On 16 February 1911 many workers at the Sunshine Harvester Works laid down their tools and went out on strike. Aiming to create a united workforce that could demand better wages and conditions, the strikers called on the works’ owner, HV McKay, to dismiss non-union labour. But McKay vowed that unionists would never control his factory and locked unionised workers out.

The Sunshine Harvester Works was at the time one of the largest factories in Australia and a focus for contest over industrial relations. The strike brought to a head years of dispute over working conditions, the power of trade unions, and the government’s right to dictate how much employers should pay their workers.

Timeline

Hear from the participants and follow the events of the 1911 strike.

On 22 January Melbourne members of the Agricultural Implement Makers’ Union (AIMU), including many from the Sunshine Harvester Works, gathered at a mass meeting. The unionists had tried to better their wages and conditions through lobbying government and arguing their case in the conciliation and arbitration court, but had met with little success. They now believed that a strike was the only way to achieve their goals.

The AIMU decided that all workers in the agricultural implements trade in Melbourne had to join the union if they were to have any power. They announced ‘that all non-unionists be given three weeks opportunity to join the union, failing which the executive advises unionist members to refuse to work with them’.

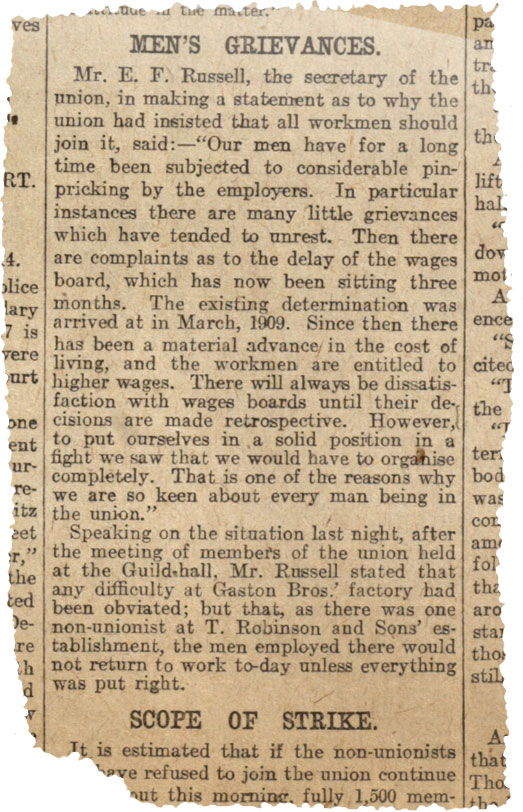

Excerpt from the Melbourne Argus, 16 February 1911

Transcript

MEN'S GRIEVANCES.

Mr. E. F. Russell, the secretary of the union, in making a statement as to why the union had insisted that all workmen should join it, said:— "Our men have for a long time been subjected to considerable pin-pricking by the employers. In particular instances there are many little grievances which have tended to unrest. Then there are complaints as to the delay of the wages board, which has now been sitting three months. The existing determination was arrived at in March, 1909. Since then there has been a material advance in the cost of living, and the workmen are entitled to higher wages. There will always be dissatisfaction with wages boards until their decisions are made retrospective. However, to put ourselves in a solid position in a fight we saw that we would have to organise completely. That is one of the reasons why we are so keen about every man being in the union."

Speaking on the situation last night, after the meeting of members of the union held at the Guild-hall, Mr. Russell stated that any difficulty at Gaston Bros.' factory had been obviated; but that, as there was one non-unionist at T. Robinson and Sons' establishment, the men employed there would not return to work to-day unless everything was put right.

On 14 February the executive of the Agricultural Implement Makers’ Union (AIMU) gathered to consider progress on their call for all Melbourne agricultural implements workers to join the union.

Only 42 workers across Melbourne, including 12 men at the Sunshine Harvester Works, had refused to sign up. The executive decided that it now had the numbers to challenge employers over wages and conditions through a strike.

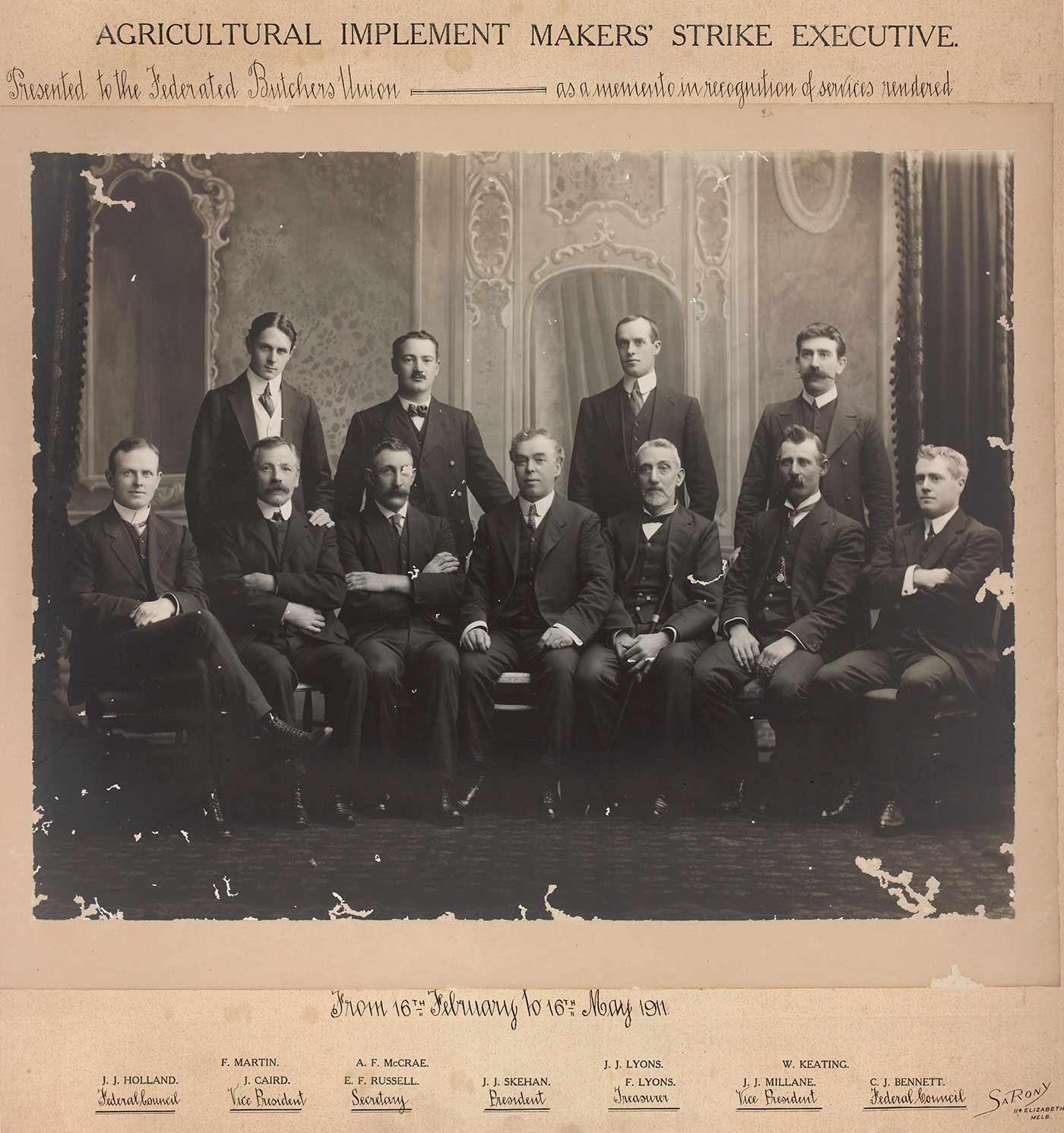

Agricultural Implement Makers’ Strike Executive, 1911

Transcript of inscriptions on photograph mount

Title printed on mount above image: AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENT MAKERS' STRIKE EXECUTIVE

Inscribed below title: Presented to the Federated Butchers' Union as a memento in recognition of services rendered.

Inscribed on mount below image: From 16th February to 16th May 1911.

Photographer's name on bottom right corner of mount: Sarony 114 Elizabeth St. Melb.

Printed identifications below image: top row—F. Martin, A. F. McCrae, J. J. Lyons, W. Keating; bottom row—J. J. Holland (Federal Council), J. Caird (Vice President), E. F. Russell (Secretary), J. J. Skehan (President), F. Lyons (Treasurer), J. J. Millane (Vice President), C. J. Bennett (Federal Council).

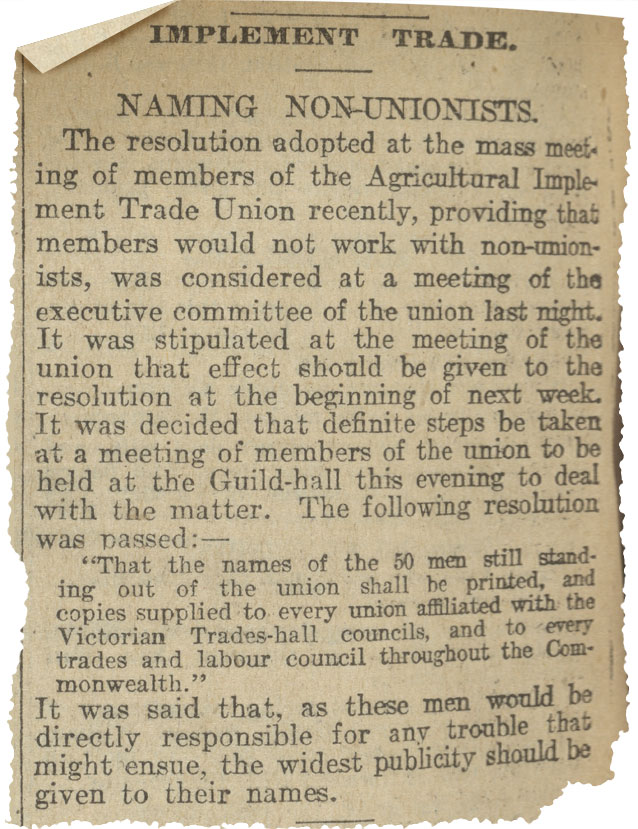

Article from the Melbourne Argus, 15 February 1911

Transcript

IMPLEMENT TRADE.

NAMING NON-UNIONISTS.

The resolution adopted at the mass meeting of members of the Agricultural Implement Trade Union recently, providing that members would not work with non-unionists, was considered at a meeting of the executive committee of the union last night. It was stipulated at the meeting of the union that effect should be given to the resolution at the beginning of next week. It was decided that definite steps be taken at a meeting of members of the union to be held at the Guild-hall this evening to deal with the matter. The following resolution was passed:

That the names of the 50 men still standing out of the union shall be printed, and copies supplied to every union affiliated with the Victorian Trades-hall councils, and to every trades and labour council throughout the Commonwealth.It was said that, as these men would be directly responsible for any trouble that might ensue, the widest publicity should be given to their names.

On 15 February representatives of the Agricultural Implement Makers’ Union (AIMU) visited Melbourne implement manufacturers employing non-unionised labour. Lists of non-union workers were provided to the employers, with an ultimatum that unless these men joined the union that day, there would be a strike.

At the Sunshine Harvester Works, union organiser JM Smith spoke with owner HV McKay. McKay declared that he would not force his workers to join the union, nor allow anyone else to interfere with their freedom to refuse the union. McKay then reported his decision to the works’ shop stewards, employees officially representing the union in the factory.

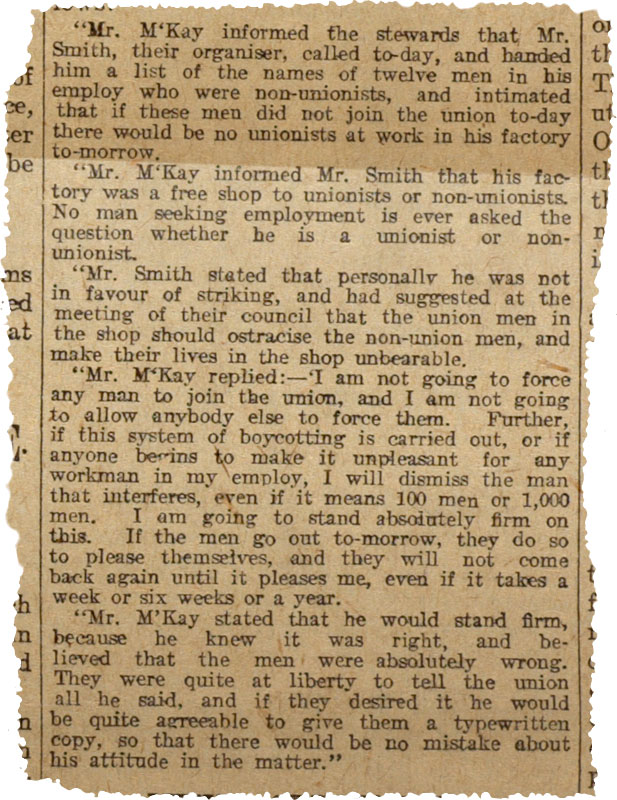

Excerpt from the Melbourne Argus, 16 February 1911

Transcript

"Mr. M'Kay informed the stewards that Mr. Smith, their organiser, called today, and handed him a list of the names of twelve men in his employ who were non‑unionists, and intimated that if these men did not join the union today there would be no unionists at work in his factory tomorrow.

