36°18’00” South 150°02’00” East

James Cook, 21 April 1770:

At 6 oClock we were a breast of a pretty high mountain laying near the shore which on account of its figure I named Mount Dromedary.

Djiringanj Yuin knowledge-holder Warren Foster explains the sacred significance of Mount Gulaga and shares his ancestors' view from the shore when James Cook sailed past his country. Produced by the ABC in partnership with the National Museum of Australia. View transcript

Gulaga has always been a sacred mountain for the Yuin people of southern New South Wales. Unaware of this, Cook renamed the distinctive hump-shaped landform ‘Mount Dromedary’ as he sailed up the coast.

Patricia Ellis, Yuin Elder:

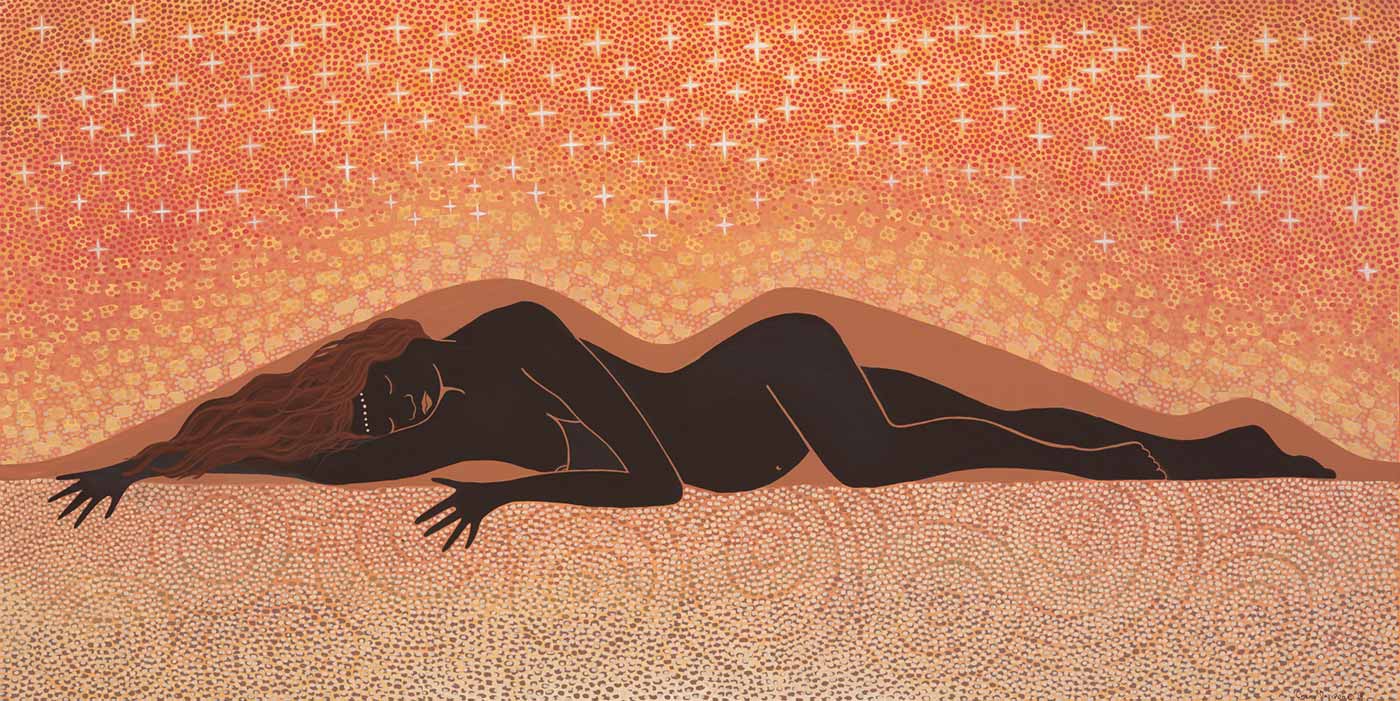

Captain Cook looked at the mountain and he saw a camel. Aboriginal people look at Gulaga and we see a woman who is reclining.

Mother Mountain

Yuin people know Gulaga as Mother Mountain. It is an important women’s place, linked to ceremony, childbirth and storytelling.

