An essay by Richard Reid, senior curator, National Museum of Australia

About the Irish in Australia there are always opinions, some favourable, some not.

Poet and storyteller Henry Lawson said that, when in trouble, he always had 2 friends, and one of them was an Irishman.

Visiting Adelaide in the 1870s, Richard Twopenny found to his dismay that 4 out of 5 servants were Irish – ‘liars and dirty’.

Once accused of being opposed to Irish immigration in the 1840s, leading New South Wales politician William Charles Wentworth retorted that this was a lie: ‘Some of the best blood in my veins is Irish’.

A couple of decades later the so-called ‘Father of Federation’, Henry Parkes, argued that ‘Irish Roman Catholics’ were not the ‘best people’ for the developing colony of New South Wales, and that the numbers arriving at colonial expense should be restricted.

Much later, in the 1960s, Donald Horne wrote of his Muswellbrook childhood as one in which local Catholics, the great majority of whom would have been of Irish descent, were perhaps ‘not quite human’.

So where do the Irish fit into the Australian story?

Irish-born immigrants and their descendants have been a feature of the Australian population since the arrival of the First Fleet in New South Wales in 1788.

Their influence upon, and contribution to, Australia’s ever-changing and evolving cultural, economic, political and social life was of central significance. This stems from the fact that the Irish and their descendants formed a large segment (somewhere between 20 and 30 per cent) of the population up until 1914, and some suggest well beyond that.

Before the large-scale continental European and English immigration of the post-1945 decades, Australia has been described as a ‘fairly faithful mirror of the early 19th century United Kingdom’ of Great Britain and Ireland, where the Irish formed a third of the population. Australia remains the most Irish country in the world outside Ireland.

What was the impact of this large Irish presence?

Some Irish and Irish-Australian commentators, stung perhaps by the Establishment’s relative indifference to and resentment of the Irish, especially the Irish Catholics, tended to stress the Irish contribution to society in a sometimes exaggerated manner. The title of PS Cleary’s book, Australia’s Debt to Irish Nation Builders, published in 1933, says it all.

John Francis Hogan also emphasised ‘Irish achievements in the land I love so well’ in his much earlier work, The Irish in Australia, written in Melbourne in the 1880s. Hogan was a true Irish colonial: born in Ireland in 1854, he arrived in the booming ‘gold’ colony with his parents as a 2 year old.

Looking towards the bicentenary of European settlement in 1988, Patrick O’Farrell produced his own view of the role of the Irish in Australia. Rejecting the celebratory approach he discerned in Hogan’s and Cleary’s books, O’Farrell produced the much more sweeping claim that it had been the Irish Catholics, by opposing the dominant Protestant English and Scottish colonial ethos, who were the galvanising force behind the development of a new Australian identity and society.

In particular, he had in mind the determination of Irish Catholics to have their world view incorporated into whatever it might mean to be ‘Australian’.

In a more cautious vein, Oliver MacDonagh claimed that a study of Australia without its Irish component ‘might not be quite Hamlet without the Prince of Denmark. But it would certainly be a shallower and a poorer play’.

The Australian story would surely be a ‘poorer play’ without the echoes of transported exiles of Erin ‘bound down by iron chains’; the orphan immigrant girls of the Great Famine of 1845–50; the Eureka rebellion’s Peter Lalor; the Kelly gang; the potato farmers of Koroit; the tragically flawed explorer Robert O’Hara Burke; the founder of Victoria’s State Library, Sir Redmond Barry; female educator Mother Mary Gonzaga Barry; Australia’s first cardinal, Patrick Francis Moran; engineer Charles Yelverton O’Connor; anti-conscription leader Archbishop Daniel Mannix; the pastoral Durack family; and a host of others.

To date, the Irish-Australian story has been told by historians, novelists, poets and balladists. They have defined its outline, mapped its general landscape and identified its key players.

Now, to bring the Australian Irish story to a present-day audience, the Museum has assembled an array of objects, documents, paintings, drawings, photographs, recorded voices, songs and moving images.

The scope and suggestiveness of this material defy easy description. Some of the objects on display clearly support broadly accepted views on the Irish; others challenge some of the narrower definitions of who or what qualifies as ‘Irish’ in an Australian context.