"Mr. M'Kay informed Mr. Smith that his factory was a free shop to unionists or non‑unionists. No man seeking employment is ever asked the question whether he is a unionist or non‑unionist.

"Mr. Smith stated that personally he was not in favour of striking, and had suggested at the meeting of their council that the union men in the shop should ostracise the non‑union men, and make their lives in the shop unbearable.

"Mr. M'Kay replied:— I am not going to force any man to join the union, and I am not going to allow anybody else to force them. Further, if this system of boycotting is carried out, or if anyone begins to make it unpleasant for any workman in my employ, I will dismiss the man that interferes, even if it means 100 men or 1,000 men. I am going to stand absolutely firm on this. If the men go out to-morrow, they do so to please themselves, and they will not come back again until it pleases me, even if it takes a week or six weeks or a year.

"Mr. M'Kay stated that he would stand firm, because he knew it was right, and believed that the men were absolutely wrong. They were quite at liberty to tell the union all he said, and if they desired it he would be quite agreeable to give them a typewritten copy, so that there would be no mistake about his attitude in the matter."

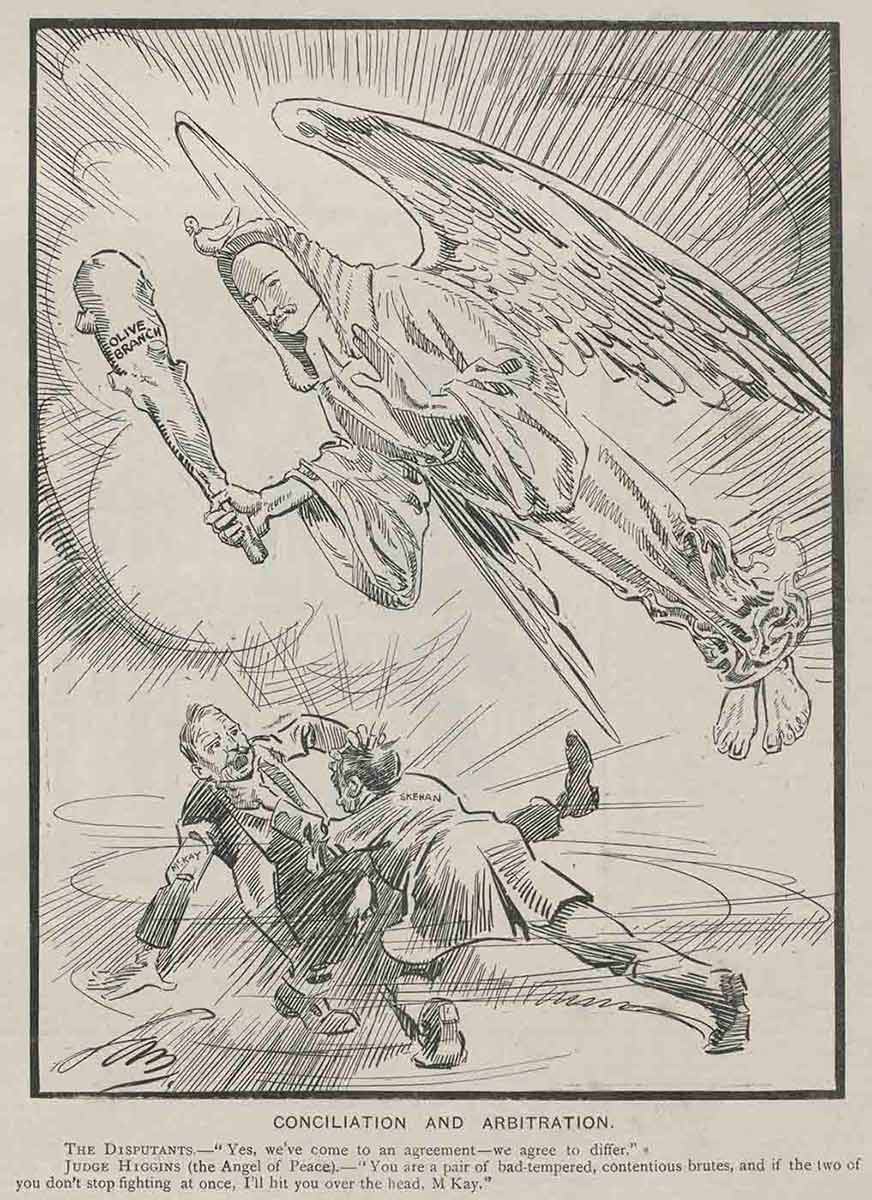

Failure of arbitration

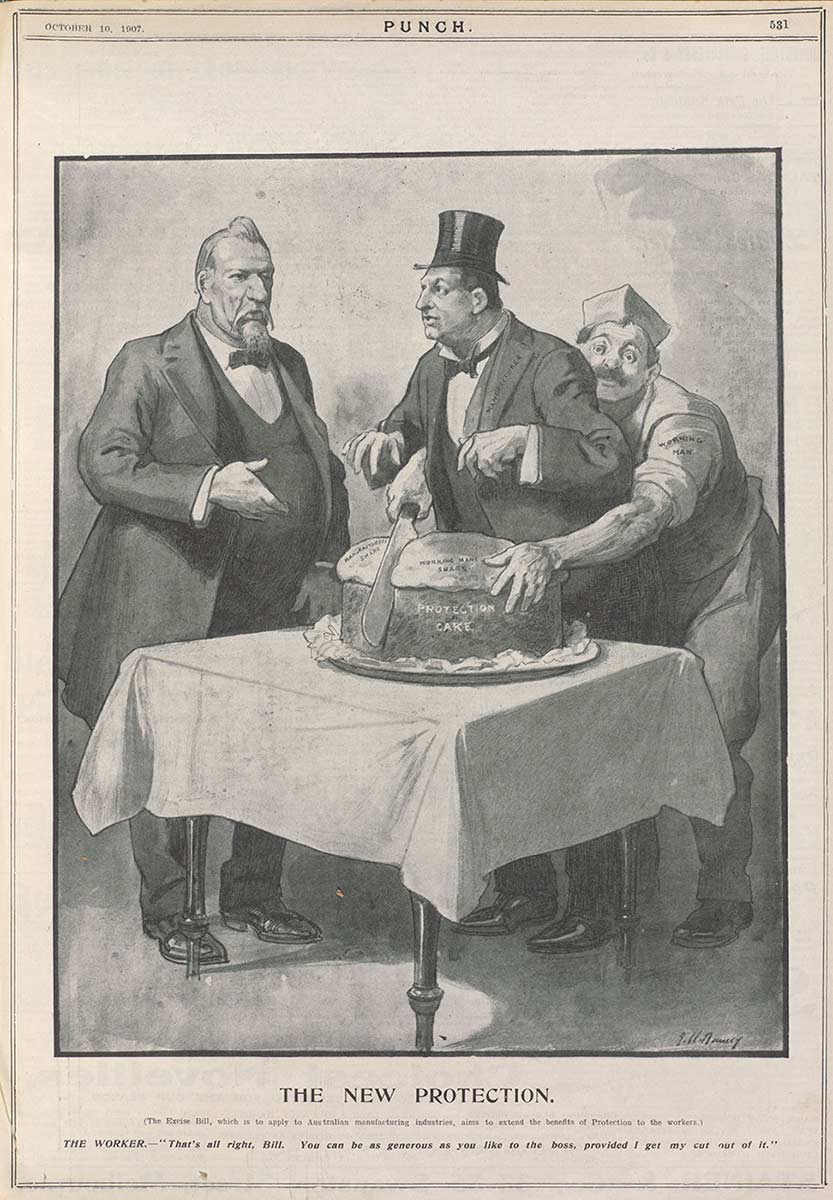

The AIMU’s ultimatum expressed its long-growing frustration with employers’ refusal to respect the official conciliation and arbitration system. In 1907 the federal government passed the Excise Tariff Act, requiring agricultural implement manufacturers to pay an additional tax on their products unless they paid a ‘fair and reasonable wage’.

A few months later, Justice HB Higgins of the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration ruled on the meaning of ‘fair and reasonable’, setting out a scale of minimum wages.

Employers like HV McKay refused to abide by Higgins’ ruling. In 1908 McKay challenged the Excise Tariff Act in the High Court, and the law was overturned. This allowed McKay to continue paying wages well below Higgins’ standard.

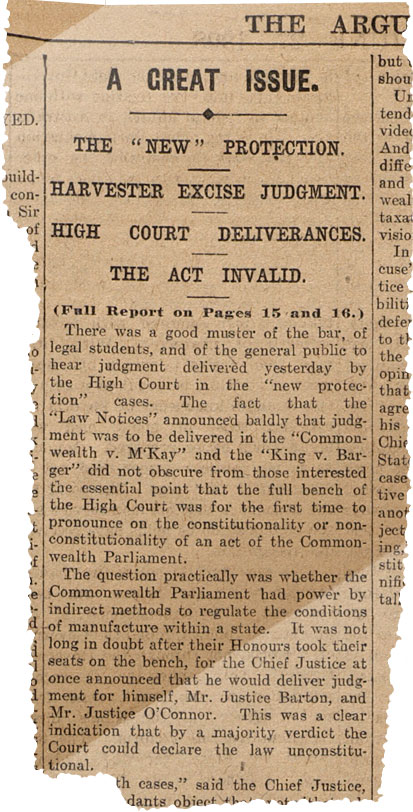

Excerpt from the Melbourne Argus, 27 June 1908

Transcript

A GREAT ISSUE.

THE "NEW" PROTECTION.

HARVESTER EXCISE JUDGMENT.

HIGH COURT DELIVERANCES. THE ACT INVALID.

(full report on pages 15 and 16.)

There was a good muster of the bar, of legal students, and of the general public to hear judgment delivered yesterday by the High Court in the "new protection" cases. The fact that the "law notices" announced baldly that judgment was to be delivered in the "Commonwealth v. M'Kay" and the "King v. Barger" did not obscure from those interested the essential point that the full bench of the High Court was for the first time to pronounce on the constitutionality or non‑constitutionality of an act of the Commonwealth parliament.

The question practically was whether the Commonwealth Parliament had power by indirect methods to regulate the conditions of manufacture within a state. It was not long in doubt after their honours took their seats on the bench, for the Chief Justice at once announced that he would deliver judgment for himself, Mr. Justice Barton, and Mr. Justice O'Connor. This was a clear indication that by a majority verdict it could declare the law unconstitutional.

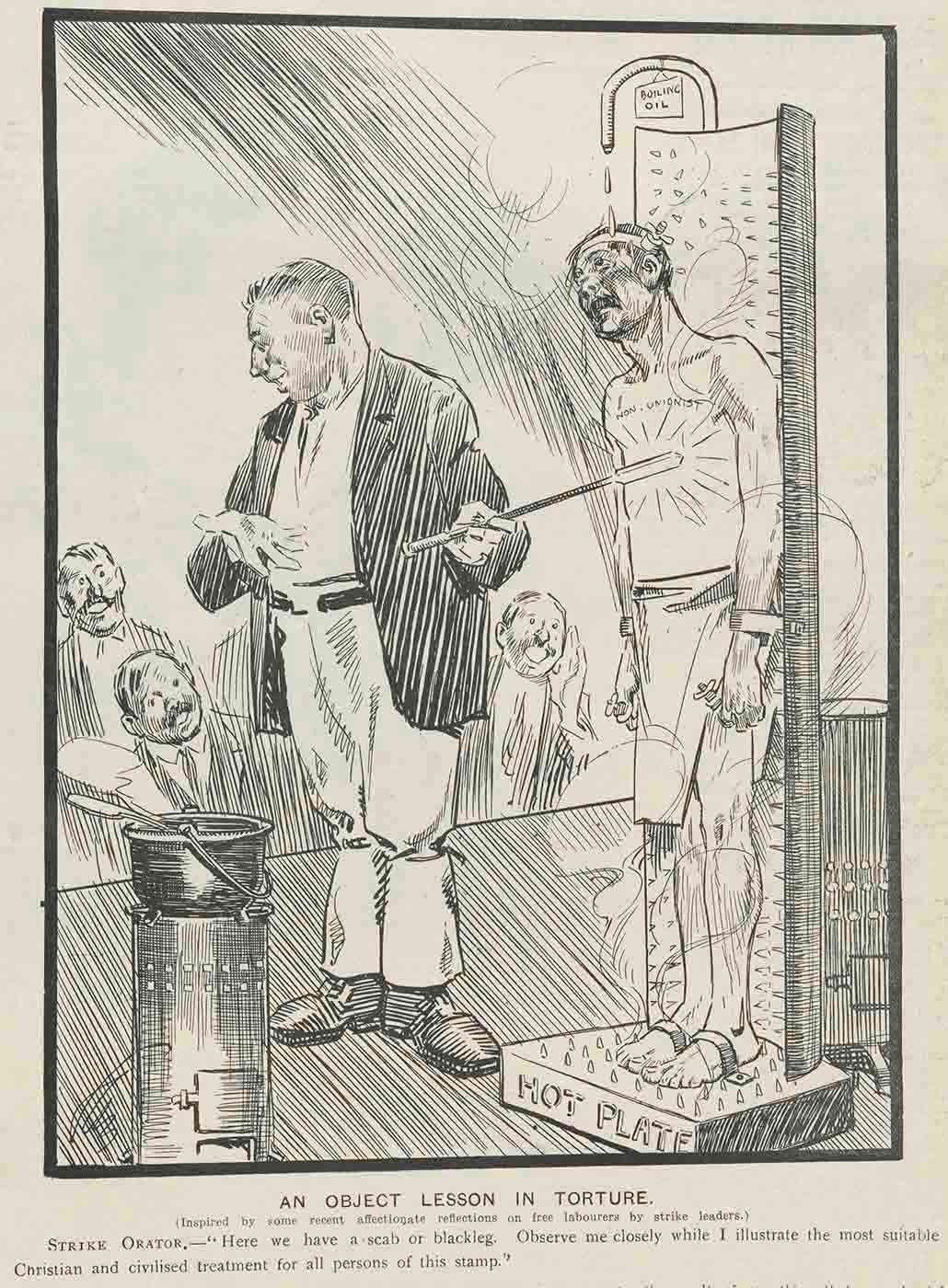

On the morning of 16 February agricultural implements workers at the Sunshine Harvester Works and at other factories in Melbourne went on strike. EF Russell, secretary of the Agricultural Implement Makers’ Union (AIMU), and HV McKay, the Sunshine works owner, addressed a crowd of workers outside the factory entrance.

