Mike Pickering:

The museum is a foreign country: we do things differently here.

An introduction to Yiwarra Kuju by Michael Pickering, National Museum of Australia

Can there be anyone nowadays who is unaware of Australian Indigenous art? It adorns walls, books, aircraft, passports, tea towels and clothing. The familiar dots, lines, plants and animals have become an integral part of modern Australia's cultural iconography.

And who is not familiar with the 'sincerity shot': a politician or a businessman or woman is photographed standing in front of an Indigenous artwork?

The display of large Indigenous paintings in corporate foyers implicitly bestows integrity on the corporation or the CEO; it says, 'We have Aboriginal art ... We care about people and culture ... Trust us'.

But rarely if ever is the work itself explained, or even titled. And nowhere is the artist acknowledged. Everyone is aware of Indigenous art – but there is so much more to know.

Few suspect the complex and rich stories behind many of these works. How many appreciate the works not just for their aesthetic appeal, but also for their sacred and secular stories, and for the histories and experiences they embody?

We see so much, and yet we see so little. An encounter with the Canning Stock Route collection will allow us, in part at least, to address this cultural lacuna.

The Canning Stock Route runs 1850 kilometres through northern Western Australia. Stock routes were developed across Australia as the pastoral industry expanded. A stock route was essentially a defined route through Crown Land along which cattle could be driven either between pastoral properties or from pasture to market.

Such routes typically allowed for access to waters and grasslands so that stock could be fed and watered. It is not unusual, therefore, to find that they often take in stream corridors, lakes, ponds and waterholes.

These corridors of Crown Land, officially 2 to 3 kilometres wide, allowed for the free movement of stock through the freehold and leasehold lands of the pastoral stations. Many Aboriginal people found work as stockmen and support labour in the pastoral industry.

The history of the Canning Stock Route is, therefore, not just an important story of the development of the north of the state of Western Australia; it is also a case study of the events and issues that accompanied the development of stock routes across Australia. As such, it is a national story.

In 2008 the National Museum of Australia acquired the extensive collection of works now known as the Canning Stock Route collection – a relatively humble name for a collection of such national significance. The acquisition of the entire collection was unusual in that it was an evolutionary process.

Initially, an independent Western Australian arts organisation, FORM, approached the Museum with the request to stage an exhibition of works that would be created during their Canning Stock Route Project. A straightforward, and not unusual, request.

The Museum receives many such offers each year. Very few are accepted, usually because, although often impressive in various ways, they do not satisfy the Museum's need for exhibitions that reflect deeper social histories.

In this case, however, the exhibition proposal was tantalising.

It was clear that there were major stories behind the works: stories of people and places, of the clash of cultures, survival and resilience, and histories, both sacred and secular.

The Museum decided first to host the Yiwarra Kuju exhibition, then to be a partner in its development.

When confronted by the wealth of information implicit in the works and explicit in the accompanying documentation, the Museum decided that this was a collection of national importance.

And so the Museum acquired a collection of artworks. What's so special? Surely art galleries do such things all the time. But to adapt LP Hartley's famous line, 'The museum is a foreign country: we do things differently here'.

What do museum curators look for when they acquire an object? In truth the most desirable works are those that emerge from experiences and lives shaped by history and culture.

We look for attributes in objects, whether works of art or pieces of machinery, which help to tell the stories of those histories and cultures. We seek narratives. The object has to act as a 'go-between' — to borrow once more from Hartley – for stories and their audiences, becoming itself an icon that encapsulates and communicates meaning.

Our goal is for audiences to enjoy the object in its own right, but then look deeper, past the object itself and into the sacred and secular stories it can be used to communicate.

We want audiences to be informed about the creators of the works and about the events, stories and beliefs that have shaped their lives. Objects are just like history books, biographies, TV documentaries or sacred texts: they can entertain and inform us, about others and about ourselves.

The objects that make up the Canning Stock Route collection do all of this. This is a fantastic collection, characterised by diversity, both in objects and narratives. It has been amassed with the full participation and collaboration of the artists and storytellers, which makes it, first and foremost, a collection of 'first voices', mediated by the non-Indigenous members of the project team.

By listening to their stories, we can all come to have a better appreciation of how these artists and storytellers see their world.