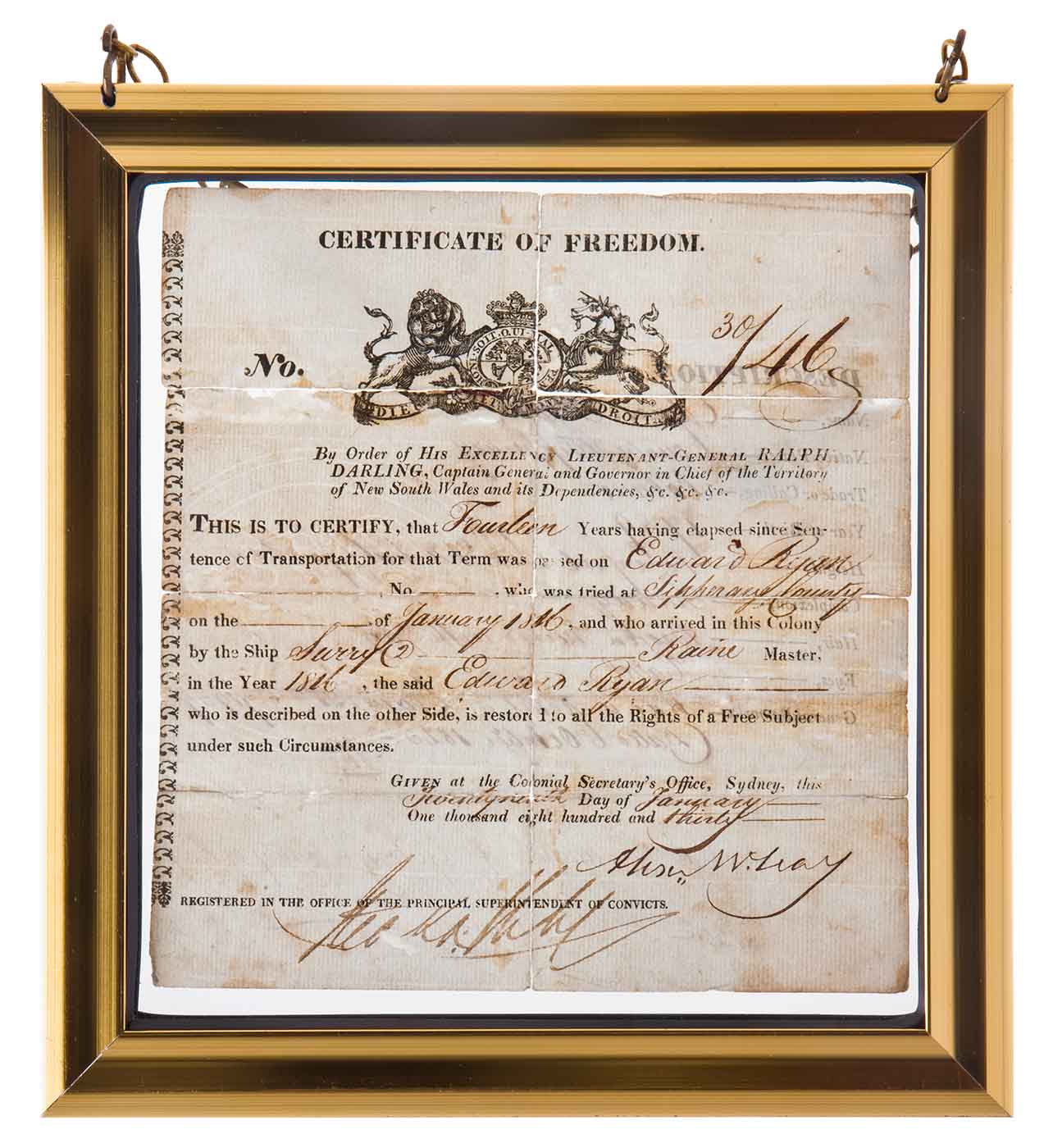

Represented are, in O’Farrell’s words, ‘all sorts and conditions of men and women’ from Ireland who, between 1788 and the present, travelled to the far side of the world as convicts or free government-assisted immigrants or passengers paying their own way.

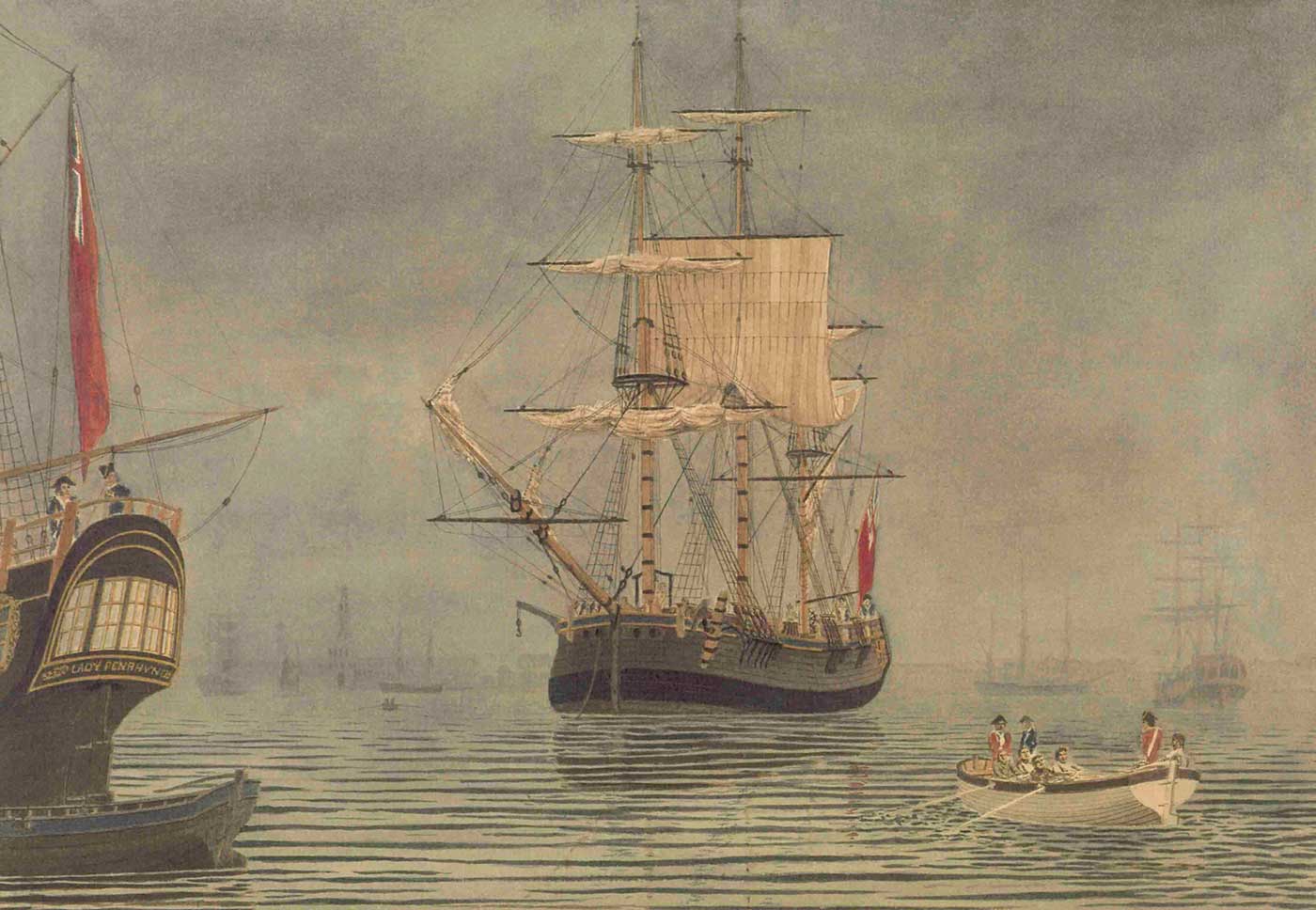

The key element in the initial Irish experience of Australia was getting here. Until the end of the 19th century, the Irish journey to Australia was largely made under governmental supervision, either in a convict transport or in a vessel chartered by a colonial government.

While there were some disastrous convict voyages, and later some equally appalling government-sponsored immigrant voyages, by and large the long sea passage was experienced under conditions markedly superior to those endured by many other emigrants during the 19th century.

Even where modern Irish memory recalls death- and disease-ridden ‘coffin ships’ heading for North America during the years of the Great Famine, colonial government emigrants were, by the standards of the day, generally well fed, adequately clothed and medically cared for.

