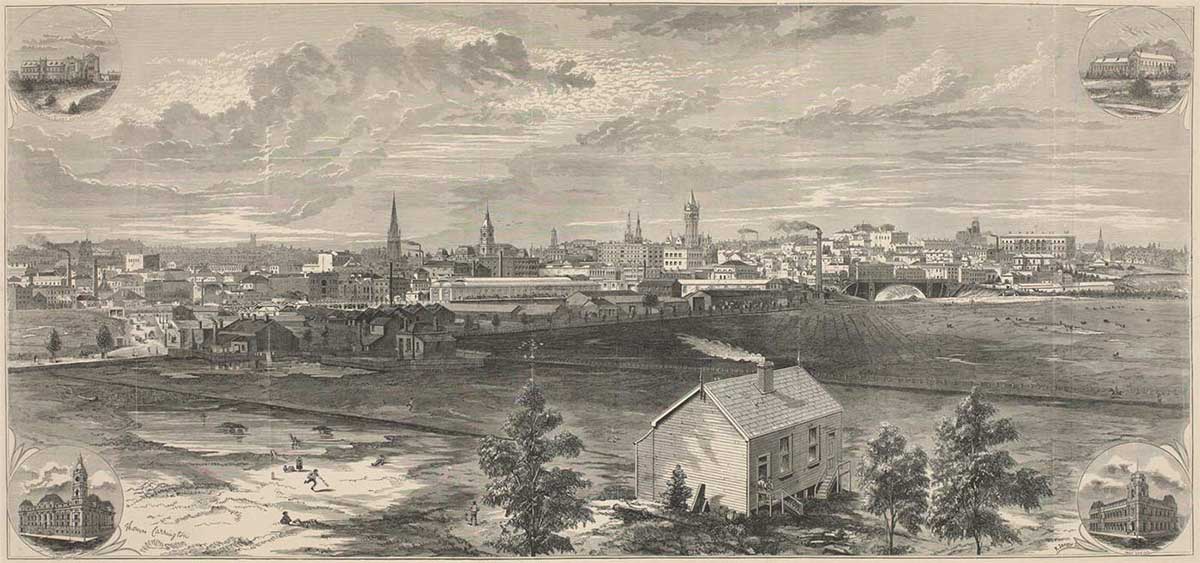

This wood engraving shows a view of Melbourne from Emerald Hill on the south side of the Yarra River, looking to the north-east, about 1875. The artwork was created by Thomas Carrington and engraved by Rudolph Jenny. It was published as a supplement to the weekly Melbourne paper, The Australasian.

Panoramic images of cities and country towns were a popular way of showing the rapid progress of colonial society.

Essence of everyday life

In addition to showcasing the architecture of Melbourne, the artist has captured the essence of everyday life in the expanding city.

On close examination, the wood engraving unveils tiny details of people going about their daily activities, for example, a family watching a cricket match, a well-dressed couple strolling along the riverbank, and various riders on horseback.

Rapid growth of Melbourne

By the 1860s Melbourne was booming as wealth flooded in from the goldfields. Timber structures, for example the Town Hall and the General Post Office, were replaced by substantial stone buildings. Tree stumps and potholes were removed from the streets, and new suburbs constructed to house the growing population.

The rapid growth of Melbourne attracted skilled workers to the city, including artists, engravers, journalists and printers. By the 1880s, 'Marvellous Melbourne', as the town came to be known, was the second largest city in the British Empire.

Illustrated newspapers in Australia

The introduction of imagery to the press began in the 1830s with overseas publications such as The Penny Magazine, Punch and the Illustrated London News.

Early attempts at publishing an illustrated paper in Australia had mixed results. Competition, combined with expensive production methods and a limited audience, meant many early illustrated papers were economically unviable.

By the late 1850s Melbourne was the hub of the printing industry in Australia, supporting two daily newspapers, The Argus and The Age. The circulation of these daily newspapers provided the capital required to produce the time-intensive illustrated issues.

The two most successful illustrated papers in Australia were the Australasian Sketcher (1873–1889) and the Illustrated Australian News (1862–1896). Both papers had the backing of sister publications, The Argus (1846–1857) and The Age (1854–) respectively.