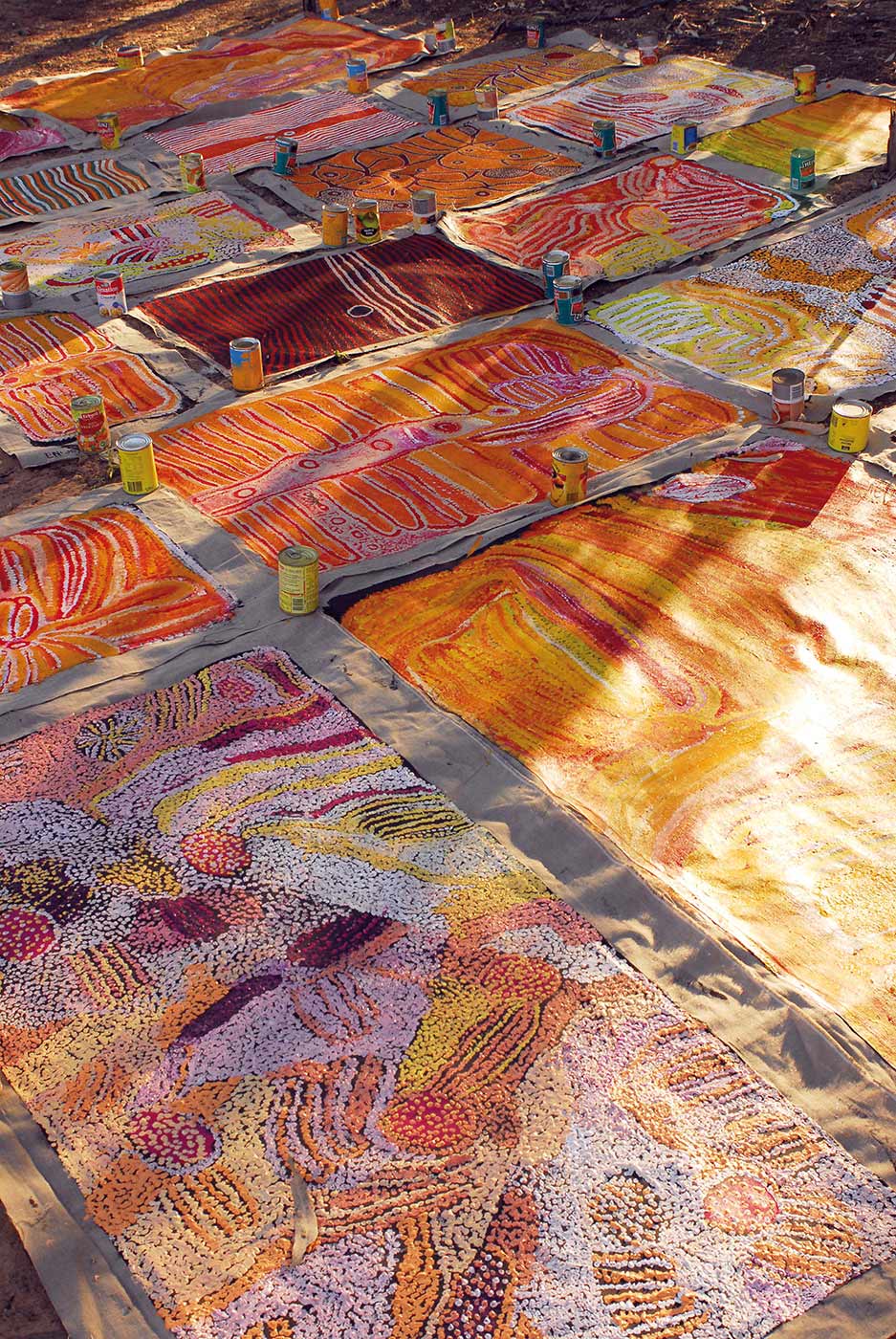

There is a real joy to be had in looking at the works of art. Some are highly polished, the products of experienced artists; others are a little more 'rough' in their technique, the products of first-time artists, across all age groups, or of elders with failing eyesight. But it is in this diversity of technique that the real appeal lies.

Sometimes there is an occasional drip of paint in the wrong spot, or a place where the artist has gone over the edge of the canvas. Such things are not flaws, but rather reminders that the artists are not painting to satisfy criteria such as price or Western techniques and conventions, but simply to express the joy they experience in telling their stories.

Aboriginal people love to share knowledge with people who are interested in receiving it. And so the works they have created represent a triumph of passion over convention.

But while the works themselves are wonderful, they are only part of the collection. Their full potential is only realised when we add in the massive social documentation that accompanies them, allowing them to be placed firmly in their historical and cultural contexts. Without this information, any work of art is little more than decorative.

The collection tells stories of Aboriginal history, of personal experiences and of events and beliefs that shaped the lives of individuals and their societies. It reminds us that the artefact does not, in itself, make history – history is made, experienced and told by people.

The power of such a collection to inform our understanding of the lives and cultures of the artists and their communities is apparent. Take, for example, the stylistic diversity revealed in this collection.

In the mainstream art market, it is often assumed that different styles reflect different traditions and cultural values. Art centres such as Papunya, Warmun or Balgo are thus treated in isolation, leading to the unfortunate presumption that some styles are more significant (perhaps 'more traditional') than others.

What the Canning Stock Route collection reinforces, however, is the capacity of Aboriginal artists to develop a specific locale-based aesthetic while retaining and strengthening wider social networks.

Thus the same stories are being told through many different styles. The stories remain the same but the imagery differs.

New iconographies emerge, suggesting cultural divergence, a move away from tradition, but the stories inherent in the changed iconography – the underlying traditions, cultures and social connections – remain strong, reinforcing convergence and identity.

The Canning Stock Route collection clearly demonstrates that the different styles are a product of historical movement and cultural dynamism, not loss or erosion of tradition.

It shows us Western Desert peoples sharing common cultural values, histories and stories, and celebrating the survival and resilience of this culture and history, through the art styles of many individuals.

The collection also reflects a close collaboration between researchers and contributors. All Aboriginal participants were fully informed of the aims of the project; all were consulted about whether their stories and heritage could be held by the Museum; and all were asked to provide instructions concerning the culturally appropriate use of the collection material in the future.

At all times, they retained the power to include or restrict information, in accordance with cultural protocols. Aboriginal co-curators, filmmakers and photographers worked closely on both the project and the subsequent exhibition development, ensuring that valuable skills and experience were injected back into their communities.

For its part, the Museum has been impressed by the very high standards apparent in the research process, which offers a model for contemporary ethical museum research projects.

The story of the Canning Stock Route collection has only just begun. The works themselves are merely the tip of the iceberg. The collection's future lies in the ways it will continue to reveal hidden histories and cultural processes to a wider public, told from the perspective of the Aboriginal artists and their families.

The collection gives priority to the 'Aboriginal voice'. The artists tell us about these works in their own words. There is no need for a Western art expert to explain what the artist intended.

The collection is rich in personal histories, and in stories of sacred and secular ancestors engaged in events ancient and modern. We are privileged that the artists have so generously shared these stories with us.