Russell declared the union’s resolve to stop work until better pay and conditions were granted. McKay reiterated his position that he would not recognise union authority to control all labour at the factory.

Inside the works, many workshops stood almost deserted. In other areas, like the moulding department, where workers were not AIMU members, production continued as usual.

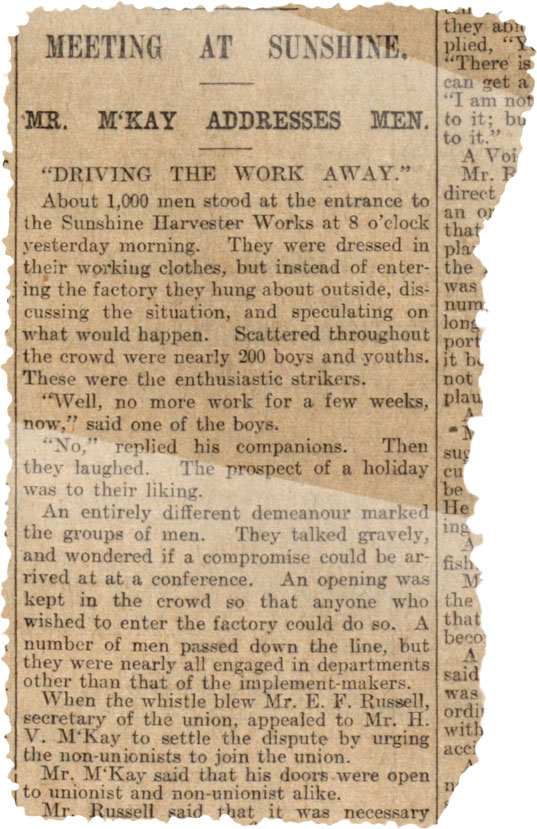

Excerpt from the Melbourne Argus, 17 February 1911

Transcript

MEETING AT SUNSHINE.

MR. M'KAY ADDRESSES MEN.

"DRIVING THE WORK AWAY."

About 1,000 men stood at the entrance to the Sunshine Harvester Works at 8 o'clock yesterday morning. They were dressed in their working clothes, but instead of entering the factory they hung about outside, discussing the situation, and speculating on what would happen. Scattered throughout the crowd were nearly 200 boys and youths. These were the enthusiastic strikers.

"Well, no more work for a few weeks, now," said one of the boys.

"No," replied his companions. Then they laughed. The prospect of a holiday was to their liking.

An entirely different demeanour marked the groups of men. They talked gravely, and wondered if a compromise could be arrived at at a conference. An opening was kept in the crowd so that anyone who wished to enter the factory could do so. A number of men passed down the line, but they were nearly all engaged in departments other than that of the implement‑makers.

When the whistle blew Mr. E.F. Russell, secretary of the union, appealed to Mr. H.V. M'Kay to settle the dispute by urging the non‑unionists to join the union.

Mr. M'Kay said that his doors were open to unionist and non‑unionist alike.

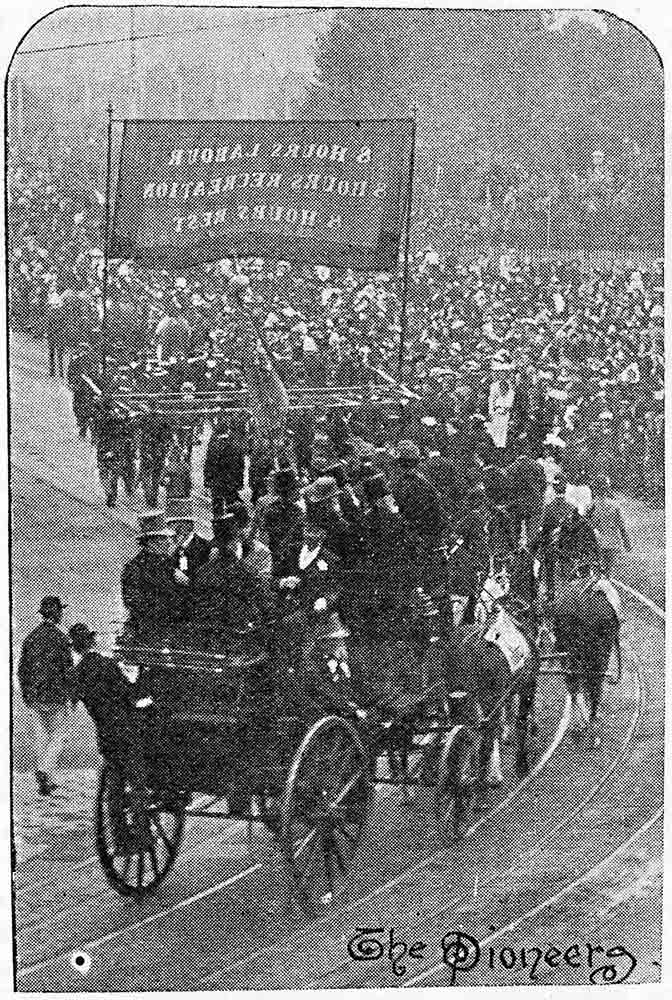

Union power

The trade union movement had emerged in Australia by the 1850s. In 1856 stonemasons employed to build Melbourne University marched to the Victorian Parliament calling for shorter working hours. In the middle of a gold-rush building boom, the government agreed and Victorian labourers employed on public works became the first in the world to get an eight-hour day without a cut in pay.

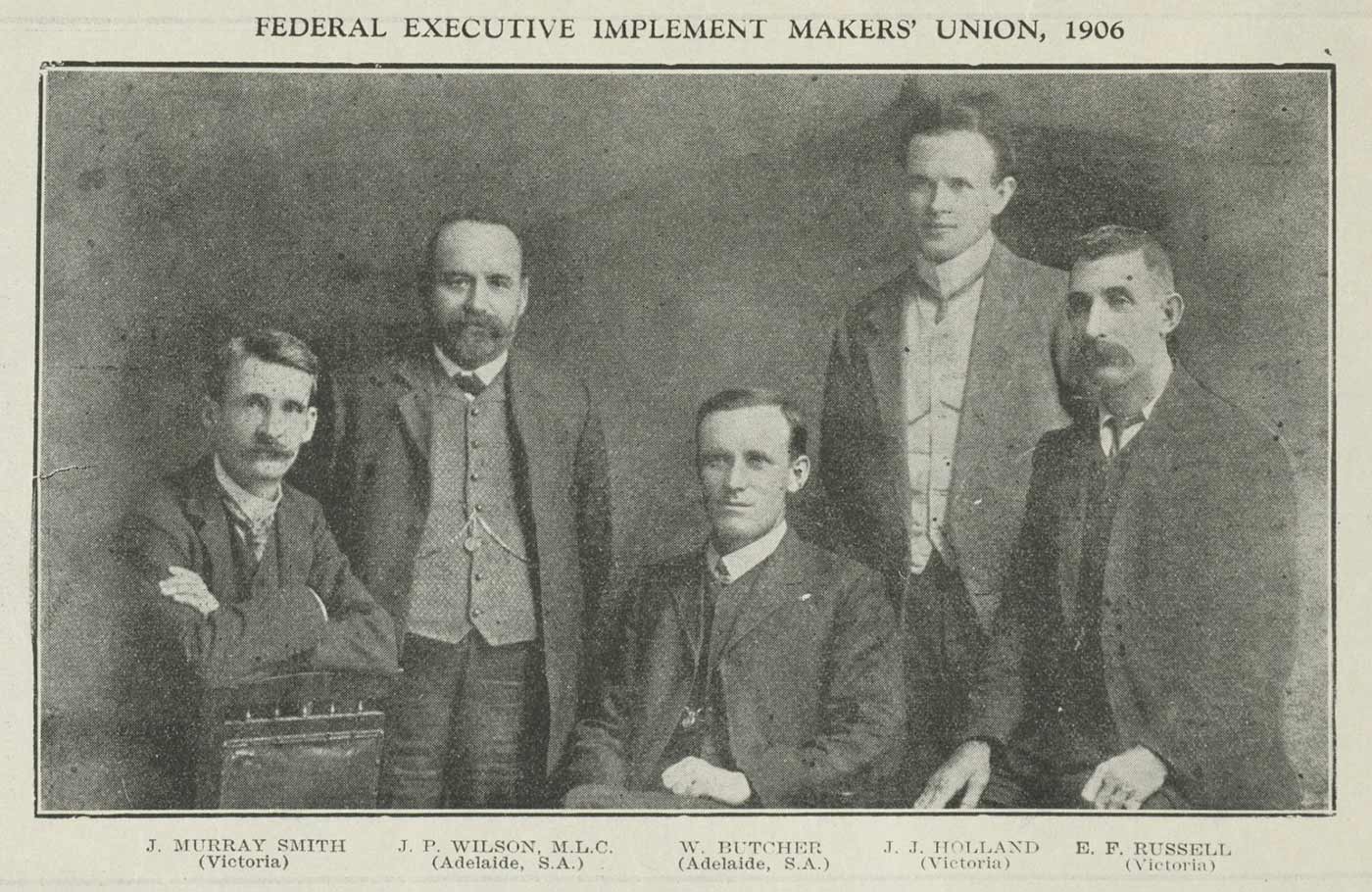

Unions were formed in many different industries in the following decades. The Agricultural Implement Makers’ Union (AIMU) was established in 1885 as agricultural production and its support industries expanded. The AIMU took a leading role in lobbying government on workers’ rights in the early 20th century.

On 17 February HV McKay, owner of the Sunshine Harvester Works, responded to the Agricultural Implement Makers’ Union (AIMU) call to strike by locking workers out of the factory. Nine other agricultural implement manufacturers joined McKay in a lockout.

Not all union members agreed with the strike action and the employers hoped that by preventing these men from working they would pressure the union to stop the strike. If the men couldn’t work, they didn’t get paid.

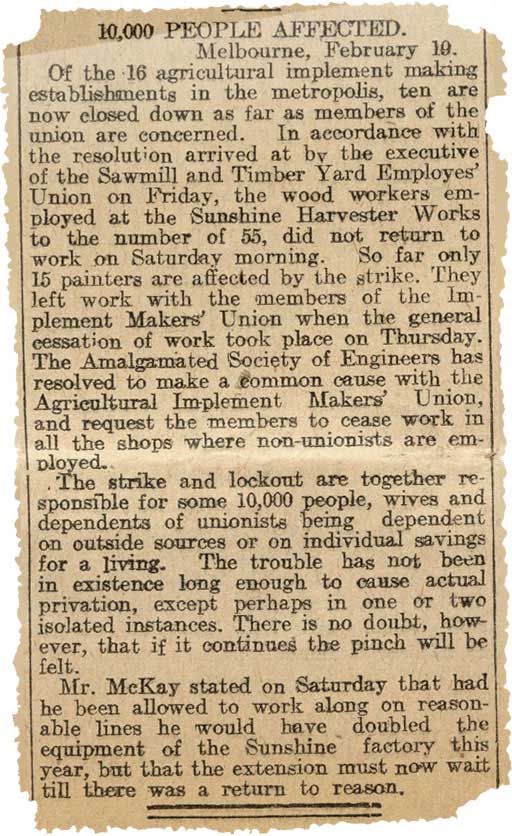

Excerpt from the Adelaide Advertiser, 20 February 1911

Transcript

10,000 PEOPLE AFFECTED.

Melbourne, February 19.

Of the 16 agricultural implement making establishments in the metropolis, ten are now closed down as far as members of the union are concerned. In accordance with the resolution arrived at by the executive of the Sawmill and Timber Yard employees' Union on Friday, the woodworkers employed at the Sunshine Harvester Works to the number of 55, did not return to work on Saturday morning. So far only 15 painters are affected by the strike. They left work with the members of the Implement Makers' Union when the general cessation of work took place on Thursday. The Amalgamated Society of Engineers has resolved to make a common cause with the Agricultural Implement Makers' Union, and request the members to cease work in all the shops where non‑unionists are employed.

The strike and lockout are together responsible for some 10,000 people, wives and dependents of unionists being dependent on outside sources or on individual savings for a living. The trouble has not been in existence long enough to cause actual privation, except perhaps in one or two isolated instances. There is no doubt, however, that if it continues the pinch will be felt.