While the most significant years of Irish emigration to Australia were over by the time of the First World War, the Irish have continued to arrive here in smaller numbers up until the present day.

Once in Australia they toiled to make a decent life for themselves and their descendants, and for the general society around them. They were involved in the creation of this new colonial society from the very beginning. Take, for example, their involvement in political life.

In the mid-1850s, on the goldfields of Victoria, Irish diggers, along with the English, Scottish and men of many other nationalities, insisted on their rights to full democratic participation in colonial life, rights long denied to them by the particular social, religious and economic repressiveness of British rule in Ireland.

It was the Irish, with their symbolic password ‘Vinegar Hill’, their making of pikes and their leader Peter Lalor, who were arguably the most prominent contingent among the 150 or so diggers who bore the brunt of the police and military attack on the Eureka stockade on 3 December 1854.

The Australian achievement of male suffrage during that decade admitted Irish males into full participation in colonial affairs; as a result, Irish Catholics such as Charles Gavan Duffy, John O’Shanassy and many others were able to reach high political office, something that would have been barely conceivable in the other parliaments of the British Empire at the time.

Even a cursory examination of those Irish who have clearly contributed to Australia’s economic and cultural development produces a long list. Many of the thousands of Irish immigrants were highly qualified, as evidenced by their success in manufacturing, agriculture, pastoralism, the law, science, medicine, prospecting, engineering and many other walks of life.

A surviving Union combine harvester, built in 1898, is a reminder that it was Irishman James Morrow who produced Australia’s first viable combine harvester. The Lennon Foundry, founded by Irishman Hugh Lennon, was the largest of its kind in Victoria, and it was the mould boards from Lennon ploughs that the Kelly gang beat into Australia’s most famous suits of armour. A significant number of colonial governors and senior members of the judiciary were Irish, among them Sir Richard Bourke, the Earl of Belmore, Sir John Madden and Sir Redmond Barry.

The contribution of the Irish-born and their descendants to Australian culture generally – to literature, music, sport, the theatre, filmmaking and art – was considerable and continues to this day. The Irish, as one ballad has it, ‘gave us our songs to sing’, and the Australian folk music scene provides plenty of evidence of what that genre owes to Ireland.

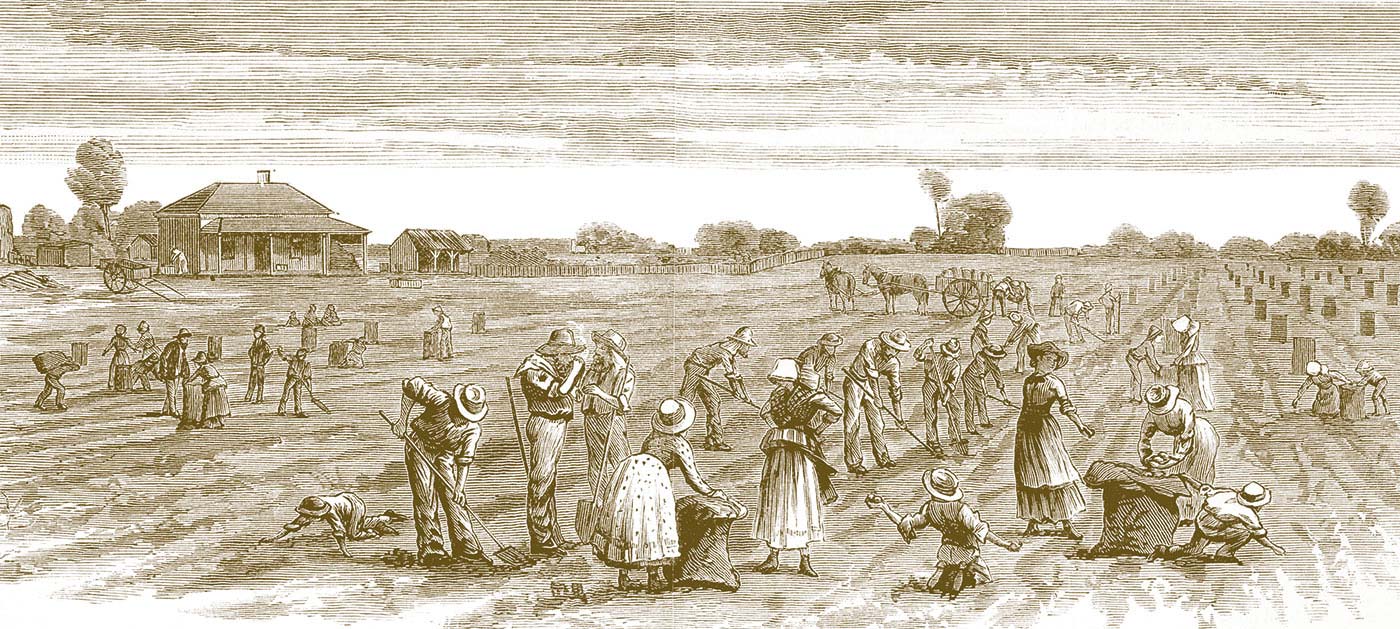

Most 19th-century Irish immigrants, however, especially the Catholics, gained employment initially in domestic service and in the dozens of lowly labouring occupations that made up the urban and rural workforce. They came from fairly impoverished rural regions and possessed few skills beyond some basic literacy. It was their children and grandchildren who rose up through the ranks of Australian society.

Nevertheless, the Irish of all denominations spread across the continent and nowhere did they form the type of ghetto communities that were such a feature in American and British cities.

Some locations, such as Koroit in Victoria, Kapunda in South Australia and Kiama in New South Wales had disproportionate numbers of Irish settlers, but virtually every community in every colony had its Irish component.

The descendants of the Catholic Irish often feel that their ancestors were victims in Australia of continuing British Protestant bigotry and discrimination. Phrases like ‘No Irish need apply’ or ‘No Catholic need apply’ spring to mind here.

Informal employment practices that did exclude Irish Catholics from certain workplaces certainly existed well into the 20th century. Yet, the full story here is still unclear.

Recent research shows that at the census of 1901 Australian Catholics, the overwhelming majority of them Irish or of Irish descent, were fairly evenly spread through all occupational groups, with the exception of high finance.

Oliver MacDonagh, quoting 1933 census figures, has shown that by that time Australian Catholics were proportionally spread through all income levels in Australia. If the Irish and their descendants, he argues, lagged economically behind the English and the Scottish, it was ‘only by one or two steps’.