Thomas Carrington's panorama of Melbourne was published as a souvenir supplement to the weekly paper, The Australasian, also a subsidiary of The Argus.

Newspapers were the major way people learnt of events from around Australia and the world. The offices of The Argus and The Age became a focal point of Melbourne society, with crowds often gathering outside to be the first to read the latest news.

Woodblock engraving

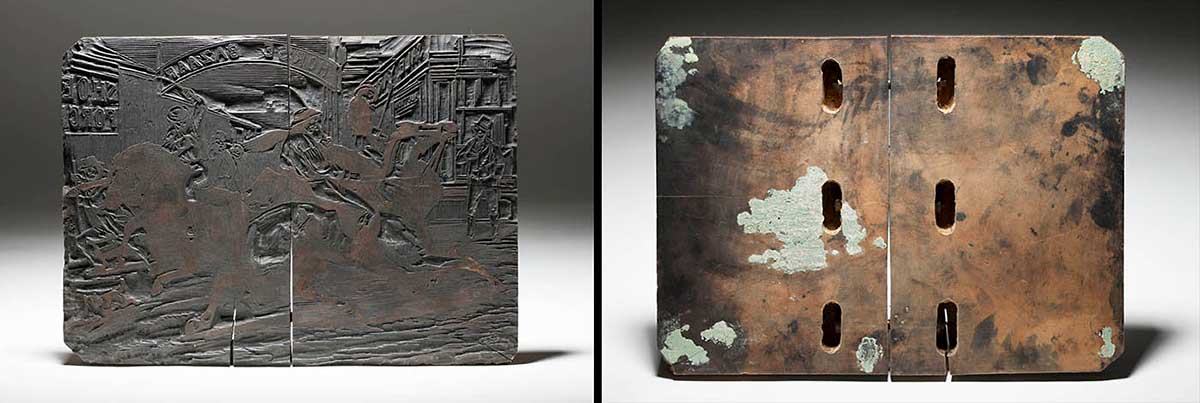

During the mid- to late 1800s, the main way to reproduce detailed images in a newspaper was to create a wood engraving.

This labour-intensive process began with an artist's sketch, which was copied in reverse on to the end grain of a hardwood block. Next, an engraver carved the image into the surface of the wood, using tools called burins or gravers, to creating a detailed relief design.

The raised surface became the black areas of the final print and the engraved lines appeared white.

An average size illustration, 200 x 250mm, could take up to three days to complete. For large illustrations multiple blocks were engraved, then joined together to form the complete image. The advantage of using wood engravings was that they were hard and durable and could withstand large print runs without loss of quality.

The blocks were machined to the same height as moveable type, to allow for printing on letterpress printing machines. Many woodblocks were burnt after they had been printed as they could not be reused, and are now very rare and hard to find.