Mr. McKay stated on Saturday that had he been allowed to work along on reasonable lines he would have doubled the equipment of the Sunshine factory this year, but that the extension must now wait till there was a return to reason.

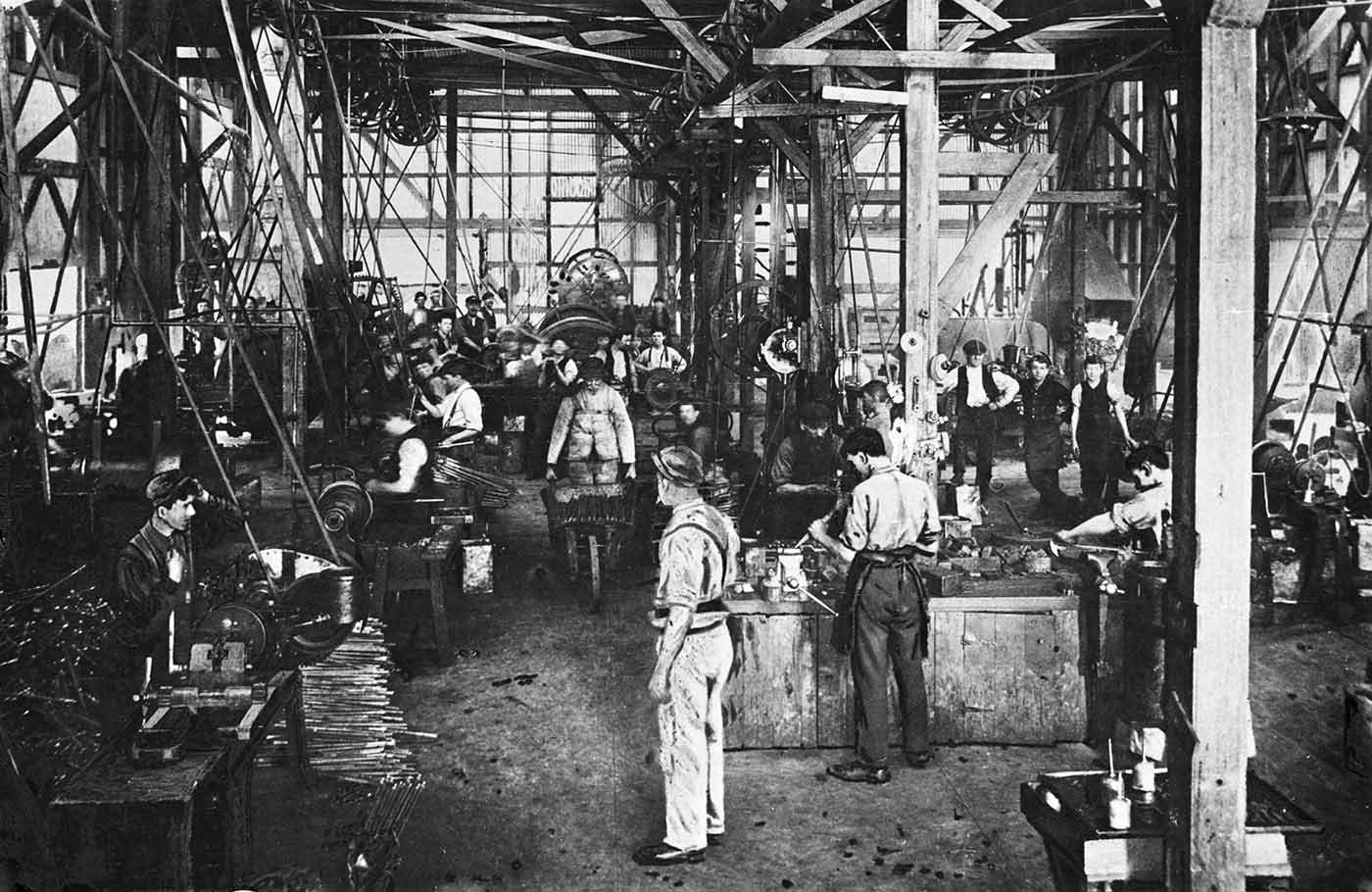

A booming enterprise

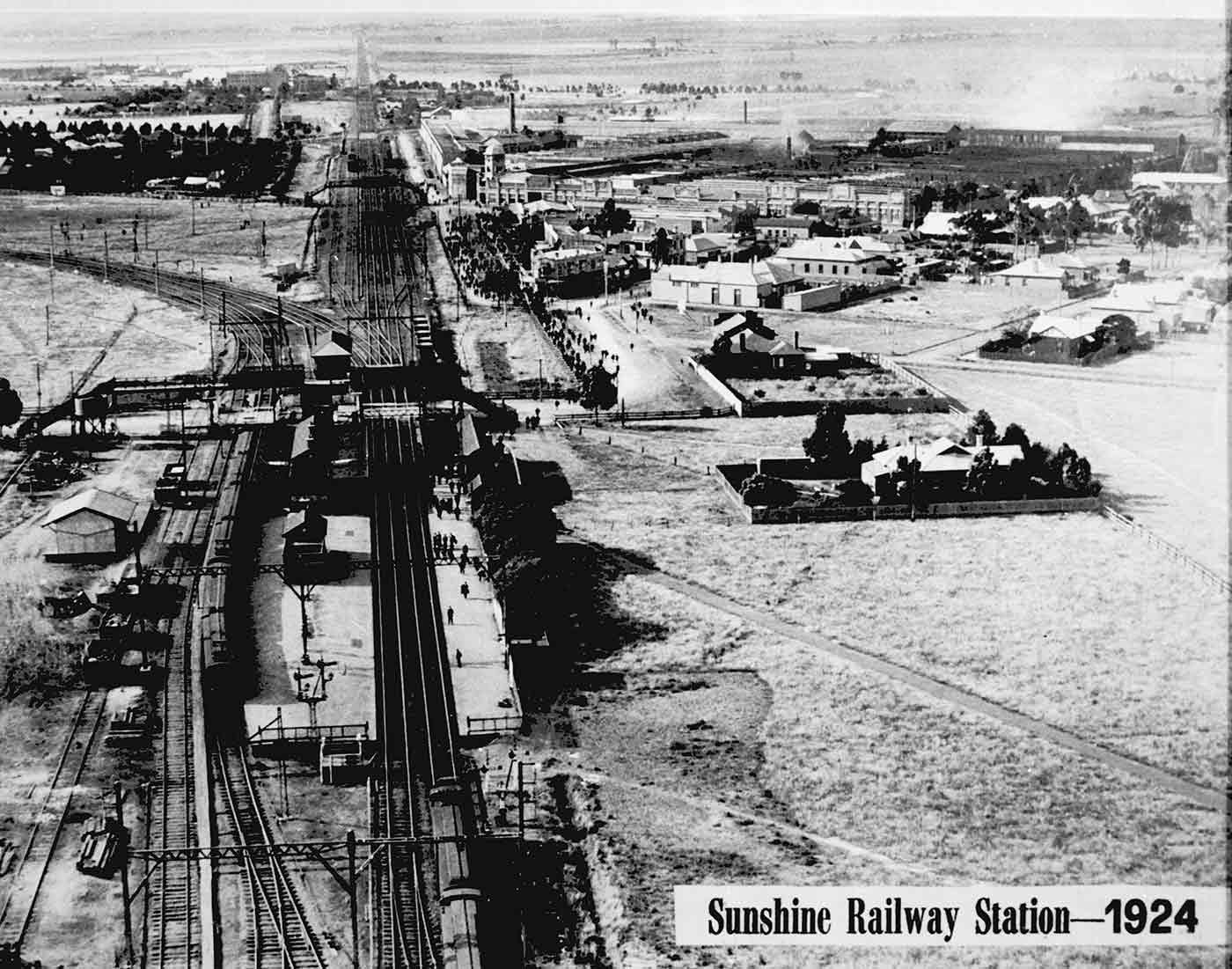

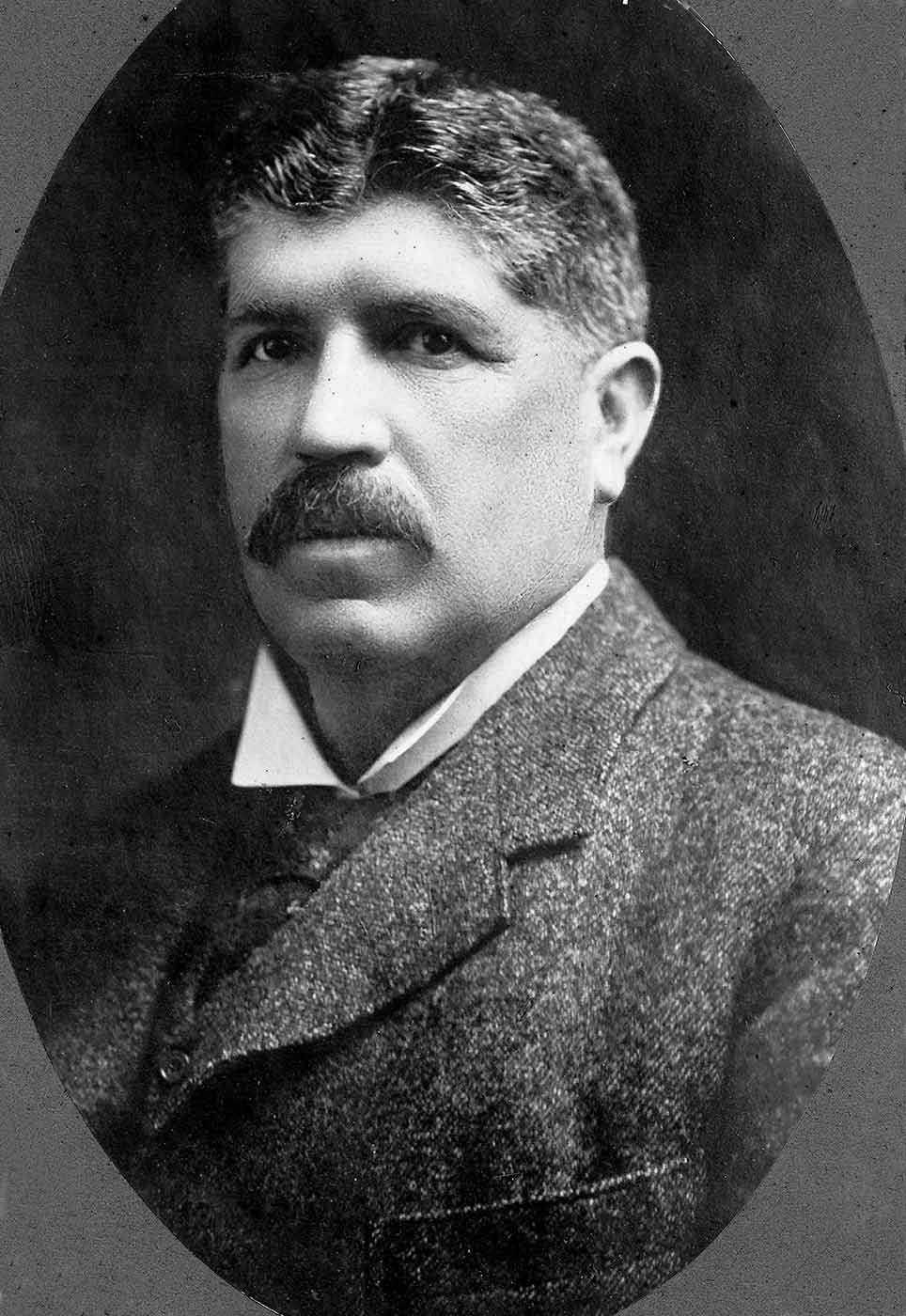

Farmer’s son HV McKay became one of several Australian entrepreneurs to develop a stripper harvester during the agricultural boom of the 1880s. McKay patented his first harvester in March 1885 and soon established an office and harvester factory in Ballarat, Victoria.

In 1892 his company was forced into liquidation by economic depression, but McKay refused to go under. He improved his harvester design and in 1894 launched the Sunshine Harvester Works and the Sunshine harvester.

In 1904 McKay purchased a failed implement factory at Braybrook Junction on the outskirts of Melbourne. The site offered room to expand his operations and railway lines to bring in supplies and send out products.

By 1907 McKay’s business was consolidated near Melbourne, and Braybrook Junction was renamed Sunshine.