If the Catholic Irish felt themselves discriminated against, there was a segment of Australia’s population that was far worse off than they were – the Indigenous people.

The engagement of the Irish with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is a largely unwritten story. Some are inclined to see it as one where already downtrodden Irish Catholics must have enjoyed a fellow feeling with a similarly oppressed people. There is little evidence to support this, however. The frontier violence that marked European–Aboriginal relations, in all regions of initial contact since 1788, had its Irish participants.

But there are individual instances of more positive encounters, such as the work of Irish-Australian anthropologist Frank Gillen in central Australia between 1875 and 1903. One journalist recently wondered why the exploits of sporting heroes and racehorses are more celebrated than that of such ‘ethical and visionary white men’ as Gillen.

There is also the complex story of the Irish Sisters of St John of God in north-west Australia. While the sisters were implicated in the system that removed Aboriginal children from their families (the ‘Stolen Generation’), they also believed (rightly or wrongly) in the transformative power of education.

These histories are not easy, but in an age of reconciliation they must be considered within the frame of the Irish-Australian story.

While the majority of Irish immigrants, like many others, quietly worked away on the land and in towns and cities to improve their condition and that of their families, some became caught up in defining moments of the national story. As O’Farrell states, ‘Where the action was in Australian history, there also were the Irish’.

At times the 80 per cent or so of the Irish who were Catholic stood apart from the British-orientated majority, and opposed those who insisted that the only decent and loyal Australian was a good overseas ‘Briton’. In that struggle, many commentators now see the Irish Catholics as solidly in the vanguard with those who sought a distinctively ‘Australian’ definition of themselves.

From as early as the 1840s right through to 1921, support for the various national causes of ‘old Ireland’ sometimes provided such men and women with a sense of being a Catholic Australian of Irish origin – a sense that was sharpened in the late 1860s and 1870s by events that led many of their British colonial compatriots to view Irish Catholics as potentially violent, rebellious and hostile to the British Empire.

In 1868 an Irishman, described in the Australian Dictionary of Biography as a ‘paranoic’ and claiming to be a member of the ‘Fenians’ (a secret brotherhood dedicated to the violent overthrow of British rule in Ireland) attempted to assassinate Australia’s first British royal visitor, Prince Alfred, the Duke of Edinburgh.

Adding insult to injury, in 1876 the American Fenians organised Australia’s first and last transoceanic prison break by snatching 6 Irish Fenian rebels from Fremantle Prison and sailing them to freedom in the United States on the American whaler Catalpa.

And in the late 1870s, the outlaws of the Kelly gang rode the ranges with their unique blend of colonial Australian and poetic Irish sense of grievance. (One contemporary cartoon shows the infant Ned Kelly in his cot sucking on a bottle labelled ‘Fenianism’.)

The Kelly gang created a legend of the struggles of the ‘common man’ against the oppressions of a society whose laws and institutions grind him down. There were echoes here of ‘old Ireland’, perhaps, but it was a home-grown colonial fury sounding through the Australian bush, where small farmers and selectors faced off against haughty pastoralists and landowners backed by the police. Ironically, many of those policemen were themselves poor Irish immigrants.

With the arrival in 1884 of Irishman Patrick Francis Moran to be archbishop of Sydney, Irish Australia had a new kind of champion. Soon to be Australia’s first Catholic cardinal, Moran announced that he was ‘becoming today an Australian among Australians’.

Moran’s leadership between 1884 and 1911, while alive at times with Protestant–Catholic rancour and bitter sectarian feeling, was characterised by his insistence that Catholics take their rightful place at the centre of Australian society, a place to which their numbers entitled them. But he also urged his flock to value their Irish-Catholic inheritance.

For him, ‘Australianness’ was not simply defined by the Protestant Reformation in Britain, ‘Good Queen Bess’, Admiral Horatio Nelson and the Battle of Waterloo. It could also draw on centuries of Irish history stretching back to St Patrick, the conversion of Ireland to Christianity and the cultural achievements of the land of ‘saints and scholars’.

On 24 May 1911, shortly before his death, Moran promoted an ‘Australia Day’ in Catholic schools in opposition to the celebration of Empire Day in state schools on that same date.

During Moran’s years in Sydney, Ireland itself seemed to be moving, with significant political support in both the United Kingdom and countries of Irish settlement such as Australia, towards a form of self-government within the Empire known as ‘Home Rule’.

A growing sense among Irish Australians, and their Australian-born children, of the role that their own ancestors had played in Ireland’s struggle for independence was made visible in the creation of such monuments as the large 1798 Rebellion memorial built in Waverley Cemetery, Sydney, between 1898 and 1902, and in the unveiling in Melbourne in 1891 of the statue of Daniel O’Connell, the Irish leader who had achieved Catholic emancipation (the right of Catholics to sit in the British parliament) in 1829.

Conversely, for the Irish in Ireland, Australia was the grand model for Home Rule, the major colonies having gained that status within the Empire between the mid-1850s and the 1890s. Proportionally, more money was raised in Australia to support the Irish Nationalist Party than in the United States with its huge Irish immigrant population.

But Cardinal Moran, who emphasised Australia’s position as part of the British Empire and the significance of that relationship, is now a forgotten figure.

His mantle of leadership passed to one who did become a legend in his own long lifetime for, among other things, his support of an Irish republic – Archbishop Daniel Mannix of Melbourne.

During the terrible and divisive years of the First World War and the fierce conscription debates of 1916–17, it was Mannix who defended his co-religionists against the charge that Catholic Australia was disloyal.

