Bark painting, as practised by Aboriginal artists of Arnhem Land for millennia, is one of the great traditions of world art.

Old Masters: Australia’s Great Bark Artists showcases the work of 40 master painters who carried one of the oldest continuing traditions of art into the modern era.

This website includes more than 120 works from artists including Narritjin Maymuru, Yirawala, Mawalan Marika, David Malangi and their contemporaries.

The Old Masters exhibition debuted at the National Museum of Australia in 2013 and the international touring exhibition travelled to China in 2019–20.

This region is dominated by the Arnhem Escarpment, a vast range of rocky hills home to thousands of rock art galleries, some more than 30,000 years old. The majority of rock paintings here are figurative and these have influenced the style of bark painting in the region.

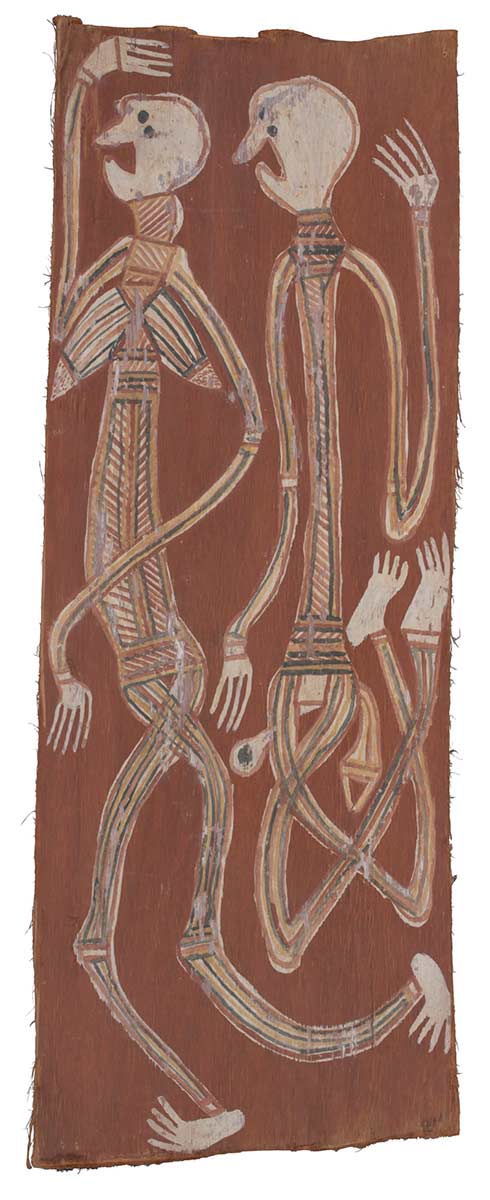

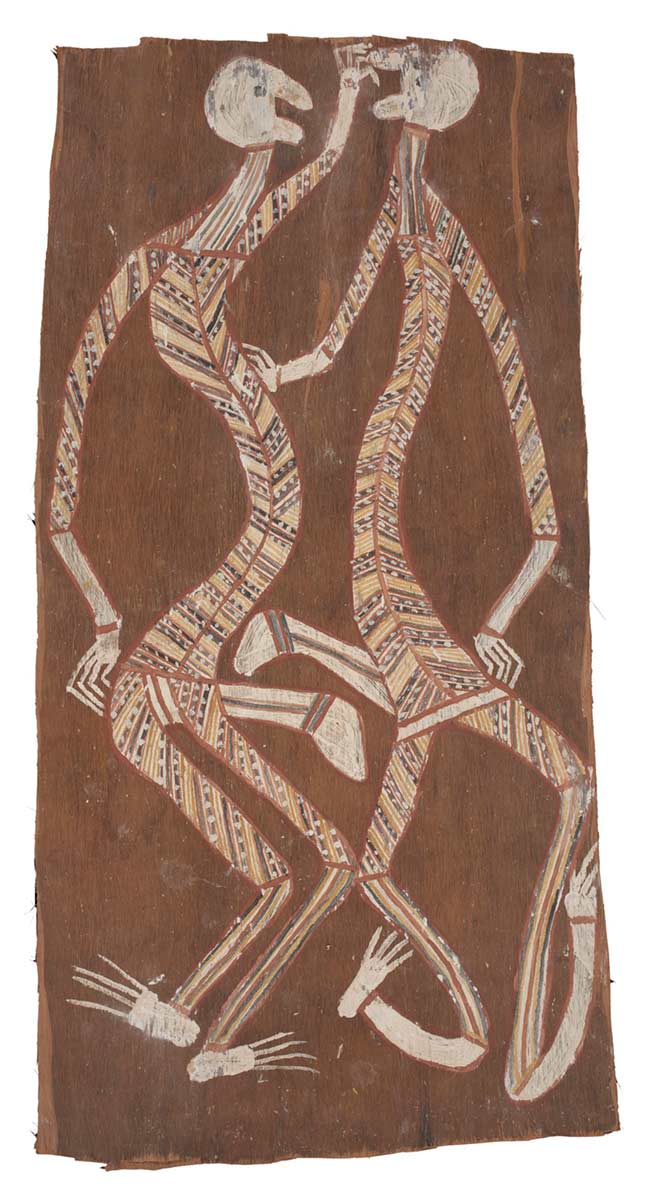

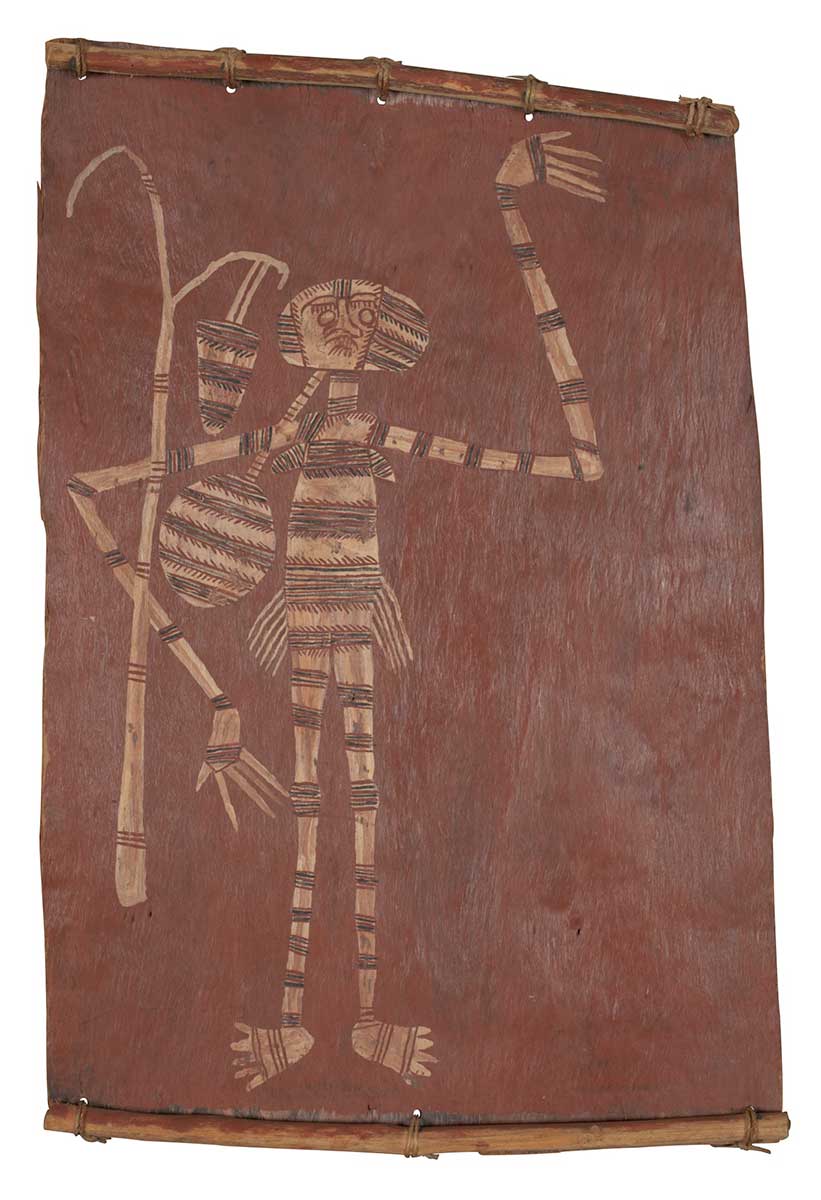

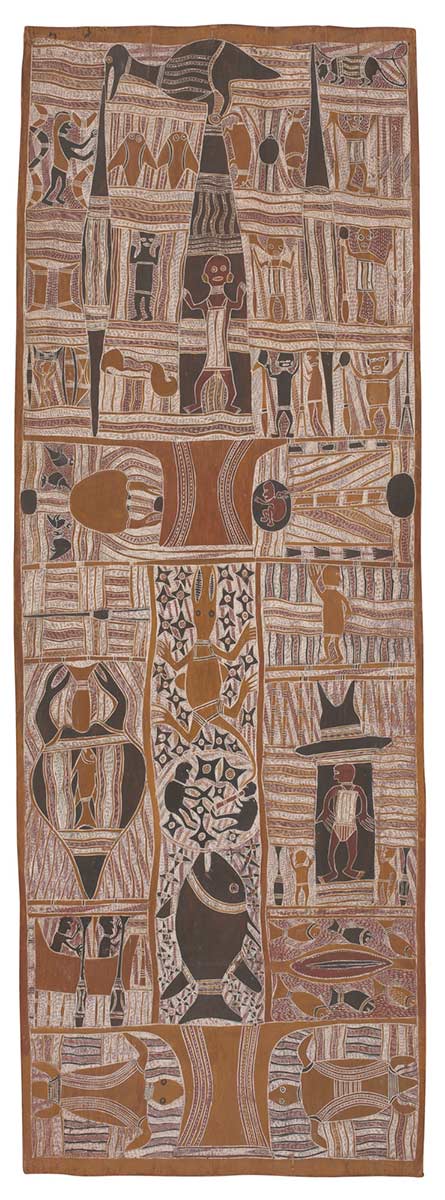

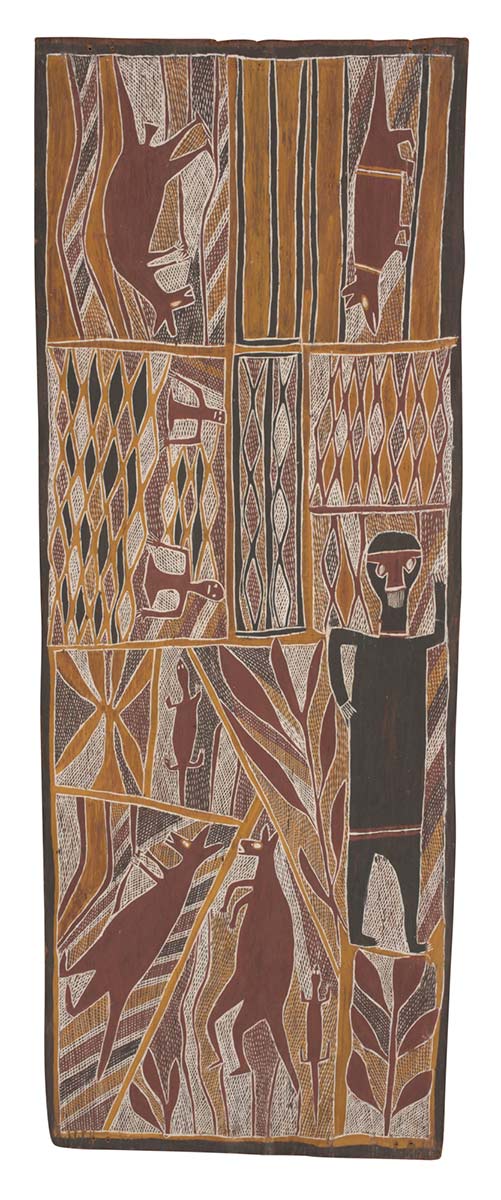

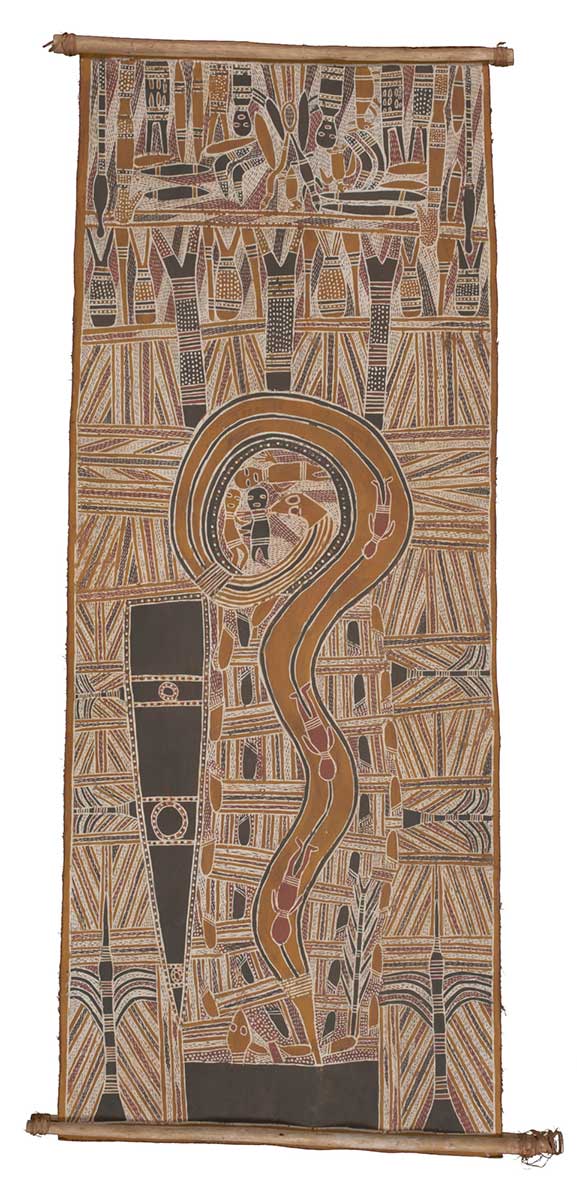

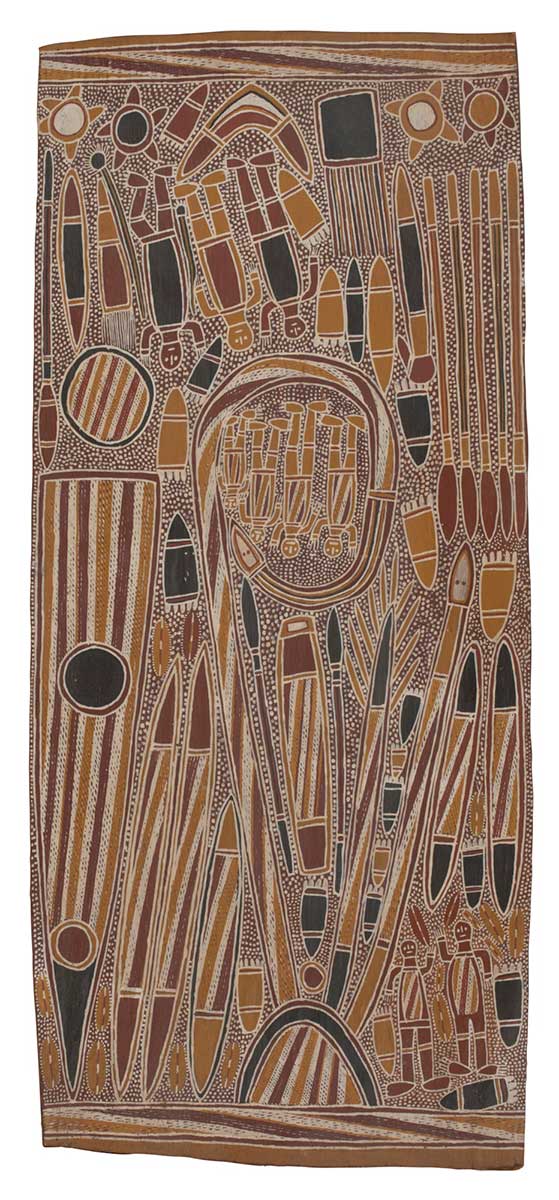

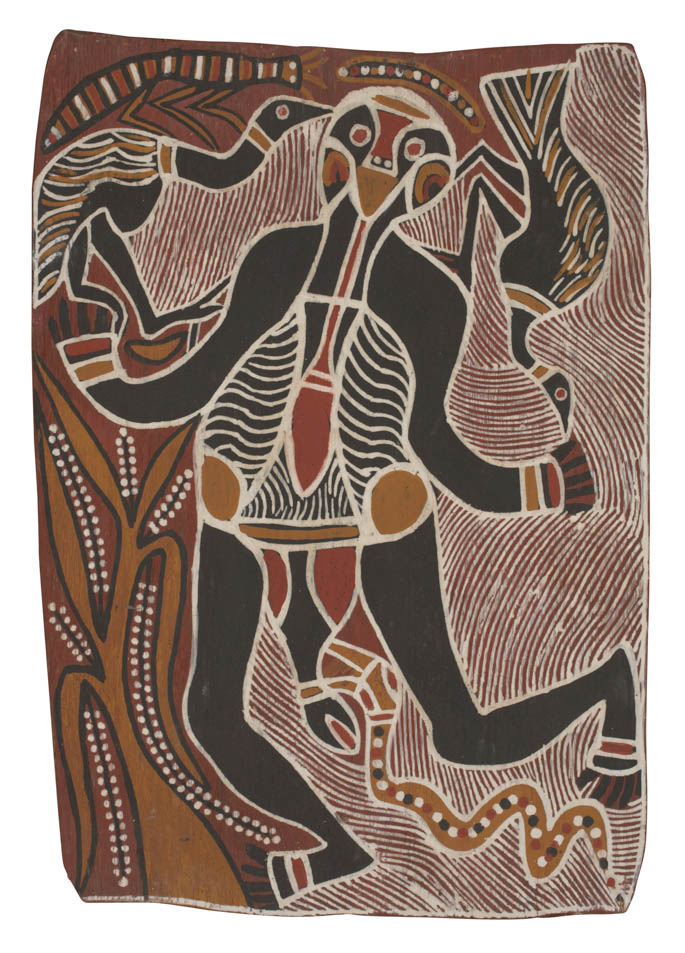

Yirawala is one of the major artists in Australian art history. He played a leading role in promoting the acceptance of Aboriginal art as ‘art’ rather than simply ‘ethnographic material’.

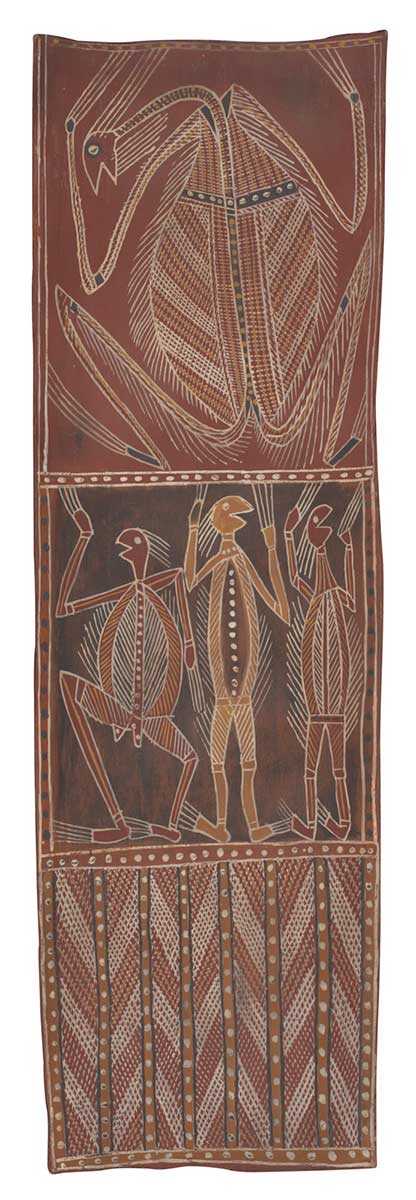

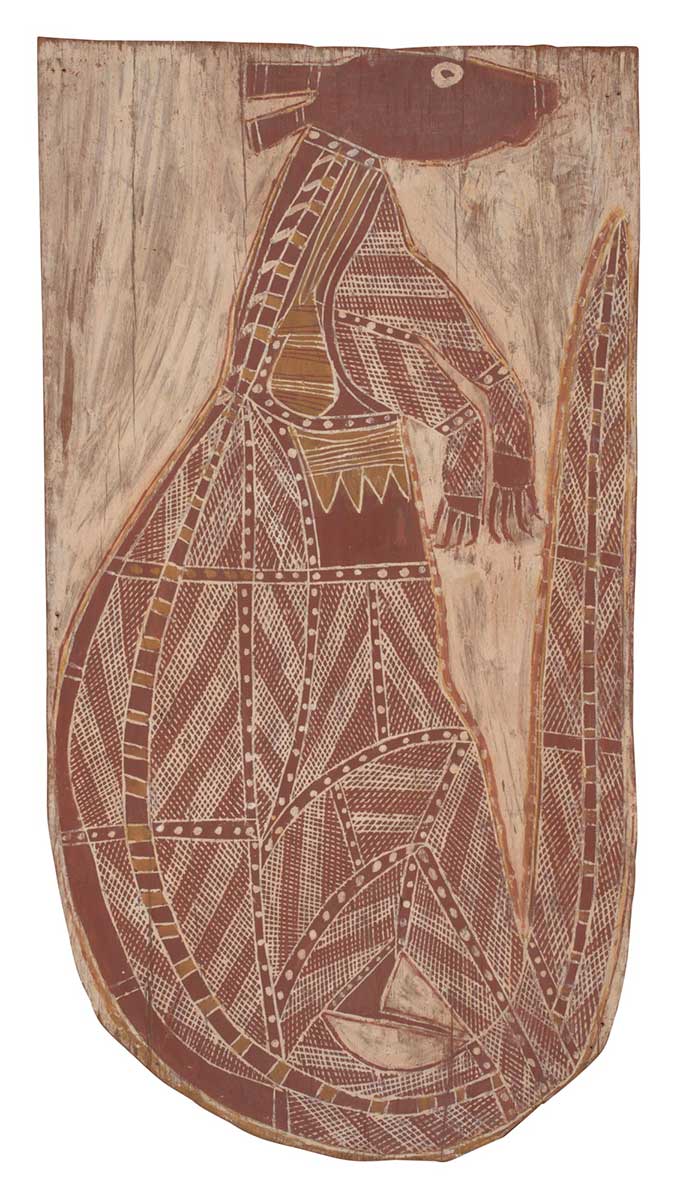

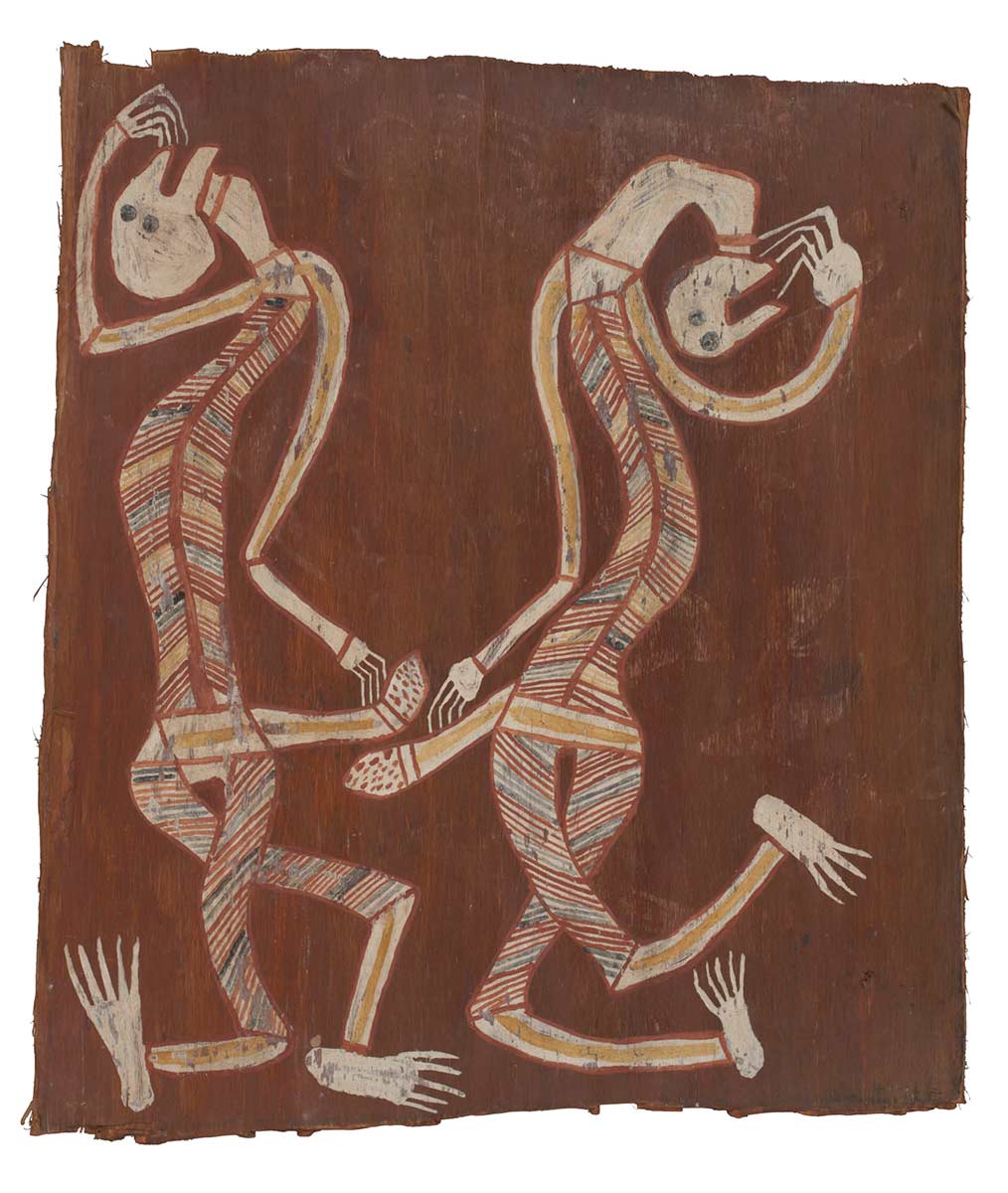

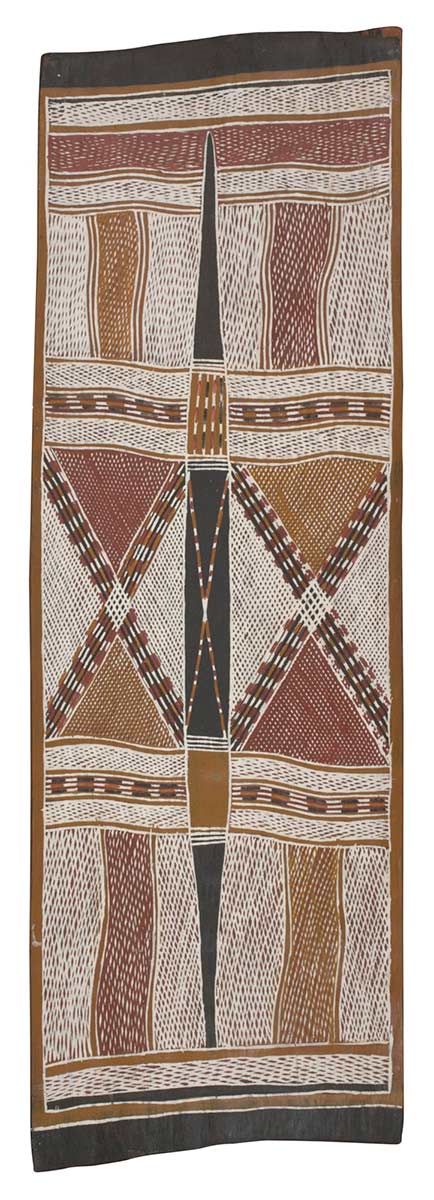

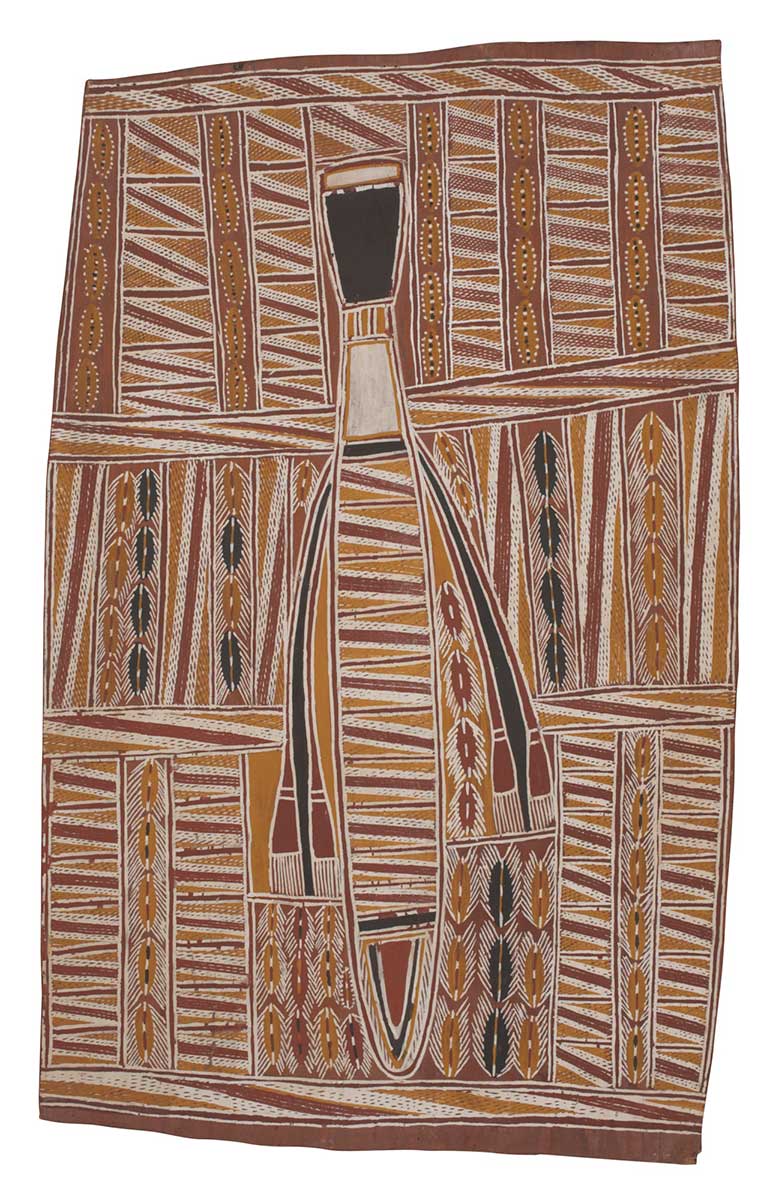

Yirawala’s impetus to paint for the public stemmed from a need to reveal his culture to non-Indigenous Australians so that it could be understood and respected. He was a gifted painter of high ritual authority, which allowed him to innovate on the art traditions of the Kuninjku people. Among his main innovations are his exquisitely rendered variations on conventional rarrk (crosshatched) clan patterns.