20 February

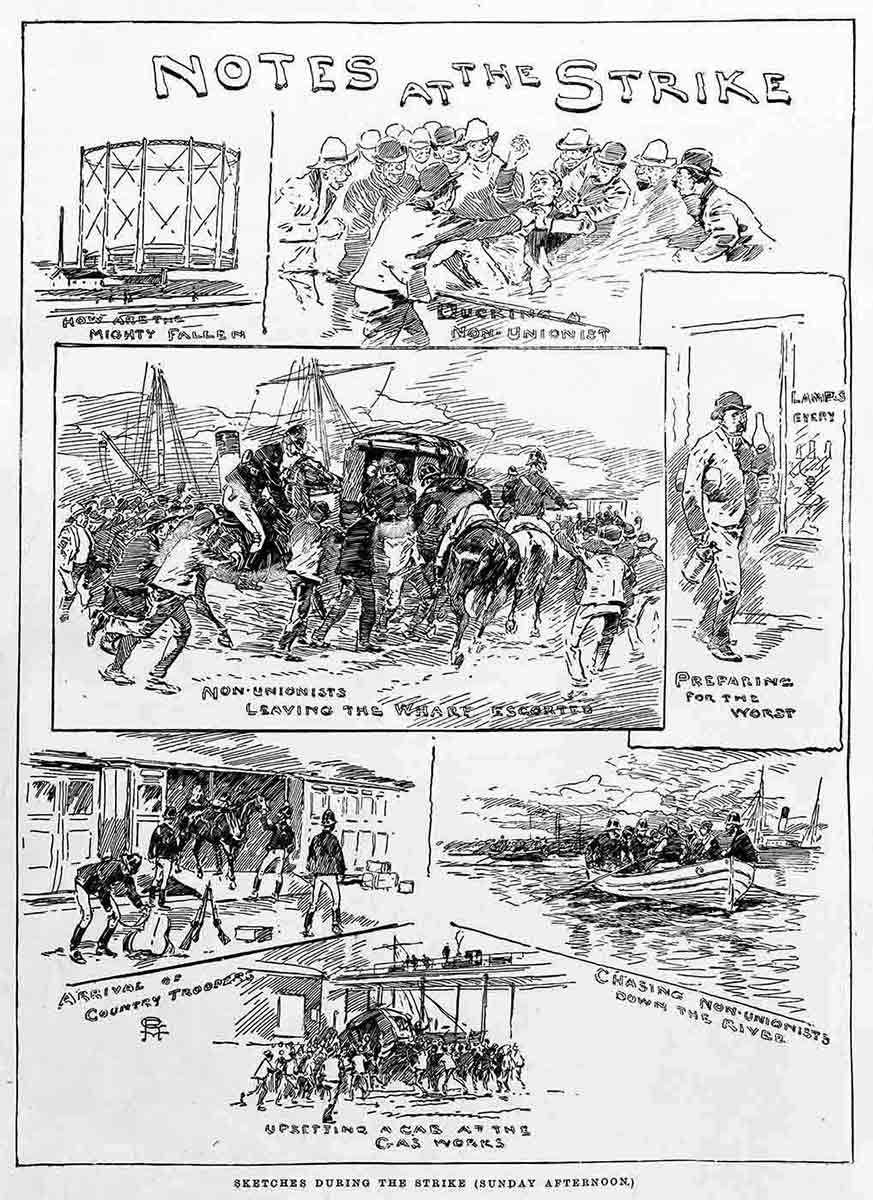

During the strike, Melbourne newspapers printed many different views about the union action and the employers’ response. The union and its members explained their reasons for striking. Non-unionists stated their opposition to the strike.

Housewives expressed concern for how they would pay their rent or mortgage, and farmers asked whether they would receive machinery they had ordered in time for the next harvest.

HV McKay, owner of the Sunshine Harvester Works, was often quoted in the papers. He stated his conviction that workers should be able to choose whether or not to join the union.

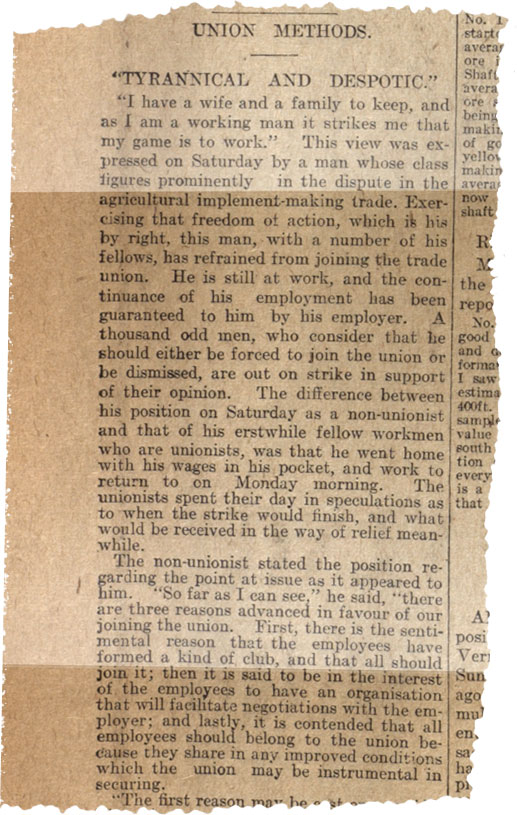

Excerpt from the Melbourne Argus, 20 February 1911

Transcript

UNION METHODS.

"TYRANNICAL AND DESPOTIC."

"I have a wife and a family to keep, and as I am a working man it strikes me that my game is to work." This view was expressed on Saturday by a man whose class figures prominently in the dispute in the agricultural implement‑making trade. Exercising that freedom of action, which is his by right, this man, with a number of his fellows, has refrained from joining the trade union. He is still at work, and the continuance of his employment has been guaranteed to him by his employer. A thousand‑odd men, who consider that he should either be forced to join the union or be dismissed, are out on strike in support of their opinion. The difference between his position on Saturday as a non‑unionist and that of his erstwhile fellow workmen who are unionists, was that he went home with his wages in his pocket, and work to return to on Monday morning. The unionists spent their day in speculations as to when the strike would finish, and what would be received in the way of relief meanwhile.

The non‑unionist stated the position regarding the point at issue as it appeared to him. "So far as I can see," he said, "there are three reasons advanced in favour of our joining the union. First, there is the sentimental reason that the employees have formed a kind of club, and that all should join it; then it is said to be in the interest of the employees to have an organisation that will facilitate negotiations with the employer; and lastly, it is contended that all employees should belong to the union because they share in any improved conditions which the union may be instrumental in securing ..."

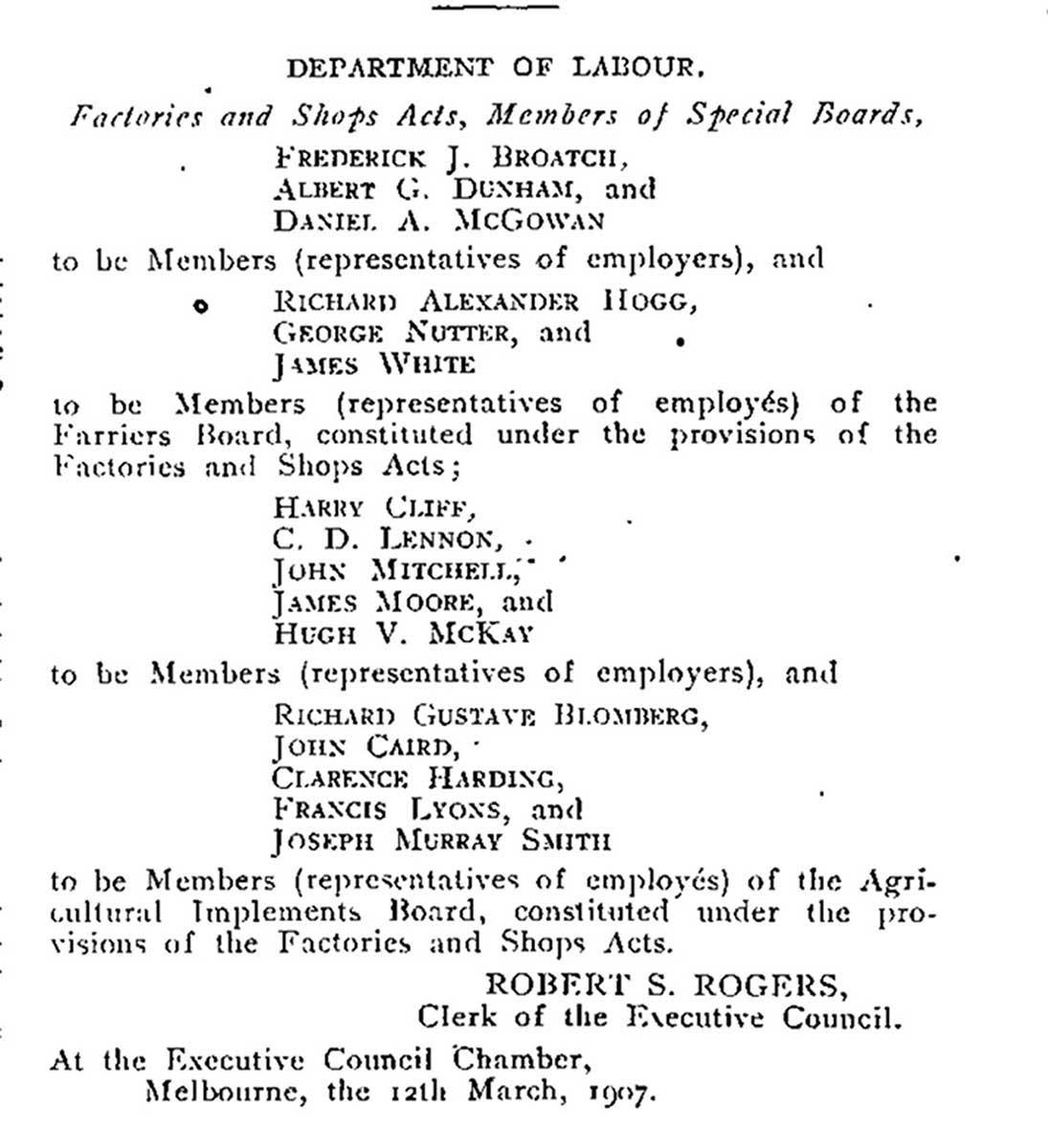

Negotiating wages

HV McKay strongly resisted government interference in how he paid his workers at the Sunshine Harvester Works. He believed individual workers should negotiate wages with their employers.

In 1904 McKay moved his business from Ballarat to Braybrook Junction, in part to escape the jurisdiction of the Wages Board system.

The Victorian Government established the first Wages Board in 1896 to regulate conditions in particular industries. In 1907 a board was established for the agricultural implements industry.

It delivered its first wage determinations in 1909, setting the minimum wage for unskilled labourers at 3 shillings less than that proposed in 1907 by Justice Higgins.

Factories and Shops Acts, Members of Special Boards (including the Agricultural Implements Board), 1907

Transcript

DEPARTMENT OF LABOUR.

Factories and Shops Acts, Members of Special Boards,

Frederick J. Broatch,

Albert G. Dunham, and

Daniel A. McGowanto be Members (representatives of employers), and

Richard Alexander Hogg

George Nutter, and

James Whiteto be Members (representatives of employees) of the Farriers Board, constituted under the provisions of the Factories and Shops Acts;

Harry Cliff,

C.D. Lennon,

John Mitchell,

James Moore, and

Hugh V. McKayto be Members (representatives of employers), and

Richard Gustave Blomberg

John Caird,

Clarence Harding,

Francis Lyons, and

Joseph Murray Smithto be Members (representatives of employees) of the Agricultural Implements Board, constituted under the provisions of the Factories and Shops Acts.

ROBERT S. ROGERS,

Clerk of the Executive Council.At the Executive Council Chamber,

Melbourne, the 12th March, 1907.

On 22 February Victorian Premier John Murray offered to hold a conference between representatives of the Agricultural Implement Makers’ Union (AIMU) and employers.

Murray had no legal power to force a resolution to the strike but was anxious to end the dispute to prevent further losses in production and wages.

Murray’s proposed conference never eventuated but his actions helped persuade Prime Minister Andrew Fisher to intervene.

Excerpt from the Melbourne Argus, 22 February 1911

Transcript

HARVESTER STRIKE.

PREMIER INTERVENES.

CONFERENCE THIS MORNING.

MOVEMENTS OF WORKMEN.

The Premier (Mr. Murray) proposes to take steps with the object of summoning an informal conference this morning of representatives of employers and employees in the agricultural implement trade, in the hope of securing a settlement of the existing trouble. Mr. Murray is not invested with any legal powers, and in moving in the matter he is actuated by the desire to prevent any further loss to either side by a continuance of the strike.

Among the members of the Agricultural Implement Employees' Union and leaders of other labour organisations, the question of endeavouring to have matters adjusted by a conference was freely discussed yesterday. While the employers have already refused to meet representatives of the union, holding that there was nothing to confer about, it is considered that the position has materially changed by the progress made and the nature of the determination arrived at at the meeting of the wages board on Monday night. It is argued that, while the men struck against working with non-unionists, this action was the outcome of feeling engendered by the delay of the wages board in dealing with the claims that were submitted to it on behalf of the employees.