Cheryl Davison, Walbunja/Ngarigo:

She’s always been here Gulaga is the Mother Mountain. Pregnant, she lies on her side, her head to the south, her feet to the north, facing the sea ... She was here when the stars and the moon and everything else was created ... she’s always been here.

The Gulaga story

Cheryl Davison, Walbunja/Ngarigo:

One day Gulaga and her two sons, Baranguba and Najanuga, were collecting bush tucker. When Baranguba asked if he could go fishing, Gulaga said, ‘No, you’re too young, you’re to stay next to me’.

As they walked along, Baranguba insisted that he go fishing. But Gulaga said, ‘No, no, you have to stay next to me, it’s not safe to go fishing by yourself’. But Baranguba snuck away. He made himself a canoe and he rowed out to sea, where a big wave came and washed him off the canoe ... He laid down in the water — and that’s where he still lives today.

When Najanuga, the younger son, saw this, he wanted to move away and set up his own camp. But Gulaga said, ‘No, you’re too young, you just sit here right next to me’.

So now she lies there, looking out at the sea at her older son, with her younger son right next to her, in arm’s reach.

Wallaga Lake Reserve

European squatters and timber cutters came to the area around Gulaga from the 1830s, pushing Yuin people off their land. In 1891 colonial authorities established the first Aboriginal reserve in New South Wales at Wallaga Lake, in the shadow of Gulaga.

Many Yuin people with links to Gulaga were forced to live there, under the eye of a non-Aboriginal manager. For people from here, the stories of these times are part of the Cook story.

Life on the reserve

Yuin Kelly, Yuin:

I remember a welfare woman coming some days and saying, ‘Where’s your daughter?’ And Mum would have me hiding in the food cupboard.

Reserves could be harsh places. Speaking in language was banned, traditional culture discouraged, entering and leaving the reserve was controlled, and children could be removed from their families. Despite these intrusions, family life and culture continued.

Today, Aboriginal families living at Wallaga Lake have mixed memories of the old life on the reserve.

Endeavour Voyage 19 Jun 2019

Life on the reserve

Yuin Kelly, Yuin

The manager’s wife used to come around and check all the houses and see if they were all clean and, the biggest scariest part was the welfare though, eh, ’cos that meant something more serious and yeah.

Mum was smart like, all the other women and mums back in the days on protecting us, though we were under the Protection Board, our mums were the true protectors, our dads, our uncles, our aunties, grandparents. So, Mum would always think ahead of the welfare. I remember, a welfare woman coming, some days and, ‘Where’s your daughter?’ and Mum would have me hiding in the food cupboard behind the Pick-Me-Up sauce and the bit of flour and white sugar.

Other times when the welfare would come in, this is on Wallaga, Mum would say, ‘Run down the track there. There’s a big log down there, a big tree down there. Go down there and hide’. And I’d run down and there’d be other children there hiding too.

Lorraine Naylor, Yuin:

In the early time when I was really small, because Wallaga Lake had its own little school, and we went to school here up until we got to Sixth Class and then we went to Bermagui Public, ’cos we got a bit too big.

Because the teacher from, at Wallaga Lake, was the manager’s wife and she didn’t know anything. She wasn’t a qualified teacher, so, all we used to learn, you know, just learn a few maths with blocks and play with blocks and make handkerchiefs and make aprons.

Eric Naylor, Kamilaroi:

We used to go fishing every day, we used to go rabbiting ... just about every day ... spearing fish. We had that much to do, you know, we were never bored. And yeah, it was good growing up here in Wallaga.

You know years ago you used to be able to walk into a house, any house on Wallaga, help yourself to a cup of tea and a bit of damper ’cos that’s the way it was. And the old people was very, very strict and you had to be inside before dark. If you weren’t they come looking for you.

Making do

Lorraine Naylor, Yuin:

Because we didn’t have electricity ... we had fat lamps.

In the early years people living on the reserve lit their homes with lamps they made from empty tins and animal fat. Electricity was only connected at Wallaga Lake in 1955.