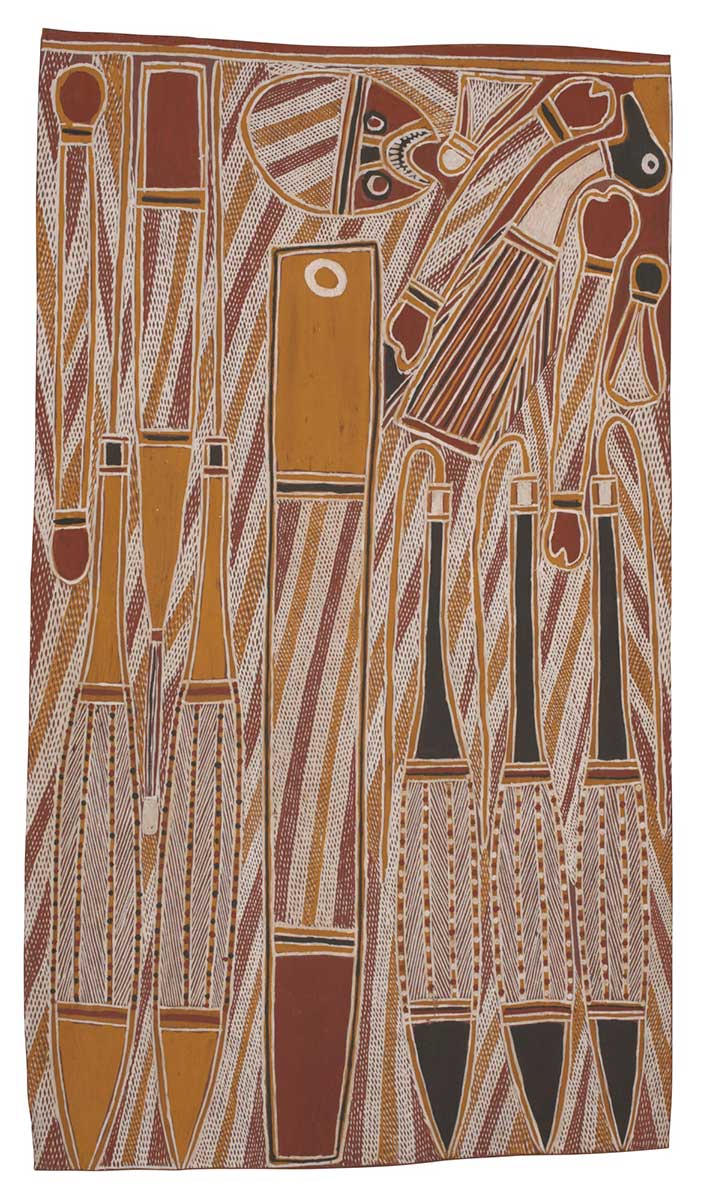

Although Yirawala had an extensive repertoire of subjects at his command, the majority of his work is associated with the major regional ceremonies, especially the Mardayin, which involves both Duwa and Yirridjdja moities.