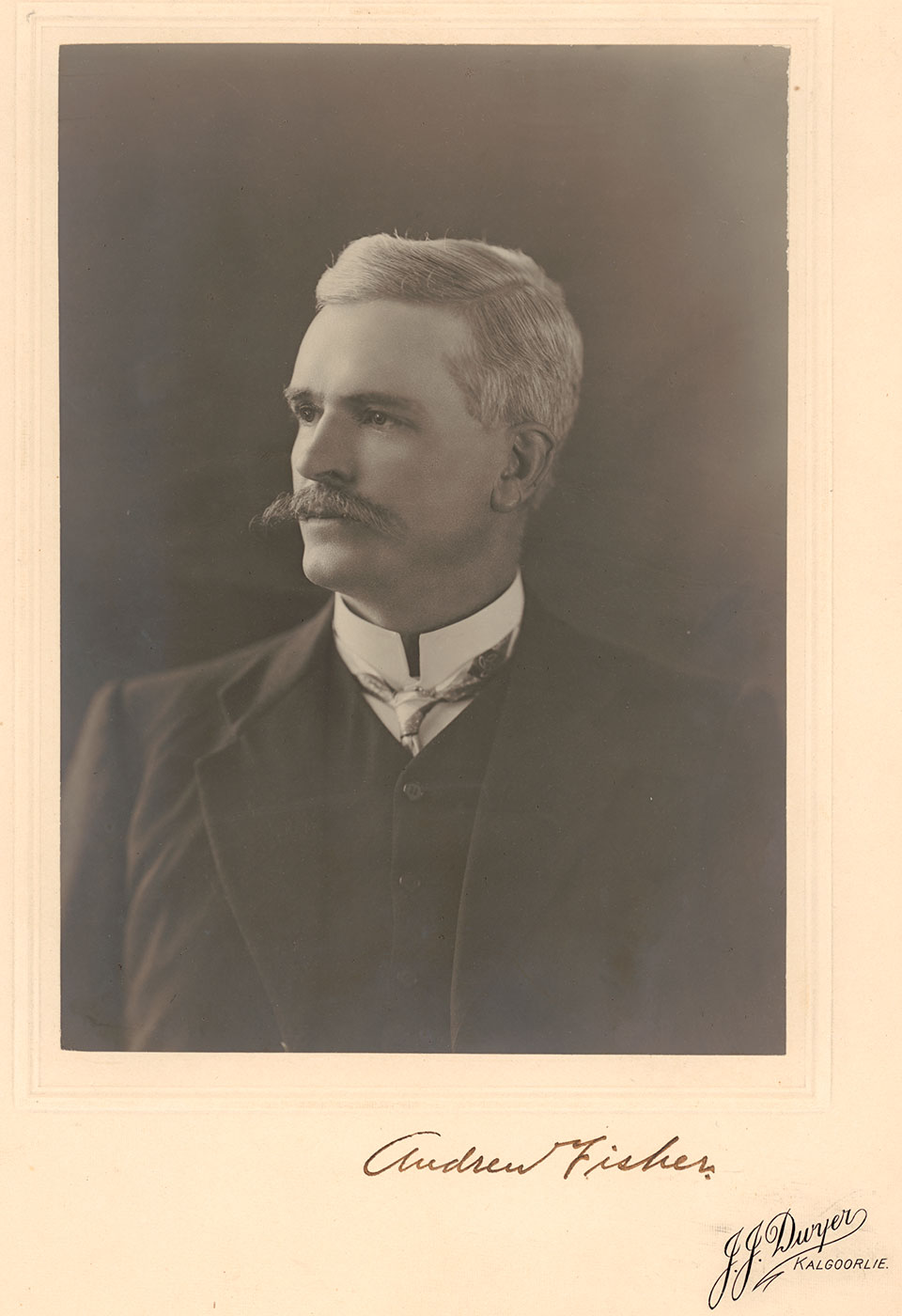

On February 24 Prime Minister Andrew Fisher joined attempts to end the strike. He met first with HV McKay, owner of the Sunshine Harvester Works, to hear the employers’ position and propose a conference bringing employers and union together to negotiate a resolution.

McKay took Fisher’s suggestion to the other employers, who agreed to thank Fisher for his efforts but saw no use in a conference. They also refused to consider the union’s core demand, that they employ only unionised labour.

Fisher then met with representatives of the union, who also refused to give way on their demand for a fully unionised workforce. The proposal for a conference was shelved.

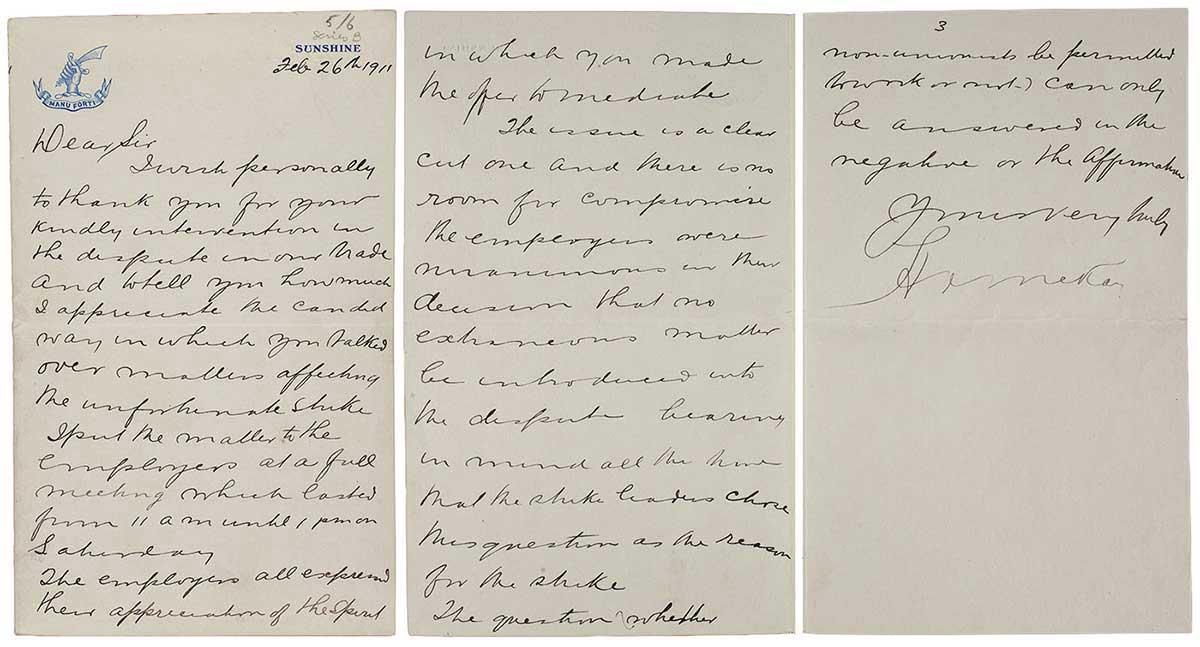

Letter from HV McKay to Prime Minister Andrew Fisher, dated 26 February 1911

Transcript

Dear Sir

I wish personally to thank you for your kindly intervention in the dispute in our trade and to tell you how much I appreciate the candid way in which you talked over matters affecting the unfortunate strike.

I put the matter to the employers at a full meeting which lasted from 11 am until 1 pm on Saturday. The employers all expressed their appreciation of the spirit in which you made the offer to mediate. The issue is a clear cut one and there is no room for compromise.

The employers arose unanimous in their decision that no extraneous matter be introduced into the dispute bearing in mind all the time that the strike leaders chose this question as the reason for the strike.

The question (whether Non-unionists be permitted to work or not) can only be answered in the negative or the affirmative.

Yours very humbly

HV McKay

Word went around among the strikers that a meeting was being called at the Sunshine tennis court. The union executive, which had not authorised the meeting, branded the organisers disloyal. It encouraged its members to go to Sunshine in force to discover the identity of the ‘traitors’ and to show employers that they would stand firm to their principles.

On the morning of 1 March over 300 strikers met at Sunshine for the meeting. At the train station, a group of 50–60 people encouraged strikers alighting from the train to stay away from the tennis court. Union president J Skehan addressed the crowd at the meeting and identified the organiser as a disaffected striker, labelling his actions as contrary to the union’s cause.

Excerpt from the Footscray Advertiser, 4 March 1911

Transcript

An announcement that a meeting open only to unionists above 21 years of age, at which neither employers nor trade representatives were to be admitted was to be held at the Sunshine Tennis Court under the auspices of the Sunshine Union Committee on Wednesday morning caused some stir in Trades Hall circles. No such meeting had been authorised by the executive and it was felt that an attempt was being made to unduly force the hands of that body by the taking of a vote adverse to the strike. The promoters, at the Trades Hall meeting on Tuesday, were promptly branded as traitors, and it was decided to attend the meeting in force on Wednesday morning to see who was responsible, the suspicion being entertained that the employers themselves in an effort to cause a split in the ranks, had a voice in the matter.

In consequence the 10 33 a.m., train from Melbourne to Sunshine on the day named was filled by fully three hundred strikers, amongst the number a large proportion of Footscrayites. On arrival at Sunshine there was a crowd of fifty or sixty persons waiting and the cry "Unionists this way" attracted the arrivals to a spot on the south side of the Sunshine station and a good distance from the tennis court. A placard was also displayed bearing the words:—

"Beware of the Tennis Court fake. It is not a union meeting.—No unionist need apply."

By March unions across Australia were pledging support for the Agricultural Implement Makers’ Union (AIMU) strike. Sympathisers sent in donations to help with strike pay, and unionised workers in other agricultural implements businesses discussed how they could support the Melbourne strikers.

On Saturday 11 March workers at May Brothers, an agricultural implements factory in Gawler, South Australia, went out on strike in support of the AIMU. Unions in other industries soon followed.

Once the strike had spread across state lines, it came under the jurisdiction of the Commonwealth Government. The Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration was now legally entitled to intervene to settle the dispute.

Article from the Adelaide Advertiser, 11 March 1911

Transcript

IMPLEMENT TRADE STRIKE.

EXTENSION TO GAWLER.

The secretary of the South Australian branch of the Agricultural Implement Workers' Federation (M. A.F. Block), and the secretary of the Engine Drivers' and Firemen's Association (Mr. W.S. Hamilton) travelled to Gawler by the express on Friday in order to attend a meeting of the Gawler implement makers. For some weeks a movement has been on foot among the men at Gawler in the direction of objecting to work with non‑unionists. A great number of those who have been holding aloof from the union have joined during the last week, and it was hoped that they would all have been enrolled by Friday night. In the event of men still refusing to join a strike was threatened. It is anticipated that the Victorian and South Australian implement workers' strikes will constitute an inter-State dispute, and lead to intervention by Mr. Justice Higgins. Consequently there now appears to be a prospect of the two industrial troubles being settled by the Federal Arbitration Court.

On 13 March some Melbourne agricultural implement factories resumed work with reduced staff numbers. At the Sunshine Harvester Works, owner HV McKay sourced free (non-union) labour from all over Australia and called on his office staff to assist on the factory floor, undertaking tasks like unloading coal.

As the strike wore on, a number of unionists also returned to work. Many unionised workers were dedicated to the Agricultural Implement Makers’ Union’s objective, but some had stopped work to avoid being harassed by fellow unionists. Unionists who went back to work before the strike had ended were labelled blacklegs or scabs. Even after the strike had ended, these names remained.

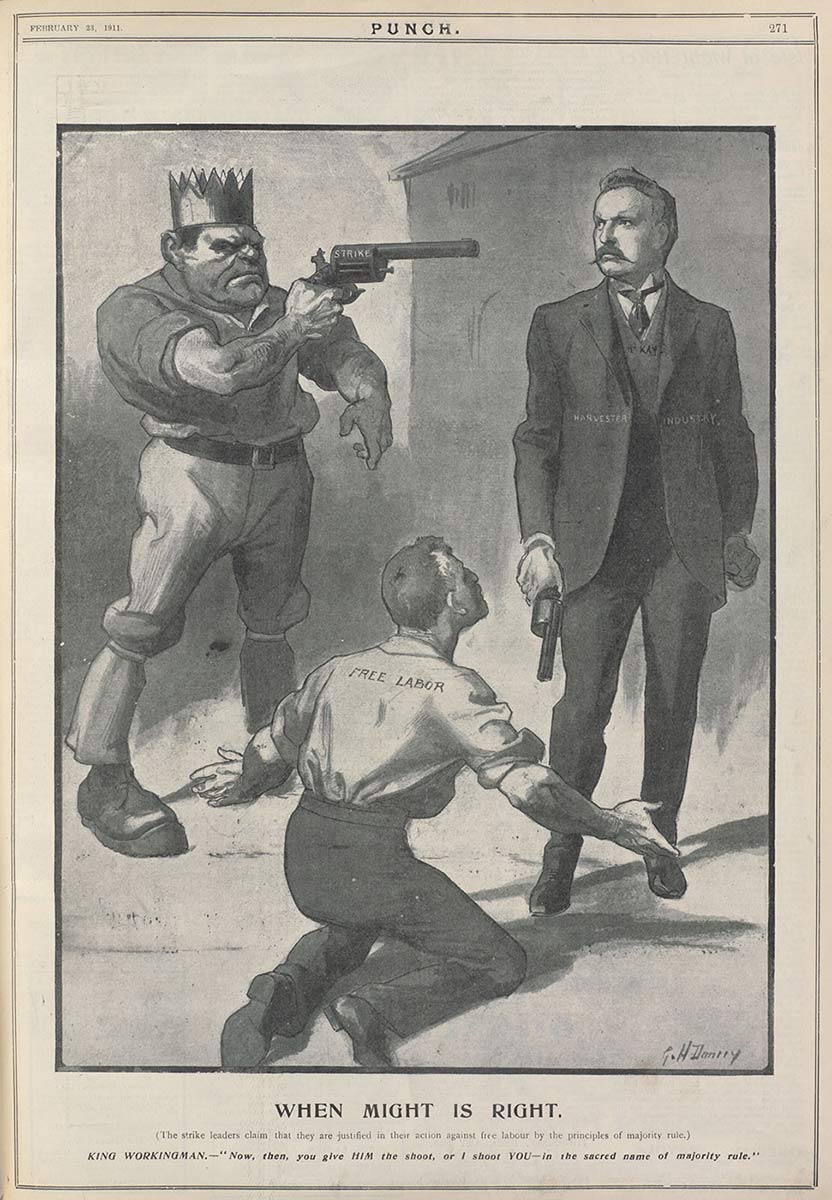

Melbourne Punch, 27 April 1907

Text below image

AN OBJECT LESSON IN TORTURE.