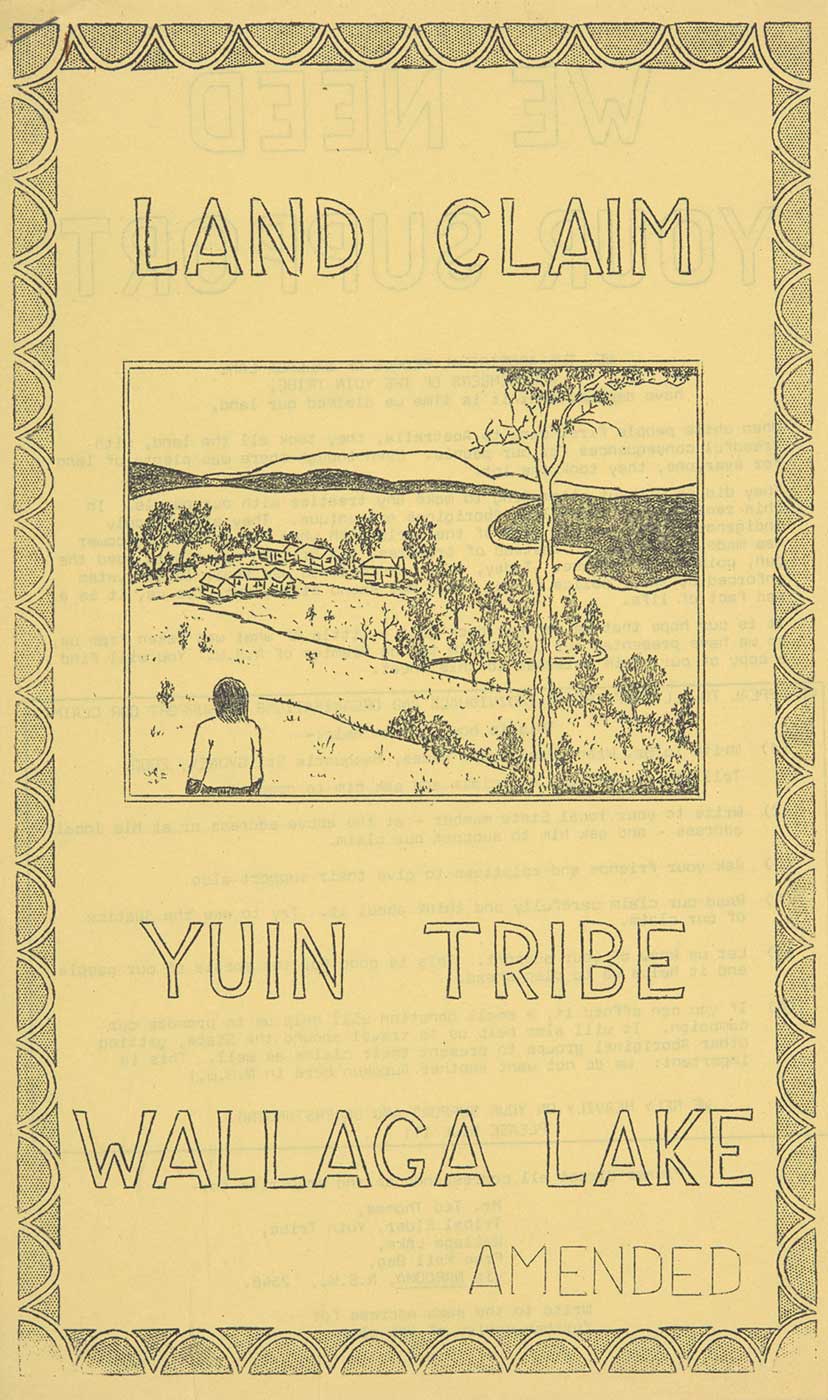

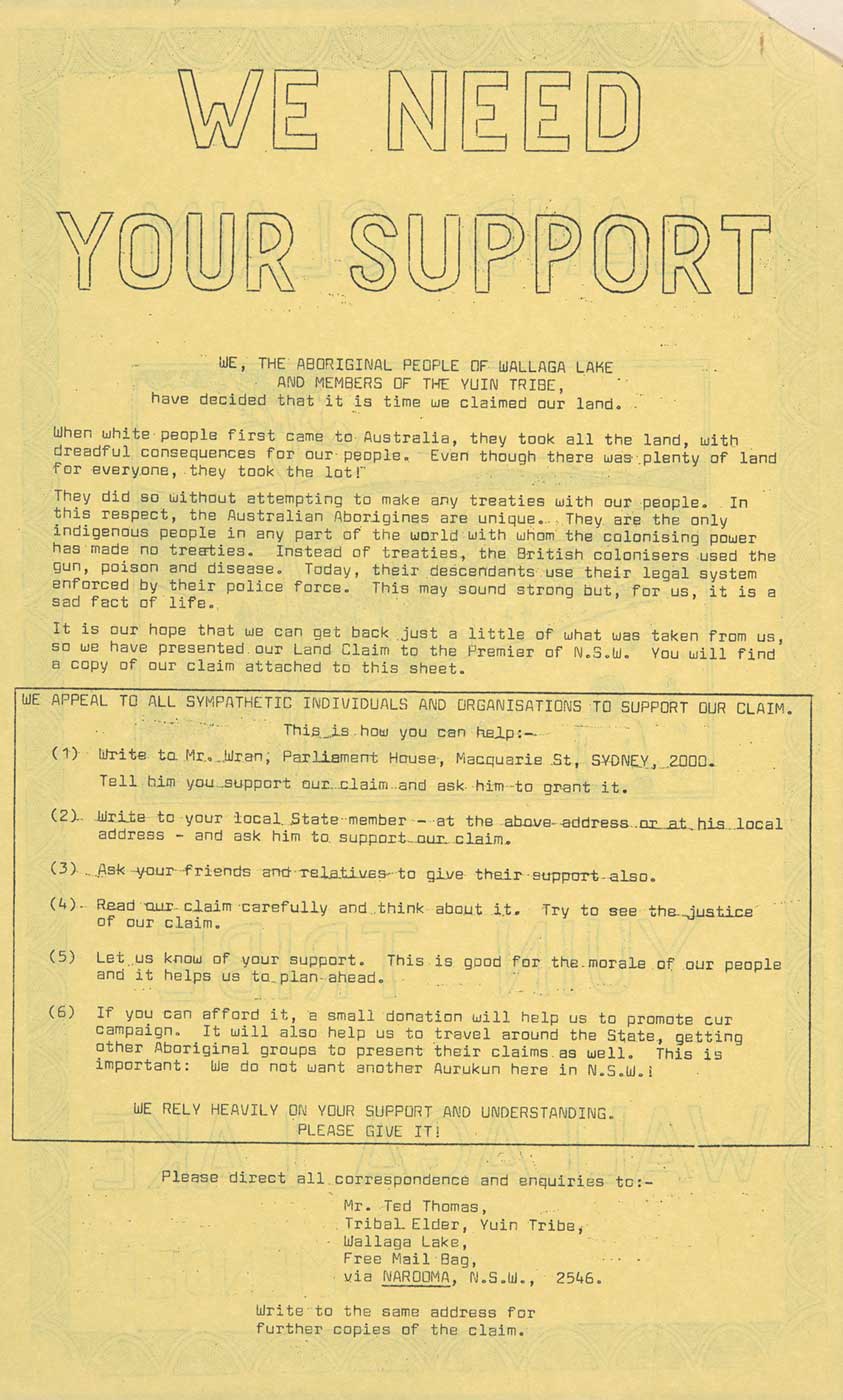

Getting Wallaga back

In 1978, Yuin people from Wallaga Lake presented a claim for their land to Neville Wran, Premier of New South Wales. They wrote:

When the white people came ... they took our land from us, using the gun, poison and disease to help them. It was then ... that terrorism first came to these shores!

The community acquired the title deeds to the Wallaga Lake reserve in 1984.