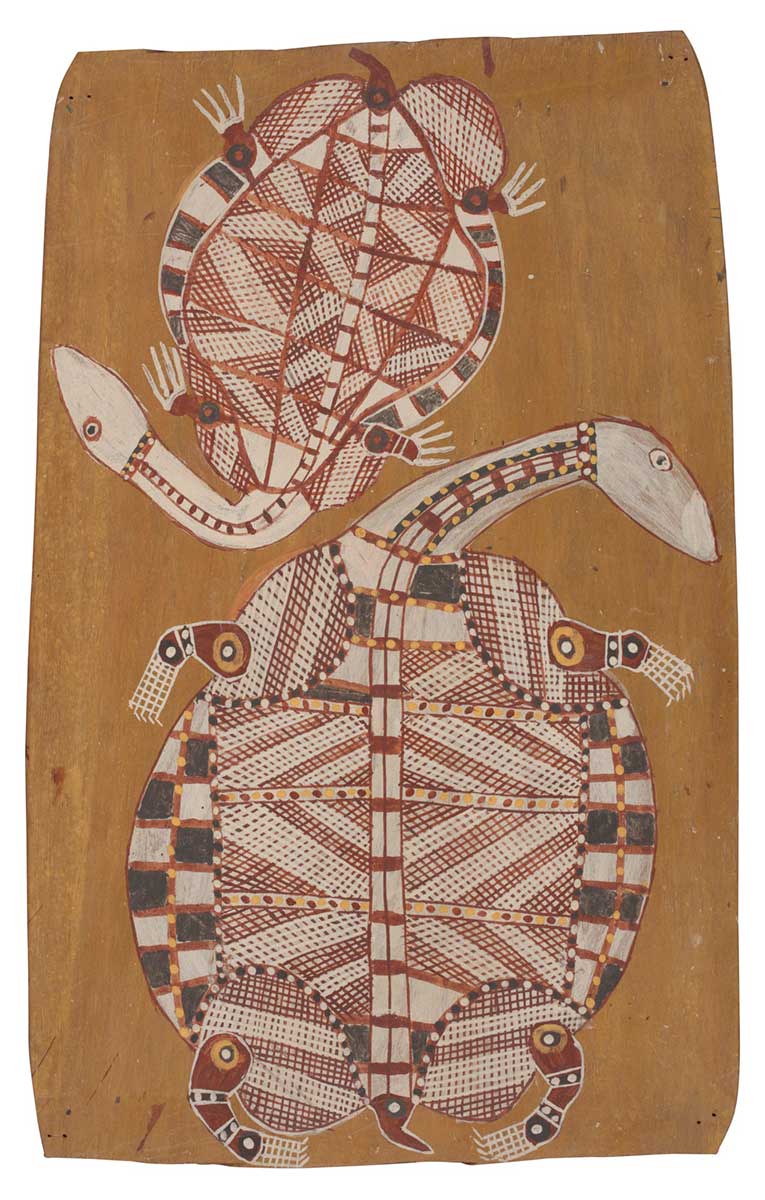

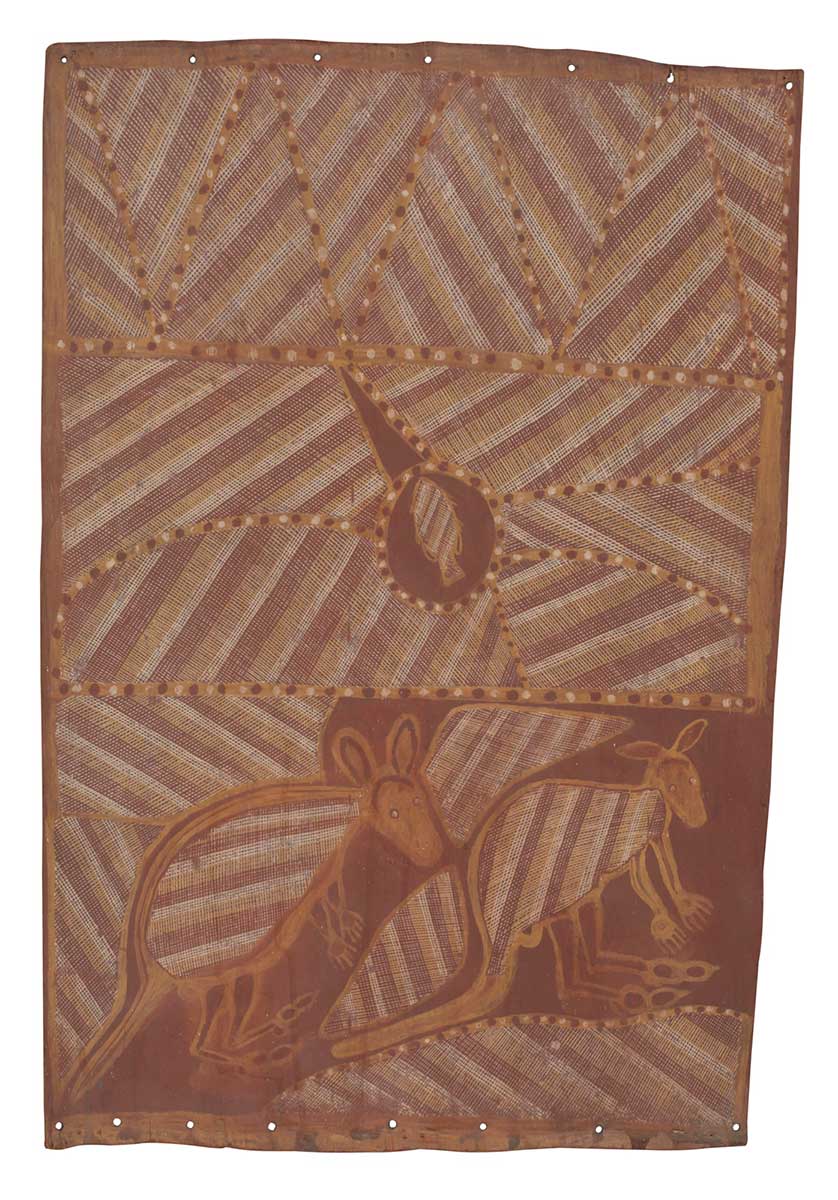

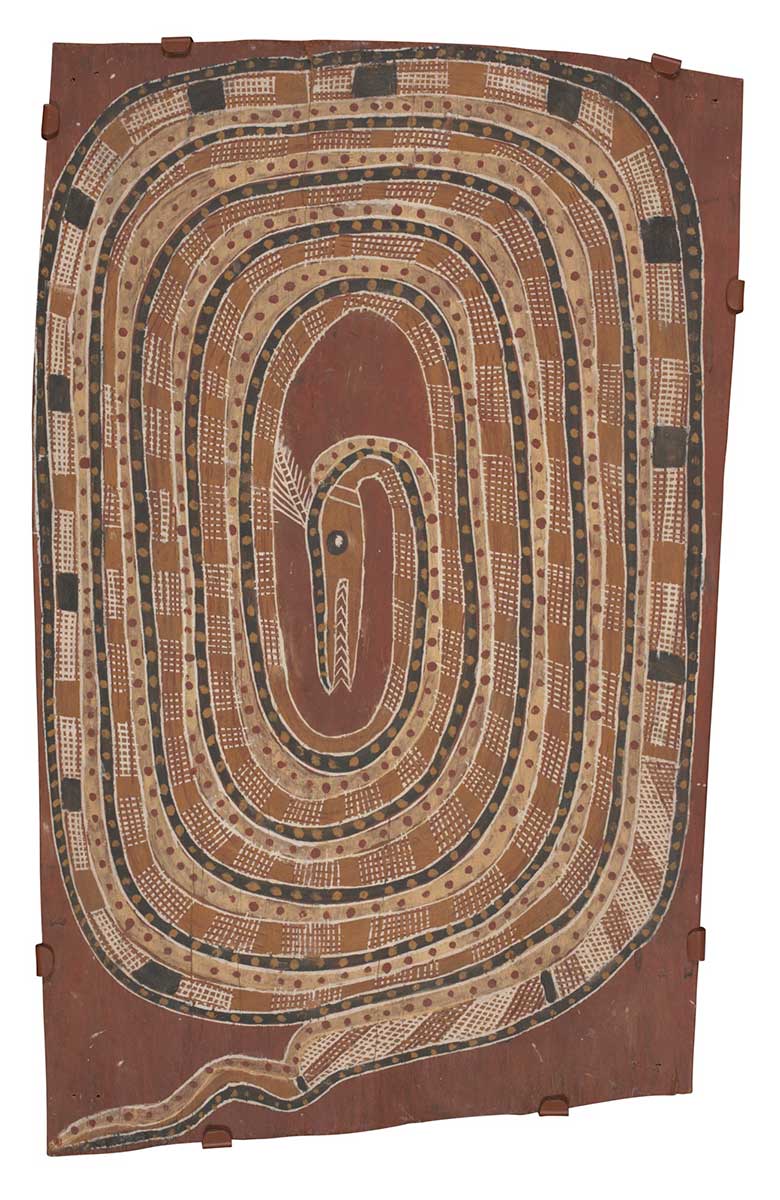

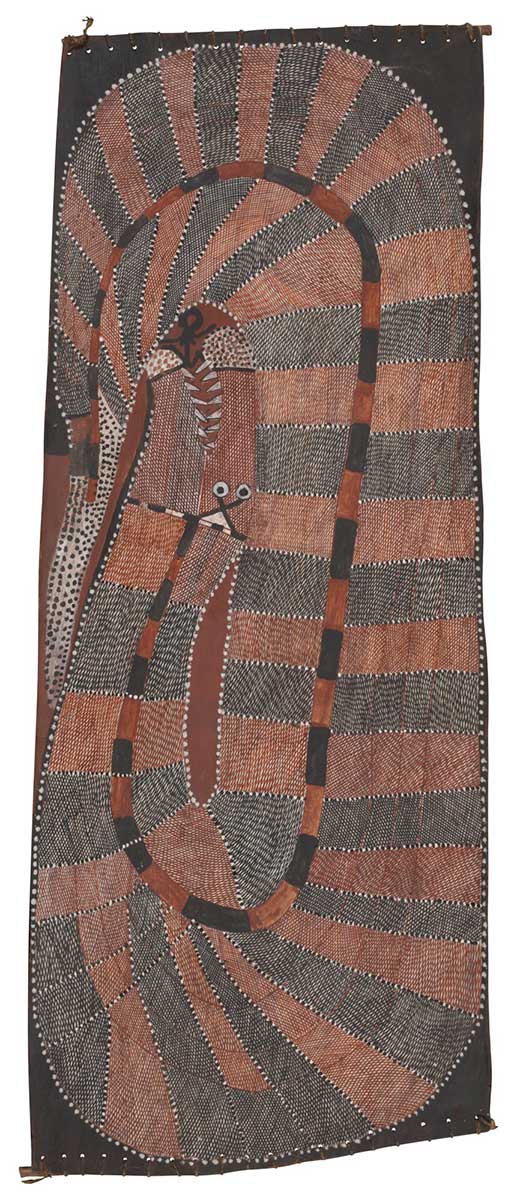

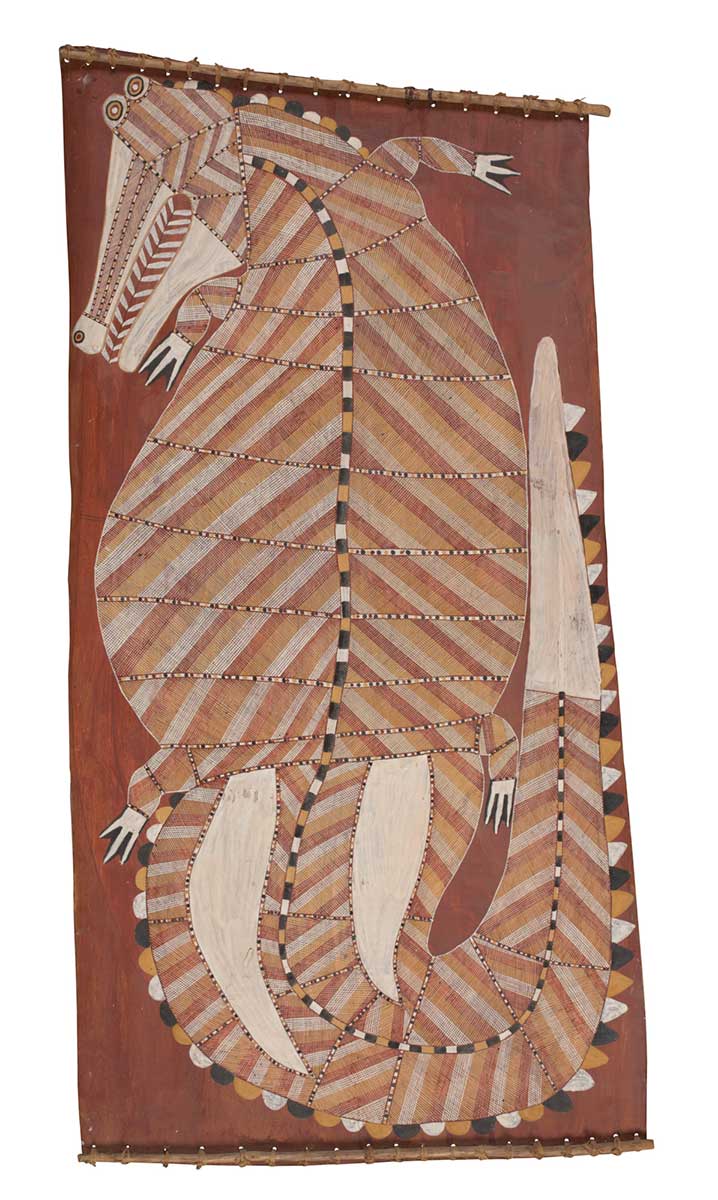

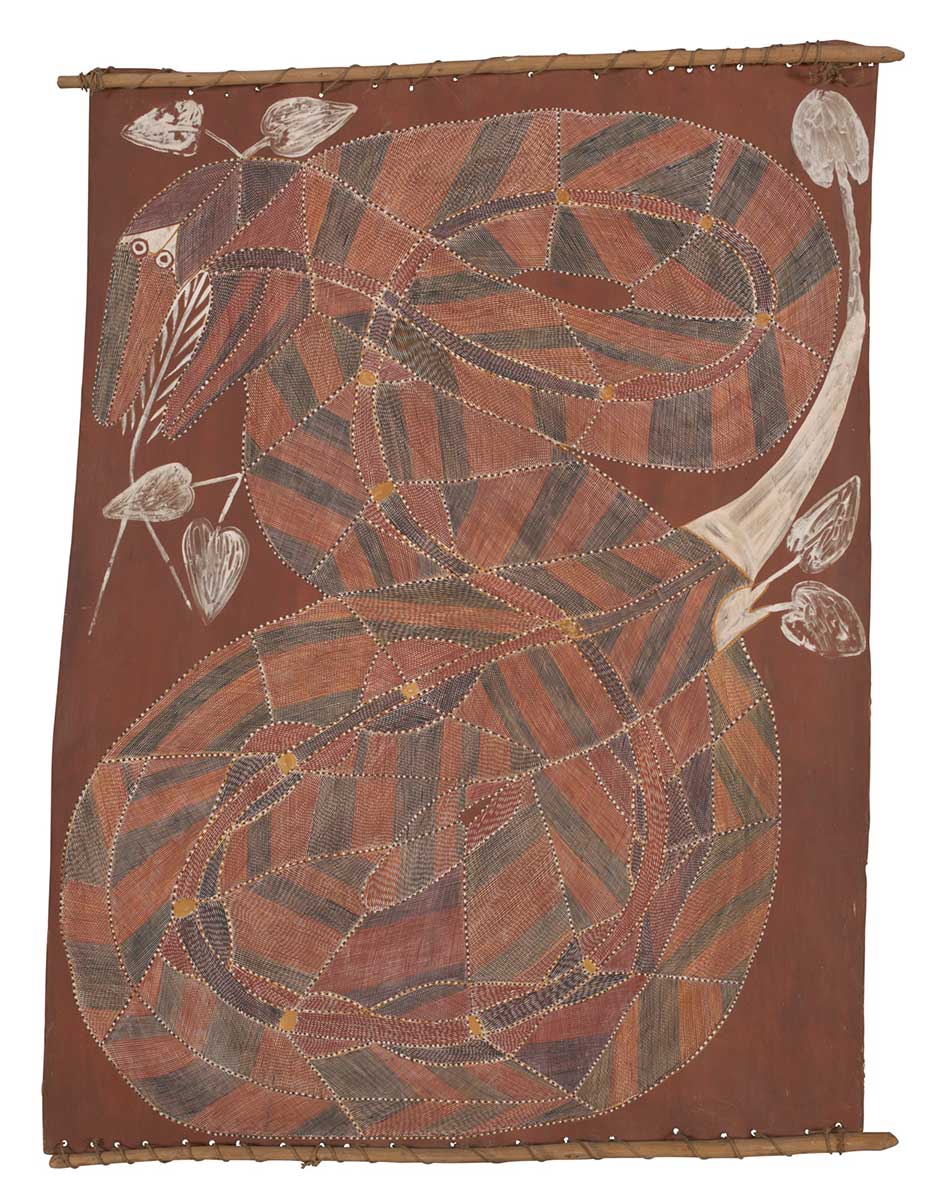

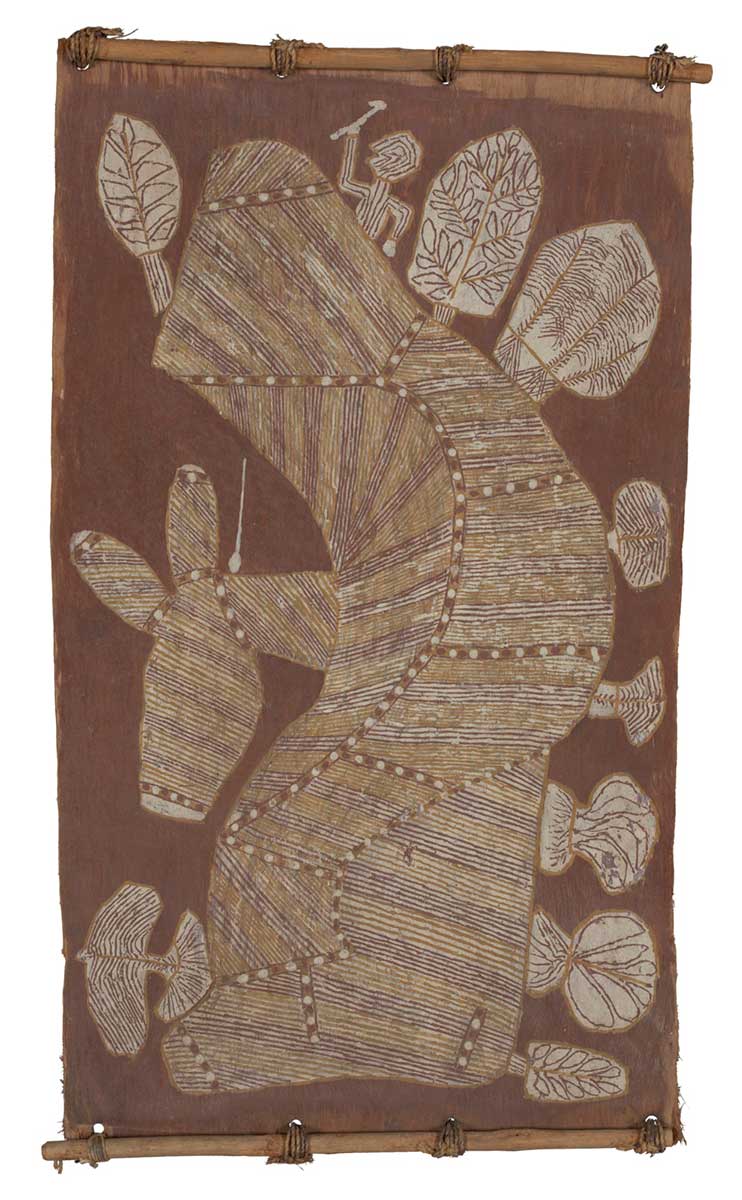

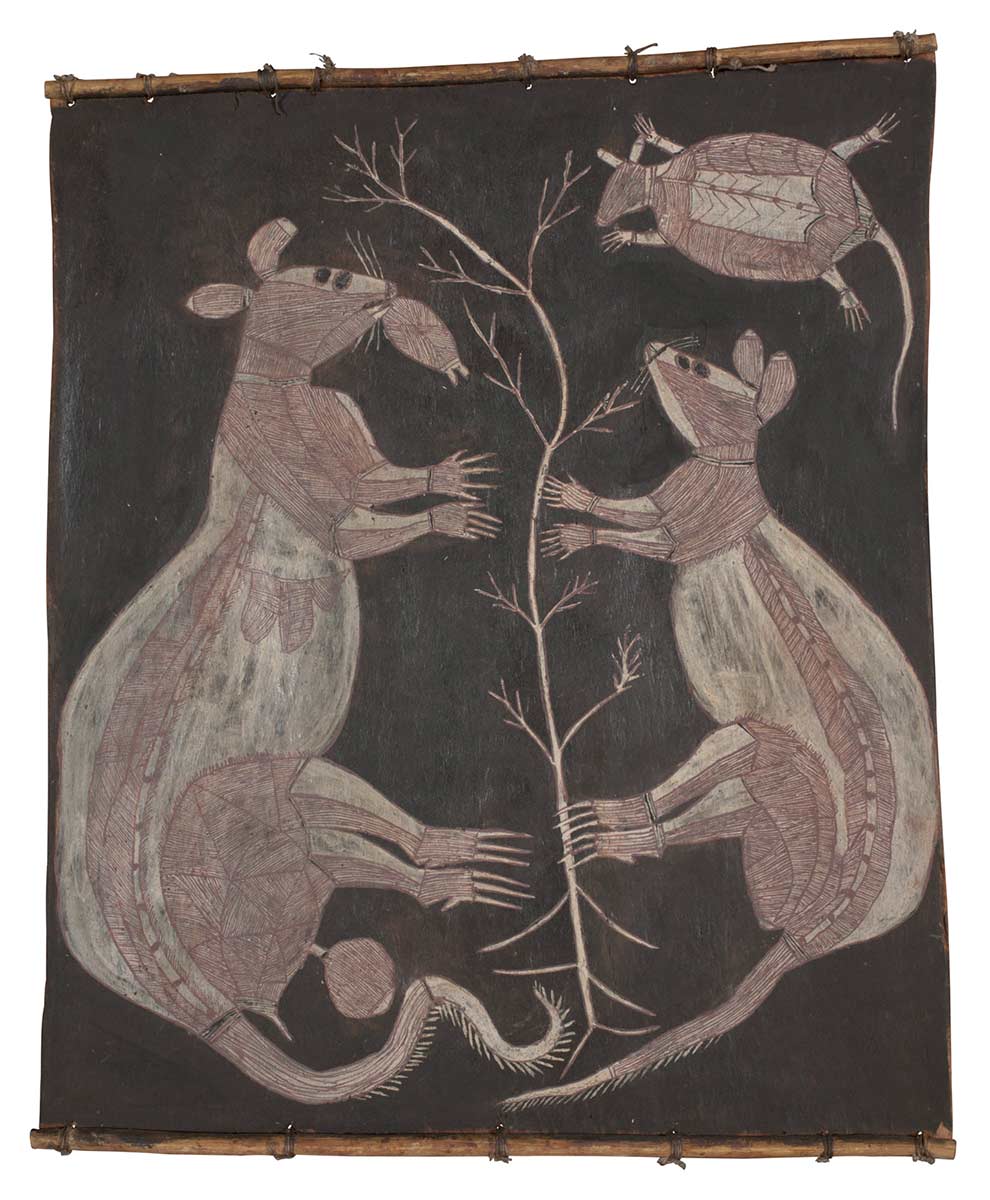

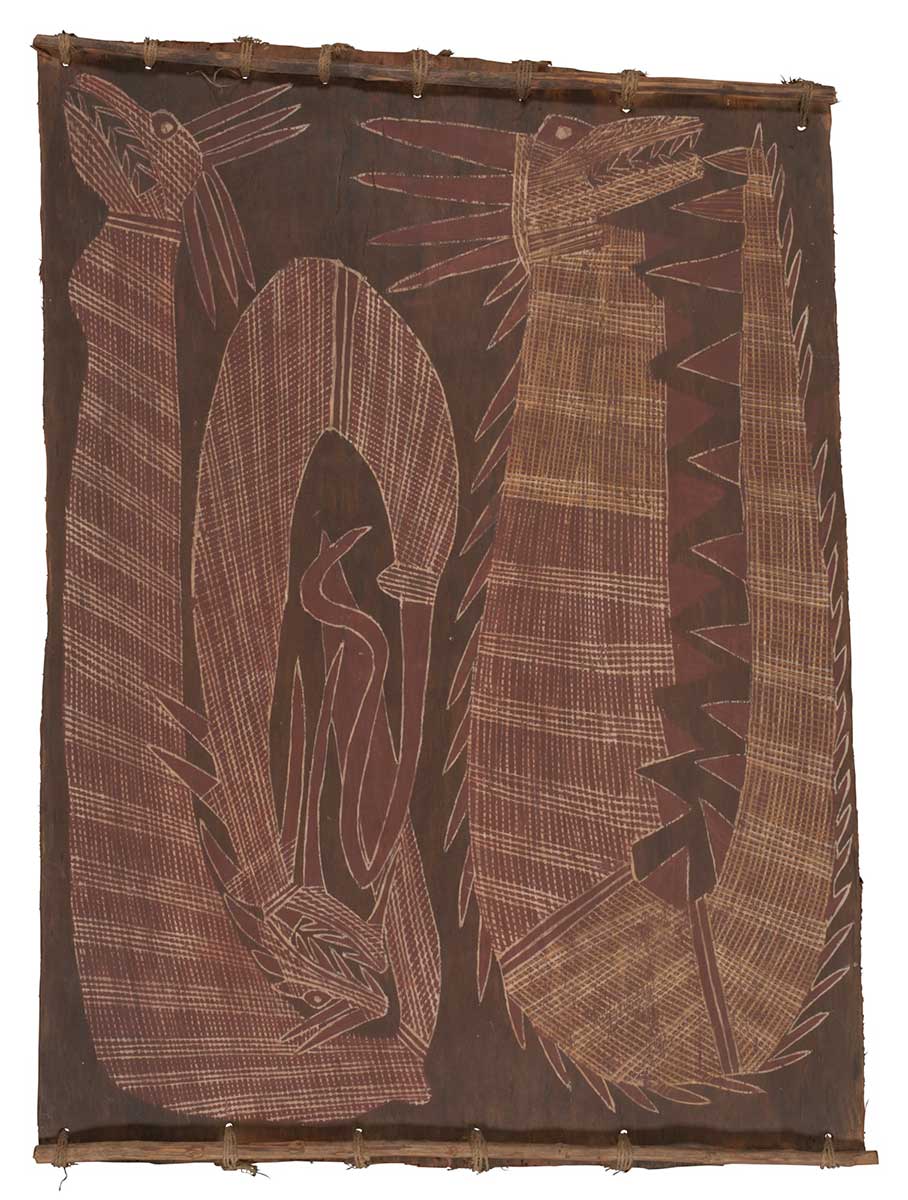

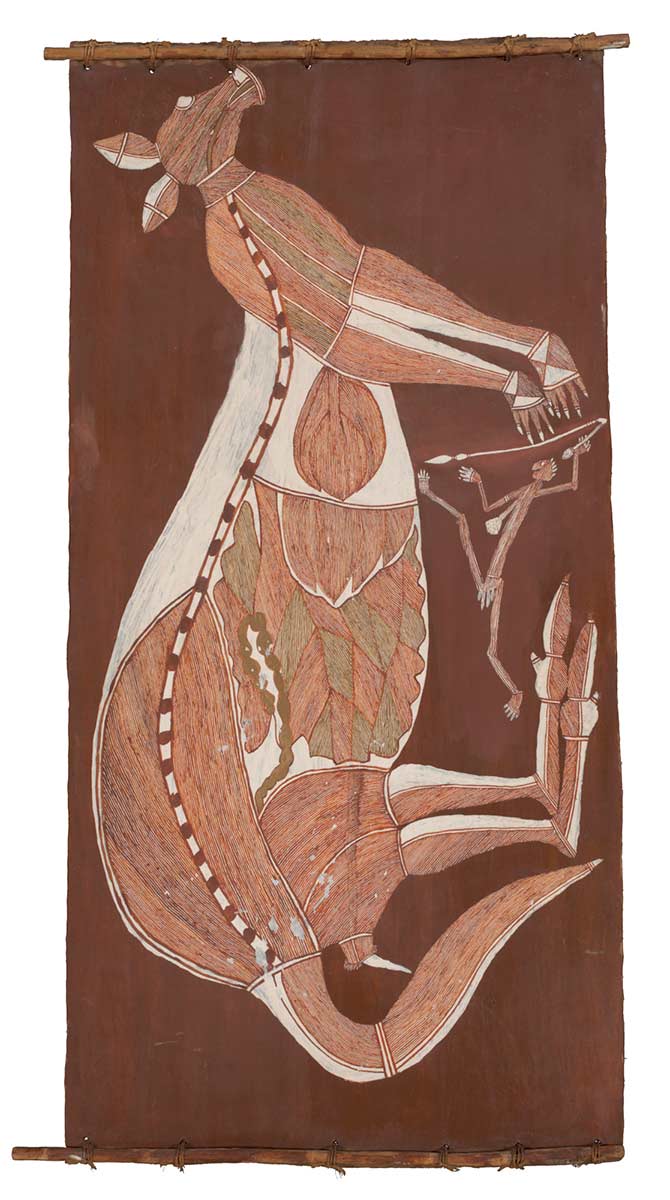

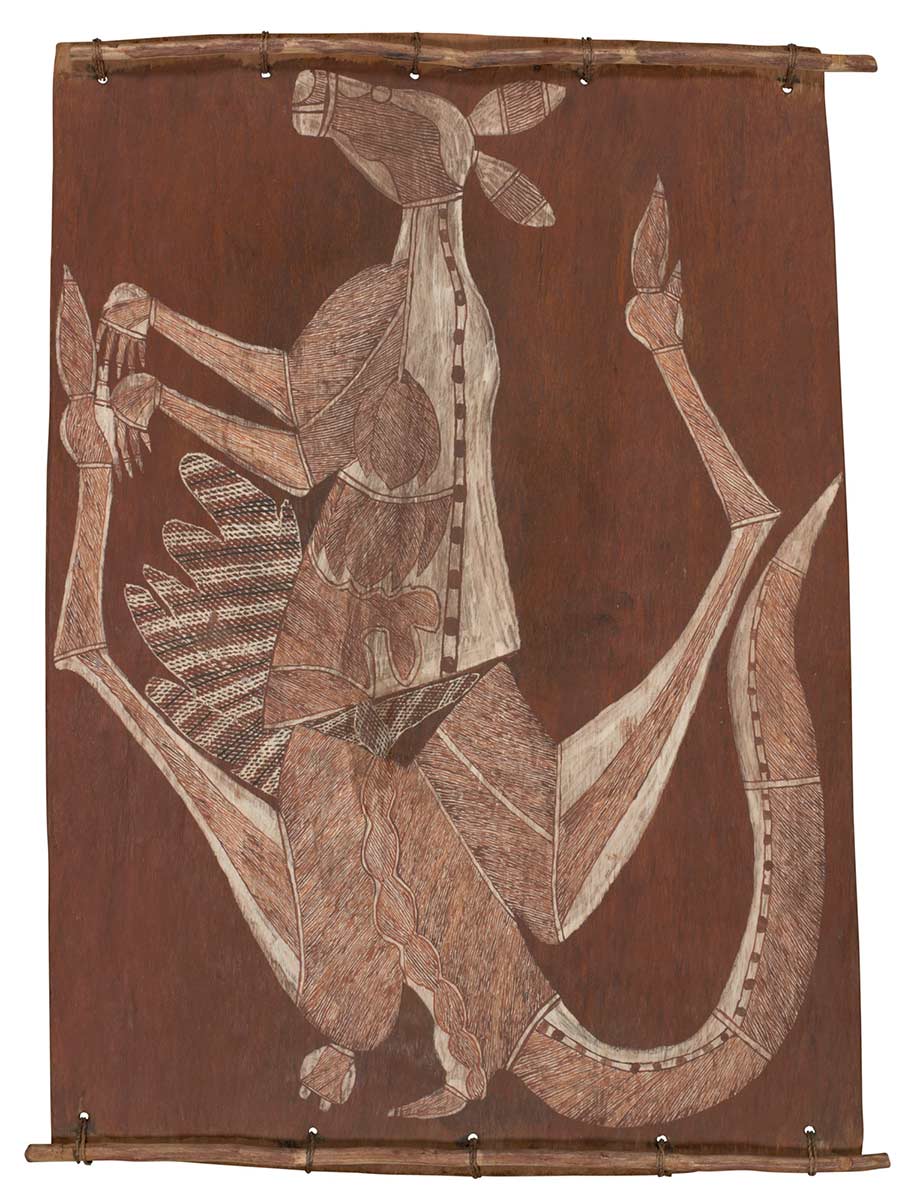

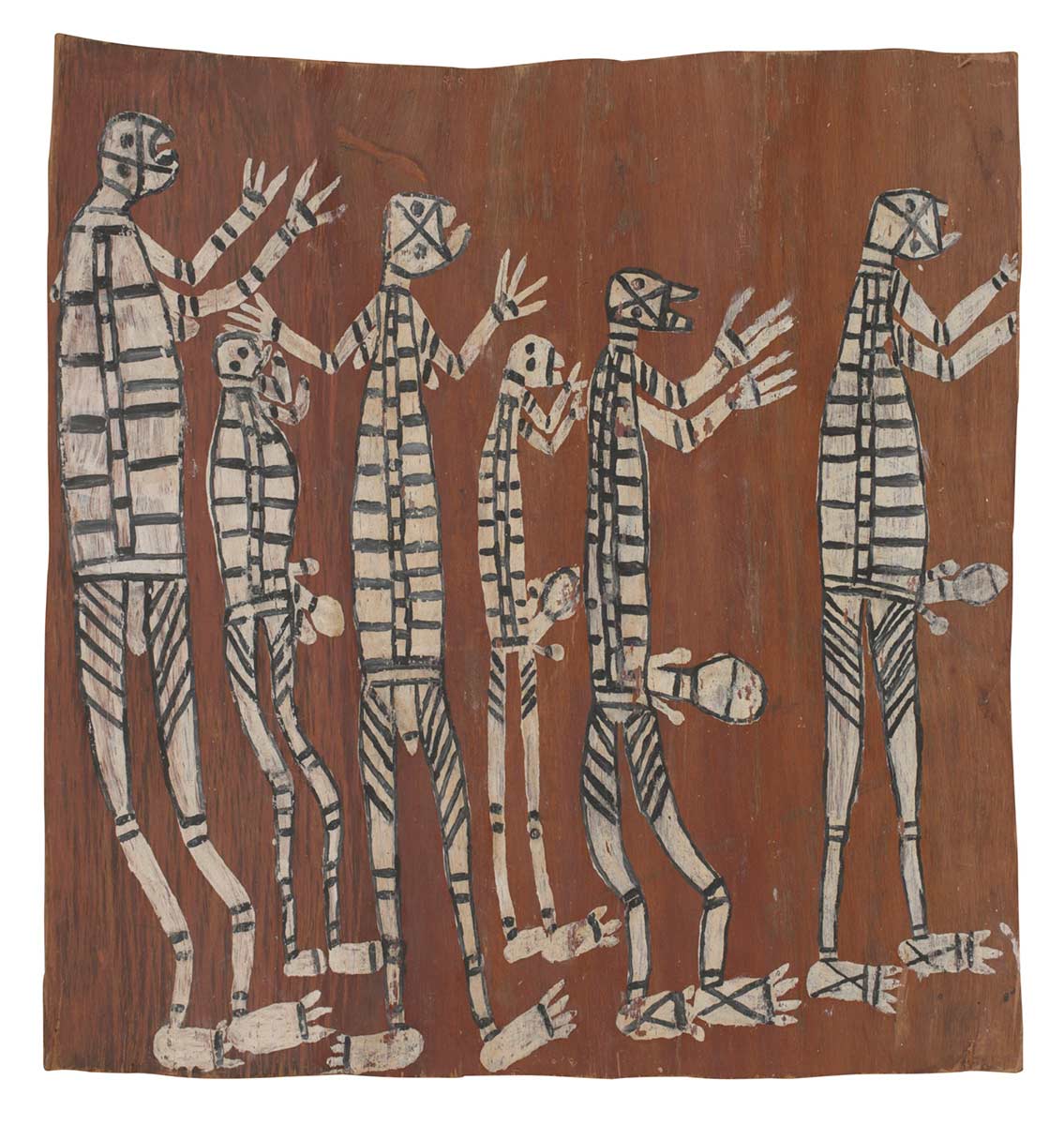

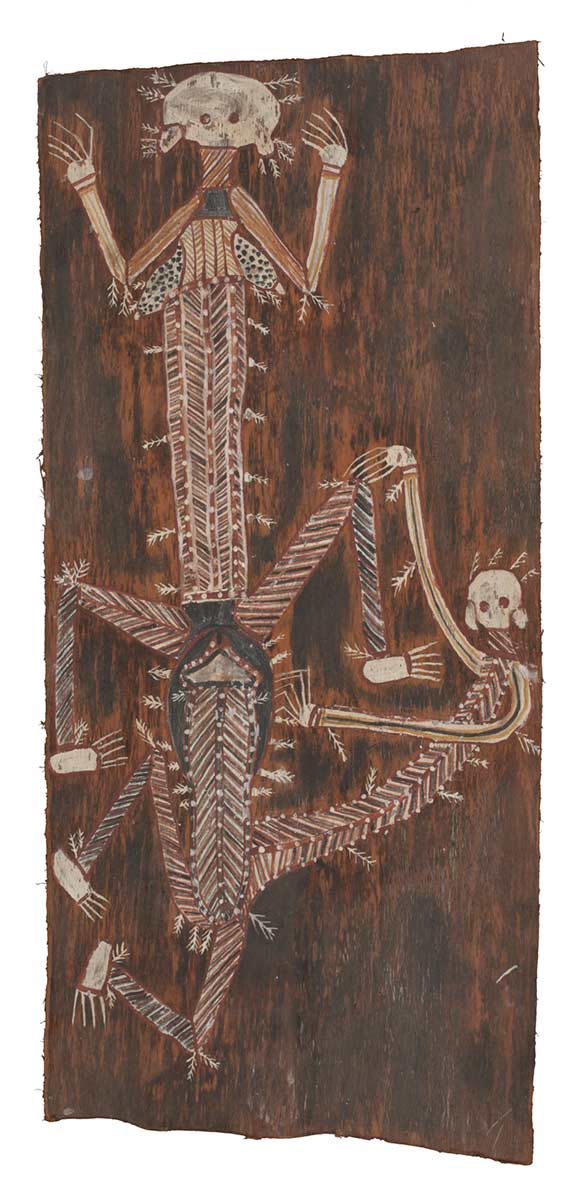

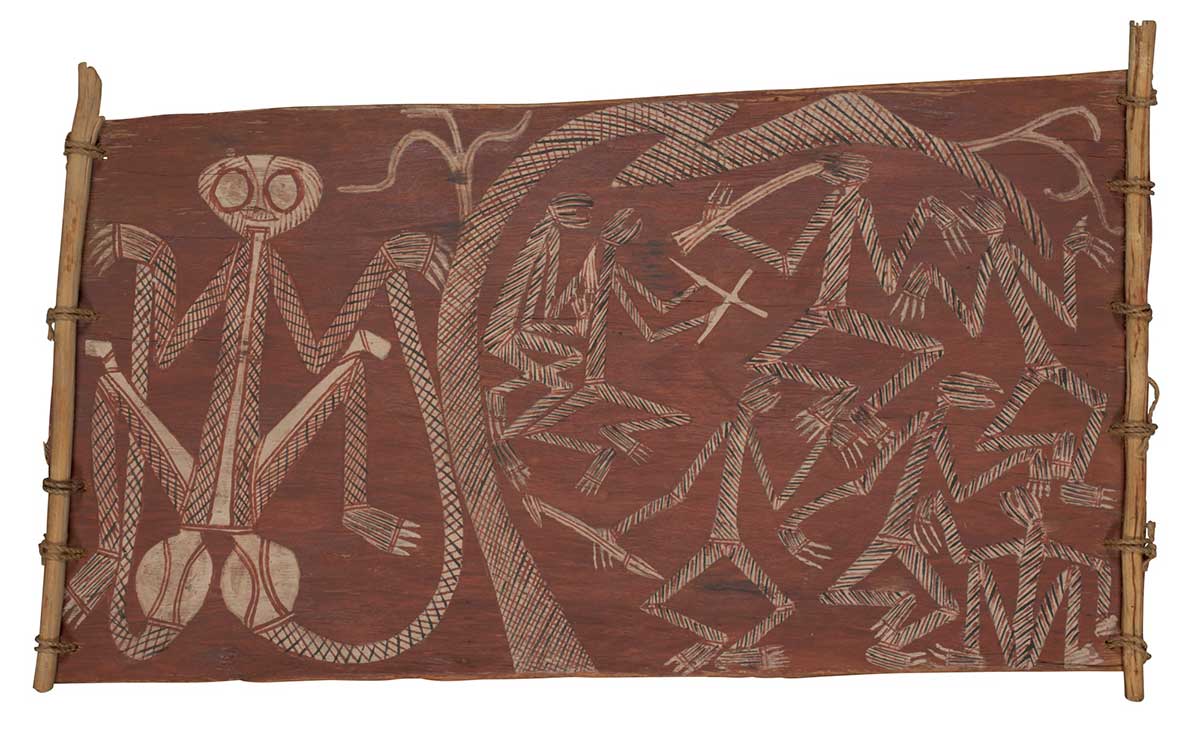

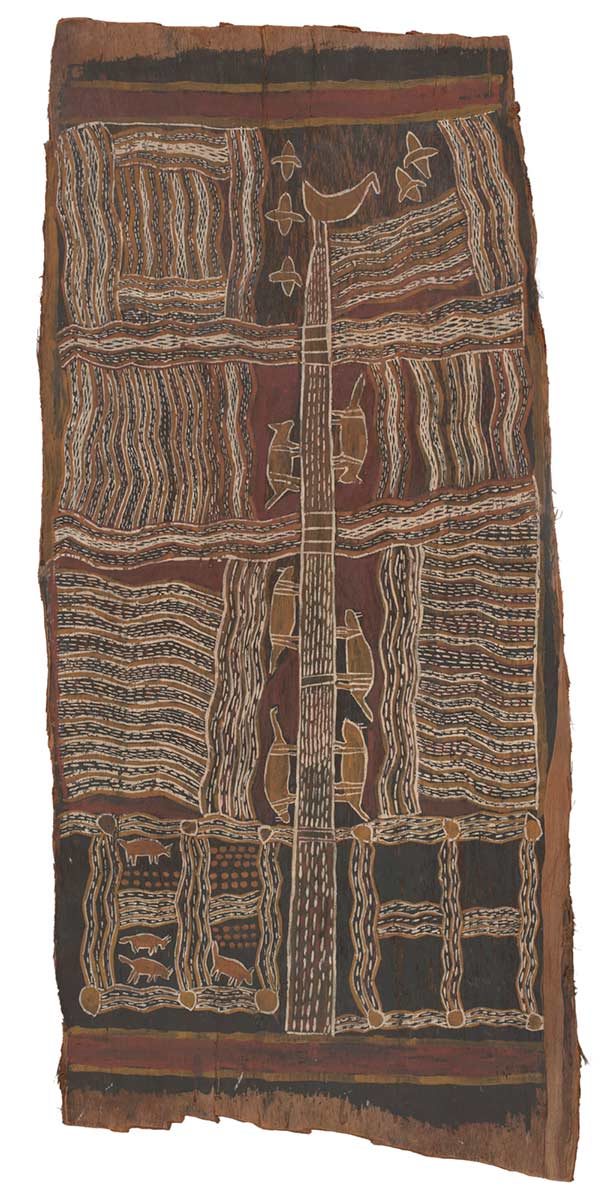

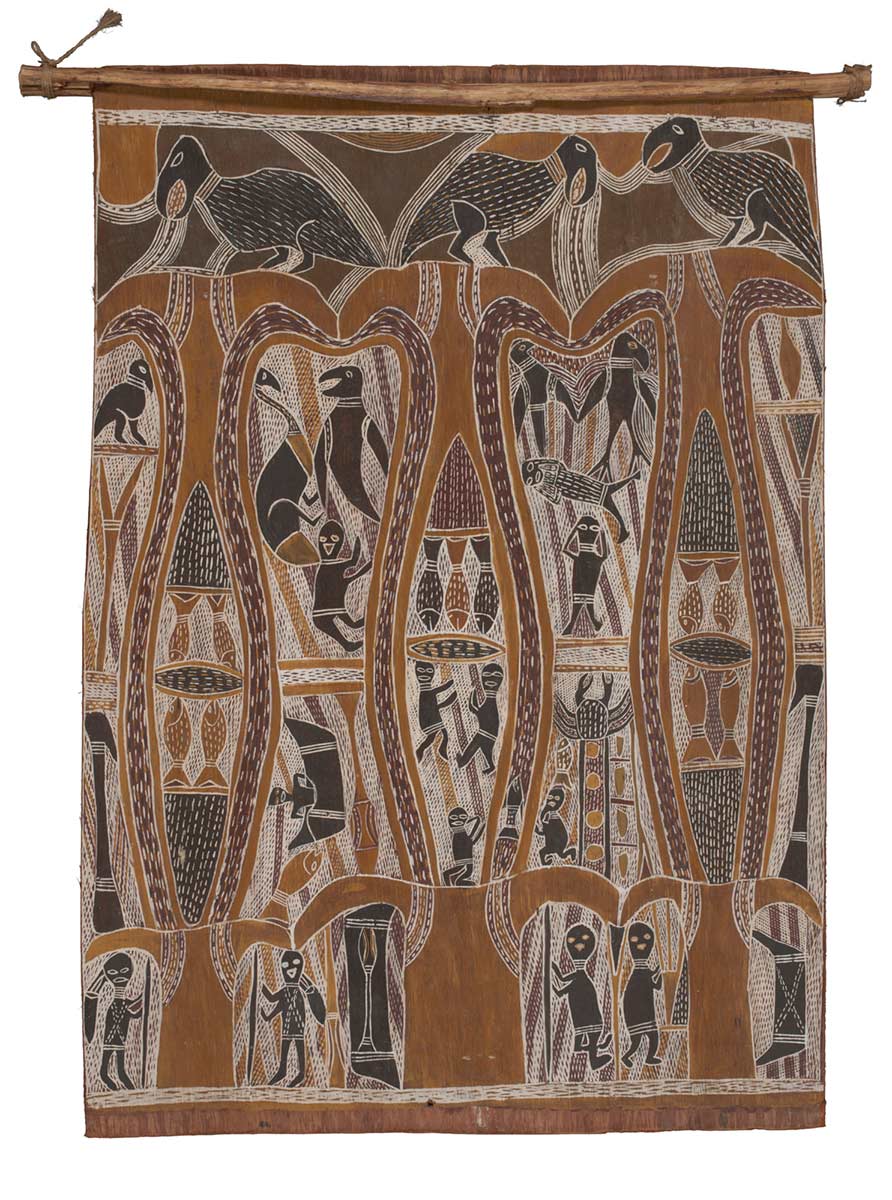

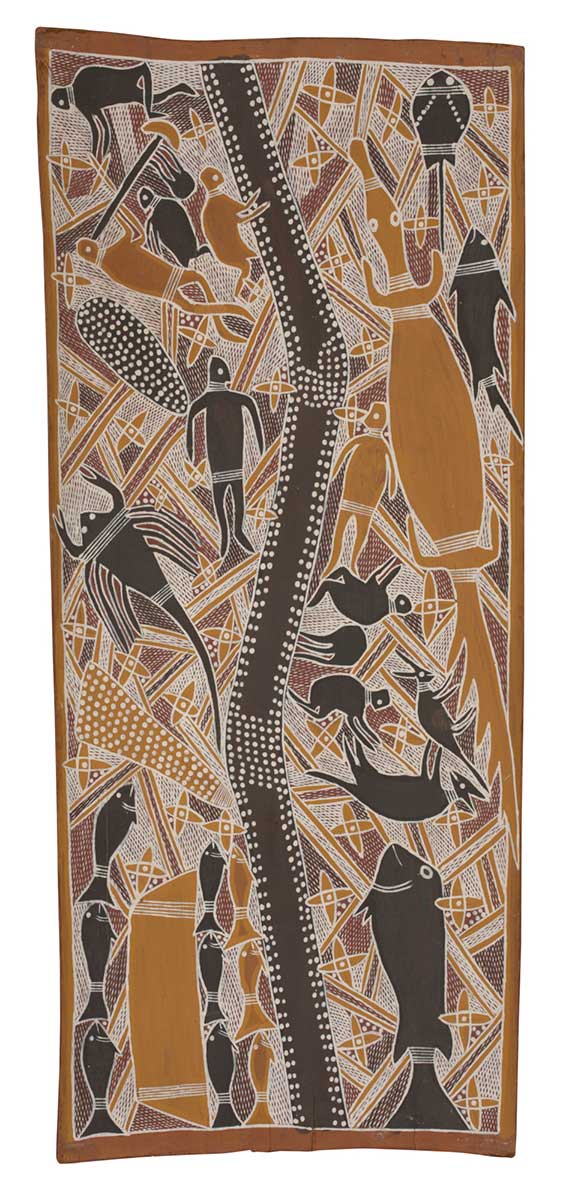

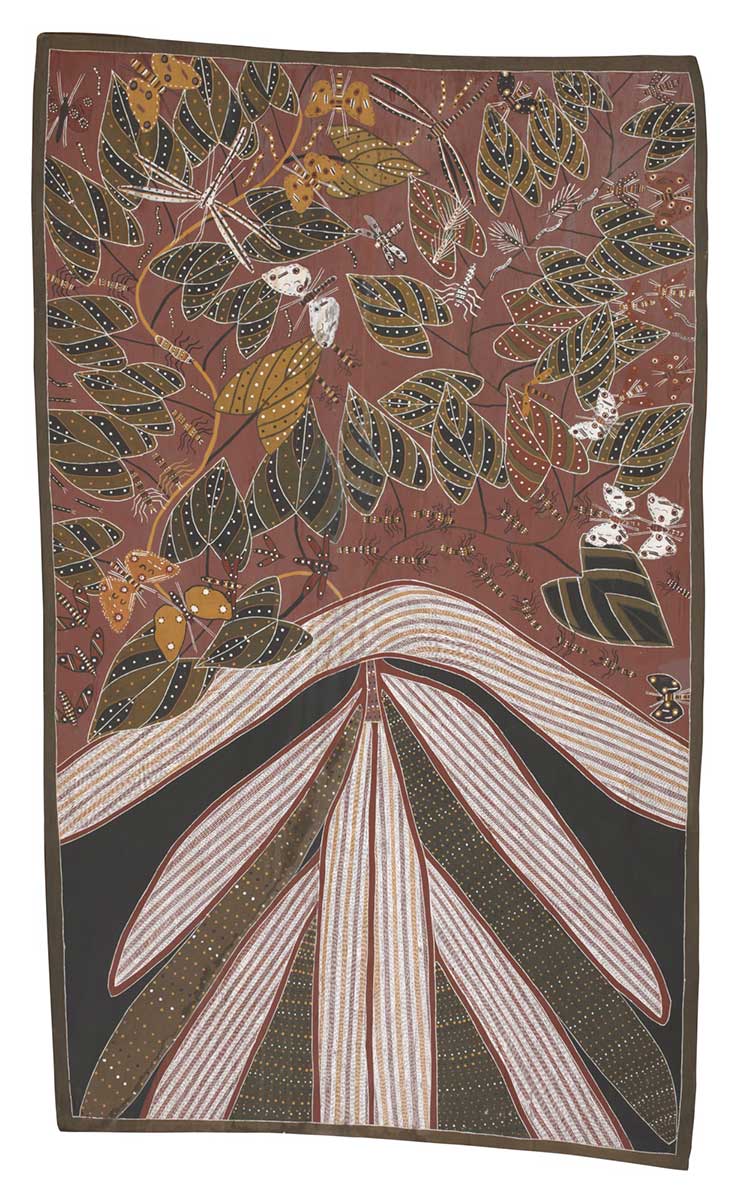

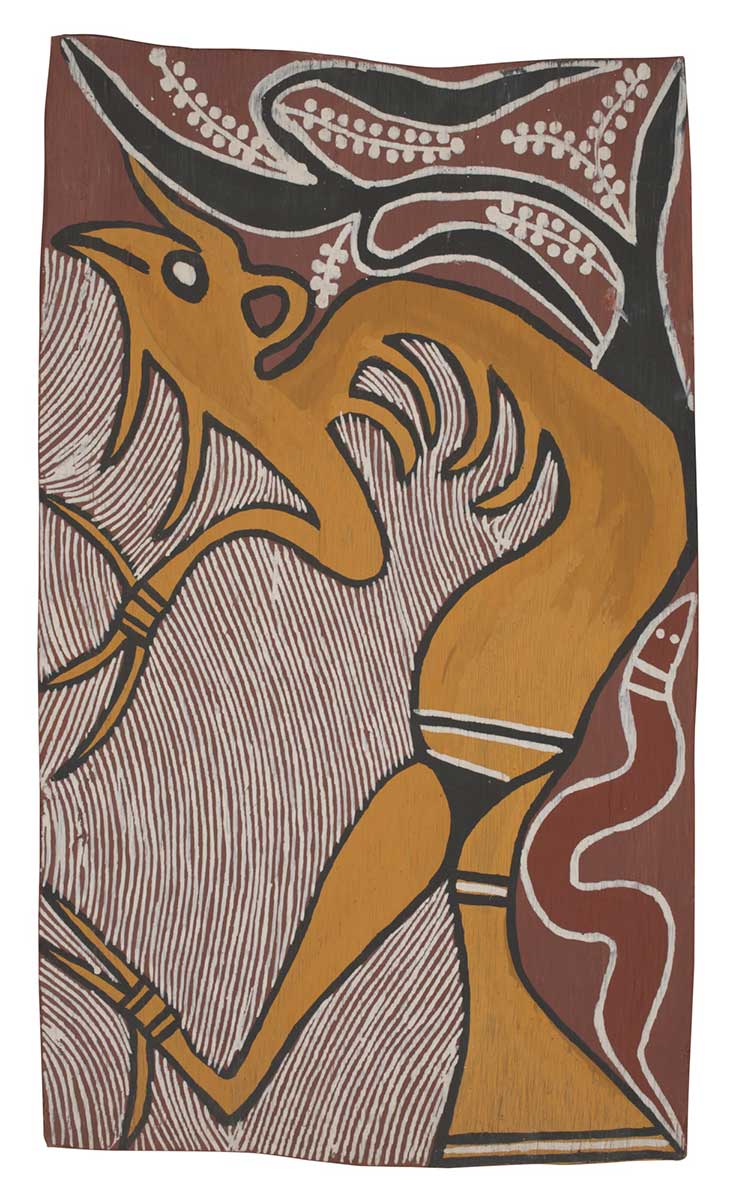

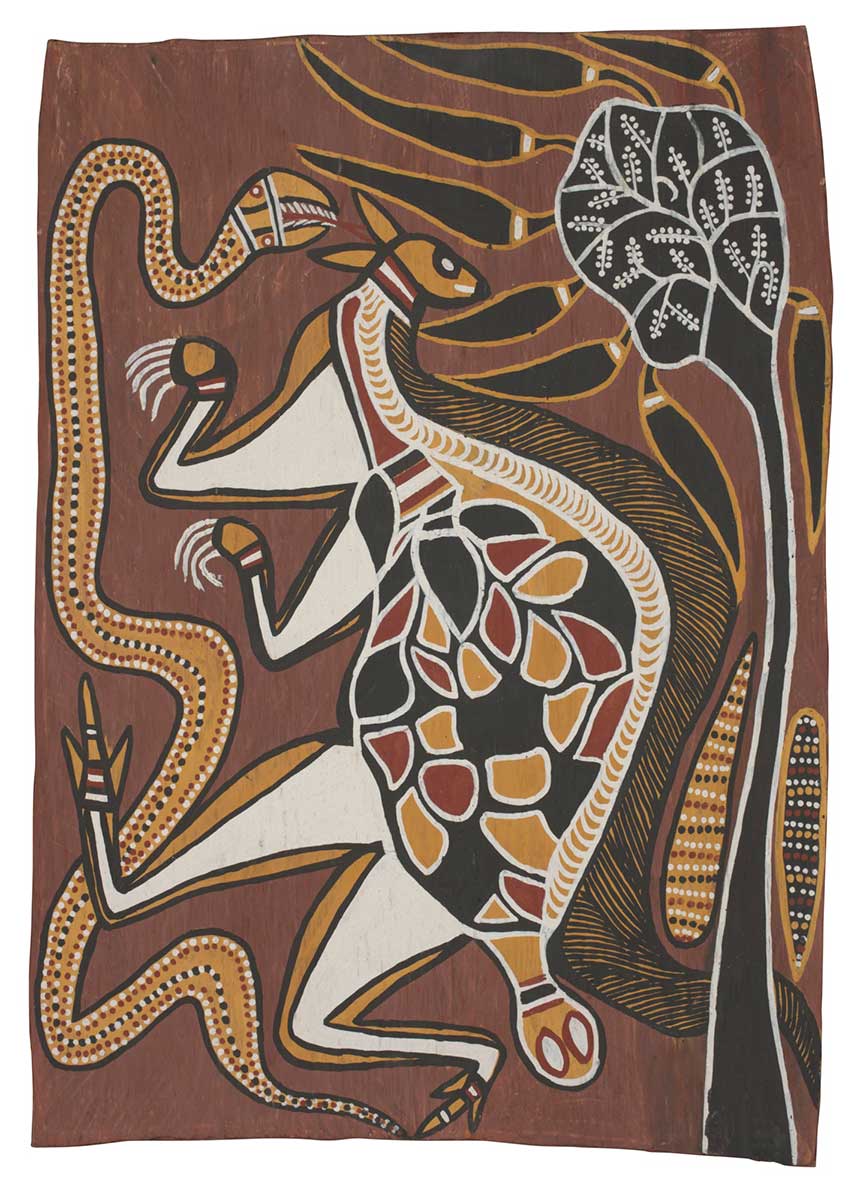

Themes represented in the paintings here include: Ngalyod the Rainbow Serpent, wearing a feather headdress to indicate its connection to ceremony; Lumaluma the Giant Ogre, whose limbs were cut off and transformed into ritual objects; Kandakidj the Antilopine Kangaroo associated with the Wubarr and Lorrkkon ceremonies; Namanjwarre the Estuarine Crocodile; and images of sorcery.