(Inspired by some recent affectionate reflections on free labourers by strike leaders.)STRIKE ORATOR:— "Here we have a scab or blackleg. Observe me closely while I illustrate the most suitable Christian and civilised treatment for all persons of this stamp."

On 20 March Justice HB Higgins, President of the Commonwealth Court of Arbitration and Conciliation, called a conference in an attempt to end the Agricultural Implement Makers’ Union (AIMU) strike. Now that the strike had spread beyond Victoria, Higgins was legally entitled to compel representatives from all parties involved in the dispute to negotiate.

At the conference, the AIMU dropped its demand that employers use only non-union labour, and employers agreed to raise wage rates to those set by Higgins in his 1907 ruling. However, employers refused to accede to the AIMU’s demand that they officially recognise the place of shop stewards, who represented the union, on the factory floor.

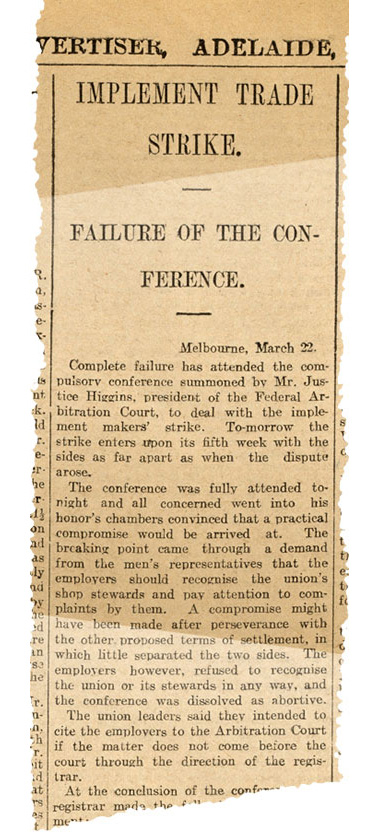

Excerpt from the Adelaide Advertiser, 23 March 1911

Transcript

IMPLEMENT TRADE STRIKE.

FAILURE OF THE CONFERENCE.

Melbourne, March 22.

Complete failure has attended the compulsory conference summoned by Mr. Justice Higgins, president of the Federal Arbitration Court, to deal with the implement makers' strike. To-morrow the strike enters upon its fifth week with the sides as far apart as when the dispute arose.

The conference was fully attended tonight and all concerned went into his honour's chambers convinced that a practical compromise would be arrived at. The breaking paint came through a demand from the men's representatives that the employers should recognise the union's shop stewards and pay attention to complaints by them. A compromise might have been made after perseverance with the other proposed terms of settlement, in which little separated the two sides. The employers however, refused to recognise the union or its stewards in any way, and the conference was dissolved as abortive.

The union leaders said they intended to cite the employers to the Arbitration Court if the matter does not come before the court through the direction of the registrar.

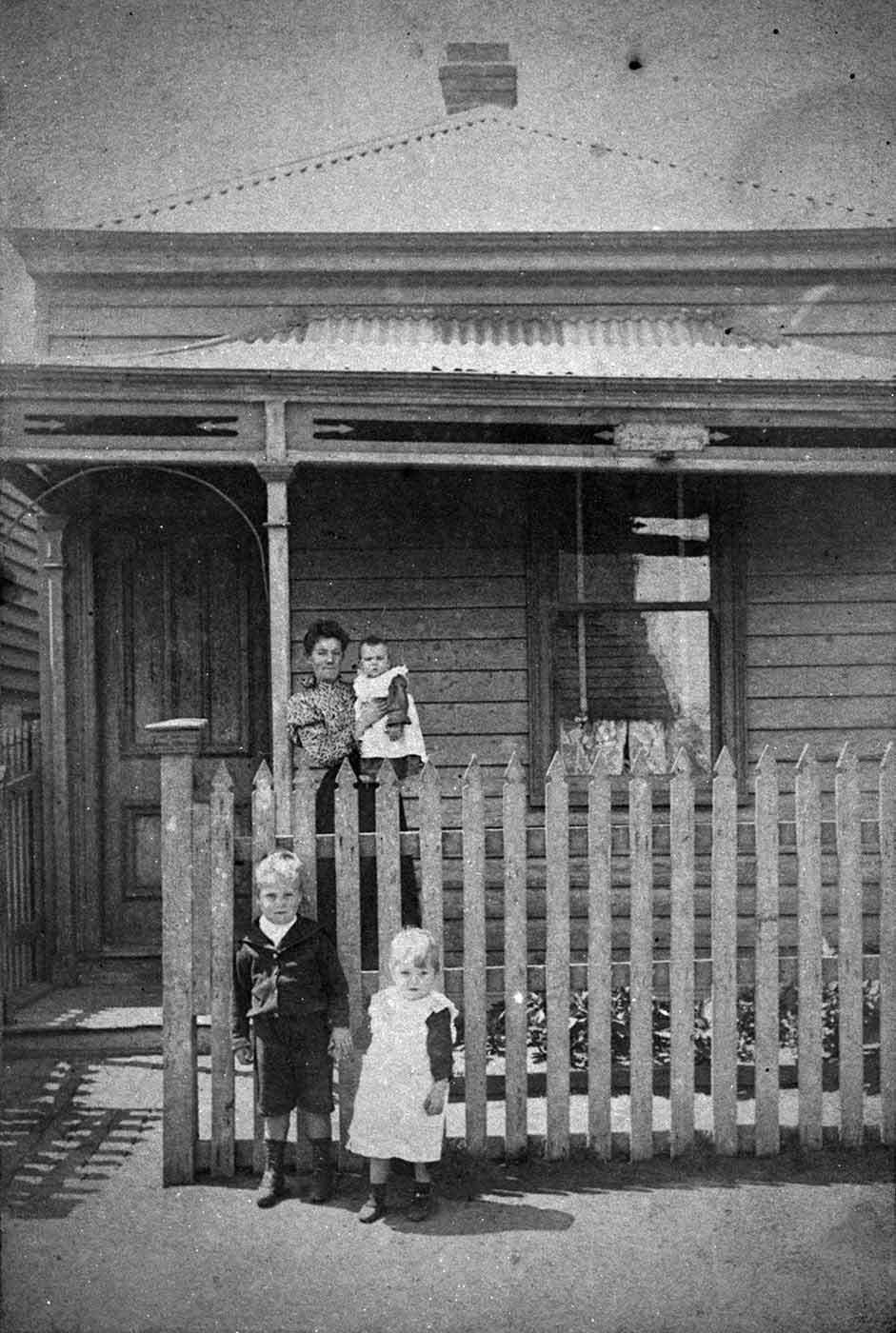

The Agricultural Implement Makers’ Union (AIMU) strike had a significant impact on workers’ families. An estimated 10,000 people from across Melbourne were without their usual means of support. Suburbs like Sunshine and Footscray, near the Sunshine Harvester Works, were hit particularly hard.

The AIMU supported the strike by awarding strike pay to its members. During the first few weeks of the action, married men received £1 a week, while single men received 10s. This was later increased to £1 10s for married men and £1 for single men.

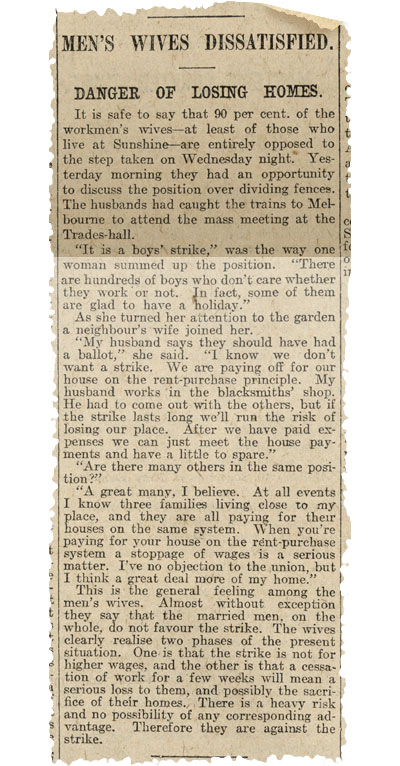

Excerpt from the Melbourne Argus, 17 February 1911

Transcript

MEN'S WIVES DISSATISFIED.

DANGER OF LOSING HOMES.

It is safe to say that 90 per cent. of the workmen's wives—at least of those who live at sunshine—are entirely opposed to the step taken on Wednesday night. Yesterday morning they had an opportunity to discuss the position over dividing fences. The husbands had caught the trains to Melbourne to attend the mass meeting at the Trades-hall.

"It is a boys' strike," was the way one woman summed up the position. "There are hundreds of boys who don't care whether they work or not. In fact, some of them are glad to have a holiday."

As she turned her attention to the garden a neighbour's wife joined her.

"My husband says they should have had a ballot," she said. "I know we don't want a strike. We are paying off for our house on the rent‑purchase principle. My husband works in the blacksmiths' shop. He had to come out with the others, but if the strike lasts long we'll run the risk of losing our place. After we have paid expenses we can just meet the house payments and have a little to spare."

"Are there many others in the same position?"

"A great many, I believe. At all events I know three families living close to my place, and they are all paying for their houses on the same system. When you're paying for your house on the rent‑purchase system a stoppage of wages is a serious matter. I've no objection to the union, but I think a great deal more of my home."

This is the general feeling among the men's wives. Almost without exception they say that the married men, on the whole, do not favour the strike. The wives clearly realise two phases of the present situation. One is that the strike is not for higher wages, and the other is that cessation of work for a few weeks will mean a serious loss to them, and possibly the sacrifice of their homes. There is a heavy risk and no possibility of any corresponding advantage. Therefore they are against the strike.

The cost of living

During the strike, the AIMU based its rate of strike pay in part on the minimum wage established by Justice Higgins in his 1907 ruling. Higgins ruled that an unskilled labourer should receive a minimum weekly pay of £1 12s 5d (equivalent to about $190 today), judging that this would provide for rent, groceries, bread, meat, milk, fuel, vegetables and fruit for a family of five.

Until 1907 wages were generally determined by employers. Higgins based his ruling on evidence from workers and housewives on what it cost them to live. Higgins’ judgement was overturned by the High Court in 1908, but his ‘living wage’ method became a principle of Australian law.

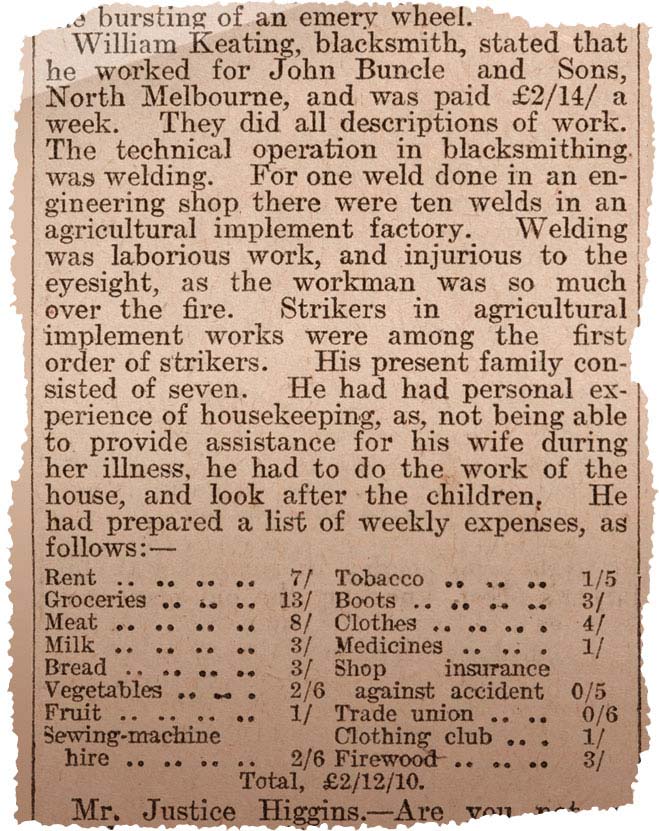

Excerpt from the Melbourne Argus, 25 October 1907

Transcript

William Keating, blacksmith, stated that he worked for John Buncle and Sons, North Melbourne, and was paid £2/14/ a week. They did all descriptions of work. The technical operation in blacksmithing was welding. For one weld done in an engineering shop there were ten welds in an agricultural implement factory. Welding was laborious work, and injurious to the eye‑sight, as the workman was so much over the fire. Strikers in agricultural implement works were among the first order of strikers. His present family consisted of seven. He had had personal experience of housekeeping, as, not being able to provide assistance for his wife during her illness, he had to do the work of the house, and look after the children. He had prepared a list of weekly expenses, as follows:—

Rent 7/; Groceries, 13/; Meat, 8/; Milk, 3/; Bread, 3/; Vegetables 2/6; Fruit, 1/; Sewing-machine hire, 2/6; Tobacco, 1/5; Boots, 3/; Clothes, 4/; Medicines 1/; Shop insurance against accident 0/5; Trade union, 0/6; Clothing club, 1/; Firewood, 3/.