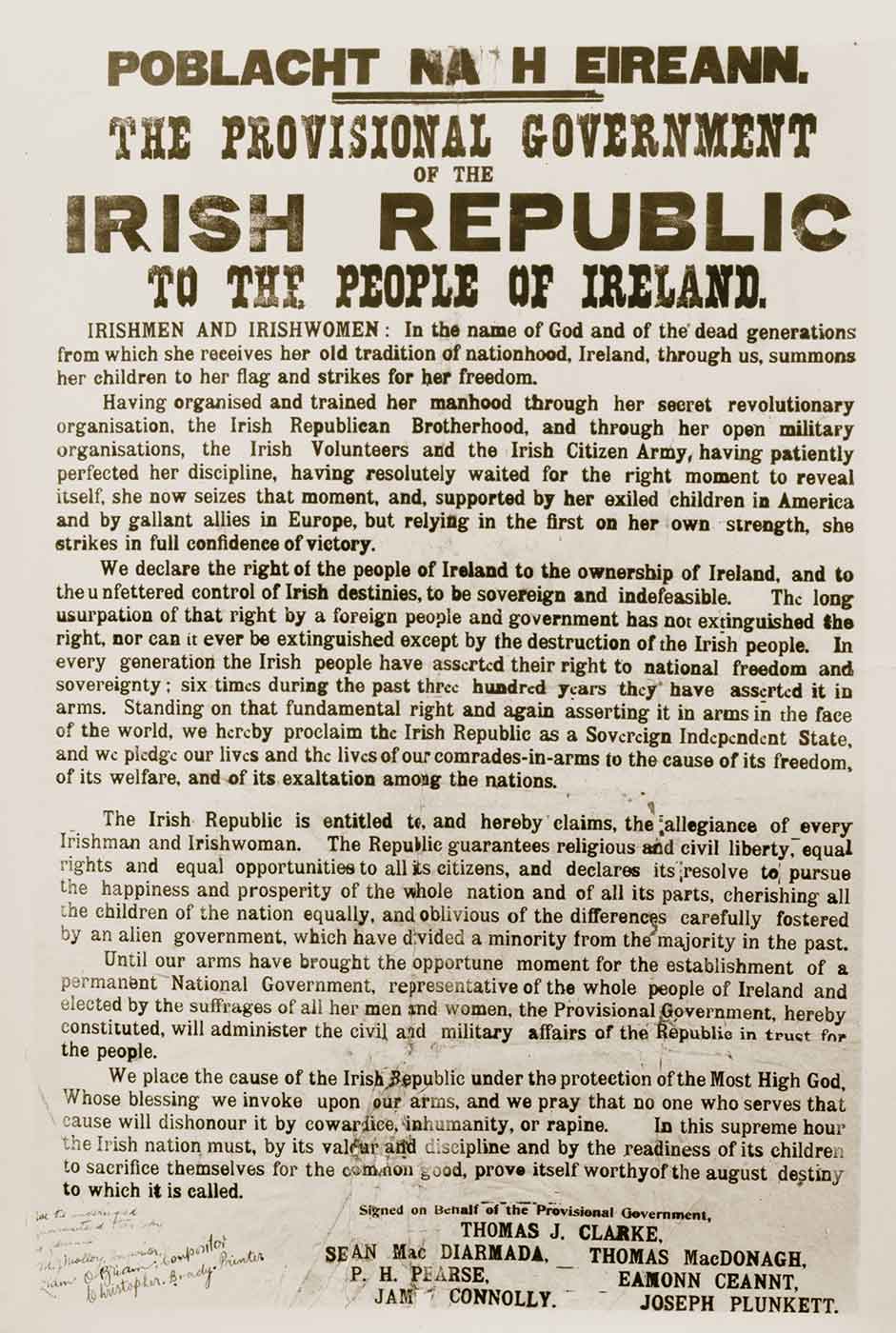

It was Mannix who presented Catholics as remaining loyal to Australia even while they looked with dismay and revulsion at the British handling of the aftermath of the Easter Rebellion in Ireland in 1916 and the subsequent Anglo–Irish War of 1919–21.

Those years are generally seen as a crisis point in Australian history, a time when anti-Catholicism and anti-Irishness was at its height, a time as bitter, rancorous and socially divisive as the now much better remembered anti-Vietnam war period of the 1960s and early 1970s.

Interestingly, former Liberal prime minister, Malcolm Fraser, recently described wartime prime minister Billy Hughes’s attributing the conscription referendum defeats to Mannix and the Irish Catholics as ‘perhaps the worst act of any prime minister in Australian history’.

Australian Catholic interest in Irish affairs, however, waned after Irish independence in 1921 and the civil war in 1922. The onset of the troubles in Northern Ireland in the late 1960s elicited some interest in Australia, but nothing like the uproar of the Mannix years. The issues at stake then were as much about the position of Australian Catholics in Australia as they were about Ireland.

Mannix remained the key figure among Catholic Australians right down to his death in 1963, and it is worth noting that he is also remembered as a champion of other immigrant groups, such as the Italians facing internment in the Second World War.

What was of greatest significance during this time was the central role Irish-Australians played in the development of the Catholic Church in Australia.

There is general agreement that up until the end of the Second World War, and well beyond, the Australian Catholic church was essentially an ‘Irish’ Catholic church. Irish clergy were prominent in Australian Catholic history from 1800 to the 1870s, but the key diocese of Sydney was in the hands of English Benedictine bishops.

The Irish lobbied hard to have an Irishman appointed there, and they succeeded with the coming of Moran in 1884.

The following decades witnessed a growing stream of priests and nuns, the majority of them Irish, arriving to build and staff developing Catholic parishes across the continent.

They were coming from an Ireland caught up, since the early 1850s, in what has been described as a ‘devotional revolution’ as the Irish church under Cardinal Moran’s uncle, Cardinal Paul Cullen, energetically pushed through a series of ecclesiastical, educational, liturgical and clerical reforms.

These same reforms worked their way through the church in Australia, producing a unified style of worship and organisation across the country that was soon simply identified as ‘Irish-Catholic’, although in style and appearance it owed much to European Catholic forms.

Both Moran and Cullen had spent their formative years in Rome. This ‘revolution’ has been interpreted as an international Irish-Catholic resurgence after nearly 150 years of Gaelic Irish cultural decline, which the Catholic Church took little interest in arresting, and the gradual Anglicisation of Ireland.

Many Protestants and Empire loyalists had always looked with alarm at the growing assertiveness of Catholic Australia under men like Moran, Mannix and the other Irish-born prelates.

After the attempted assassination of Prince Alfred in 1868, the Orange Order, which had come to Australia with the large number of Ulster Protestant government-assisted immigrants, grew quickly.

The organisation’s deep hostility to Catholicism and its admonitions to defend those bulwarks of British constitutional freedom – the King James Bible and the monarchy – appealed to many English and Scottish settlers who were alarmed by a supposedly growing Irish and Catholic threat to these institutions.

While never a huge organisation, the Orange movement spread around colonial Australia, and members acted as the voice of concerned Imperial Protestantism in the face of movements like Home Rule and other perceived Catholic threats.