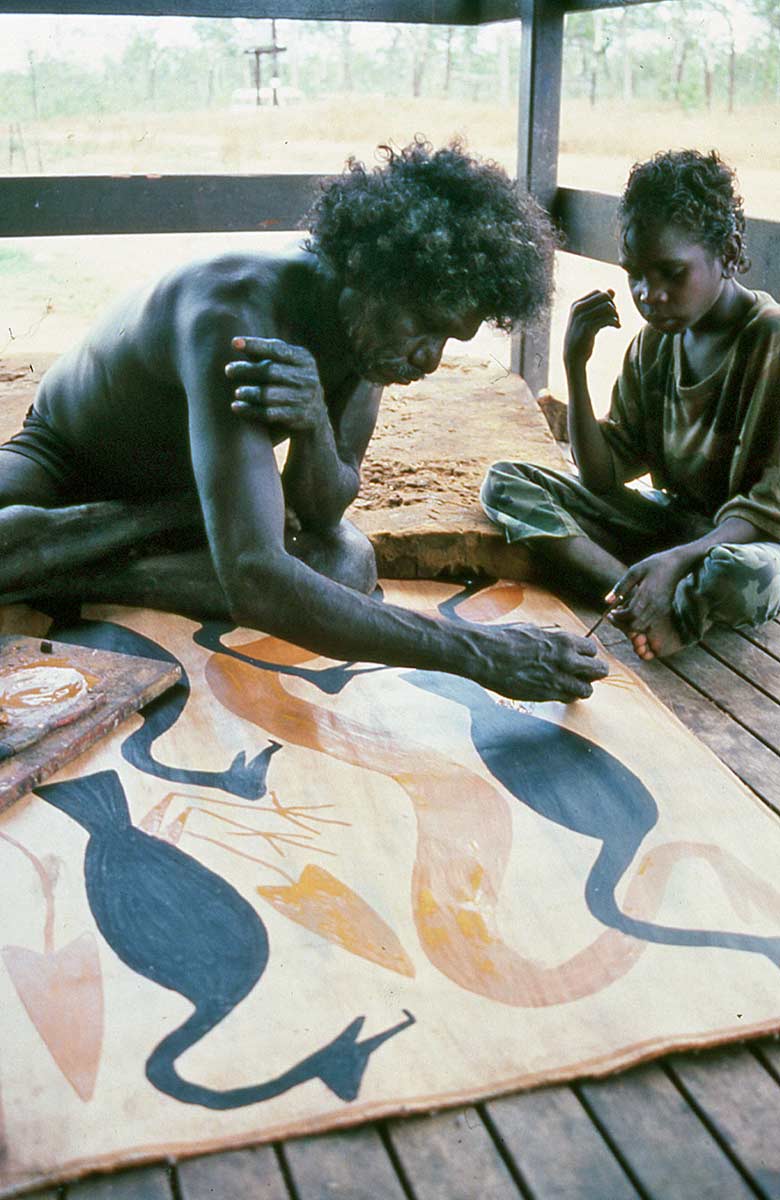

The school of Yirawala developed as a natural outcome of artists sharing camps and outstations with members of their extended families. Such places contain artists’ studios that are out in the open and surrounded by the daily activities of the family – rather than being locked away in secrecy. The open-air studios provide opportunities for artists to work together and to influence each other. They are also where younger family members learn about art.

Marrkolidjban outstation, in the Liverpool River region, played an important role in the history of the development of the artists tutored by Yirawala. It was here that Yirawala and Curly Bardkadubbu, both members of the Born clan, lived and worked in the early 1970s.

Bardkadubbu learnt from Yirawala to paint on bark and, around the same time, Yirawala taught his own sister’s son, Peter Marralwanga, the intricacies of painting patterns of rarrk. Marralwanga in turn taught his nephew Balang Nakurulk who, as a teenager, had been inspired by Yirawala.