Artist and engraver

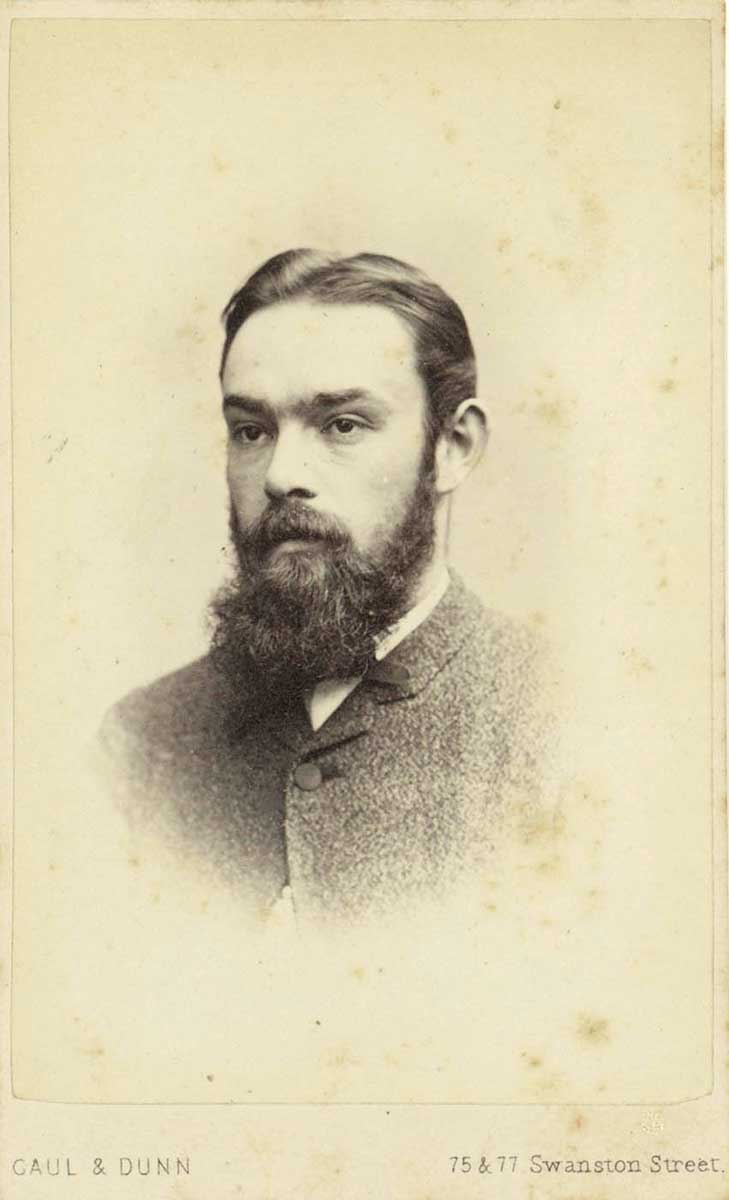

Thomas Carrington was born in London in 1843 and studied at the South Kensington School of Art. He arrived in Victoria in the early 1860s hoping to find his fortune on the goldfields.

Unsuccessful, he later settled in Melbourne, where he became renowned for his illustrations and political cartoons.

He began a long association with Punch and in 1873, became the senior artist for The Australasian Sketcher.

Rudolph Jenny was a prolific engraver for many of the illustrated periodicals published in Melbourne.

He emigrated from Switzerland about 1855 and by the early 1860s was employed by well-known engraver, Frederick Grosse. He continued to work as an engraver until the 1890s.