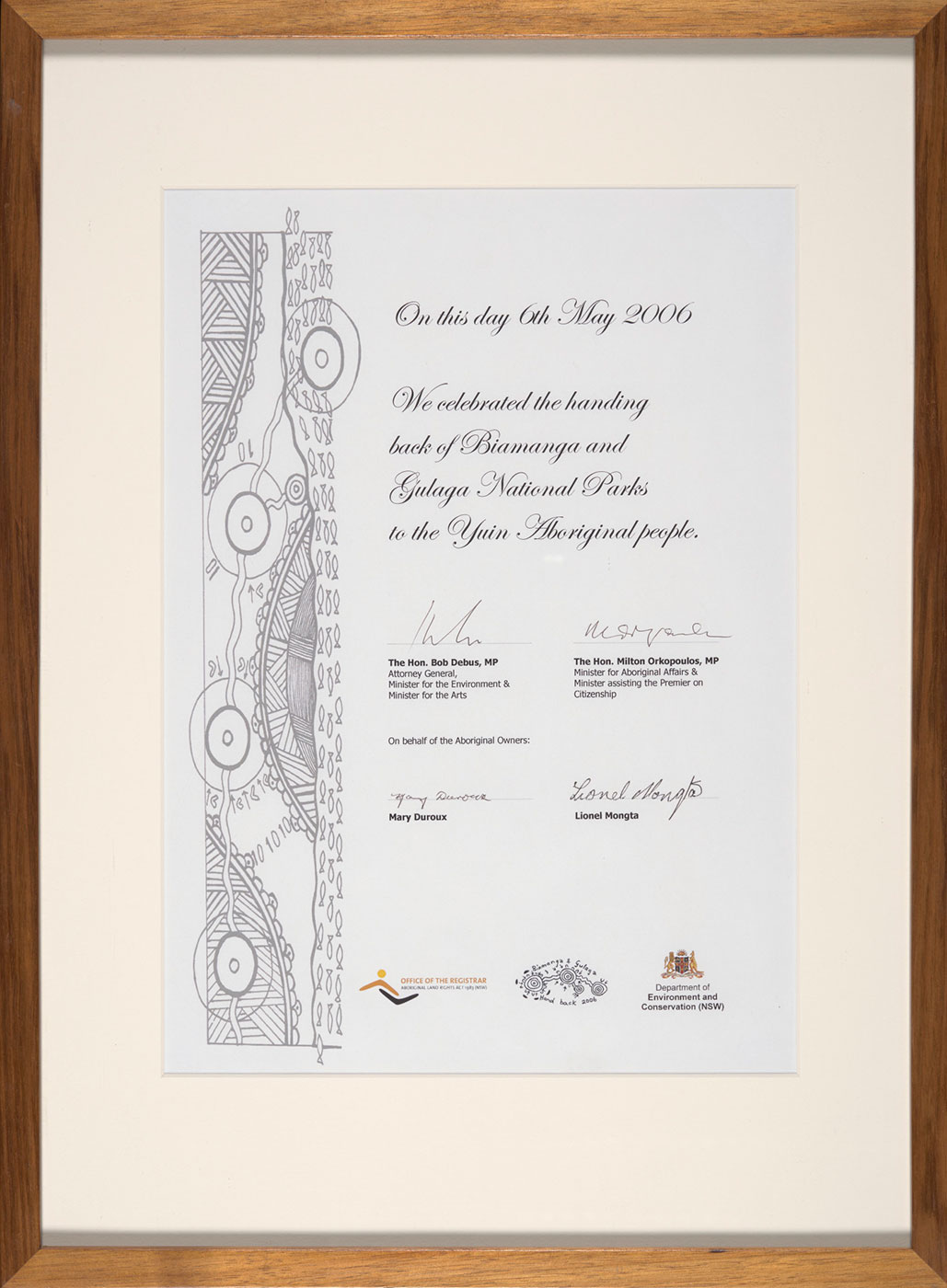

Reclaiming the mountains

Iris White, Yuin:

This place is not just my physical home, it’s also my spiritual home ... We were encouraged to step up ... to look out for Gulaga in the same way she has looked out for us.

Yuin people began protesting against logging on Gulaga in the late 1970s. As logging intensified, Yuin elders made claims to have Gulaga and nearby Biamanga recognised as Aboriginal sites of significance. Both were handed back to Yuin people in 2006.

Education resources

These resources cater for students in Years 3 to 6 and all activities align with the Australian Curriculum. Years 3 and 4 align with the history content and Years 3 to 6 align with the cross-curriculum priority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures.