gazette of New South Wales, JF McEachran evaluated the relative costs of the horse with motor transport in Sydney.

He argued that in businesses like carrying, while mechanical transport was 'sometimes beneficial' over long distances, it was 'economically bad' over short distances in the cities. In these circumstances, horse power remained well-suited for short local trips within small districts and the delivery of perishable staples such as ice, bread, milk and ice, and the collection of rubbish.

Moreover, the troubled economic circumstances of the 1930s and fuel shortages of the 1940s tended to keep horsedrawn vehicles on the road when motor vehicles might otherwise have taken their place.

In the second half of the 20th century, however, most horses had disappeared from the streets. Historian Andrew May notes that in 1953 Melbourne's horse population was estimated at barely 500, mainly employed pulling milk and bakers carts or council drays, or the odd butcher's and stationer's delivery wagon.

Alongside the local milk round, it was bakery carts, like cart no. 168, which was the 'last haven' of the horse in the city where the horses knew the route as intimately as their drivers.

Decline of the co-operative movement

Cart no. 168 with its nostalgic design is perhaps emblematic of the Newcastle & Suburban Co-operative and the co-operative system generally.

While the Newcastle co-op enjoyed remarkable success for much of its 83 years of operation, in many respects the co-operative system had its heyday in the horsedrawn era from the 1850s through to the early 20th century.

Historians Greg Patmore and Nikola Balnave note that, based on the Rochdale movement, Australia's co-operatives developed 'in waves' from the mid-19th century through to the end of the Second World War and then declined in the decade after.

The co-operative movement had its origins in the ideas of Welsh social reformer, Robert Owen, who thought that 'communities based on co-operation rather than competition would eliminate unemployment and pauperism and create prosperous and harmonious community'.

The Rochdale co-operative movement overlaid these ideas with a set of principles, which included cash only purchases and a dividend (divvy) that was redistributed to members.

Patricia Hampton notes that it was British mining communities that made up many of the earliest supporters of the Rochdale system and it was from miners who had their origin in these communities that 'the co-operative tradition' arrived in the Hunter Valley.

Co-operatives were not confined to mining and examples in Australia could be (and in some cases can still be) found in the dairy, poultry and fruit growing industries and in towns with major railway junctions. Yet it was the Hunter Valley, as well as other mining districts, that became a 'very early retail co-operative stronghold'.

The Newcastle co-op was just one among many co-operatives operating in the Hunter region. The first co-operative society was the Burwood Society that was formed in 1886 by three former miners from Durham and one other man. Like many of the early societies it was short-lived, surviving only until 1892.

Reliant on the support of the local mining community for membership, it was also subject to the fluctuations of boom and bust in the industry. Patricia Hampton notes that in the following decades almost 20 more co-operatives formed in the Hunter Valley. Most lasted a few years and only the most successful, survived into the second half of the 20th century.

There were very few co-operatives that, like the Newcastle & Suburban co-op, were able to secure a more broadly working class membership base and could maintain the principle of cash only sales (rather than credit) ensuring the firm's enduring liquidity.

Even the mighty 'Store' could not survive in the late 20th century when urban centres like Newcastle lost its community-oriented focus.

In our collection