At its most basic level, larrikin ‘Orange’ and ‘Green’ gangs brawled in Sydney’s Rocks area in the 1870s. When high-profile Catholic candidates, such as Cardinal Moran, failed to gain political office, in the election for delegates to the 1898 Federal Convention, they were inclined to blame this on the Orange factor.

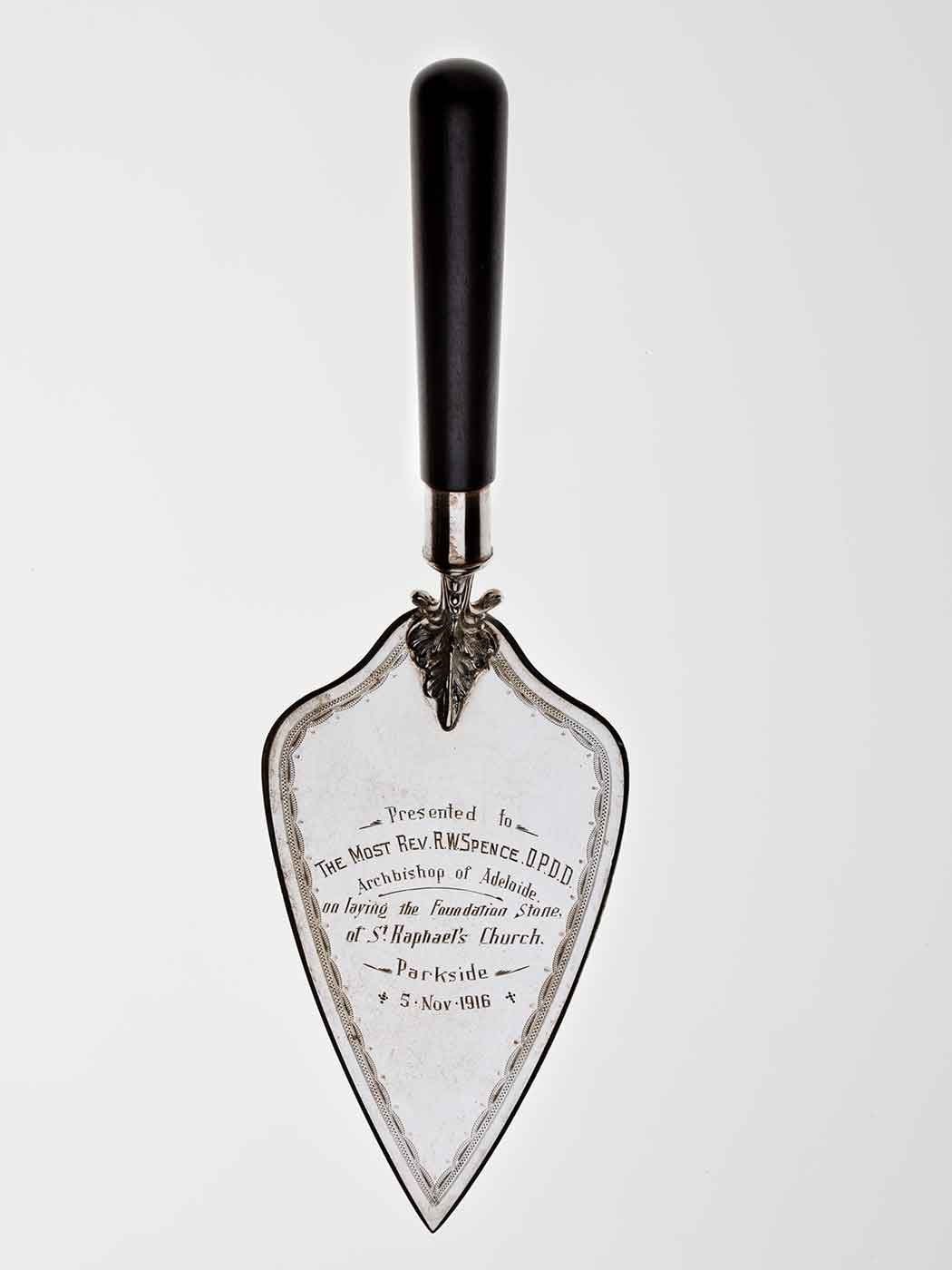

The Moran years, and beyond, were also marked by a great flood of building – churches, convents, schools and presbyteries – mostly achieved through the strength of financial donations from the congregations who crowded to mass Sunday after Sunday.

Prominent builders were Irishmen such as Archbishop William Spence of Adelaide during the period 1915–34 and Archbishop James Duhig who ruled the Archdiocese of Brisbane between 1917 and 1965. Like nothing else, these buildings pointed to Irish-Catholic success in the colonies.

When they attended mass, parishioners heard bishops and priests, many of them with Irish accents and acknowledged leaders of the community, speak out on both religious and non-religious matters of the day. Priests were central figures in their parishes, while Irish nuns and brothers staffed and ran school systems that are still part of the fabric of Catholic Australia.

Beginning in the 1860s, the development of a separate Catholic education system, founded on the financial contributions of the faithful and the hard unpaid work of the male and female religious orders, created a distinct intellectual and emotional ambience for Australian Catholic youth.

The system was developed in opposition to the colonial ‘free, secular, and compulsory’ state education systems introduced between the 1860s and the 1880s, and it drove a wedge between Irish-Catholic Australia and British Australia. The bishops saw the state schools as godless institutions; they wanted Catholic children to be educated in purely Catholic surroundings.

There might not have been trouble over all this but for the fact that colonial and, later, state governments refused public money to Catholic schools. This meant that ordinary Catholics had to support their own schools and also help to support the public system through their taxes — a situation that produced a deep and abiding sense of grievance among 20 to 25 per cent of Australia’s population.

Up until 1945 the Catholic parish, with its primary school, convent, church and presbytery, had a decidedly Irish-Catholic atmosphere and later became the hub of Australian Catholic life.

Blessed with a host of distinctive characters, Catholic society found its greatest singer in ‘John O’Brien’ (Father Patrick Hartigan), born of Irish parents in Yass, New South Wales, in 1878. His book of verse, Around the Boree Log, published in 1921, celebrates the Catholic and Irish life of bush parishes, but it touched a nerve among Catholics nationwide and became a bestseller.

As Australian society recovered from war, the social and political acrimony of the conscription issue and postwar divisions over Irish independence in the 1920s and 1930s, many Australian Catholics centred their non-working lives on the parish and its various social and religious institutions.