Total, £2/12/10.

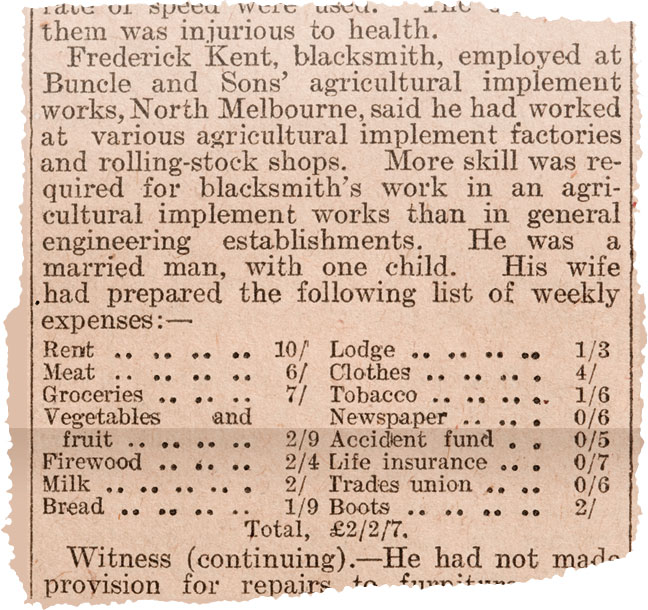

Excerpt from the Melbourne Argus, 25 October 1907

Transcript

Frederick Kent, blacksmith, employed at Buncle and Sons' agricultural implement works, North Melbourne, said he had worked at various agricultural implement factories and rolling‑stock shops. More skill was required for blacksmith's work in an agricultural implement works than in general engineering establishments. He was a married man, with one child. His wife had prepared the following list of weekly expenses:—

Rent, 10/; Meat, 6/; Groceries, 7/; Vegetables and fruit, 2/9; Firewood, 2/4; Milk, 2/; Bread, 1/9; Lodge, 1/3; Clothes, 4/; Tobacco, 1/6; Newspaper, 0/6; Accident fund, 0/5; Life insurance, 0/7; Trades union, 0/6; Boots, 2/.

Total, £2/2/7.

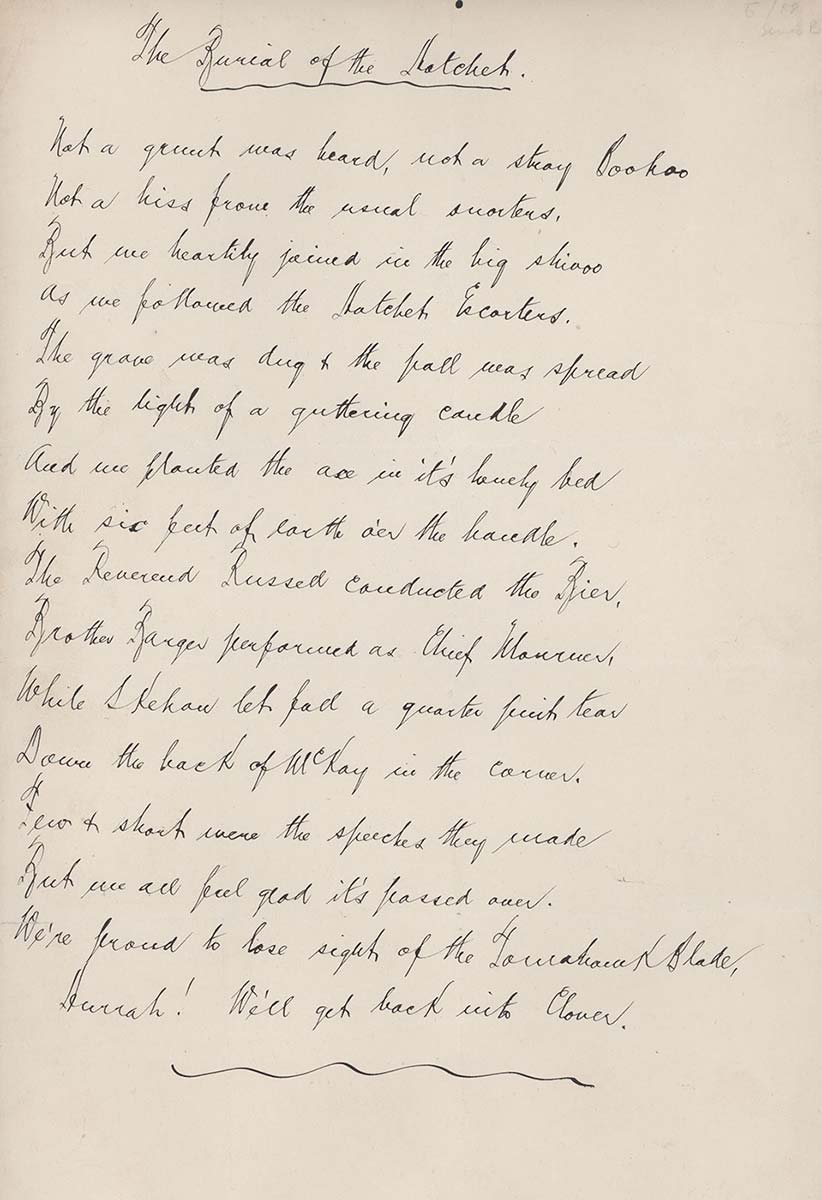

By the beginning of May the union’s resources were exhausted and employers were eager for a full workforce to complete orders for the coming season. The employers agreed to re-employ strikers and pay wages set by the Wages Board, and the union agreed to withdraw their demands that shop stewards be formally recognised and only unionist labour be employed in agricultural implements factories.

The strike officially ended on 16 May, three long months after it had started. Union organisers thought the strike would last only a few days. It cost an estimated £54,000 in lost wages and over £250,000 in lost production and sales, and left the AIMU bankrupt and incapable of pursuing any significant industrial action until 1925.

Transcript of poem by NB McKay

The Burial of the Hatchet

Not a grunt was heard, not a stray Boohoo

Not a hiss from the usual snorters,

But we heartily joined in the big shivoo

As we followed the Hatchet Escorters.

The grave was dug & the pall was spread

By the light of a guttering candle,

And we planted the axe in its lonely bed

With six feet of earth o’er the handle.

The Reverend Russell conducted the Bier,

Brother Barger performed as Chief Mourner,

While Skehan let fall a quarter pint tear

Down the back of McKay in the corner.

Few & short were the speeches they made

But we all feel glad it’s passed over.

We’re proud to lose sight of the Tomahawk Blade.

Hurrah! We’ll get back into Clover.

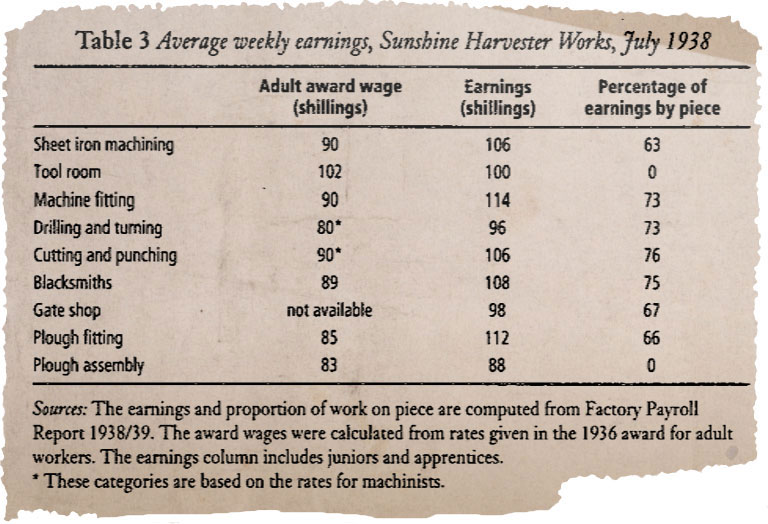

By August full production had resumed at the Sunshine Harvester Works. Owner HV McKay then moved to introduce piecework, paying workers according to what they produced rather than the hours they worked, pressuring them to work harder to earn the minimum wage.

Piecework and other changes to factory processes, as well as the union’s continued fight to improve wages, saw the Sunshine works remain the site of industrial disputes for decades.

McKay’s opinion of the unions never changed, but the 1911 strike encouraged him to seek his workers’ loyalty through schemes improving conditions and benefits. During the 1920s he introduced pensions and retirement allowances, a sick-pay scheme and a mortuary fund.

Table in text form

Table 3 Average weekly earnings, Sunshine Harvester Works, July 1938

Adult award wage

(shillings)Earnings

(shillings)Percentage of

earnings by pieceSheet iron machining 90 106 63 Tool room 102 100 0 Machine fitting 90 114 73 Drilling and turning 80* 96 73 Cutting and punching 90* 106 76 Blacksmiths 89 108 75 Gate shop not available 98 67 Plough fitting 85 112 66 Plough assembly 83 88 0

Sources: The earnings and proportion of work on piece are computed from Factory Payroll Report 1938/39. The award wages were calculated from rates given in the 1936 award for adult workers. The earnings column includes juniors and apprentices.*These categories are based on the rates for machinists.

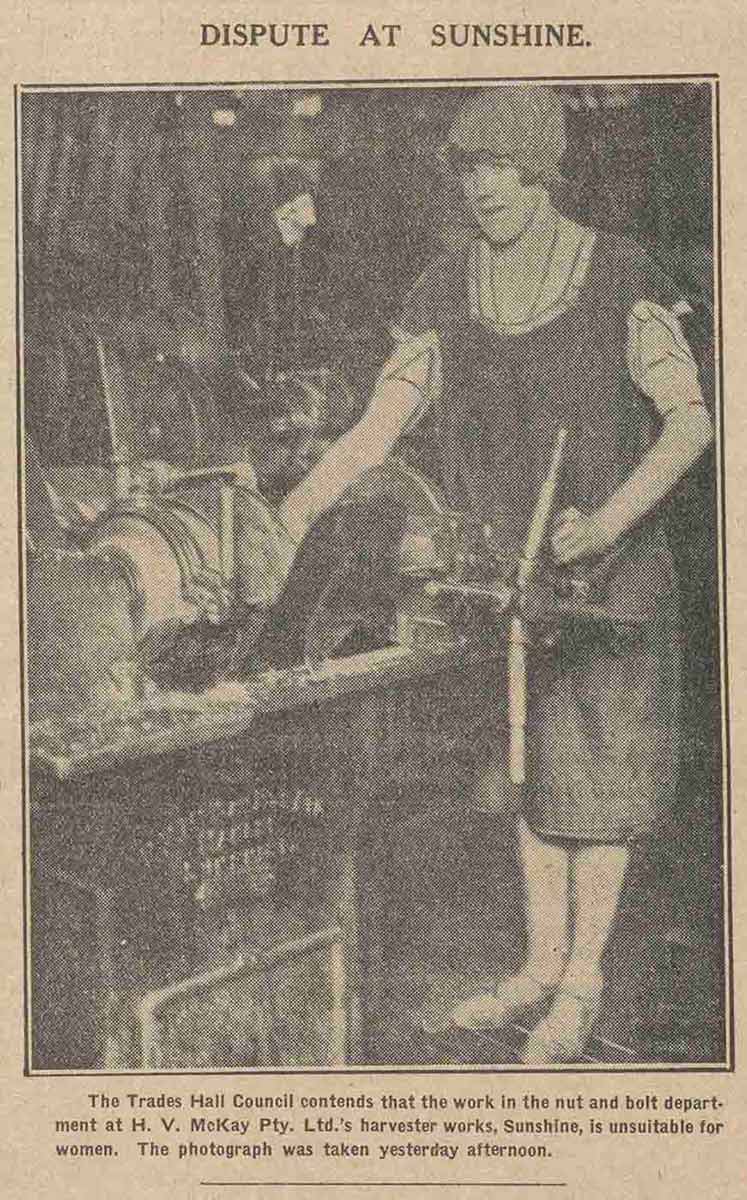

Employing women

From 1922 the Sunshine Harvester Works employed women on the factory floor, beginning in the bolt shop. The employment of women caused uproar in the Victorian Trades Hall Council, the peak body for unions, as it believed women were taking men’s jobs. It also considered factory work too dirty and strenuous for women.

In 1927 the Victorian Government undertook an inquiry into the effects of factory working conditions on women’s and children’s health. Led by Dr Kate McKay, the inquiry found that there were no health reasons to exclude women from the metal trades. It did highlight unequal rates of pay between men and women, stating that pay rates should be equal.

Text below photograph

The Trades Hall Council contends that the work in the nut and bolt department at H.V. McKay Pty. Ltd’s harvester works, Sunshine, is unsuitable for women. The photograph was taken yesterday afternoon.

Excerpt from a letter written by Sunshine Harvester works superintendent George McKay to the Melbourne Argus, 19 September 1922

Transcript

The short facts are that the work done by girls is in this case more satisfactory than it was when the boys did it. The girls are more careful, and produce a better quality of work. The rates of pay are similar, and they take better care of the machines. There is also less waste of time and material. As for the nature of the work, it is not arduous, and certainly not dirtier than that of the housewife, who washes overalls and other soiled garments. As for the motive alleged by the objectors, that is purely gratuitous assumption.

Explore more on Sunshine Harvester Works