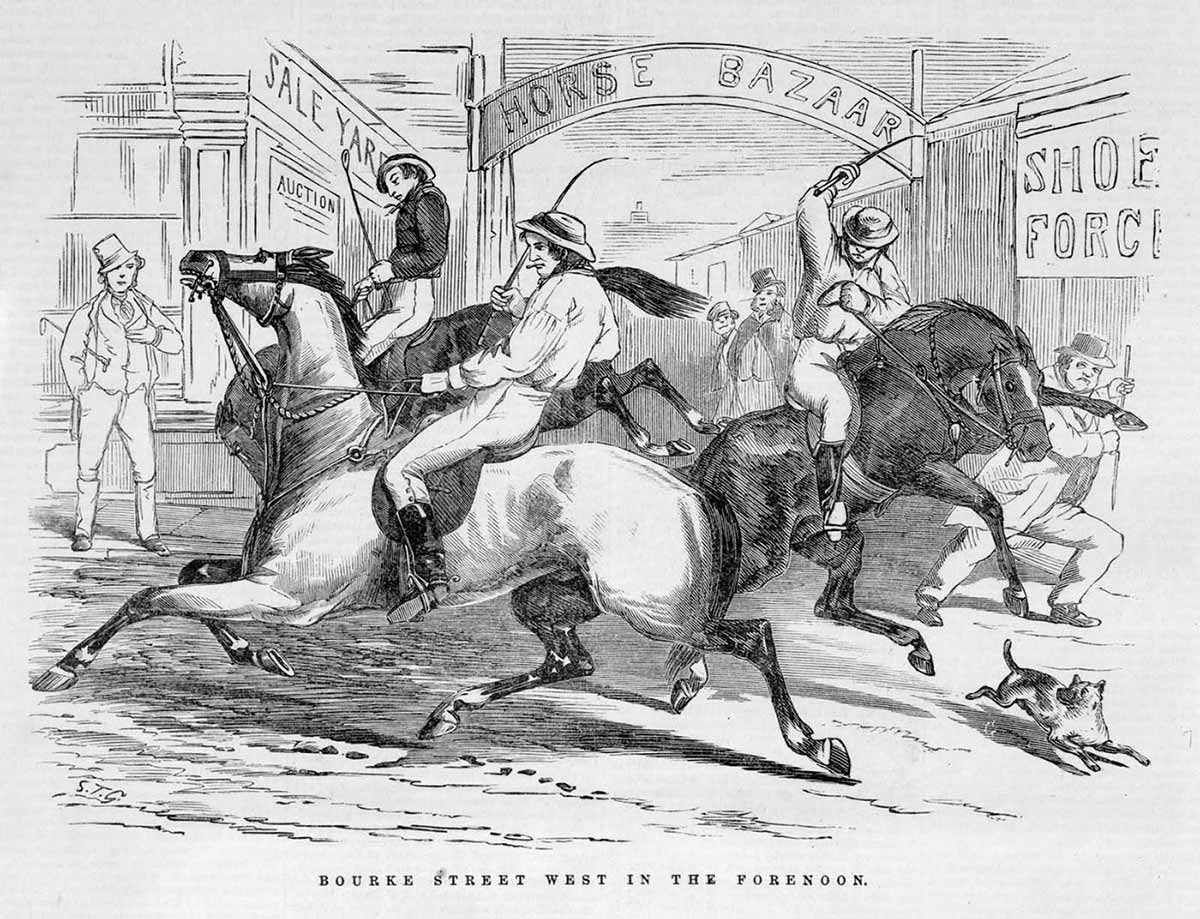

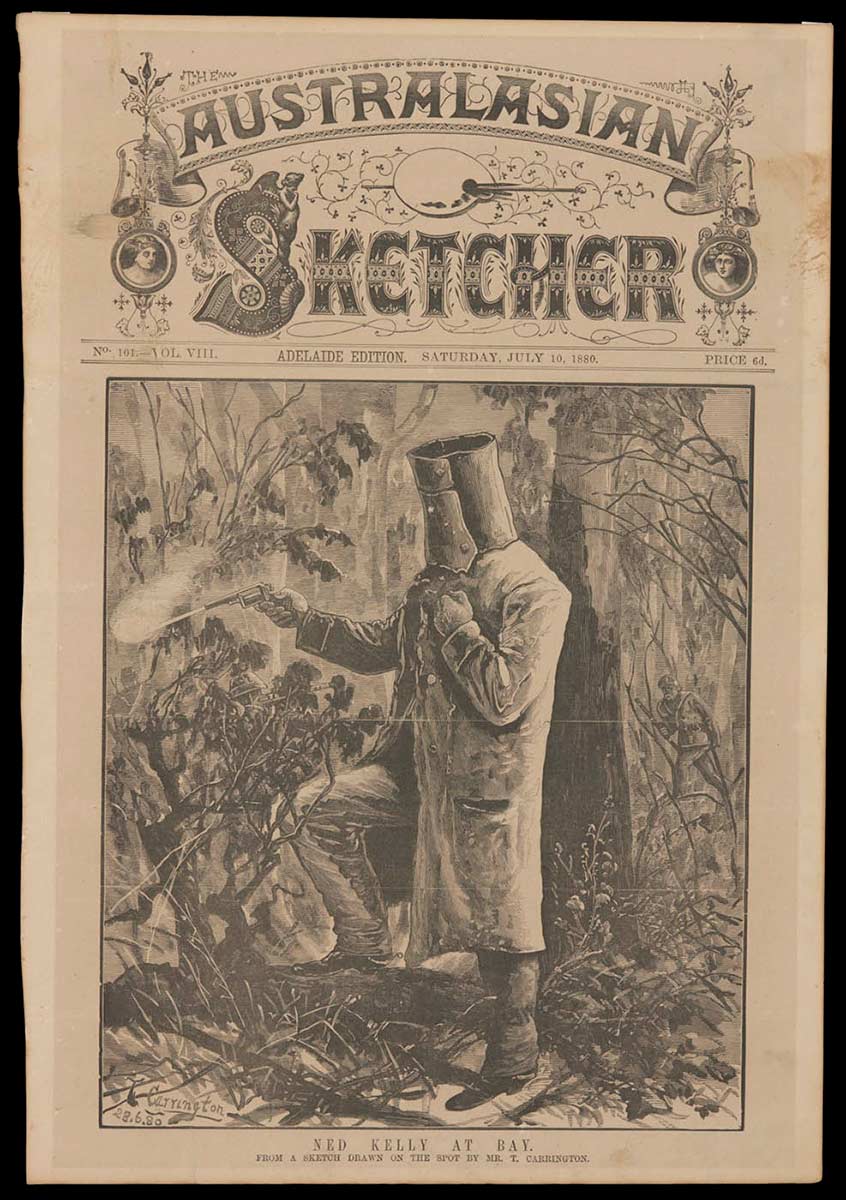

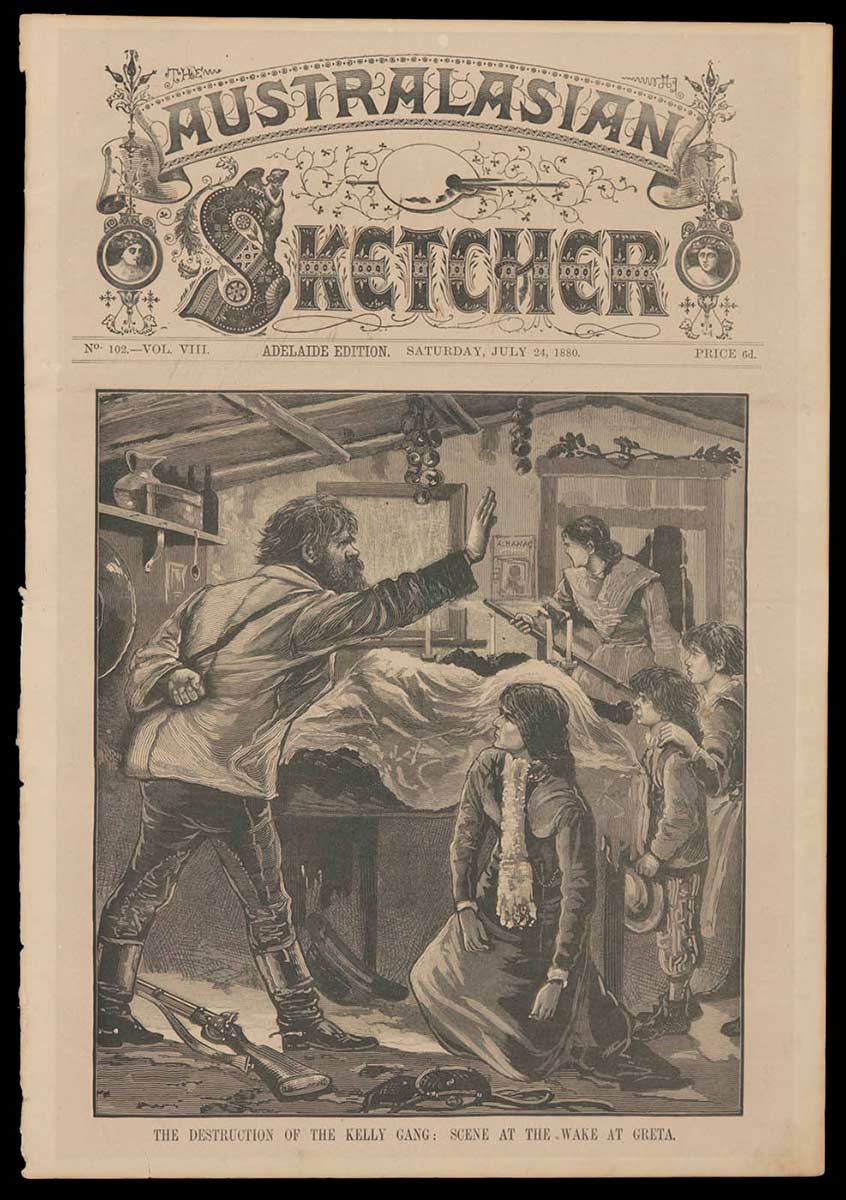

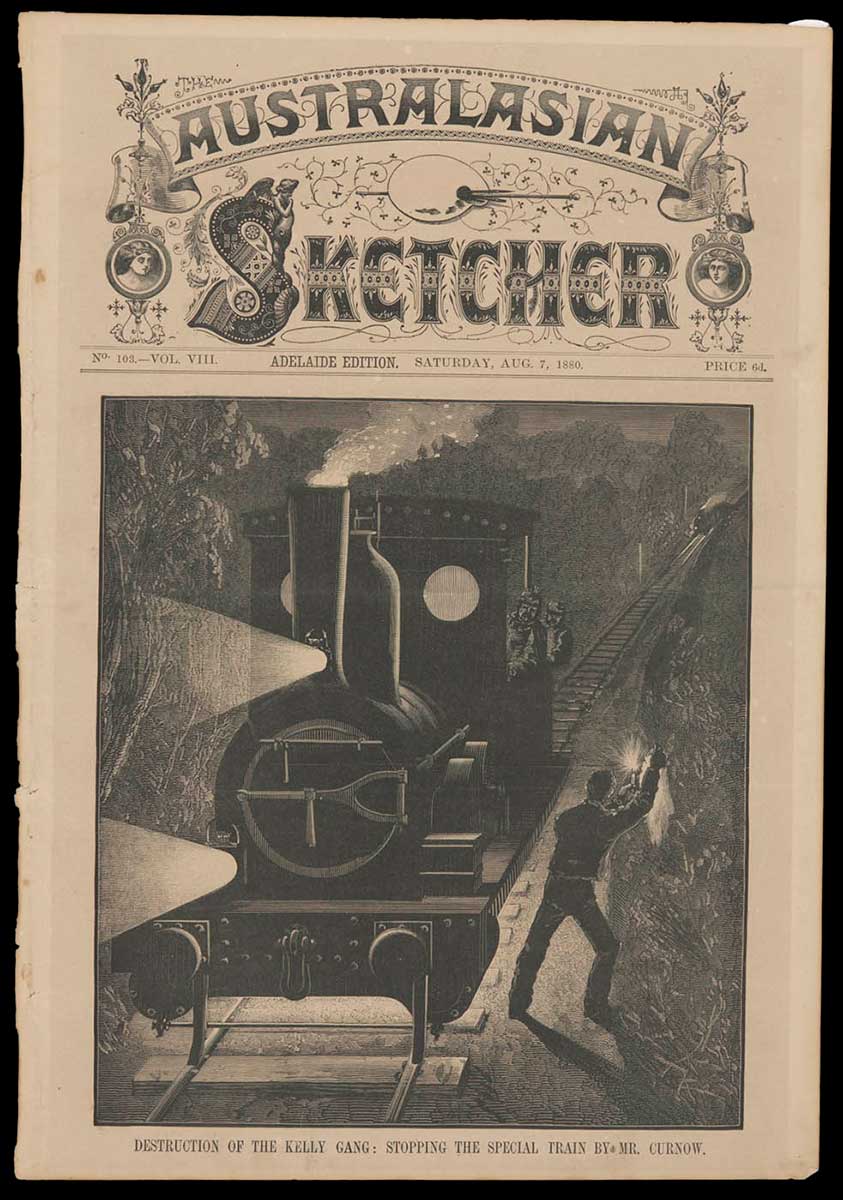

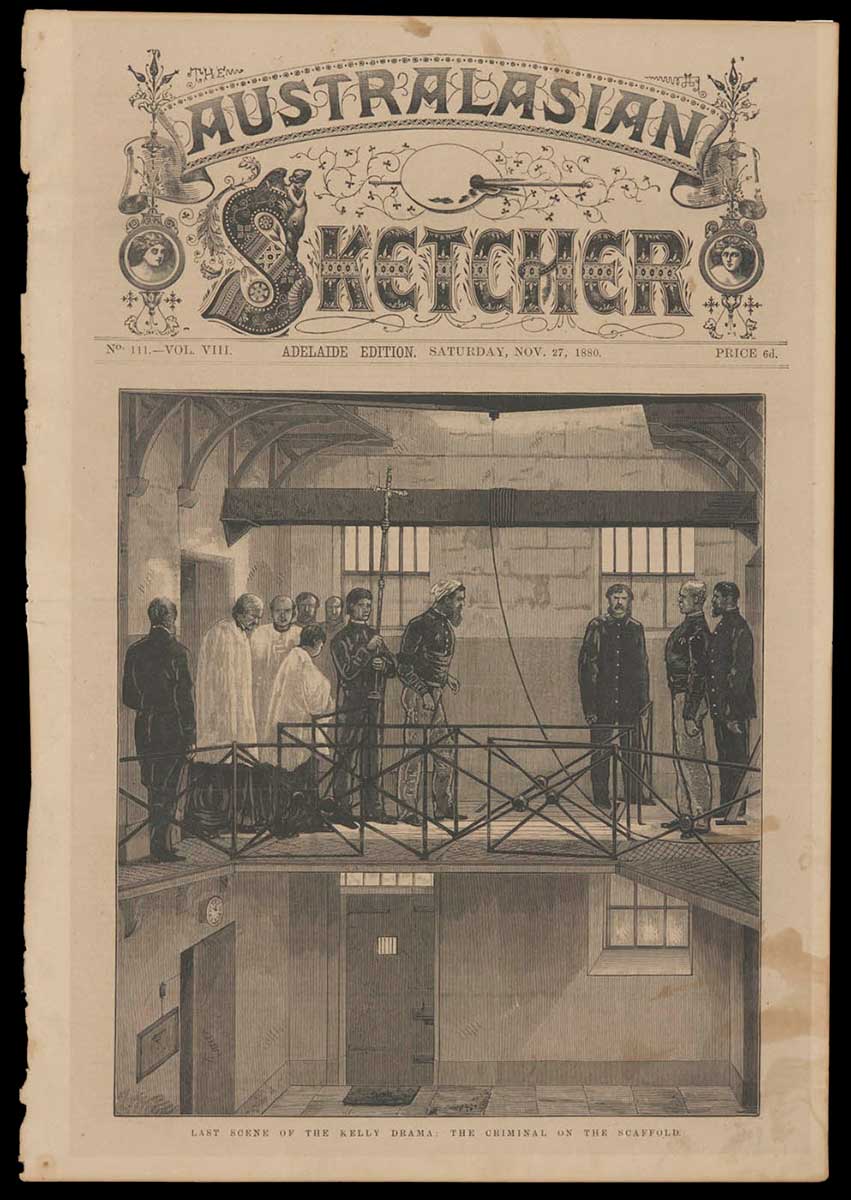

Carrington's Ned Kelly covers

The Museum's collection also includes a series of Australasian Sketcher covers from Thomas Carrington depicting the events of bushranger Ned Kelly's capture, trial and hanging in 1880.

In 1880 it was unusual for the press to be at the scene of events as they unfolded. Carrington was alerted to the situation developing at Glenrowan in Victoria, and was permitted to travel on the special police train to the scene. Photographers were not allowed on the first train due to the bulky equipment they carried.

The public still had to wait five days to see the first images appear in the press as the process for reproducing illustrations as wood engravings was so time consuming.

End of an era

The time of illustrated newspapers was however, destined to be short. Advances in printing technology in the late 1880s enabled the reproduction of photographs as halftone images.

The popularity of woodblock engraving declined rapidly, superceded by the speed and accuracy of photographic images. The photographer could capture events as they happened whereas the artist used imagination and artistic licence to create the illustration.

In our collection

References

Graeme Davison, Marvellous Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, Victoria, 1978.

Peter Dowling, Chronicles of progress: The Illustrated Newspapers of Colonial Australia, 1853–1896, Monash University, Victoria, 1997.

Peter Dowling, 'Destined not to survive: The illustrated newspapers of Colonial Australia', Studies in Newspaper and Periodical History, 1995 annual, 1997.

Peter Dowling, 'Truth versus art in nineteenth-century graphic journalism: The colonial Australian case', Media History, vol. 5, no. 2, 1999.