The laity achieved a sense of close personal identity with the church through membership of organisations such as the Australian Holy Catholic Guild, the Hibernian-Australasian Catholic Benefit Society, the Children of Mary and other sodalities and confraternities.

The strength of this Australian Catholic lifestyle was on full view on such great occasions as Sydney’s Eucharistic Congress of 1928. The event symbolised the extraordinary spiritual and institutional power and reach of a Catholic church still very much in the hands of Irish priests and prelates.

Even today, it is hard to imagine Sydney streets packed with about 750,000 people waiting to see the sacred Host, at the centre of an 18,000-strong procession, carried up from Circular Quay to St Mary’s Cathedral for a Congress mass. Such displays, and there were others over the years, marked the public high point of an Irish-Catholic Australia.

Leaders such as Mannix, and Moran before him, probably both alienated and angered anyone of Irish-Protestant descent in Australia with their view that to be Irish in Australia was to be Catholic, and that to be Catholic was to be Irish.

Moran had done much during his rule in Sydney to convey to his flock the significance of their distinctly Irish-Catholic spiritual heritage: ‘I find that the faithful entrusted to my spiritual charge have the same piety, the same love for religion, the same generosity and spirit of sacrifice which distinctly mark the old Church at home.'

When John Fitzgerald Kennedy, a Catholic and a great-grandson of Irish immigrants, was elected president of the United States in 1960, the event was hailed by the Irish in Ireland, and by the huge number of descendants of Irish-Catholic immigrants in America, as a political apotheosis.

However, decades earlier the Irish in Australia had also enjoyed great political success. In 1929 Australians, by electing the Australian Labor Party to power, brought James Scullin to the office of prime minister, both of whose parents were Irish-Catholic immigrants.

In the 1930s and 1940s another three prime ministers, all of whose direct antecedents were of Irish-Catholic stock, were also elected to power: Joseph Lyons (1931–39), John Curtin (1941–45) and Ben Chifley (1945–51).

None of these leaders traded much upon their Irish background, although all had supported the right of Ireland to independence, preferably within the British Empire and Commonwealth.

Scullin and Lyons both visited Ireland and were thanked officially by the government of the Irish Free State for their support in the struggle for independence. Curtin, as an Australian, thought the claims of his Irish ancestry bogus, but as a socialist he certainly defended Ireland’s right to independence.

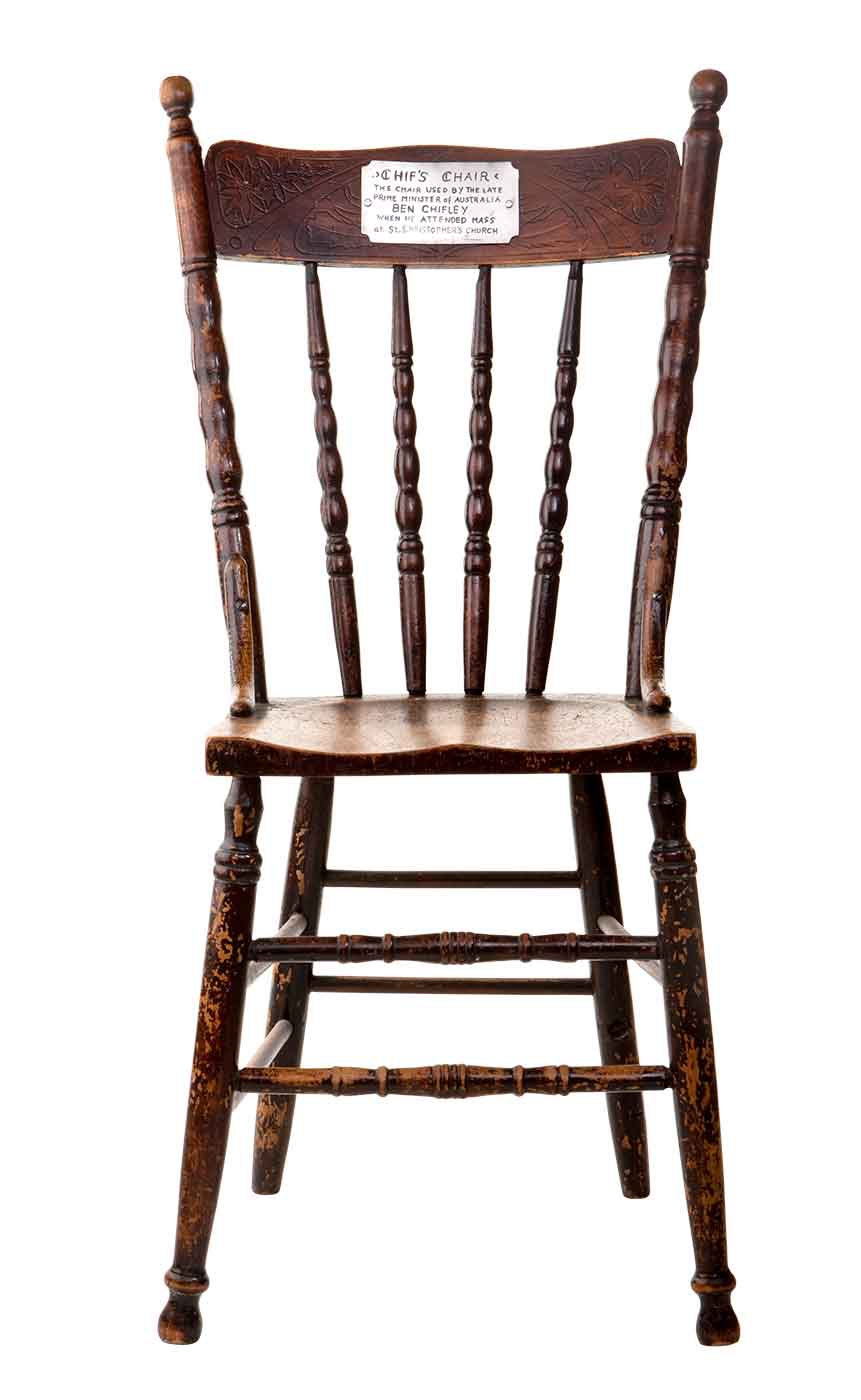

Of the four of them, the one most caught in the trammels of Catholic Australia was Ben Chifley. In 1914 he married a Presbyterian in a Presbyterian church, thereby, under Catholic church law, excluding himself from the sacrament of communion. When he was in Canberra, however, he often attended mass at St Christopher’s Cathedral and sat in a special chair at the back that became known as ‘Chif’s Chair’.

Second-generation Irish Catholics gained positions of supreme national leadership in Australia well before it happened in the United States.

As the 20th century wore on, old hostilities began to fade – especially after the Japanese threat to the nation during the Second World War, which helped to unite Australians across previously denominational and ethnic boundaries.

Interest in such matters as Irish reunification, a cause espoused by prominent Irish leader Éamon de Valera during a nationwide tour in 1948, was negligible. Patrick O’Farrell even entitled an analytical article on this visit, ‘Irish Australia at an End’.

Postwar migration from Catholic countries other than Ireland began a process whereby the hold of the Irish in the Catholic Church began to erode, a process that the growth of an Australian-born priesthood had foreshadowed even before the war.

Today’s Irish immigrants are few in comparison to the large numbers in previous centuries and could not hope to have the same formative influence on Australian society as their predecessors.

But some have made a name for themselves with significant contributions to the nation’s cultural and social life. One such is Claire Dunne, who co-starred in the film made from John O’Grady’s whimsical story of ethnic Australian social mores, They’re a Weird Mob. Dunne went on to be the founder, under the Whitlam government, of the ethnic radio stations 2EA and 3EA.

Old divisions over Ireland rumbled on, however, throughout the 1950s and 1960s. In particular, Australian governments under Sir Robert Menzies were unwilling to recognise the claim of the Dublin-based government of the Republic of Ireland to jurisdiction over the whole country, including the 6 counties of Northern Ireland, which were still an integral part of the United Kingdom.

But in 1963, when Menzies brought in a form of state aid to Catholic schools and then, 2 years later, appointed a full-time Australian ambassador to Ireland, he was perhaps signalling an end to those issues about Ireland and religion that for so long had divided Australians.

Politics perhaps played a part, since the Catholic vote, long seen as being more likely to favour the Australian Labor Party, was now just as likely to be given to more conservative parties.

Over the past 30 years, native-born Australian engagement with Ireland has largely been with the cultural aspects of an Irish heritage. Television mini-series such as Against the Wind, Brides of Christ, The Harp in the South and The Last Outlaw brought the stories of Irish Australia to a wide popular audience.

The nationwide family history movement grew strongly in the 1980s and put many in touch – some for the first time – with the reality of their ancestors’ Irish background and their journey to Australia. This was made possible by the generally excellent Australian archival records. A dedicated few have even taken up Irish language classes.

Following the folk music revival in both Ireland and Australia in the 1950s and 1960s, Irish traditional music of all kinds has become a significant part of the Australian folk music scene, and recent scholarly efforts have begun to unravel the connections between Irish and Australian music.

From about the 1980s being Irish became almost fashionable in Australia, and by the 1990s the international phenomenon of the ‘Irish pub’ took hold in Australian capital cities.

The historical significance of the large Irish presence in Australia in former times, however, seems almost forgotten except by a few researchers. Only on one day of the year are the Irish clearly visible to all – St Patrick’s Day.

St Patrick’s Day activities in Australia have mirrored the changing nature of Irish Australia. In the early years of the penal colony of New South Wales, convict workers, hungover from the excesses of the patron saint’s festival, were remarked upon by their British gaolers.

During the middle years of the 19th century, the day was often celebrated with community dinners and lengthy speeches, and was attended by Irish and non-Irish alike.

After the Fenian scare of 1868, St Patrick’s Day celebrations often took the form of large picnics with music, dancing, and semi-serious sporting activities (such as the tug-of-war). In Sydney, by the 1880s, street marches were held. But by this stage the day was definitely an Irish-Catholic occasion.

In the mid-1890s Cardinal Moran, feeling that the event was too closely associated with loud, unedifying activities that tended to strengthen prejudices about Catholics, took matters into his own hands. He developed Sydney’s St Patrick’s Day as a ‘national festival’ to be celebrated by appropriate religious ceremonies in the cathedral, Catholic school athletic demonstrations at the showgrounds, a vice-regal lunch and a formal concert in the Town Hall.

In the crisis years of 1916–22 St Patrick’s Day parades in Melbourne under Archbishop Mannix were assertive political statements of Catholic loyalty to Australia during the war and support for the cause of Irish independence.

During the 1930s in Sydney, with Irish-born archbishop Michael Kelly supervising affairs, the parades had no such Irish political content: instead, floats displaying stories of early Catholic Sydney or St Patrick himself, surrounded by round towers, harps and Celtic crosses, took centrestage.

After the Second World War, however, the city’s observance of St Patrick’s Day amounted to little more than special religious services, an evening concert and school sports displays at the showgrounds.

For as long as Mannix was alive, the Melbourne parade continued, but it ceased altogether in 1970. Could this perhaps be explained by a growing sense among a generation of postwar Catholics, as sectarian antipathies slowly evaporated, that these public displays of Irish ethnic origins carried less and less meaning for them as Australians?

The parade experienced a rebirth in Sydney in the late 1970s, and a patchy revival in Melbourne, organised by Irish ex-pats as a fun day of celebration and fancy floats with an Irish cultural emphasis.

Virtually absent was any reference to previous Irish-Australian stories and that sense of Catholic self-assertiveness characteristic of earlier parades. It all seemed very much part of a new multicultural Australia, of which the modern Irish were simply one more colourful component.

One Melbourne organiser unwittingly provided an epitaph for the old-style Australian St Patrick’s Days: ‘It is a great day for the Irish, the English, the Vietnamese, the Cambodian and everyone else who cares to come to the party.'

Nevertheless, St Patrick’s Day remains the Irish day in Australia. The statements of today’s parade organisers might show little understanding of the complexities of an Irish-Australian past stretching back to 1788, but through all the shenanigans – green beer, dyed hair and T-shirts bearing ‘Kiss me I’m Irish’ slogans – a question still lingers in the air: ‘What has it meant to be Irish in Australia?’

The objects and stories assembled here do not provide a simple answer to that question, but rather show just what a remarkable and rich story Australia has inherited from a past where the Irish were among the stars of the show.

This essay by Richard Reid appeared in the National Museum of Australia’s publication, Not Just Ned: A True History of the Irish in Australia.

You may also like