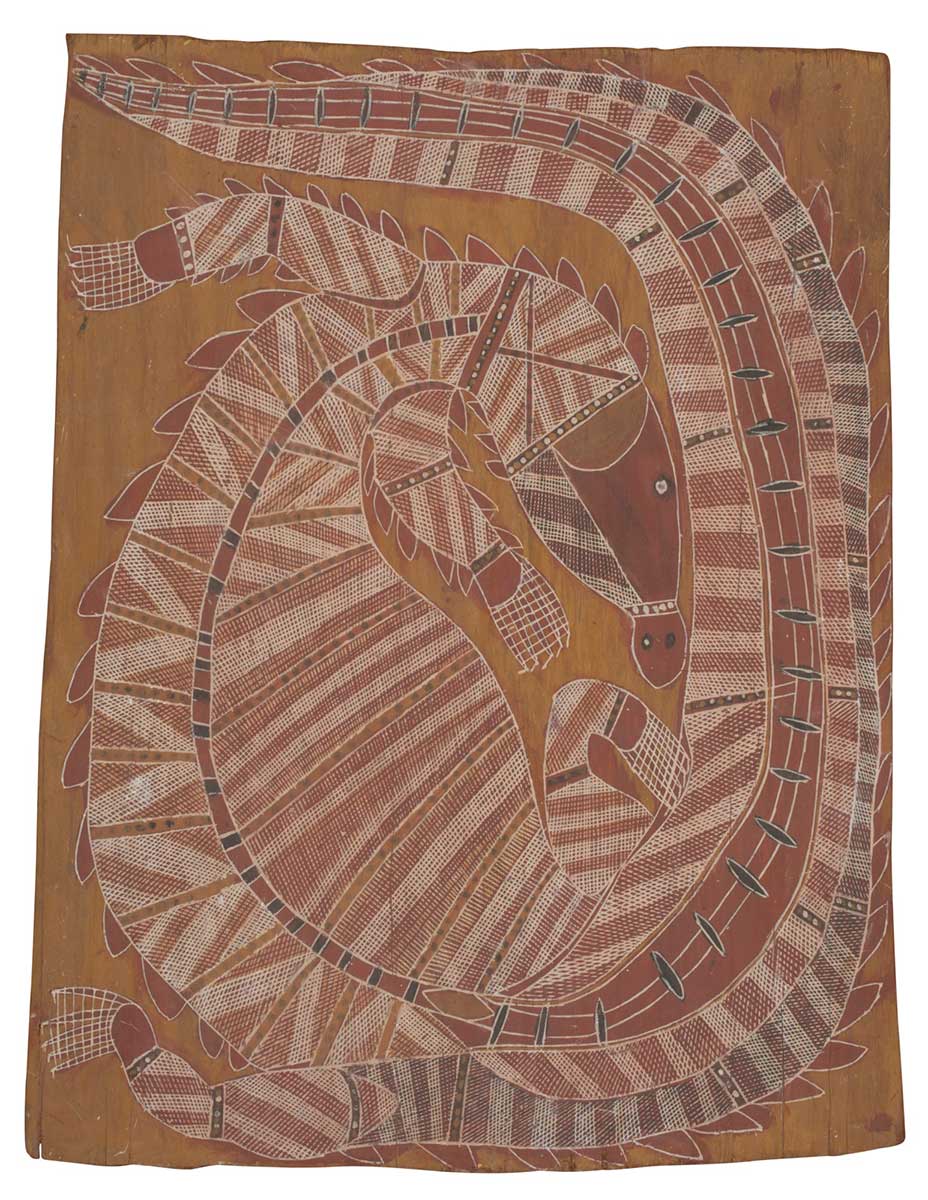

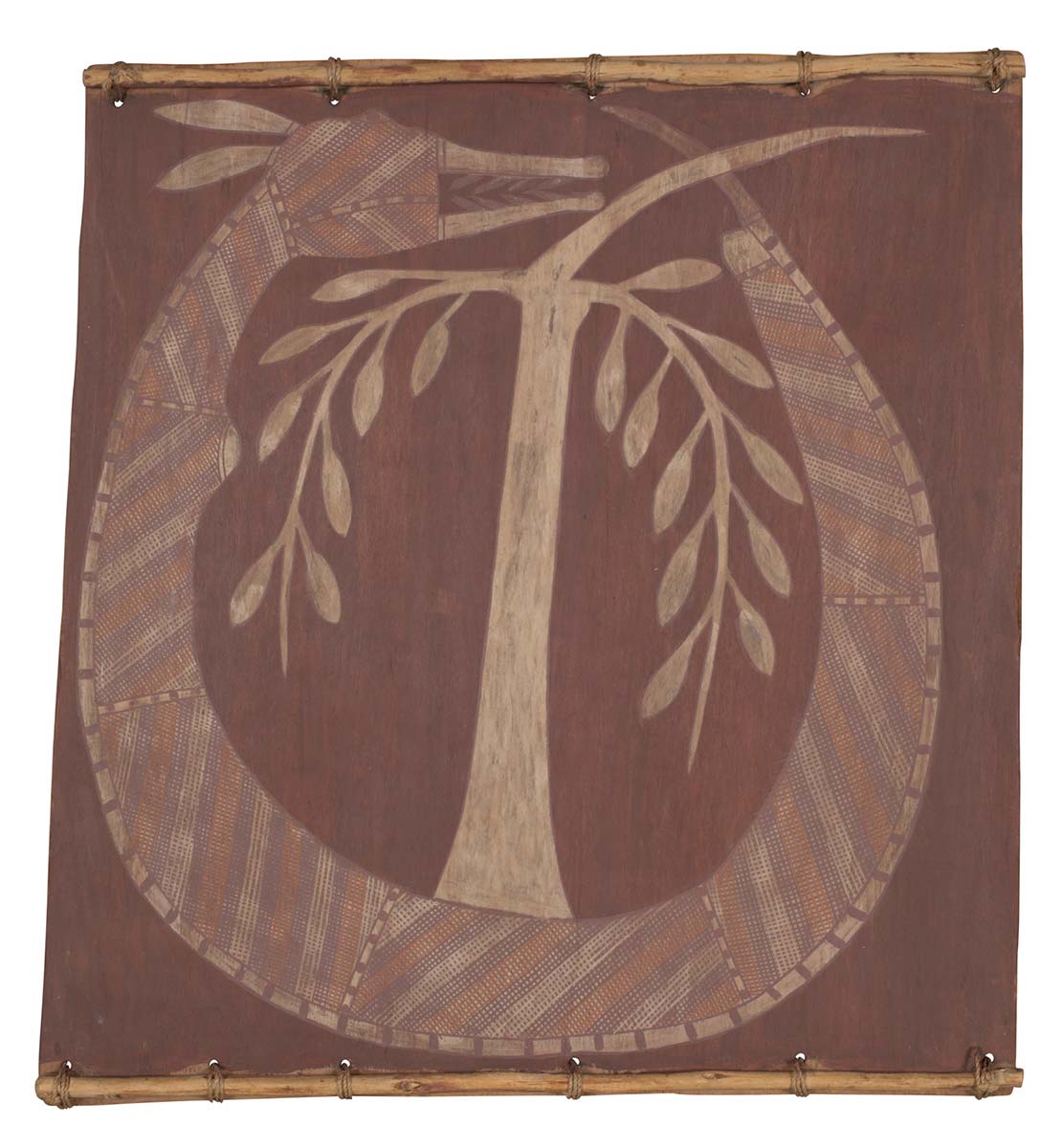

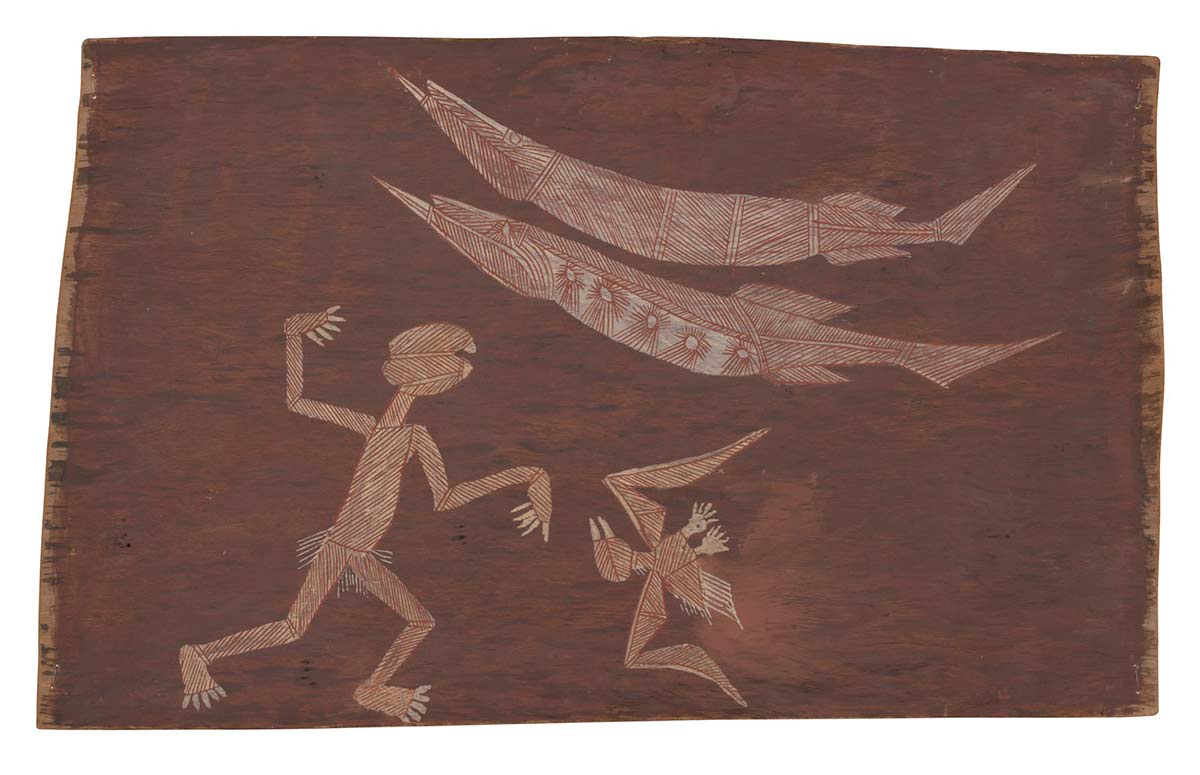

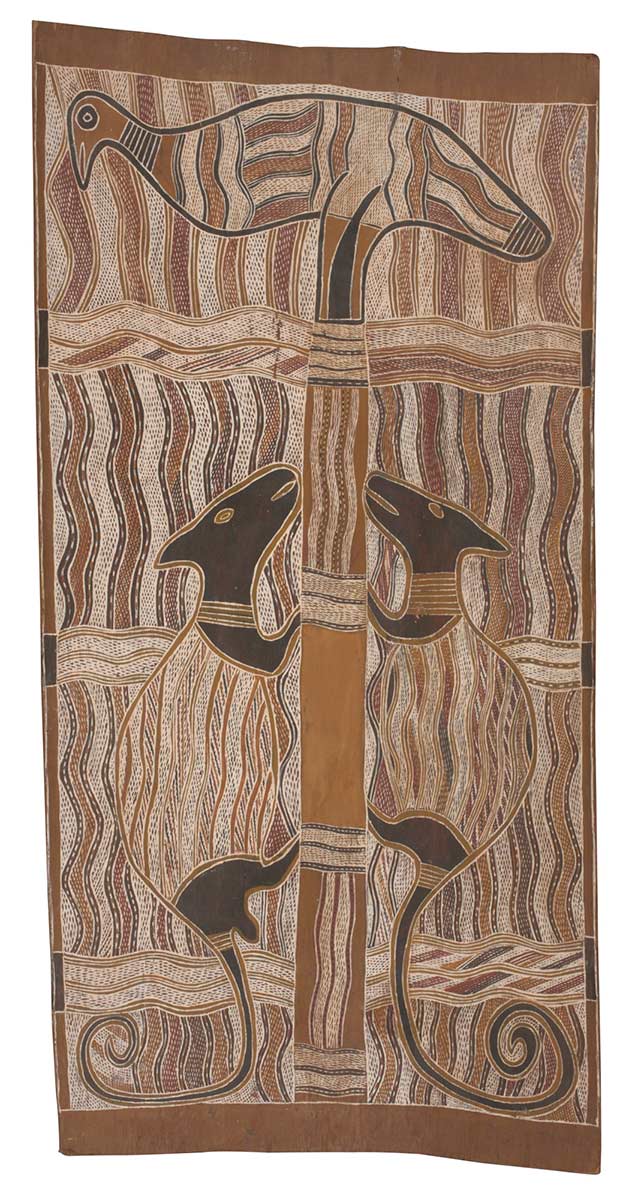

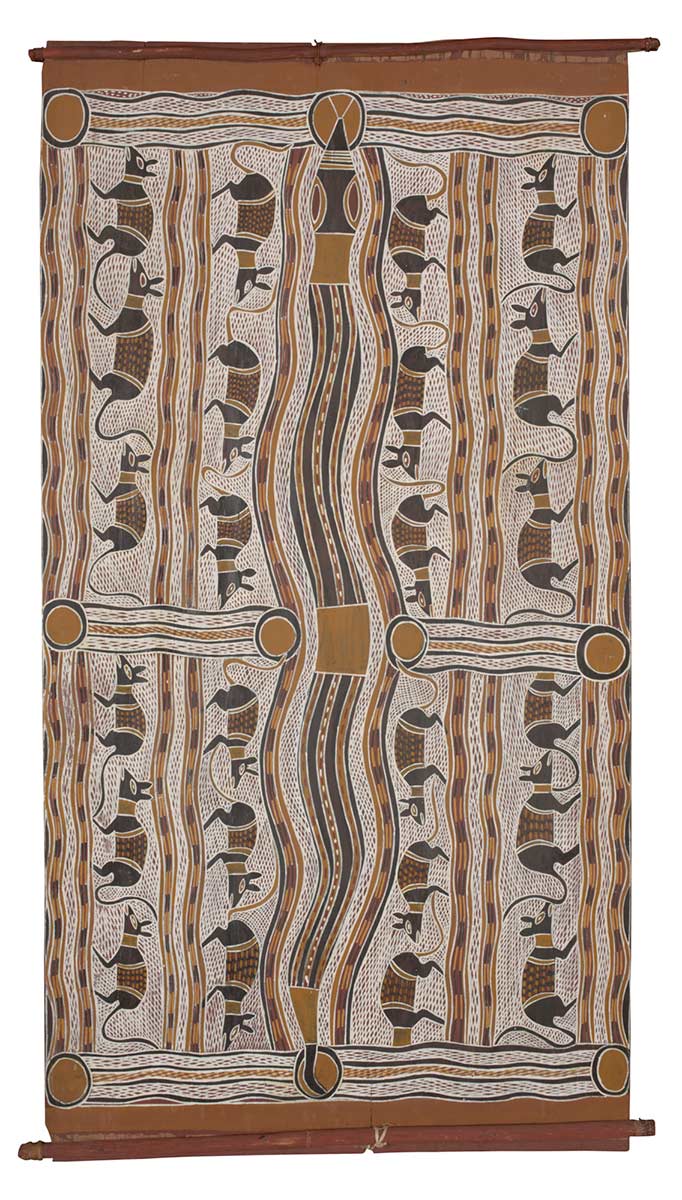

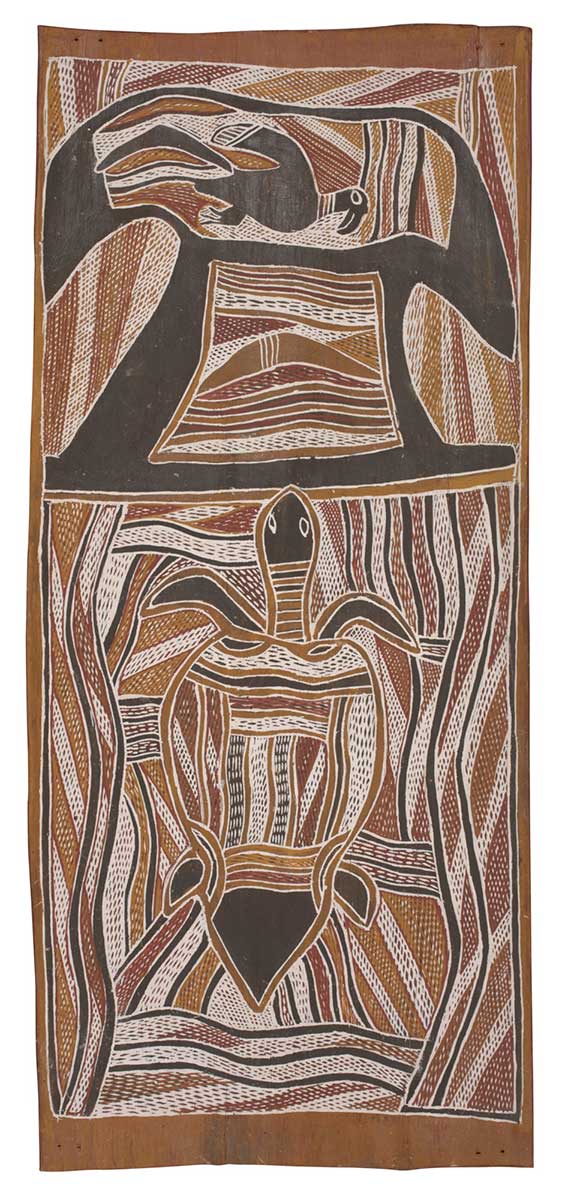

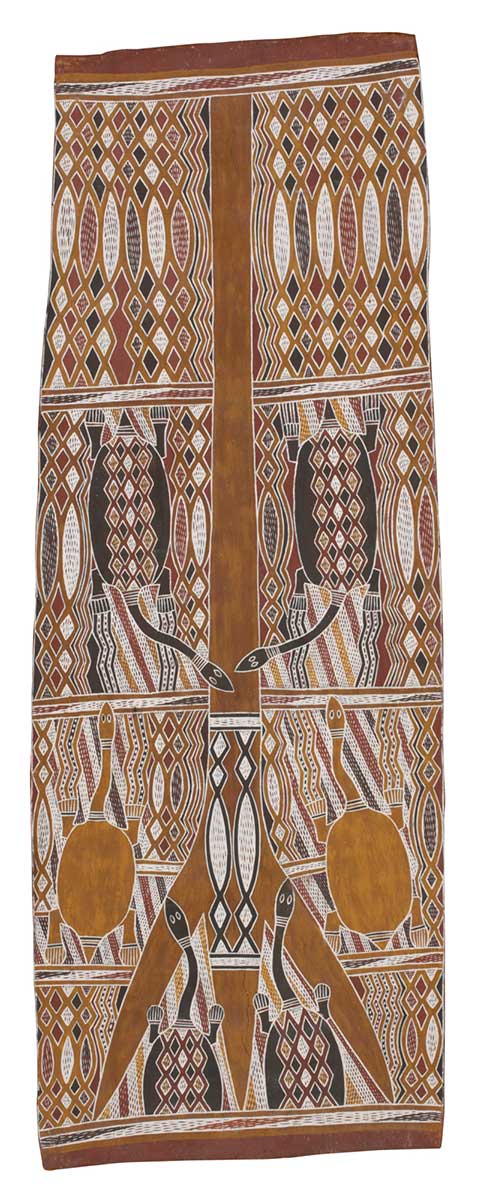

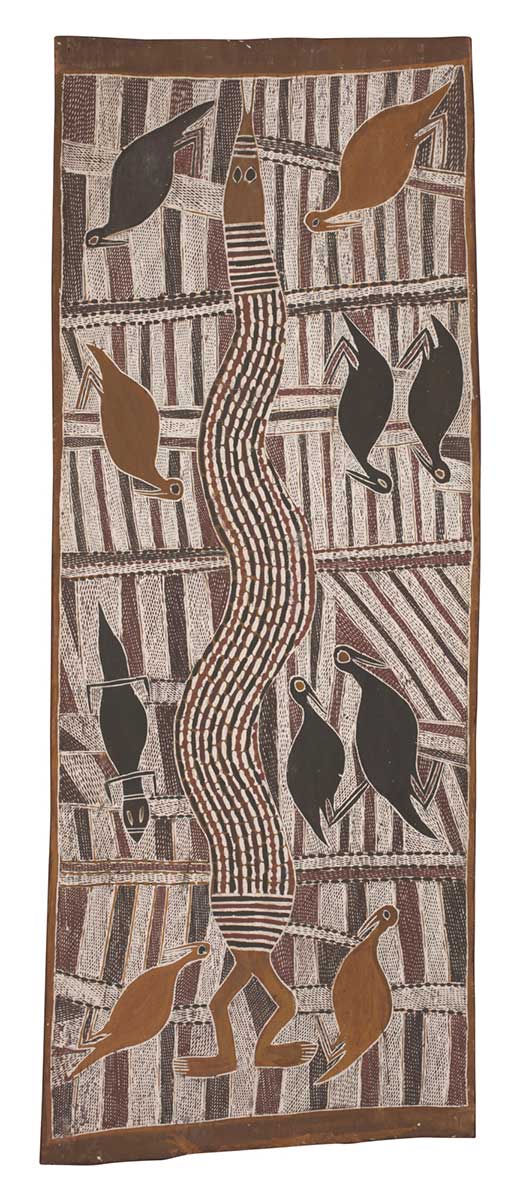

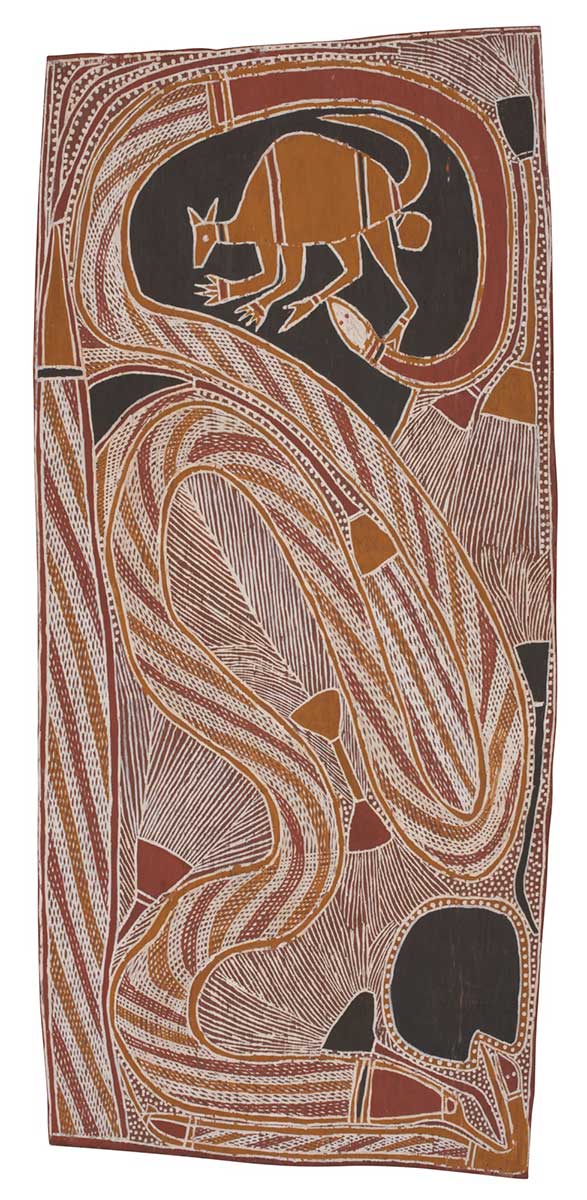

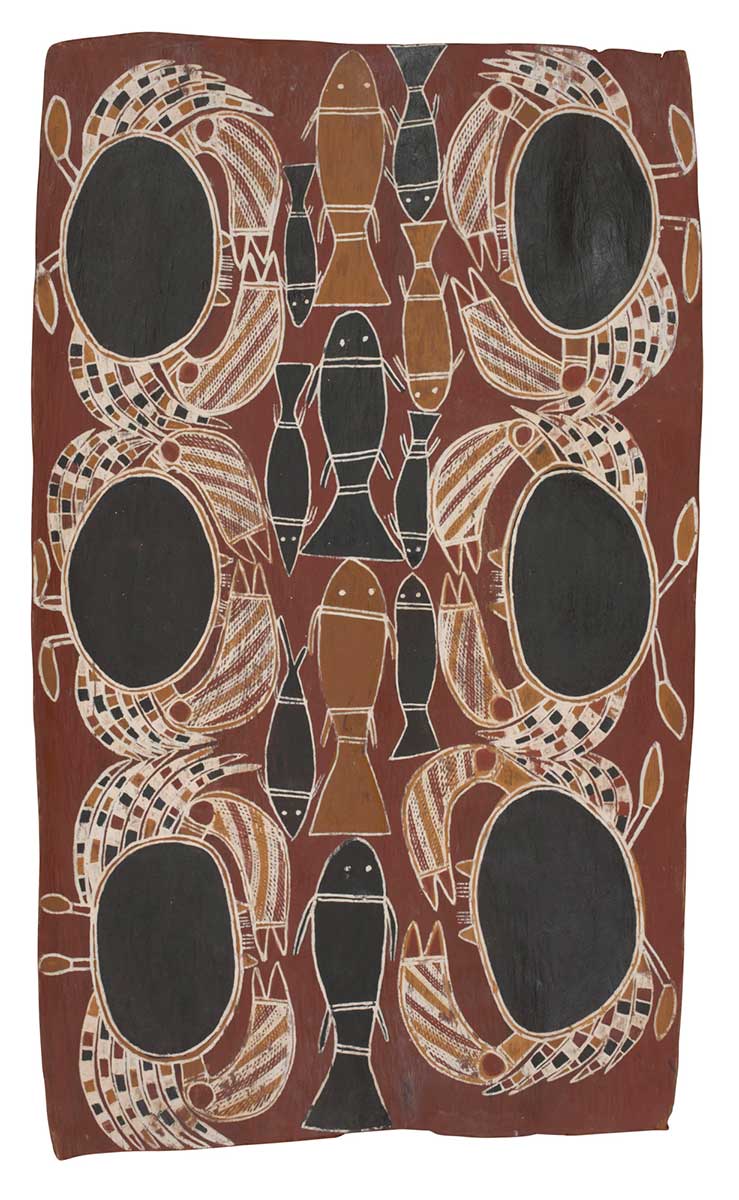

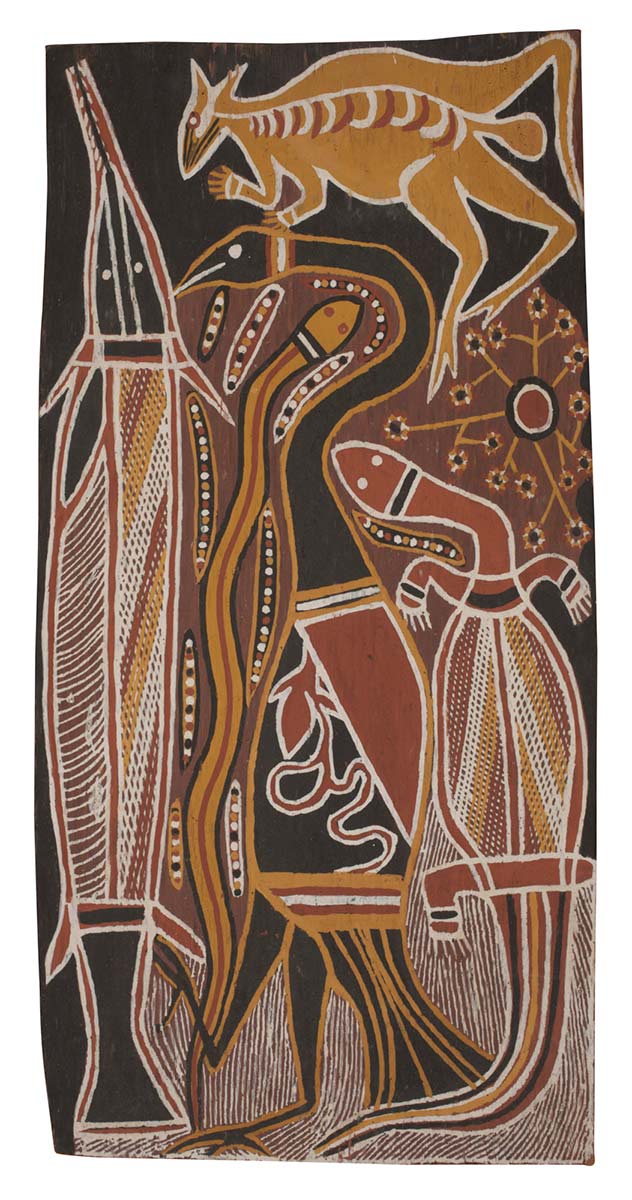

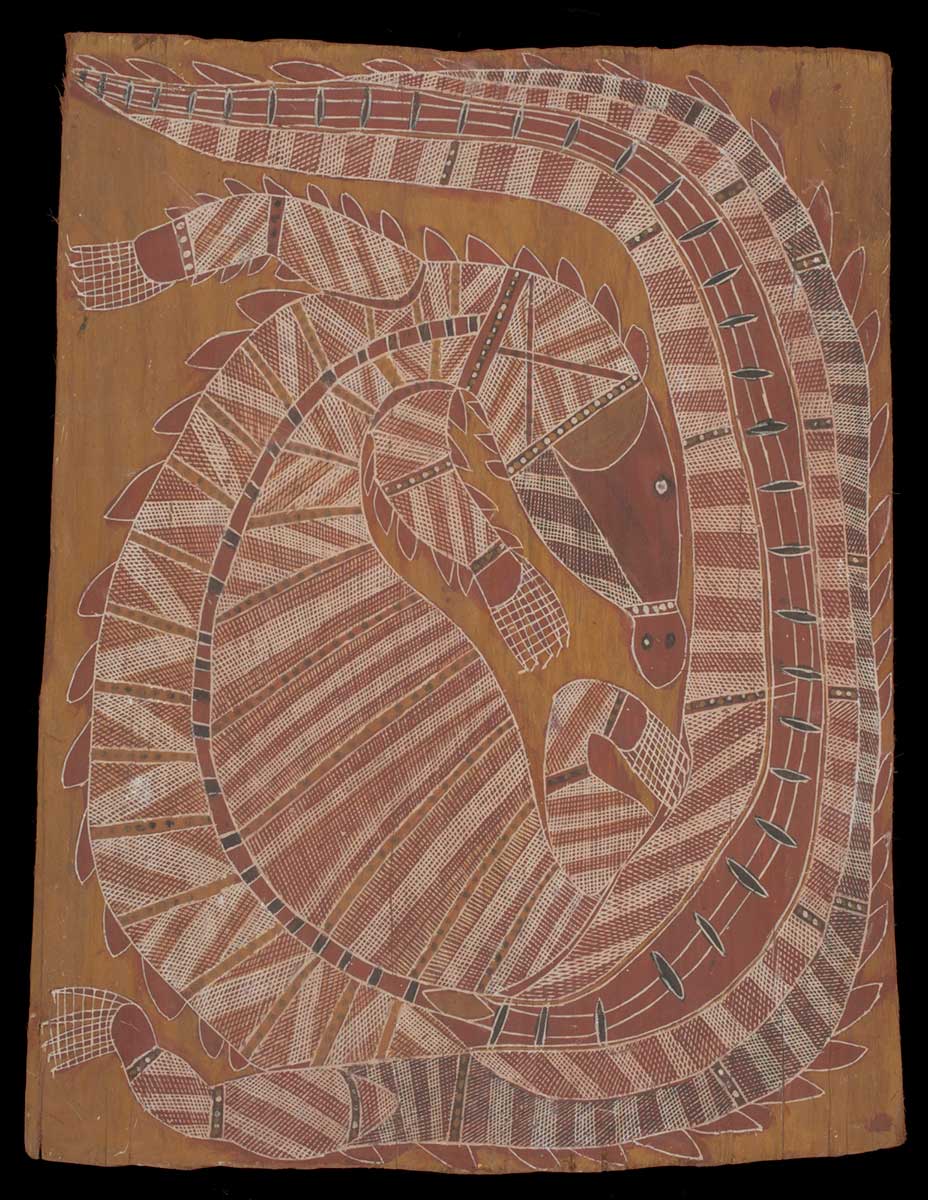

Note the similarities in these artists’ renditions of Ngalyod the Rainbow Serpent and Namanjwarre the Estuarine Crocodile. In each case the sheer power of the creatures is expressed in the drawing of the figures as coiled springs, ready to snap and unleash their herculean powers.

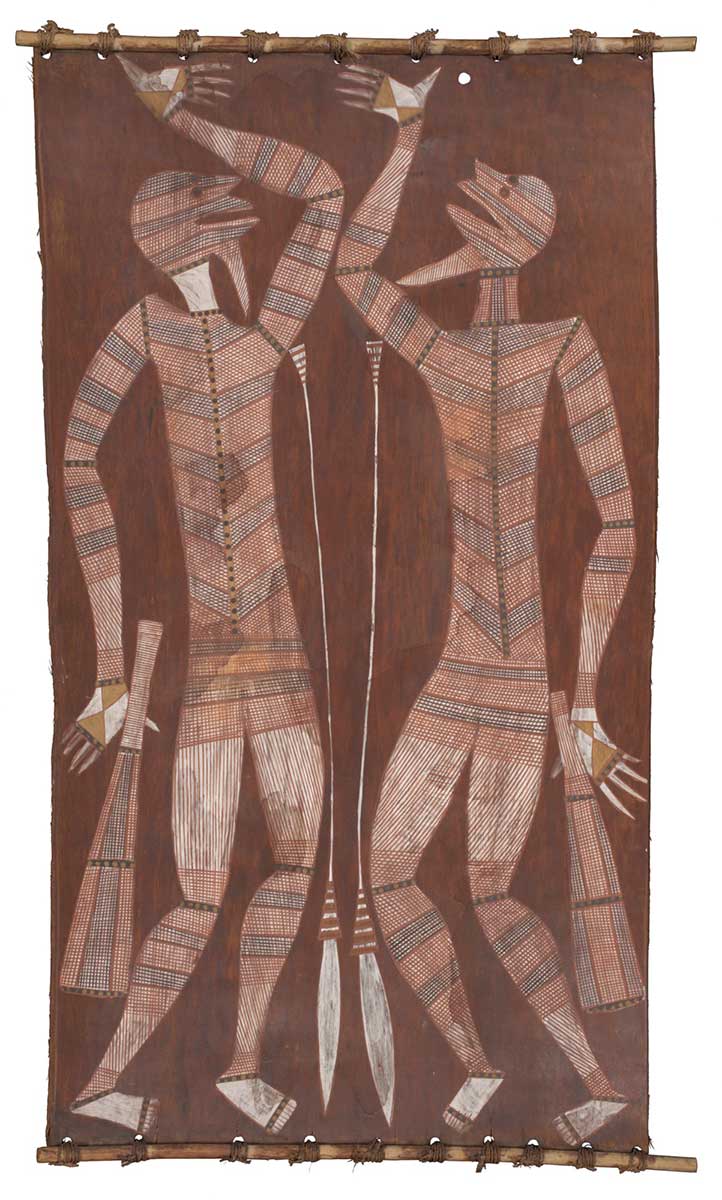

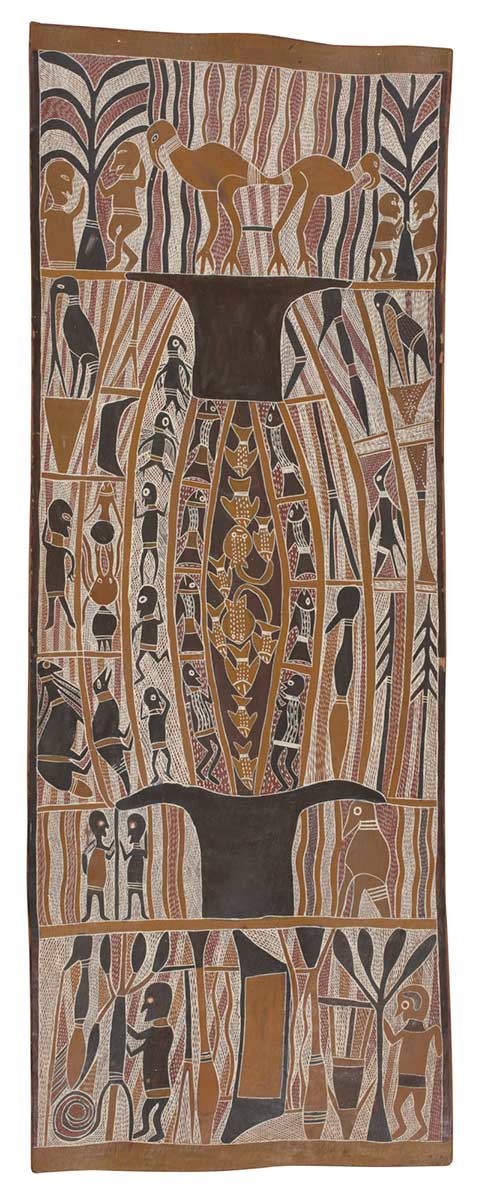

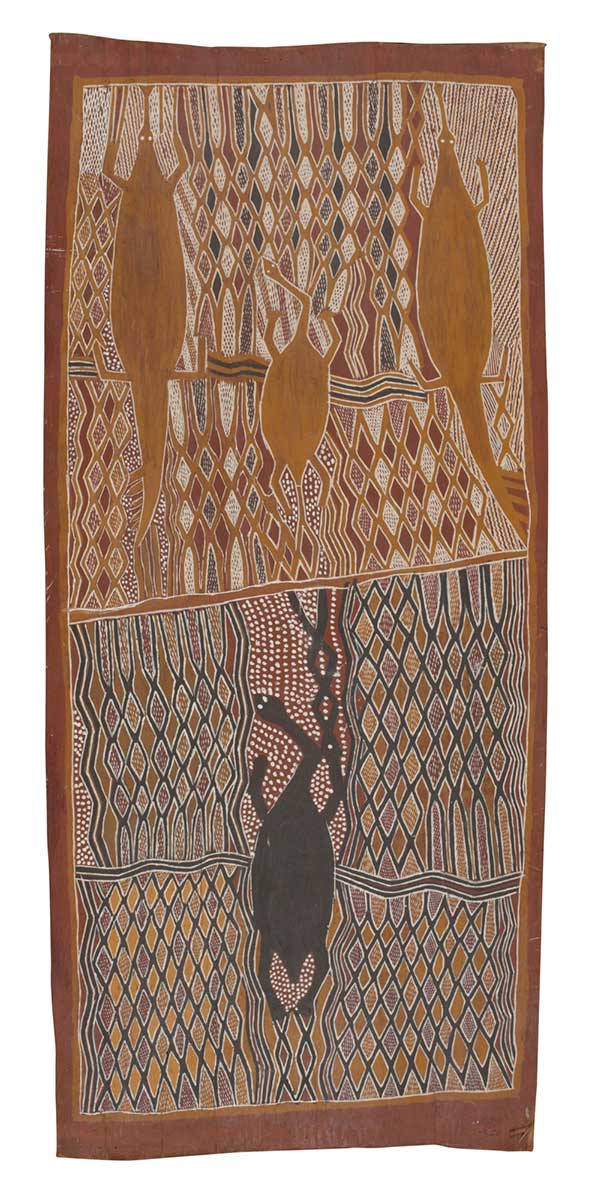

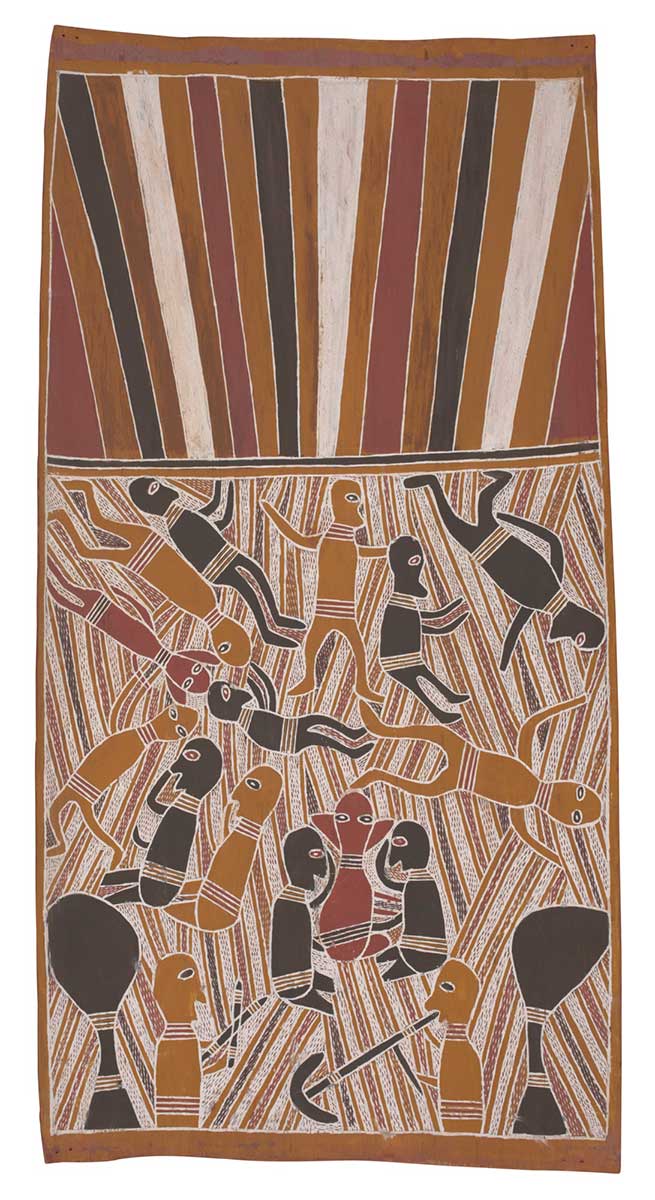

Figures in the landscape is a genre of painting in the western European tradition that seeks to express the connection between people and their environment, and its influence on a person’s identity. The ancestral figures in bark paintings not only inhabit the country, they also created it; they metamorphosed into its features and they deposited their ancestral forces within the earth itself.

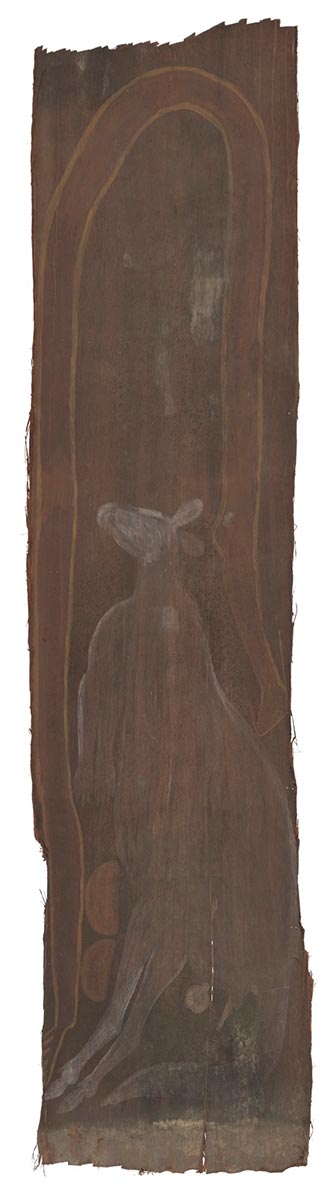

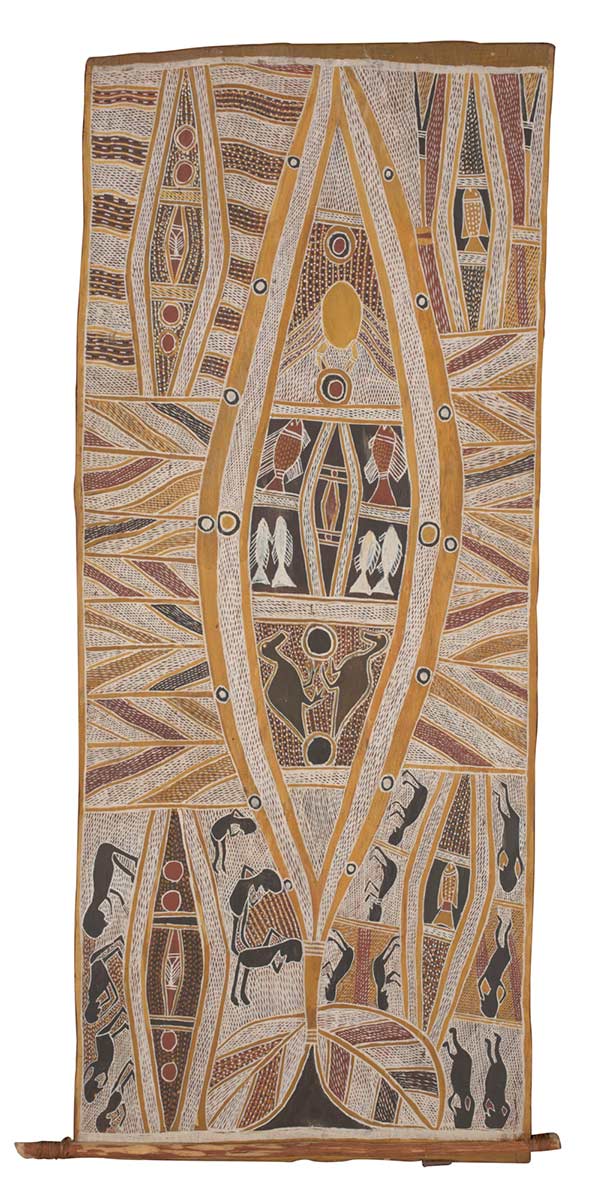

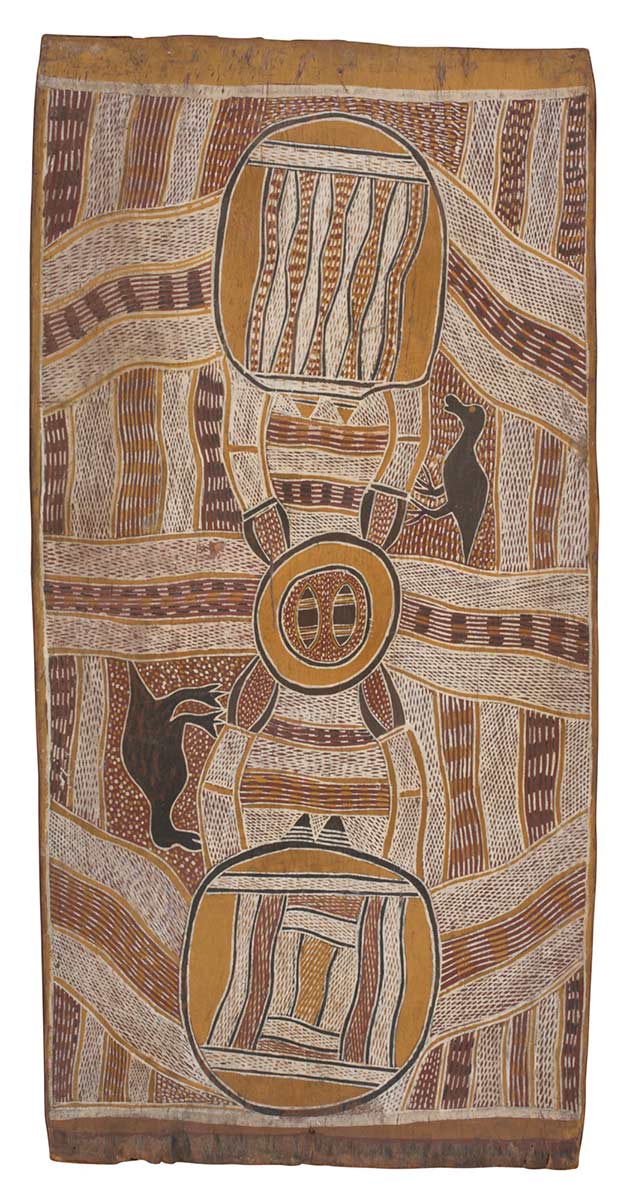

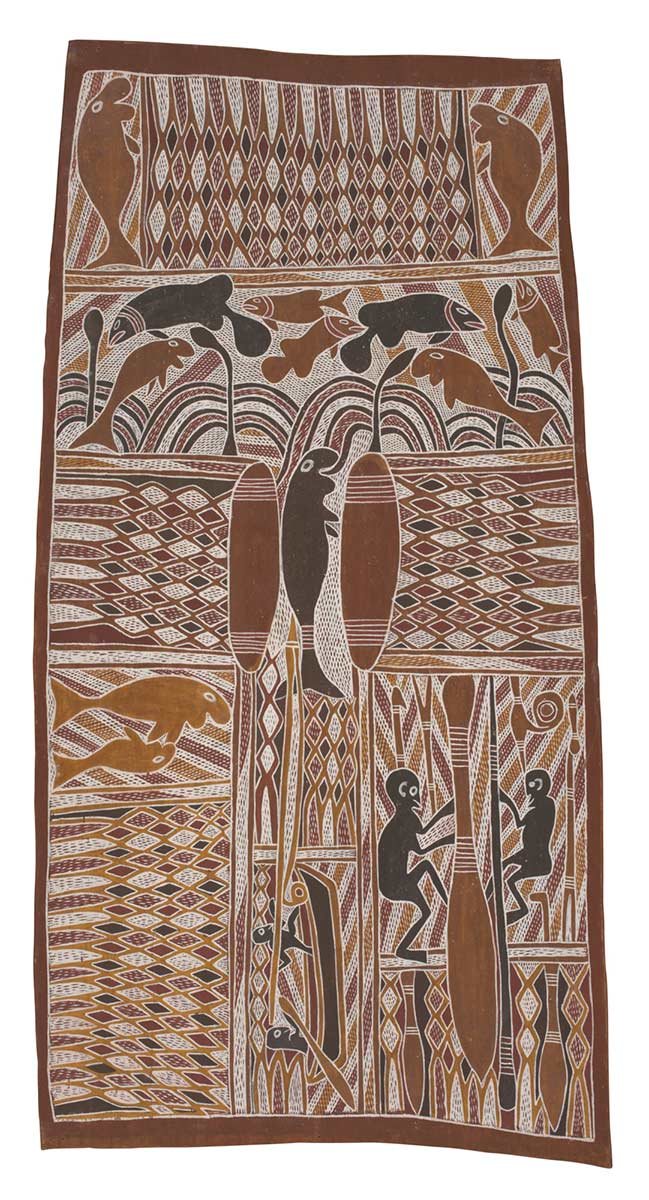

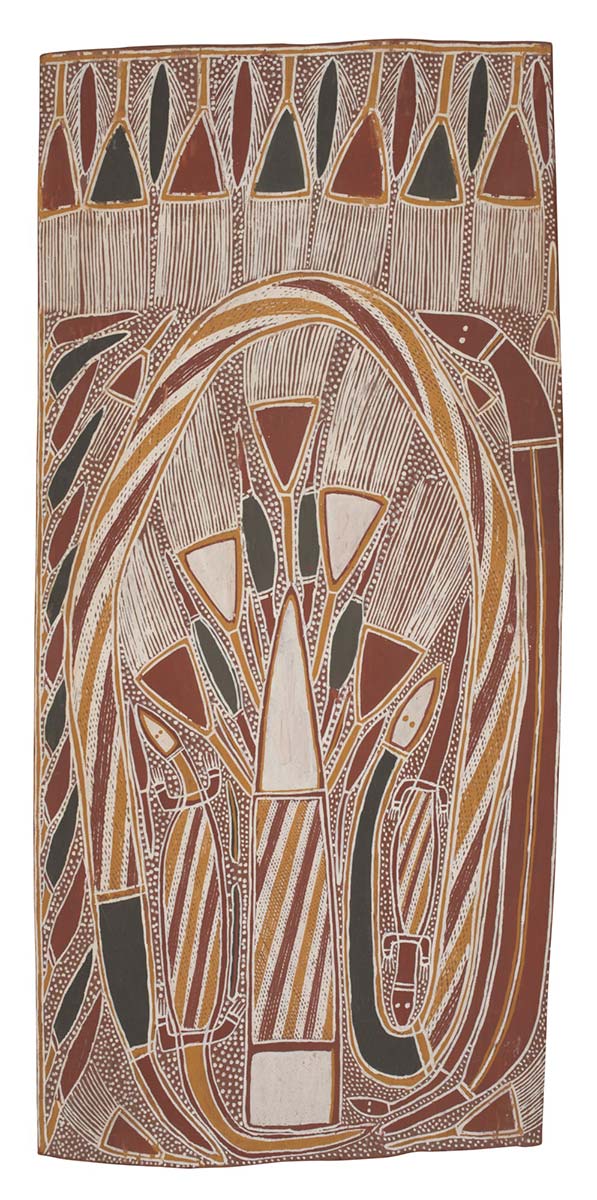

Chief among these creator beings is the Rainbow Serpent, commonly known as Ngalyod, who may appear in several guises. Ngalyod creates sacred sites by burrowing its way through the earth to emerge on the surface, where it encircles and swallows spirit beings. These may be taken into the ground or regurgitated as features of the landscape.

The Rainbow Serpent is sometimes drawn as a composite of several creatures, with the head of a crocodile or kangaroo, an emu’s crop and the tail of a fish. Ngalyod the Rainbow Serpent by Bardayal Nadjamerrek depicts Ngalyod beneath the surface of a billabong. Images of ‘seated’ beings indicate they are giving birth to particular sites.

The artists in this section all lived in and around the township of Oenpelli (Gunbalanya) in the 1960s and 1970s, when most of these paintings were made.

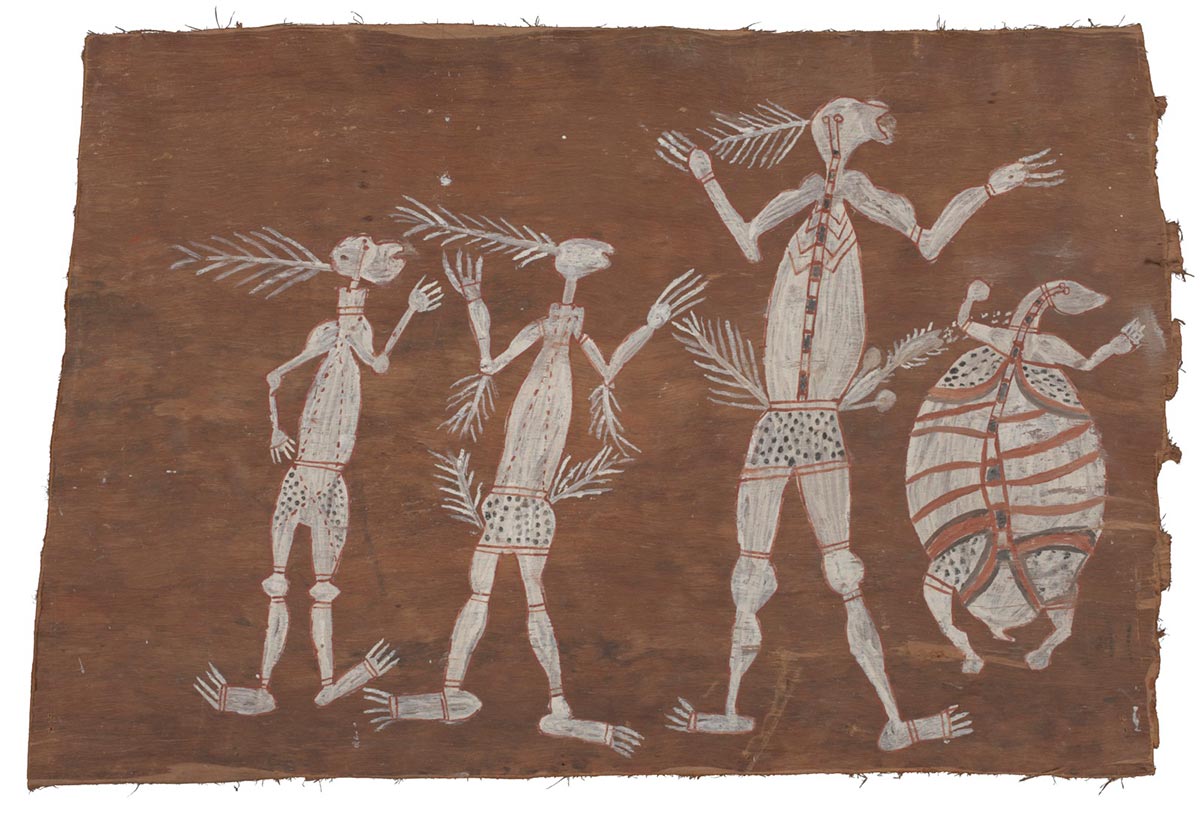

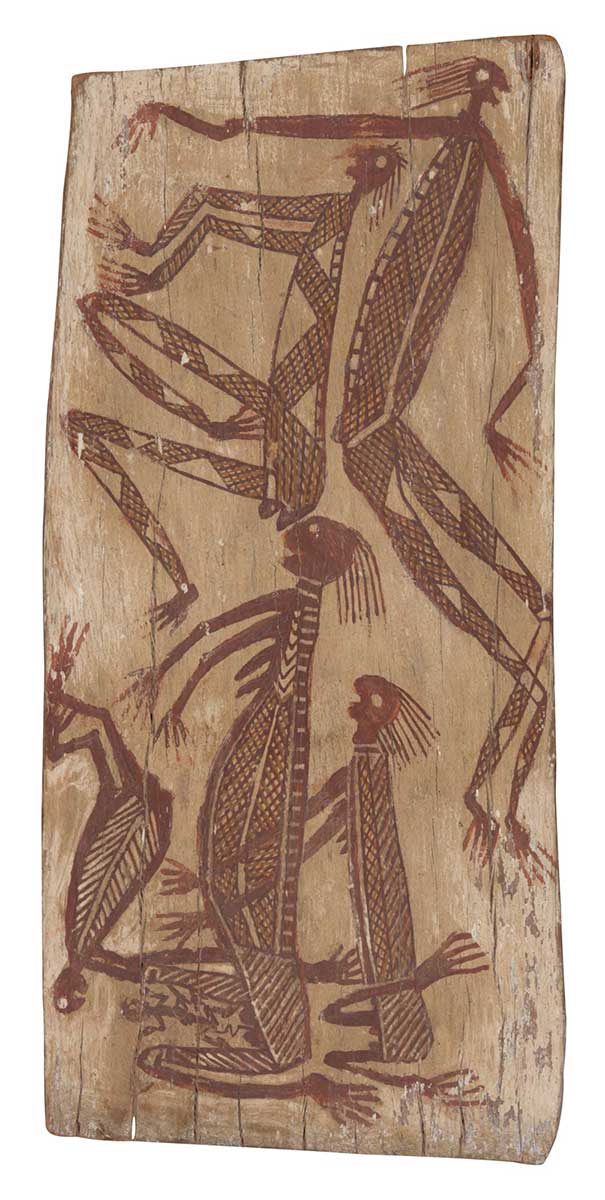

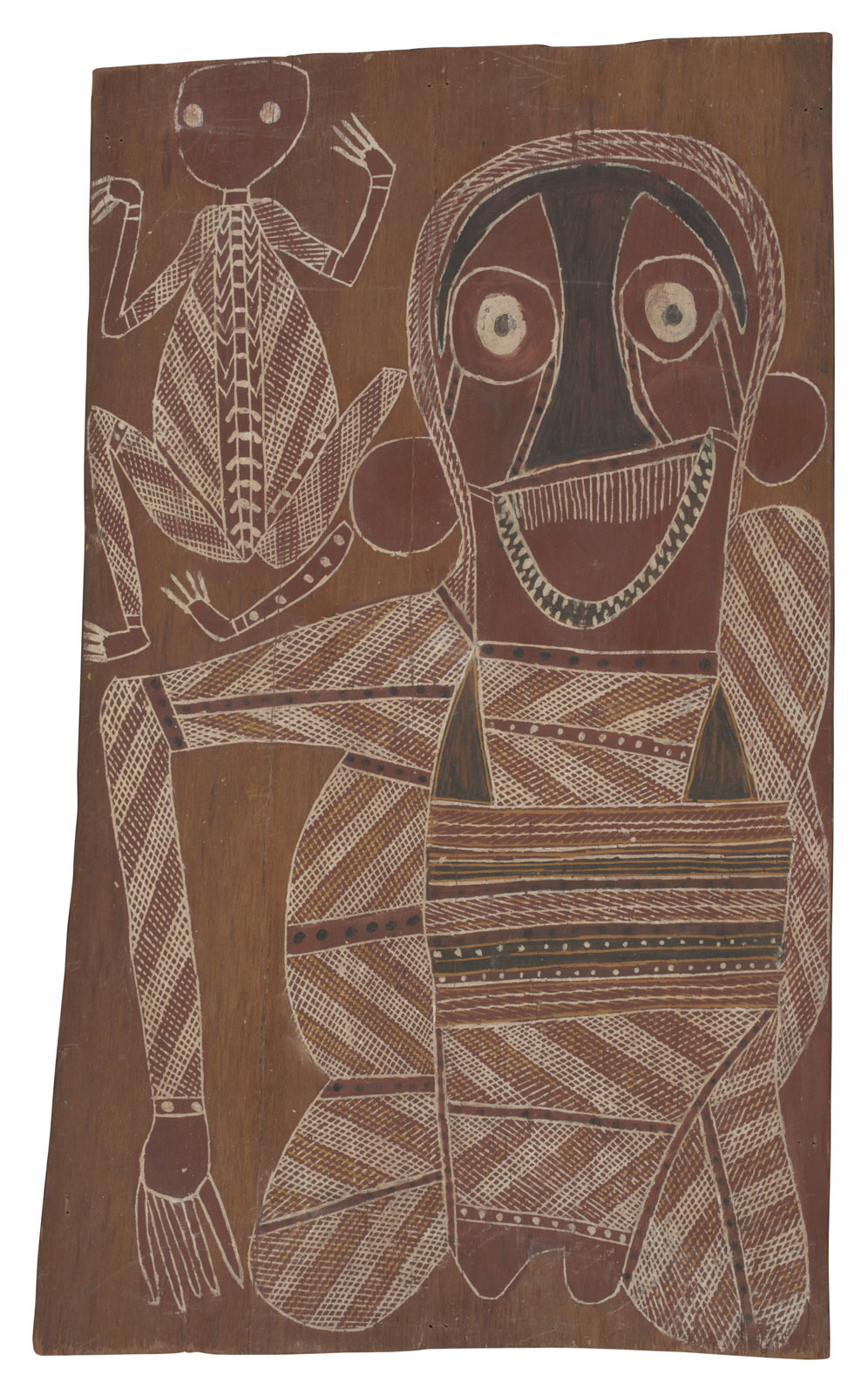

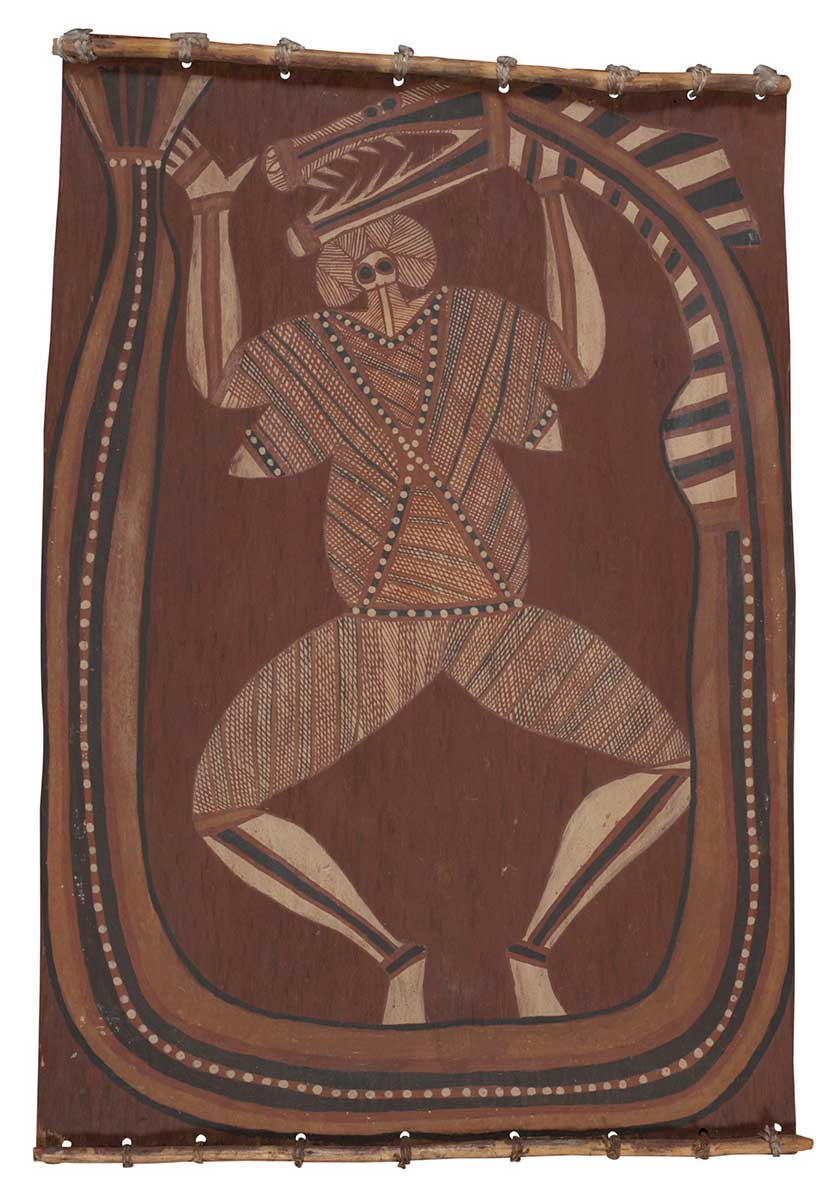

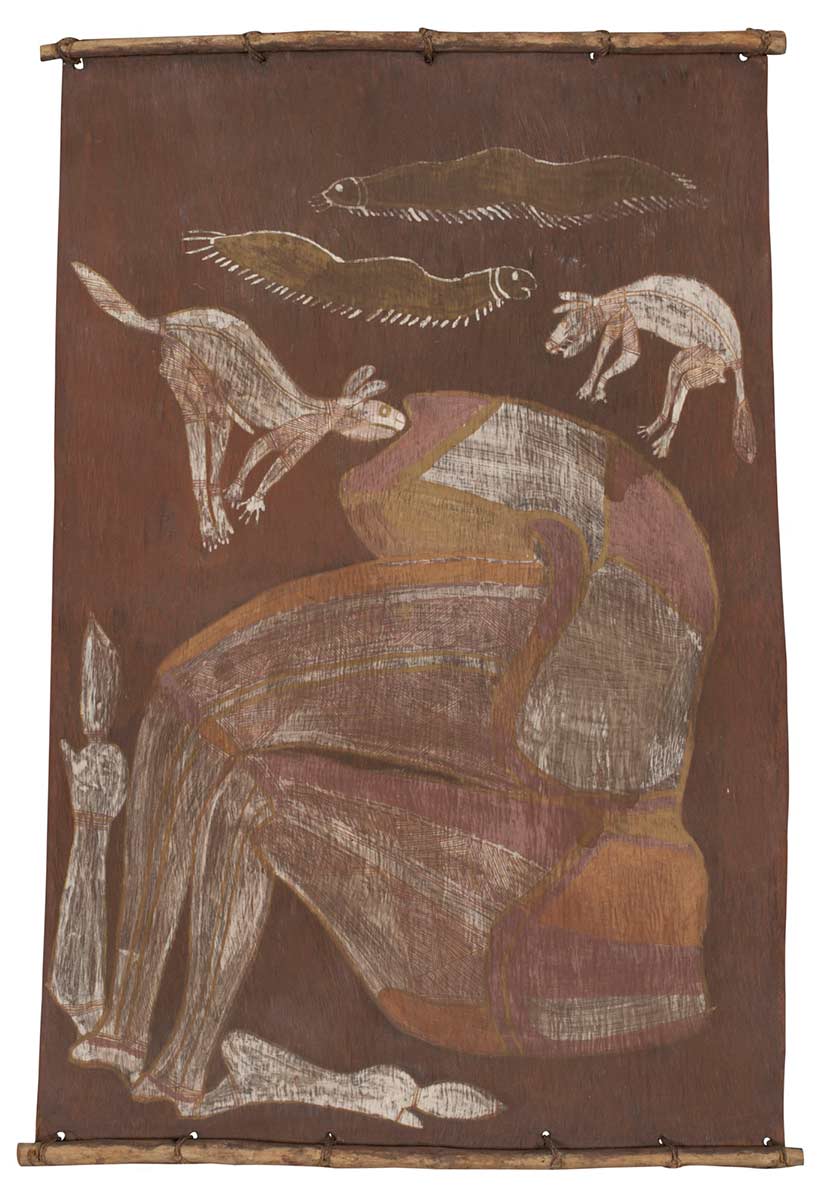

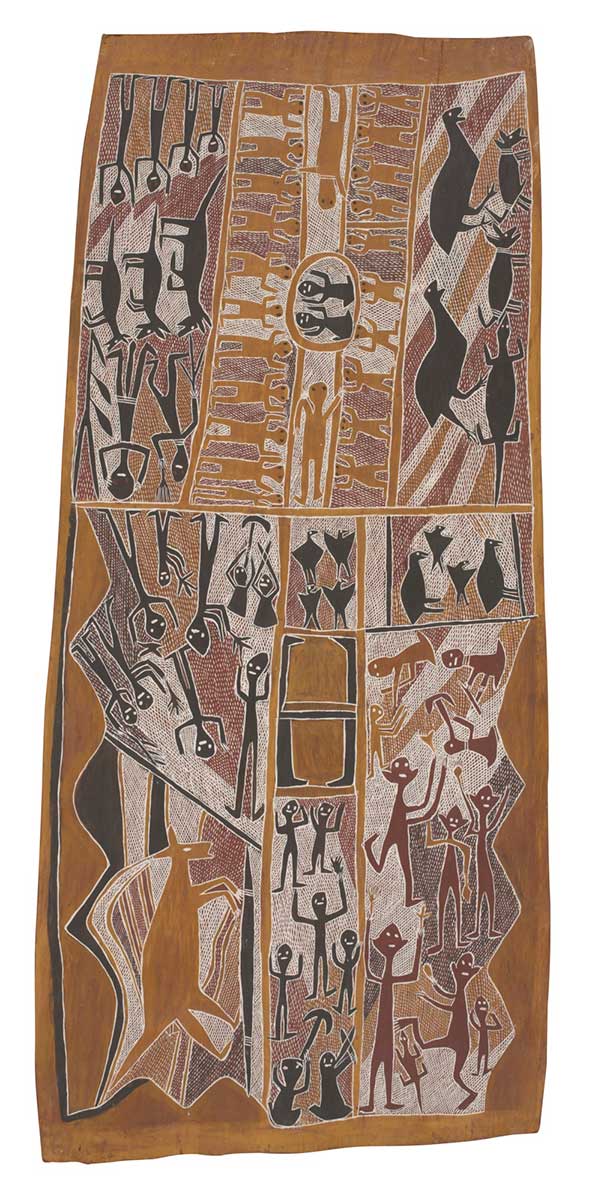

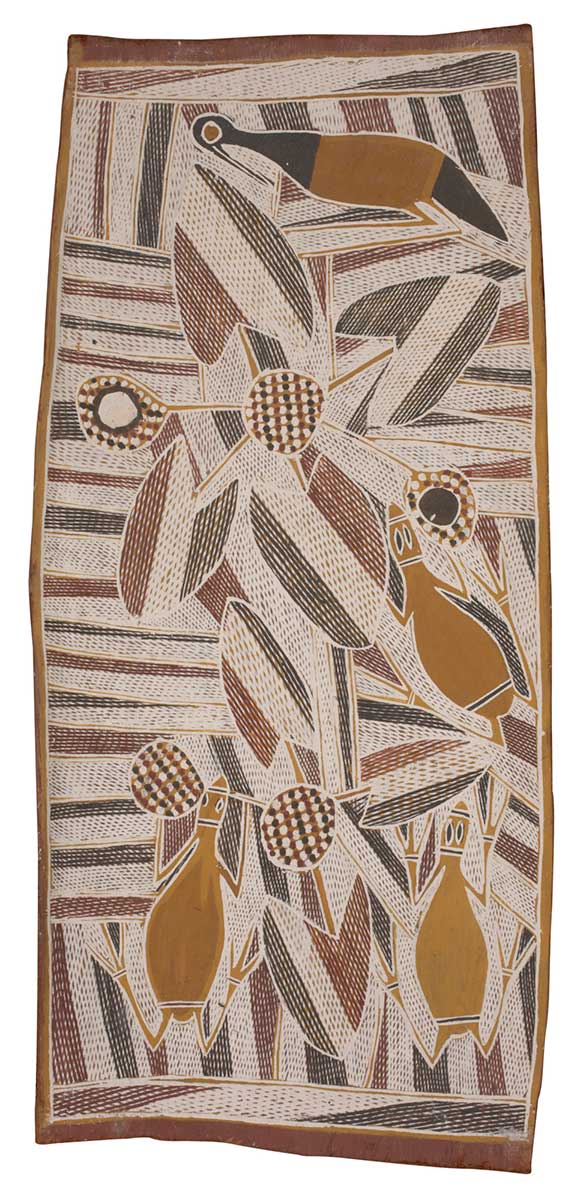

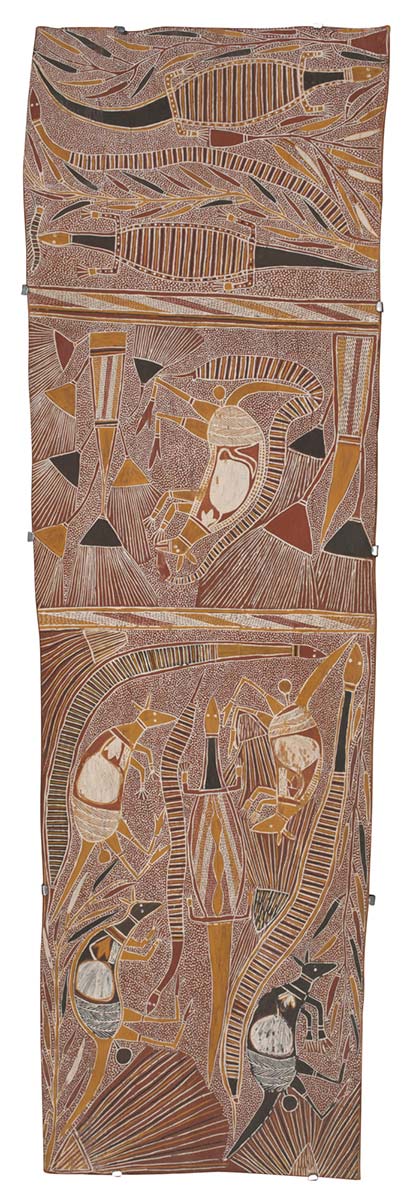

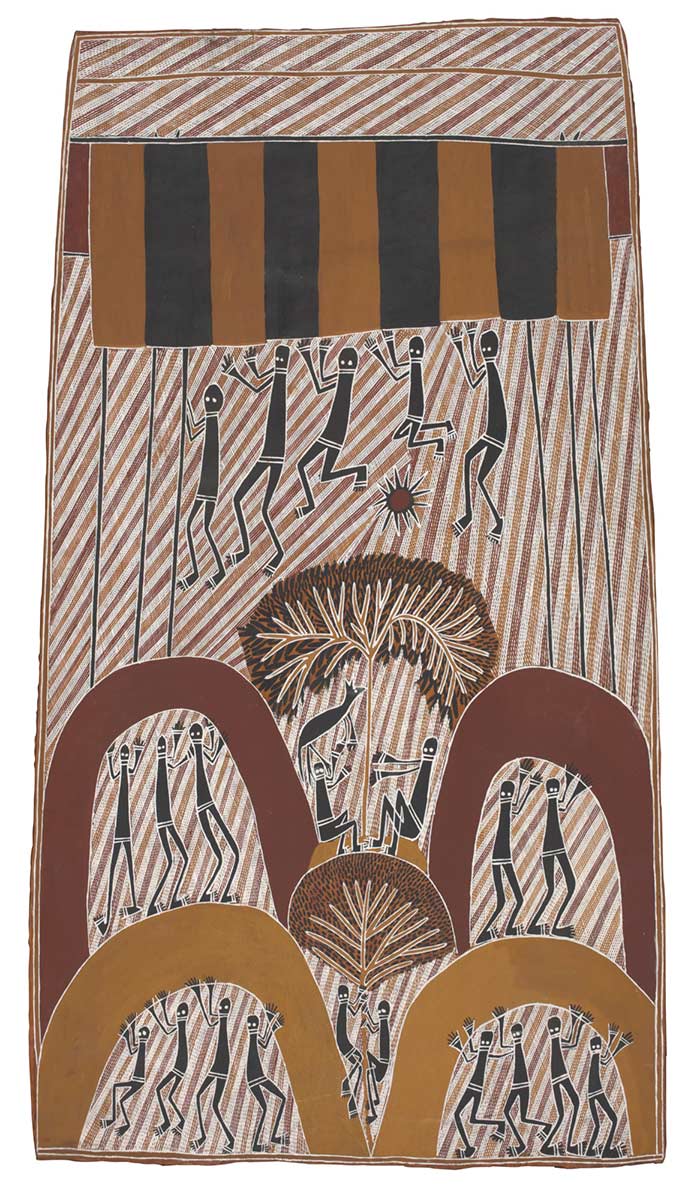

Dynamic figures is a term applied to a style of rock painting in western Arnhem Land that dates back at least 15,000 years. These figures are drawn as though caught in the act of movement, whether running, throwing a spear or dancing. A number of artists in this exhibition, including Najombolmi, Wally Mandarrk and Bardayal Nadjamerrek, also painted on rock.

The figures in these paintings are usually referred to as mimih. These are not ancestral or creator beings but spirits who inhabit the rocky escarpment. Mimih are credited with teaching the Bininj people the arts of living: how to hunt, cook, dance, sing and paint.

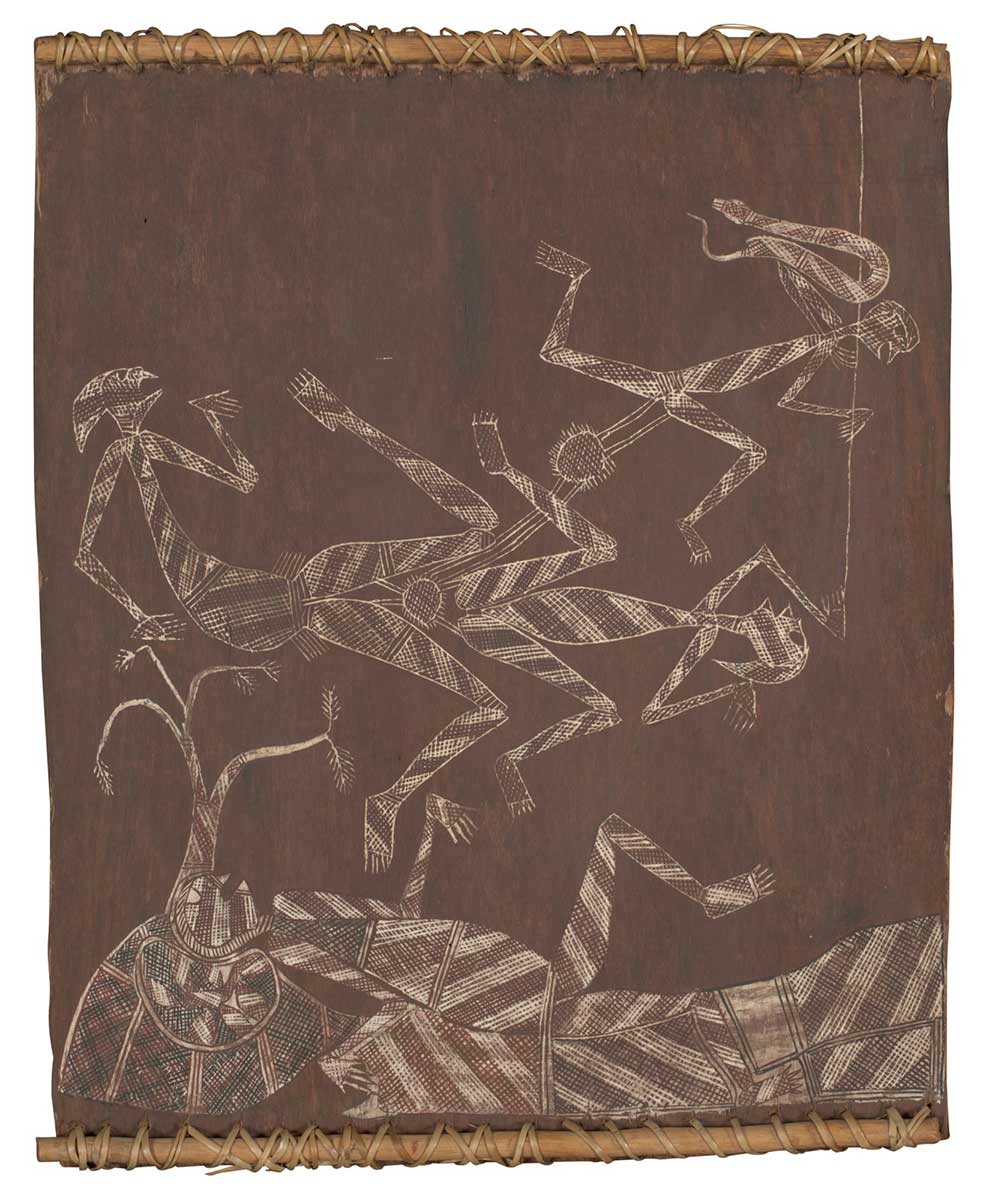

A type of painting that appears in the rock art of the region concerns sorcery. Such paintings were often commissioned to bring harm on a person who had wronged another, often for sexual infidelity. In the latter case, images of the culprits are drawn with distended and multiple limbs in awkward postures and occasionally with stingray barbs inserted into the joints and flesh to inflict pain.

The Nganjmirra family is one of the great artistic dynasties of Arnhem Land. Bobby Barrdjaray Nganjmirra was the senior artist of the group in the modern period. The family’s traditional lands lie to the east of Gunbalanya and are the focus of their paintings. Among the most important sites to the Nganjmirra family is Malworn, created by the Yawkyawk Sisters, Likkanaya and Marrayka; the latter is depicted in Barrdjaray’s painting of the same name.

The creation story of this site has similarities to that of the Wägilak Sisters in central Arnhem Land. Nimbuwah Rock is another important place to which the Nganjmirra family has custodial or managerial rights, as opposed to ownership, as it belongs to the opposite moiety, the Duwa.

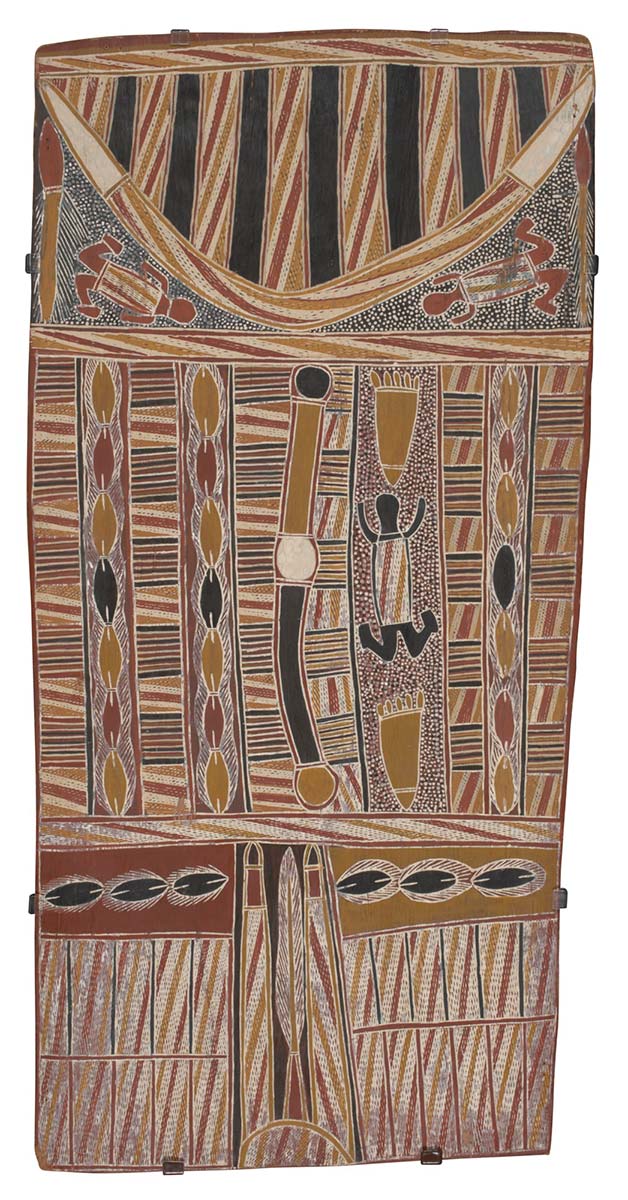

Mural painting is another form of painting on bark, and stems from the practice of artists drawing or painting on the inside walls of their family bark huts or shelters.

There are two main types of bark shelter in Arnhem Land: one with straight walls, and the other made of walls curved over a horizontal beam (see George Milpurrurru’s Galawu (Stringybark House). Both types are built using large sheets of flattened bark. Painting on bark shelter walls predominated until the early 20th century, when collectors created a demand for more portable bark paintings.

Wally Mandarrk’s Borlung and Kangaroo was a mural made specifically for Mandarrk’s family in a camp at Mankorlod that was later abandoned. It was discovered by a Maningrida art centre manager, Dan Gillespie, in 1973. Two Frogs and a Baby Brolga was also cut from the wall of such a shelter.

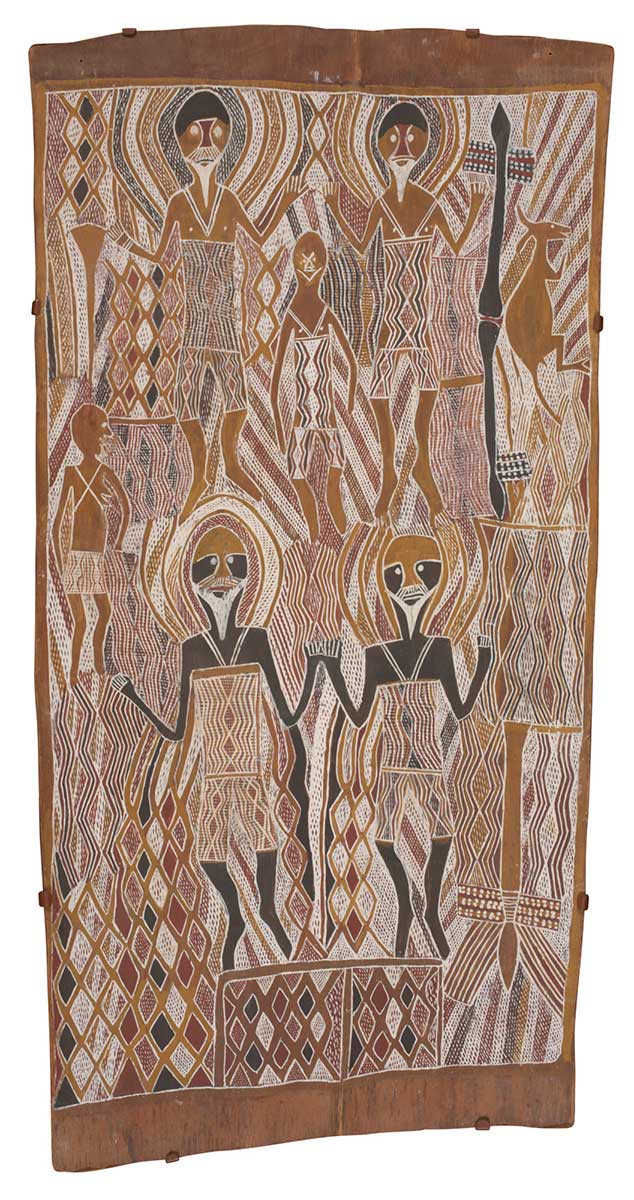

The Yolŋu-speaking artists of the region are renowned for their engagement with the wider community.

In the early 1960s many of the artists shown here collaborated in painting the monumental Yirrkala Church Panels, which were placed either side of the altar of the local mission church as an act of affirmation of traditional culture.

They also painted the Bark Petitions that were presented to Parliament as deeds of title to their land in the first Land Rights case 50 years ago. Narritjin Maymuru was one of the chief protagonists in both events and is the focus of this section.

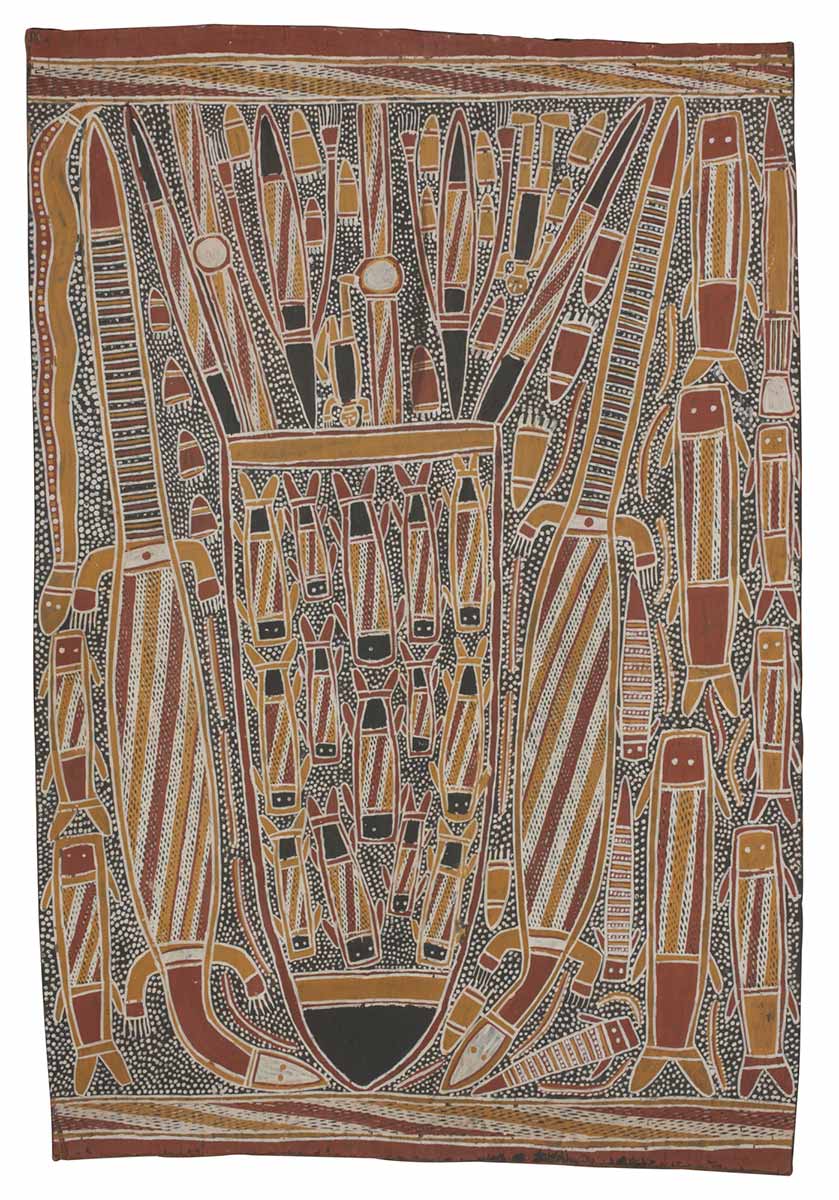

Narritjin Maymuru was a ceremonial leader of the Yirritja moiety and Maŋgalili clan, and a highly influential artist. The main theme in his paintings concerns two ancestral women, the Nyapililŋu (also known as Wurrathithi), who mourn the death of their brother, Guwak the Koel Cuckoo, at the salt lake of Djarrakpi on Cape Shield.

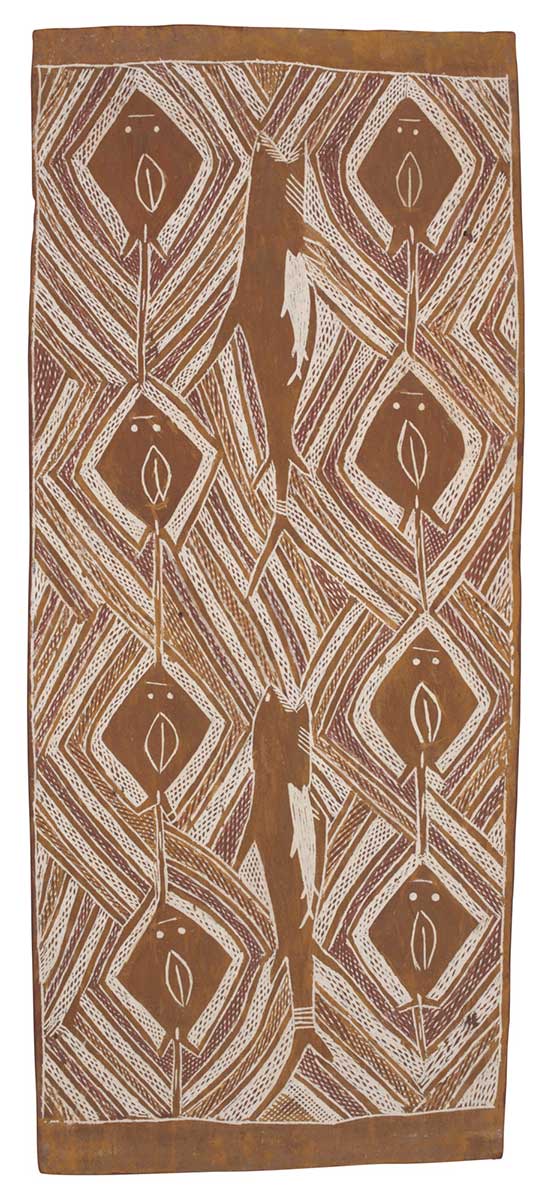

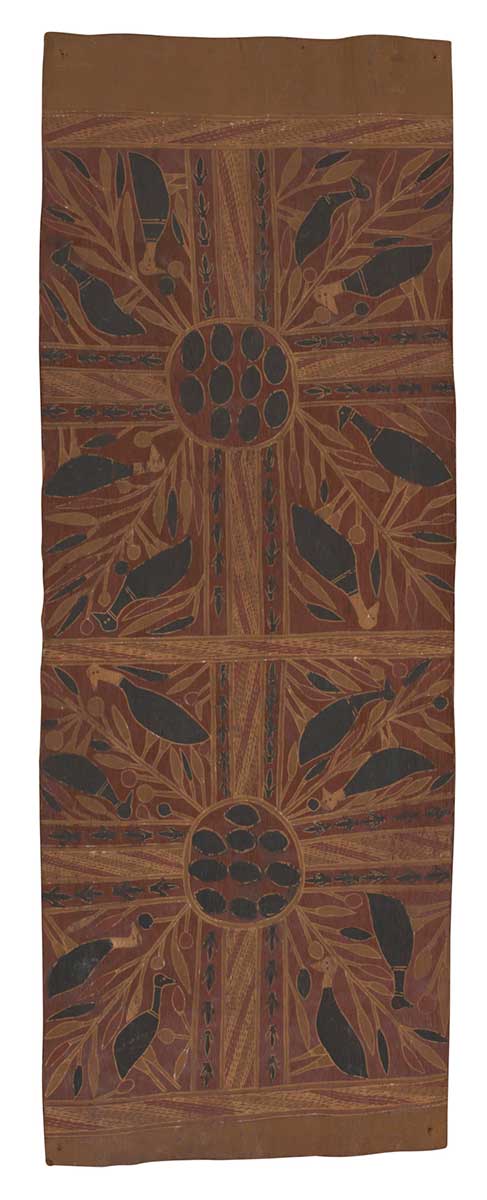

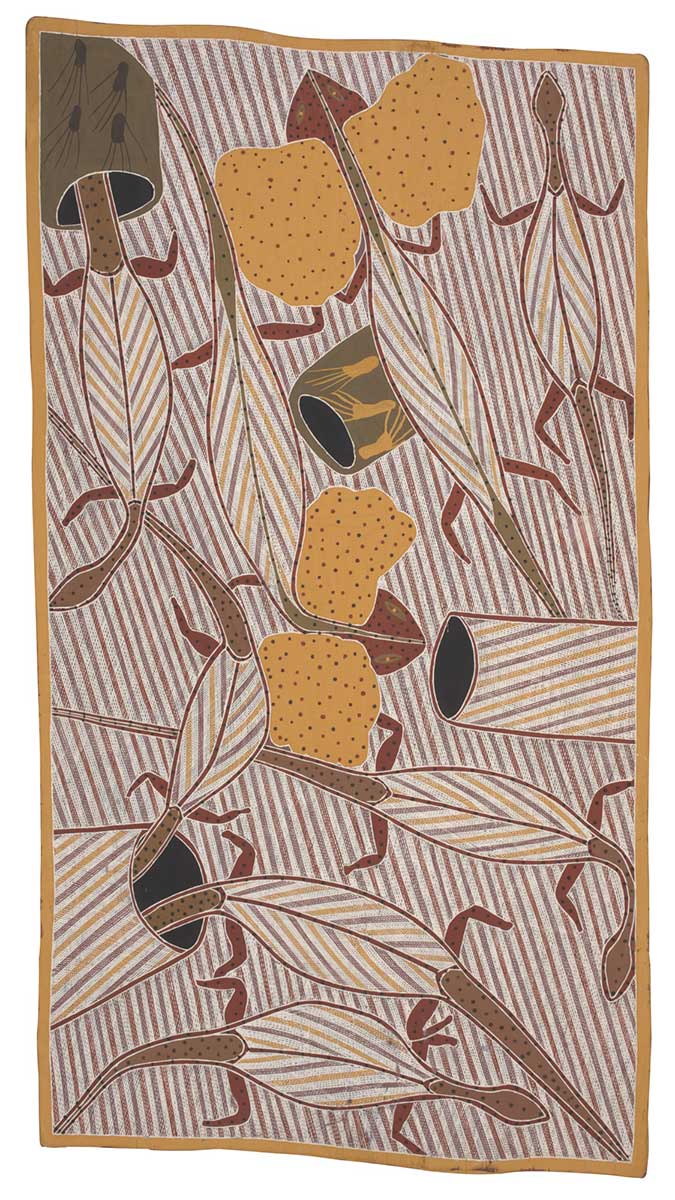

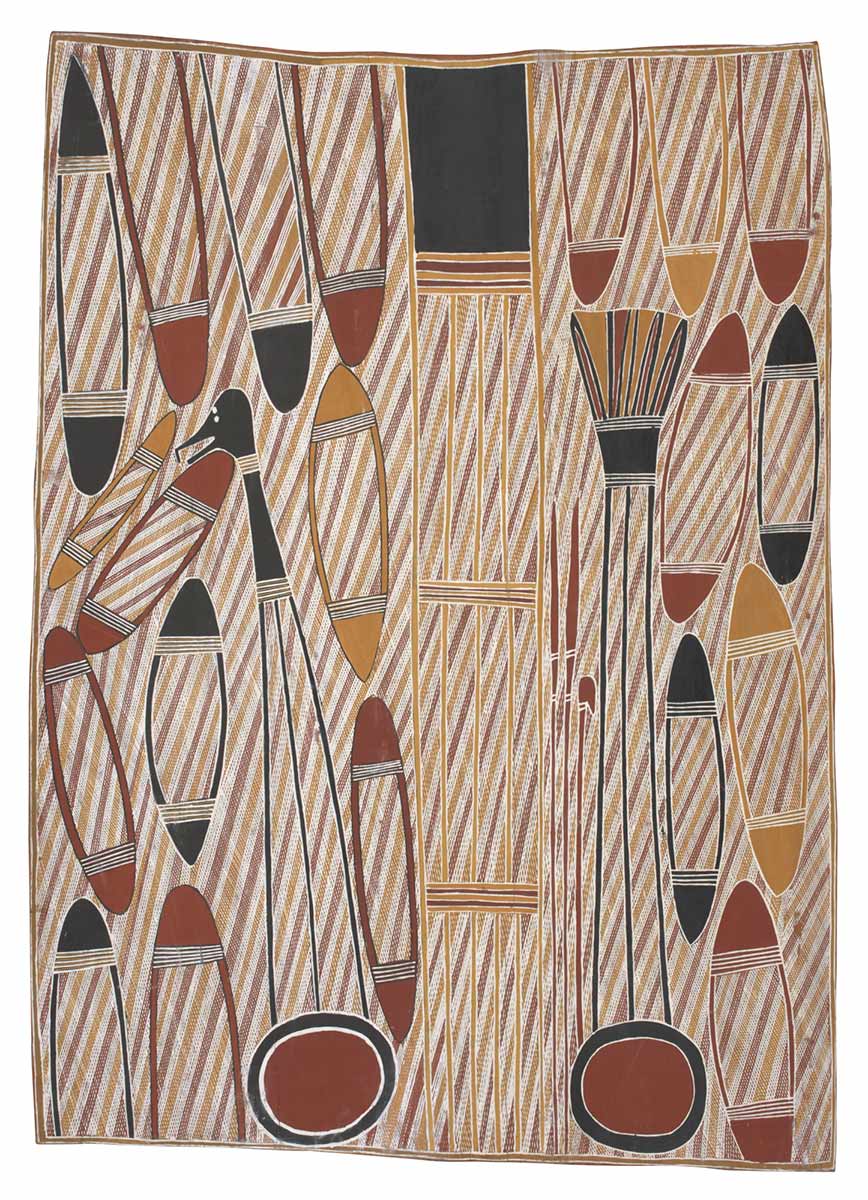

The Nyapililŋu are often represented by their digging sticks, wooden bowls and X-shaped breast girdles, rather than being drawn figuratively. The women are accompanied by Marrŋu the Possums, who run up and down the marrawili (native cashew or casuarina trees) spinning fur into string to create the sand dunes at Djarrakpi.

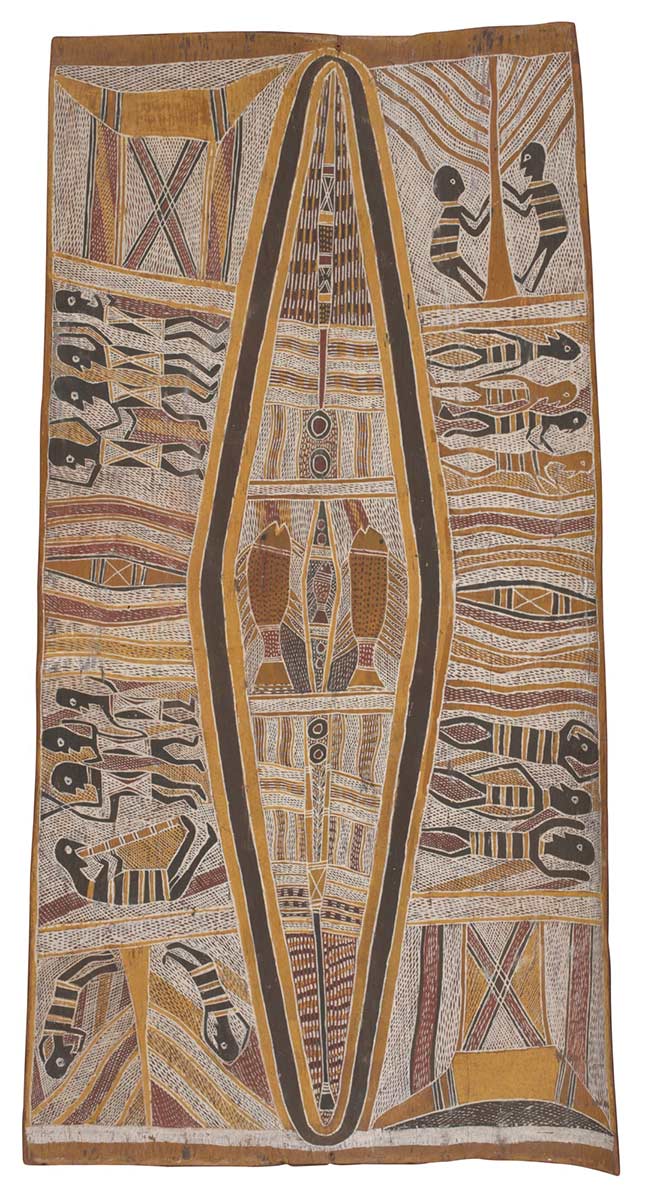

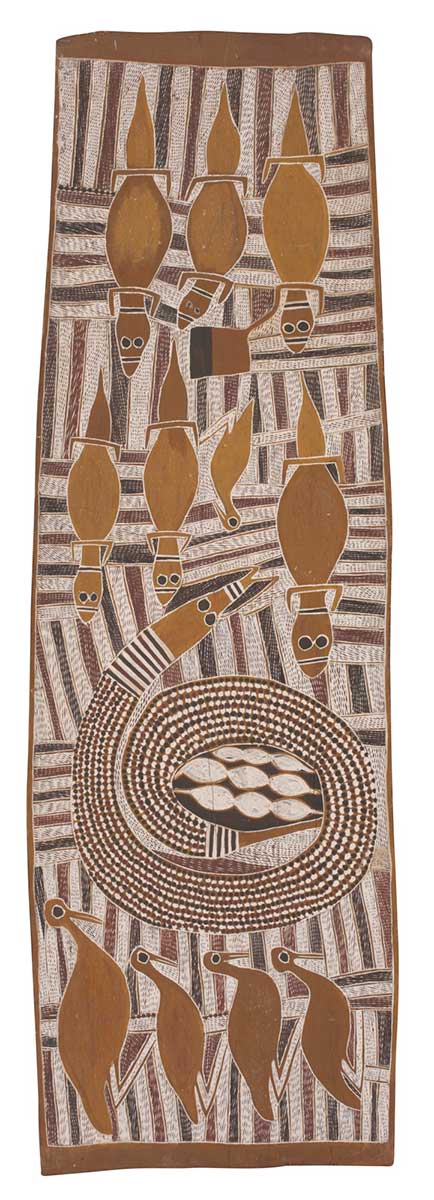

A recurring feature in Narritjin’s map-like paintings is the yiŋapuŋapu, an elliptical sand sculpture used in Yirritja mortuary ceremonies. Fish symbolising the body of the deceased are placed at the centre of the ground sculpture, while the anvil-shaped thunderhead cloud represents death. Sand crabs and maggots feed off the remains of fish in an act of cleansing. The yiŋapuŋapu at Djarrakpi connects to similar sand sculptures in Madarrpa and Dhalwaŋu clan lands on Blue Mud Bay.

The Gumana and Yunupiŋu dynasties of the moiety include the ceremonial leaders Birrikitji Gumana of the Dhalwaŋu clan, and Muŋgurrawuy Yunupiŋu of the Gumatj clan. Their atmospheric paintings evoke the freshwater rivers and fires of the Arnhem Land forests.

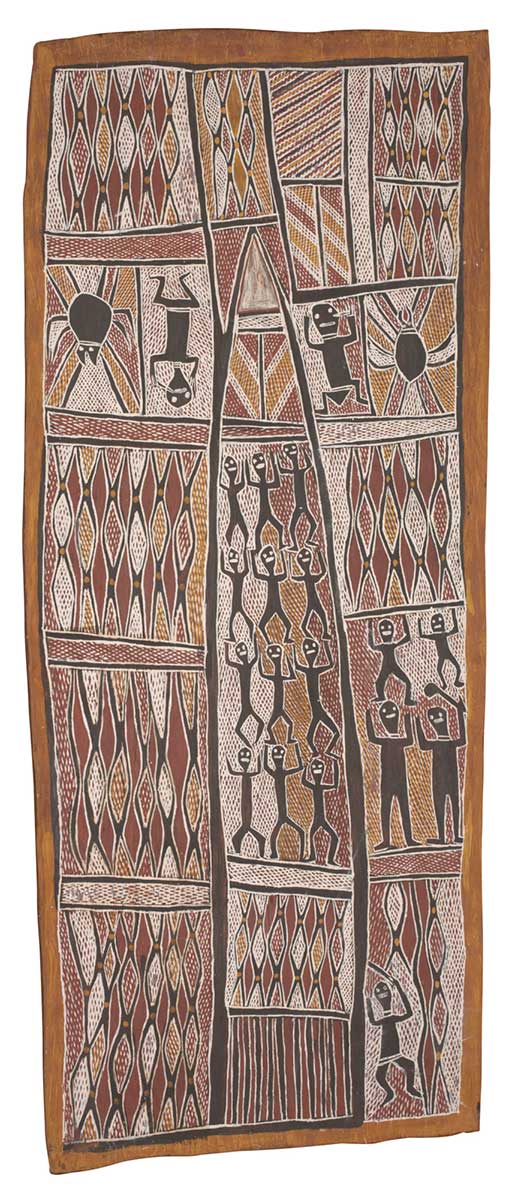

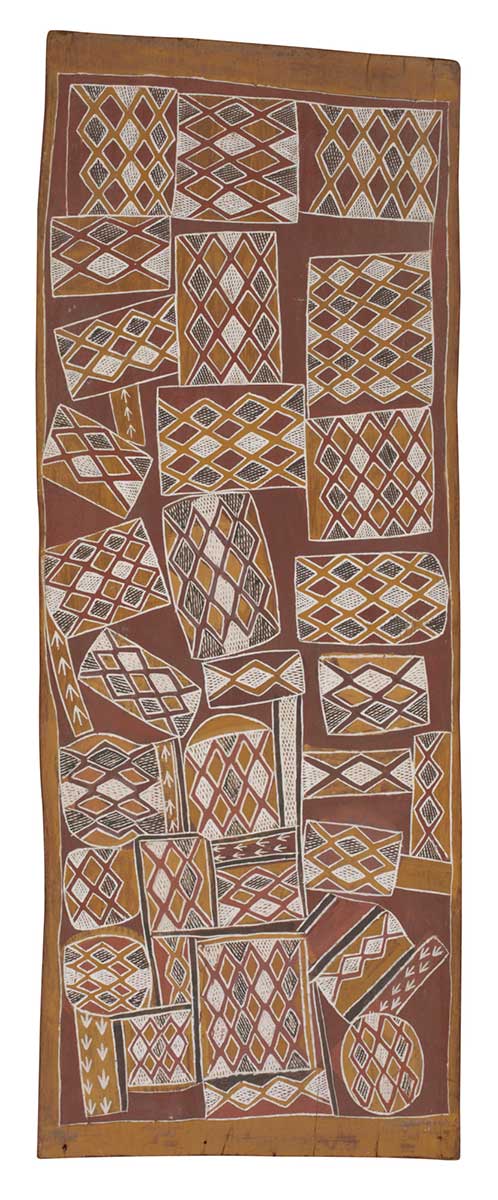

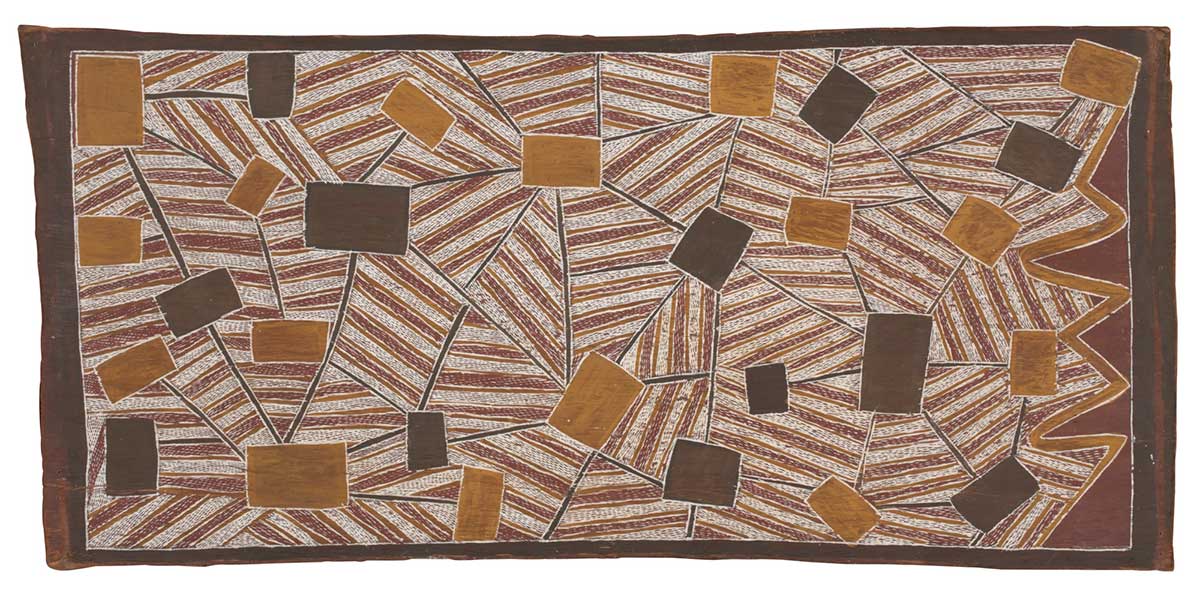

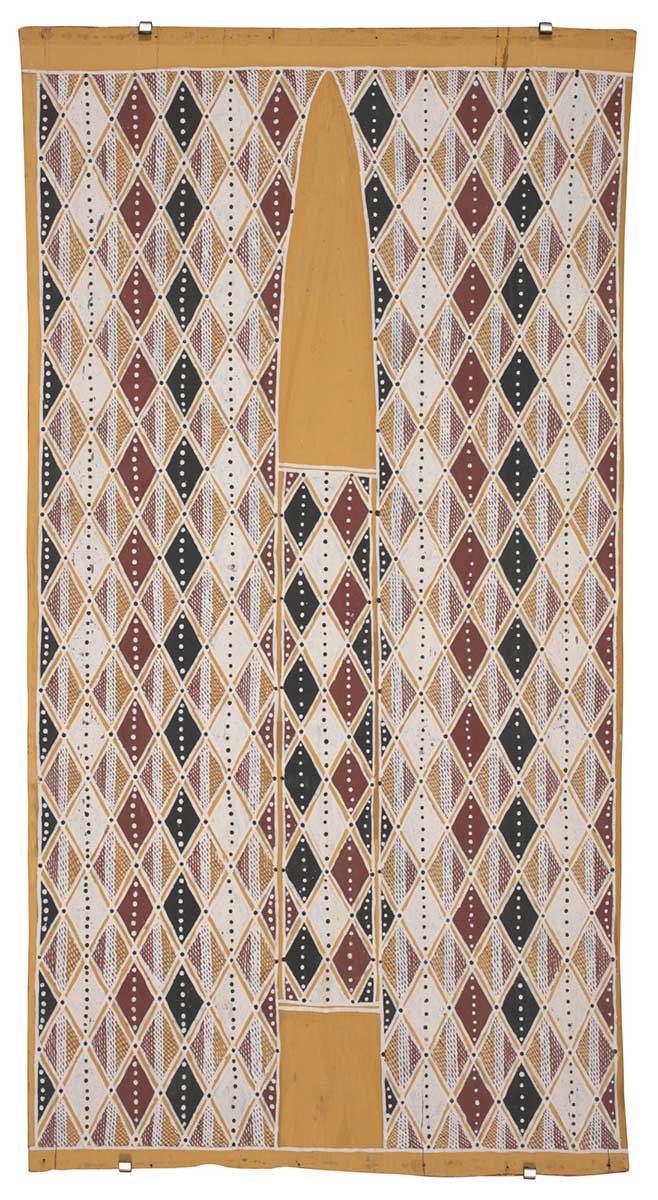

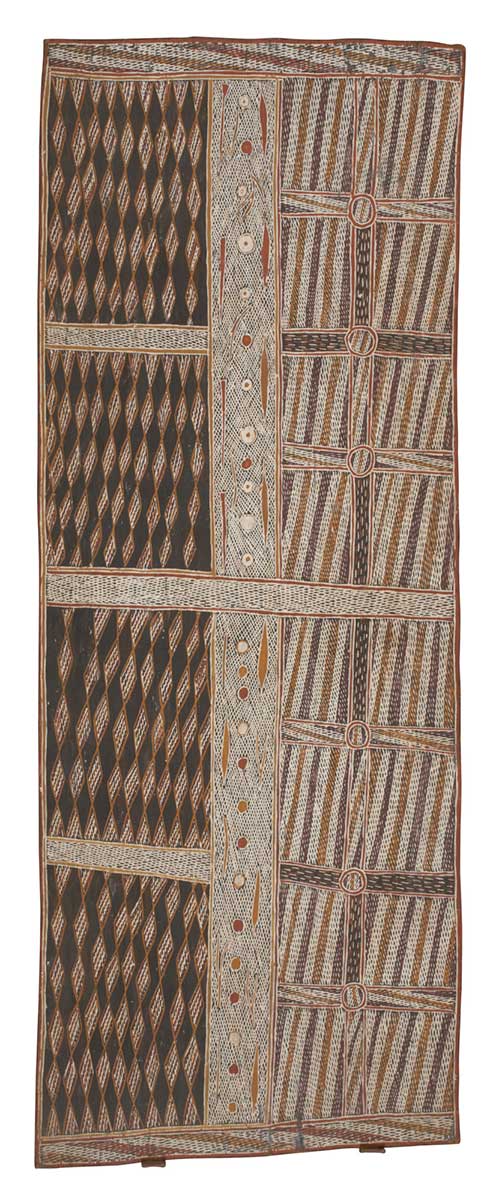

Muŋgurrawuy paints the ancestrally created fire that is used by Yolŋu as a land management technique known as firestick farming. The Great Bushfire Dreaming is a depiction of the use of fire to clear and regenerate the land, to prevent devastating wild fires and corral prey when hunting. The Gumatj miny’tji of linked diamond shapes seemingly shimmers with heat: the black, white and red crosshatching represents charred earth, smoke and ash, and burning cinders and fire respectively.

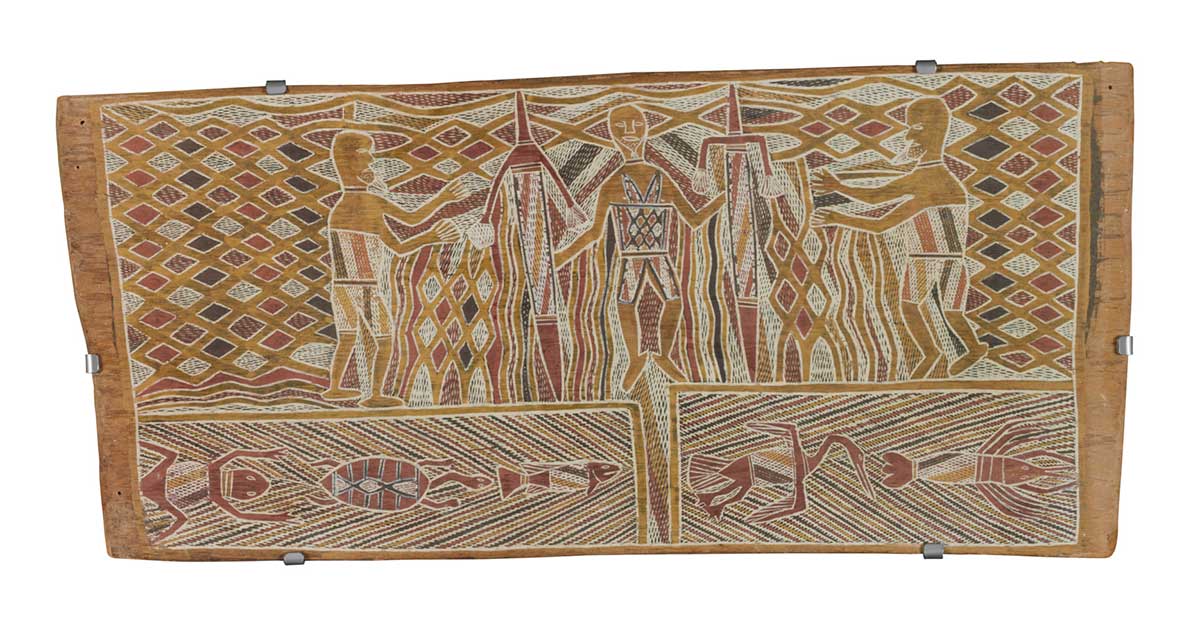

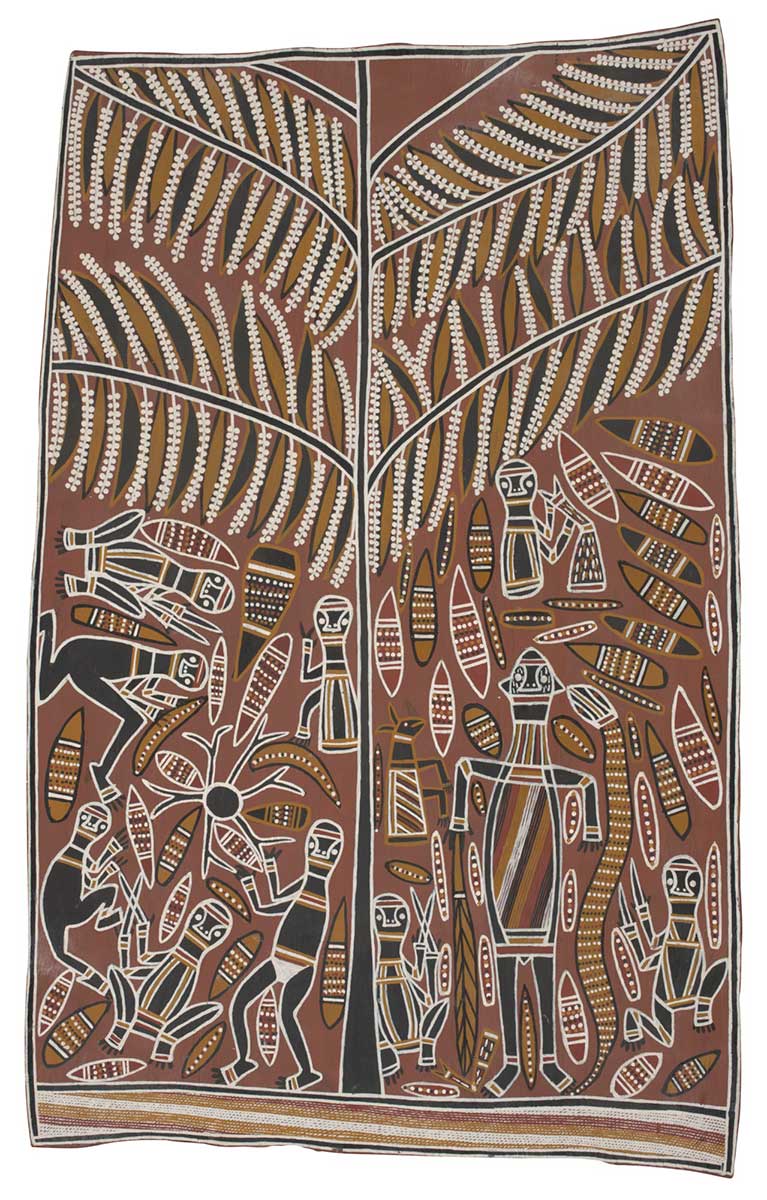

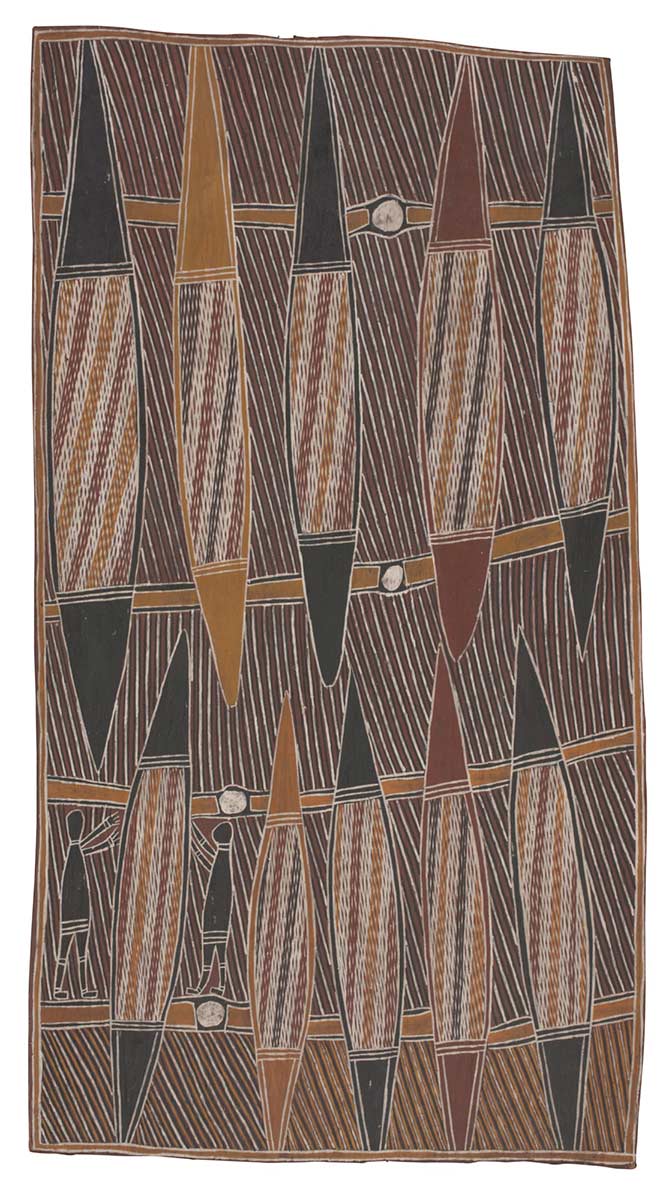

In Birrikitji’s The Four Great Yirritja Lawgivers, the figure in the lower left of the painting is the Yirritja ancestor Barama, who emerged at Gangan on the Koolatong River, his body covered in patterns made by salt water and with water weeds clinging to his skin. Barama instructed the other ancestors to distribute the law, miny’tji (sacred clan designs) and ritual objects among the Yirritja clans, as seen in Birrikitji’s son Gawirrin’s Barama Spreads the Sacred Law. The Dhalwaŋu clan pattern of linked rows of diamond shapes interrupted by an ellipse indicates the flowing fresh waters and billabongs of the Koolatong River.

Mutitjpuy Munuŋgurr had the authority to paint both Dhuwa and certain Yirritja themes. The Fire Dreaming at Yathikpa depicts the Yirritja Fire Dreaming site that is out to sea on Blue Mud Bay. The scene is reinterpreted abstractly by the patterns of linked diamonds: the red diamonds representing fire; the red crosshatching, sparks; the black diamonds, charcoal; and the white, ashes.

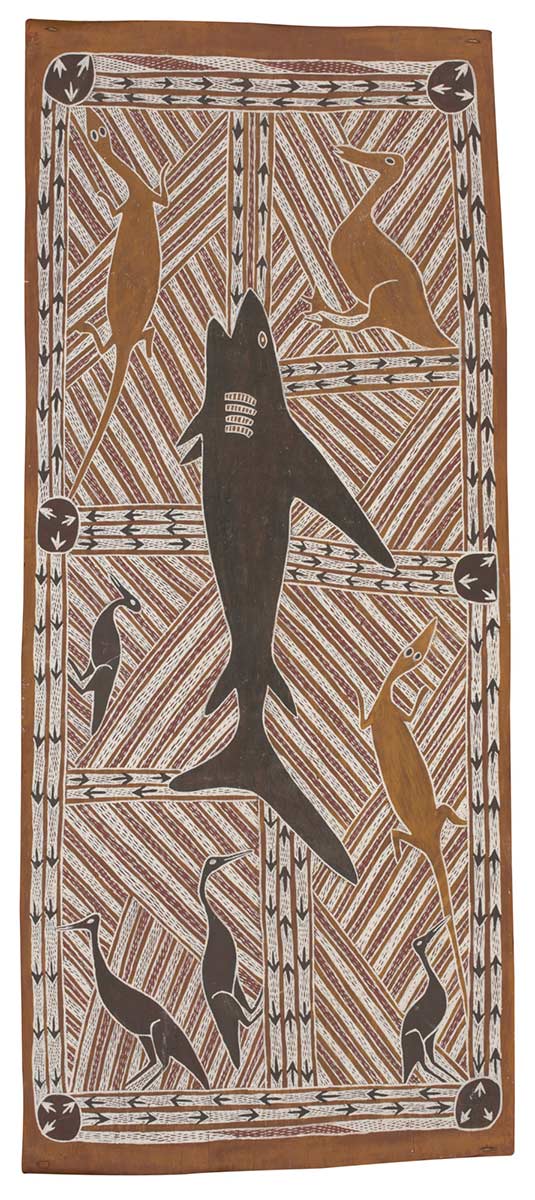

The grid structure in The Djan’kawu in Djapu Clan Territory with Mäna the Shark shows Mäna far inland in Djapu country, created by the Dhuwa ancestors, the Djan’kawu.

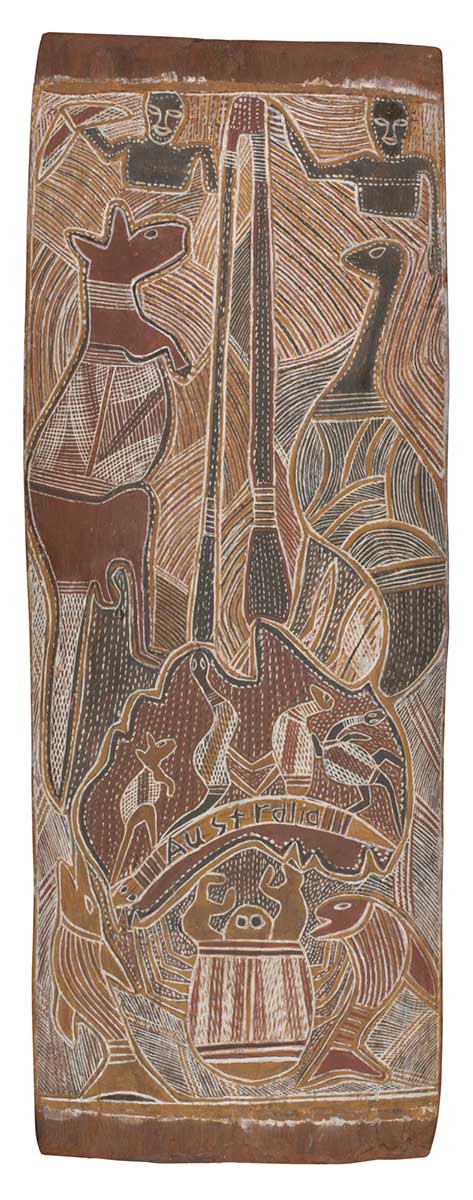

Mawalan Marika was the leader of the Rirratjiŋu clan and the head of an artistic dynasty that included his brother Mathaman and his son Wandjuk. The main ancestors of the Rirratjiŋu are the Djan’kawu, referred to in Wandjuk’s The Sacred Waterhole at Bilapinya, which features the Union-Jack-like design showing the paths the ancestors took as they created this freshwater spring.

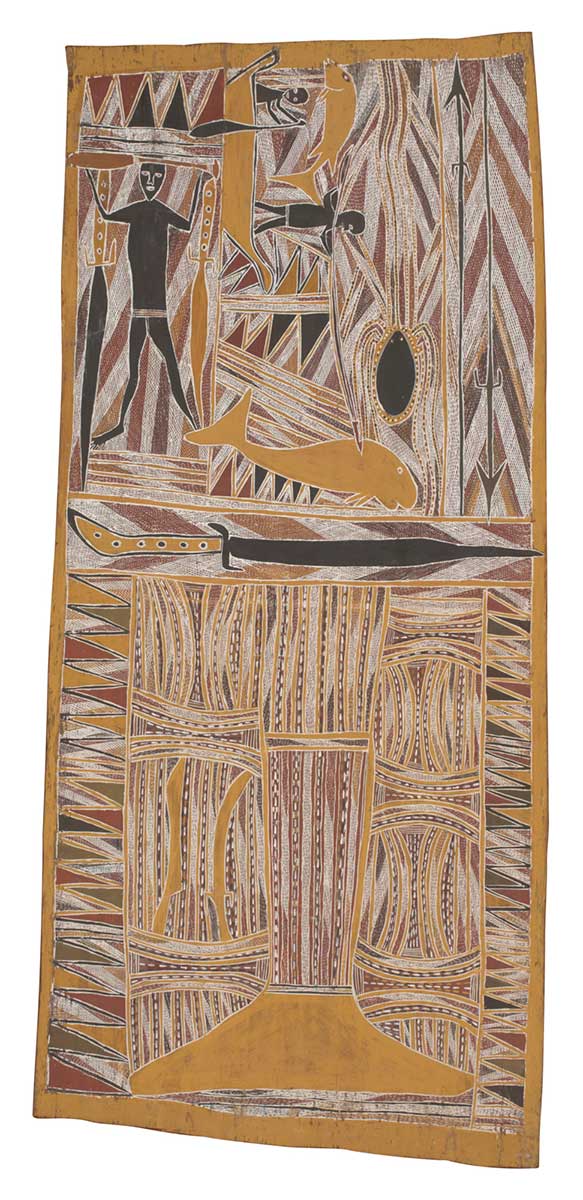

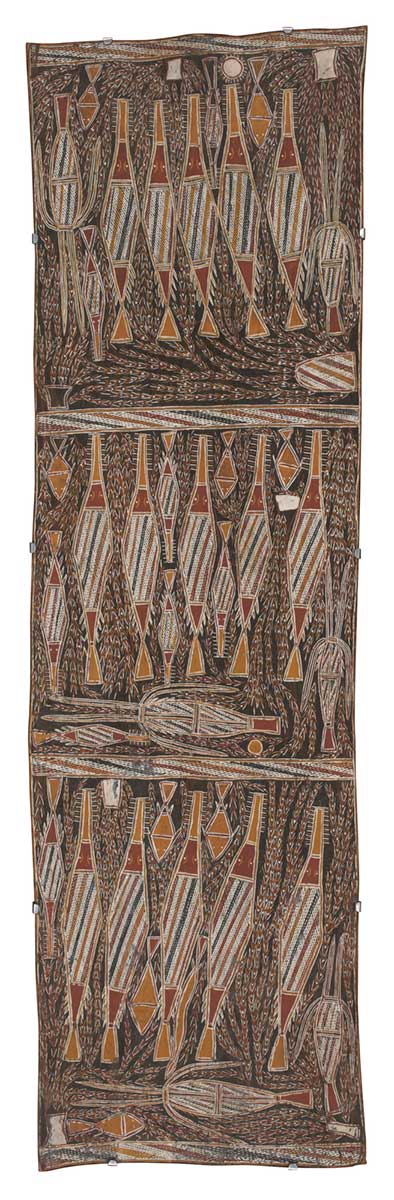

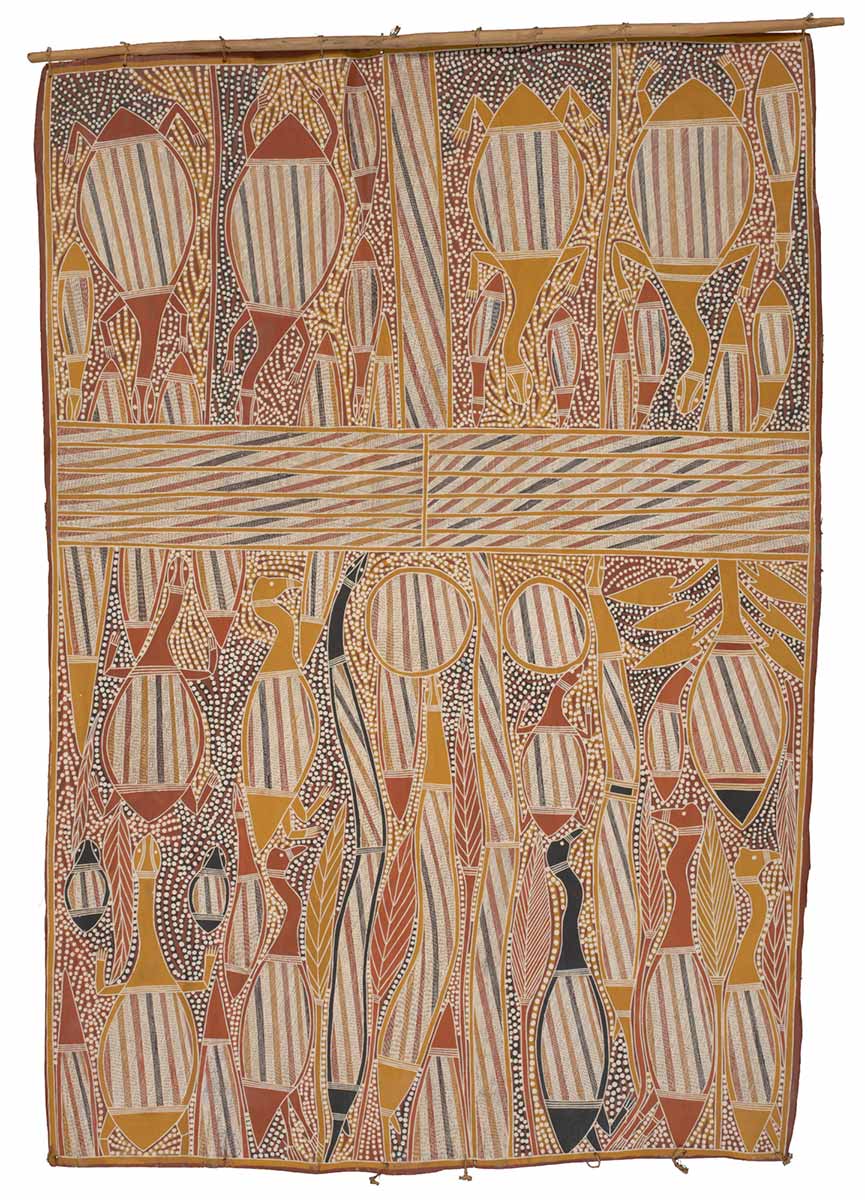

Mathaman paints another set of Dhuwa ancestors, the Wäwilak Sisters. In the upper panel of Rirratjiŋu Mortuary Ceremony the rays of the sun capture dust rising from the ground as people dance in the ceremony depicted below. Here, the spirit of the deceased is taught how to make paddles and is given a canoe to row to Dhambaliya (Bremer Island) on its way to the ancestral realm.

In Mawalan’s painting, the Milky Way is regarded as a river in the sky teeming with constellations in the form of totemic species. Wandjuk’s The Tail of the Whale Daymirri features the steel-bladed knives used to butcher a whale whose tail became a symbol of the thunderhead clouds of the early wet season. The anvil-shaped yellow cloud pouring rain appears upside-down in this orientation because the artist turned the bark around as he painted the picture.

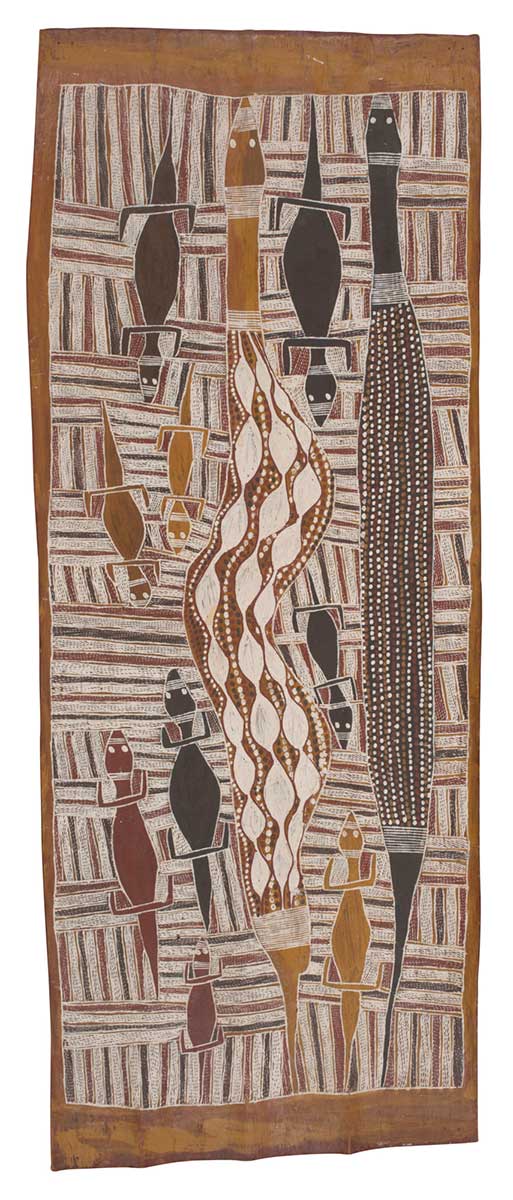

Mithinarri Gurruwiwi depicts the male and female Rainbow Serpents of his clan, the Gälpu. They feature in the Wäwilak Sisters story, in which Wititj the Rainbow Serpent swallows the sisters at Mirarrmina, then stands erect in the sky and boasts of his deed to ancestral Rainbow Serpents belonging to neighbouring clans, including the Gälpu. These serpents make Wititj aware he has broken the law by devouring beings who belong to the same moiety as him – a metaphor for a marriage between kin that is forbidden by law.

Wititj becomes ill and expels the women, as Mithinarri suggests in Wititj the Gälpu Python by depicting the legs of one of the sisters emerging from the snake’s anus. Just as Wititj at Mirarrmina created the first monsoon, the Gälpu snakes also make rain clouds, and their flickering tongues become lightning.

In Male and Female Wititj the extraordinary fertility of the snakes is emphasised by the depiction of eggs within the female’s body. The background Gälpu clan pattern represents paperbark trees.

In Wititj the Gälpu Snake, a goanna carries a rectangular quartz axe-head to make the connection between Gälpu country and Ŋilipitji, a site near Mirarrmina where quartz is quarried to make blades and knives.s

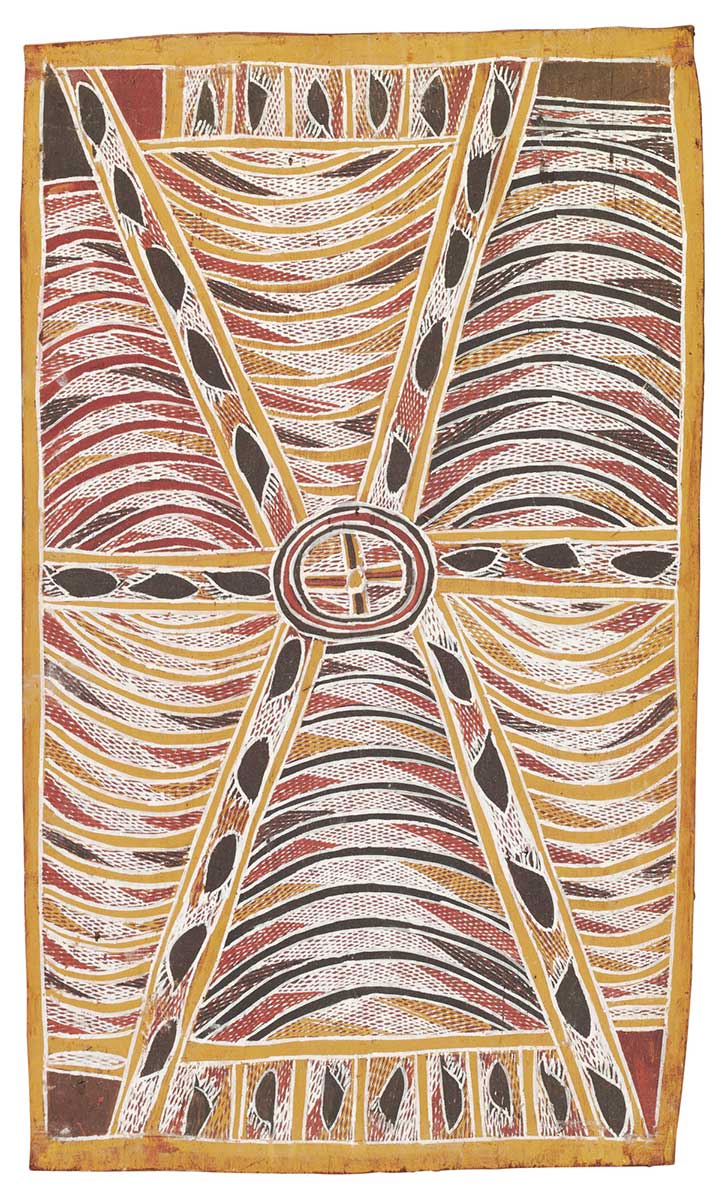

Abstraction in Western art history is a term applied to paintings of predominantly geometric forms or to images without obvious external referents. Abstract art emphasises the formal and expressive properties of line, shape and colour to elicit an aesthetic reaction beyond words. In Aboriginal bark painting there is an interplay between figurative and non-figurative imagery, between the representational and the abstracted, so that both may exist simultaneously within a painting.

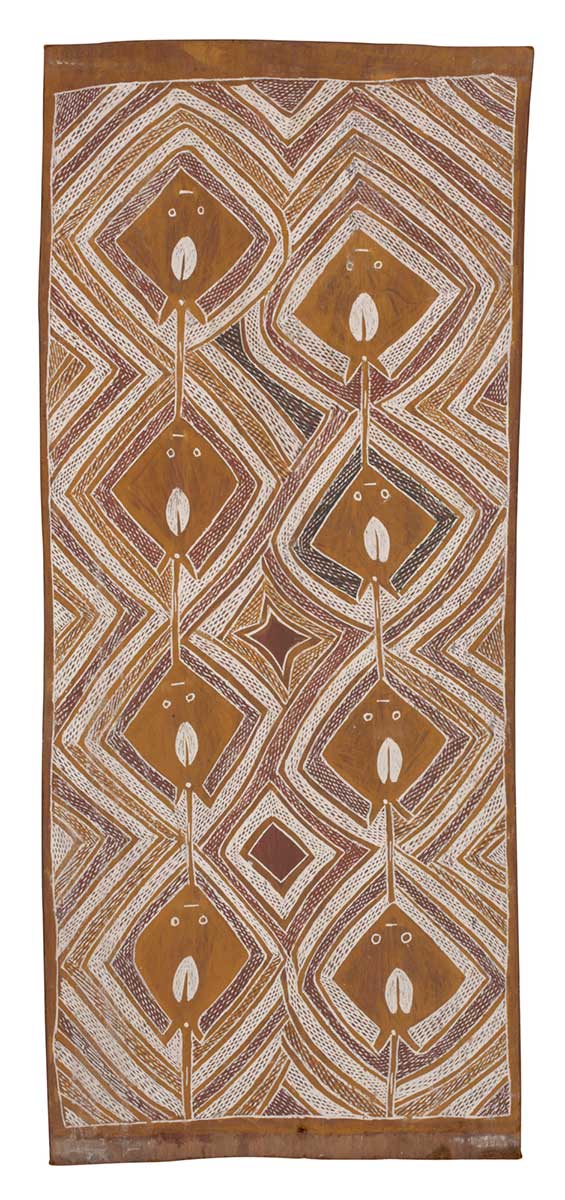

The landscape may be perceived as sets of abstracted patterns and designs. In several of Birrikitji Gumana’s paintings, regular rows of stingrays are surrounded by a Dhalwaŋu clan design to create a mesmerising pattern of eddies and pools of light reflected in the water.

By way of contrast, his Ŋärra Ceremony is a syncopated juxtaposition of sections of Dhalwaŋu body designs referring to fire. West Arnhem Land painter Bob Balirrbalirr Dirdi’s enigmatic tracery of yam roots and tubers may in fact double as an image of a serpent.

Mawalan Marika created a series of innovative ‘abstract’ paintings after his first visit to a big city – Sydney – in 1961. One of these captures his impression of buildings and roads seen from the air.

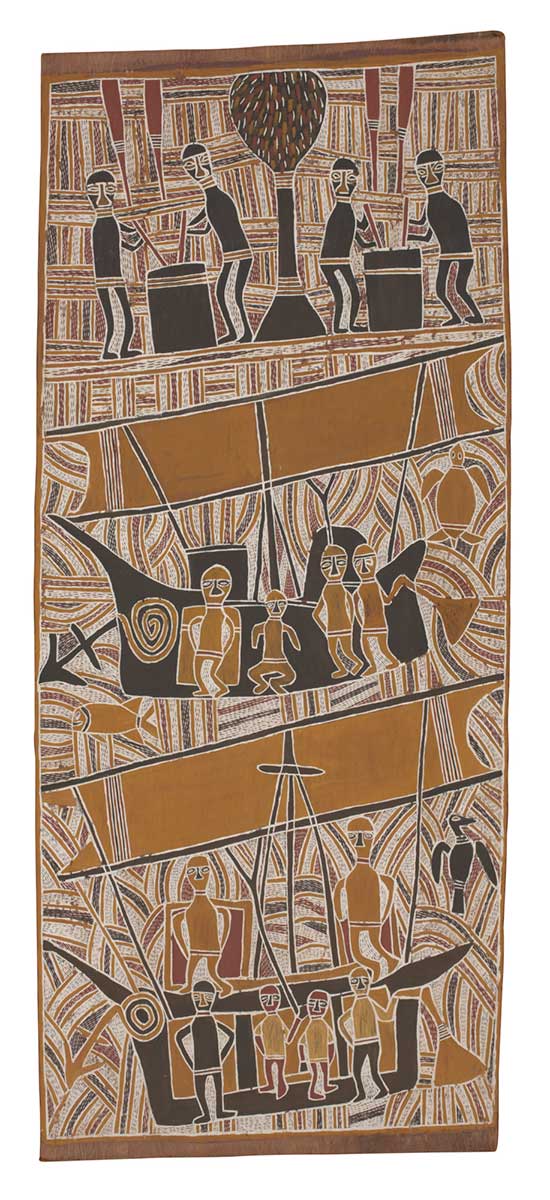

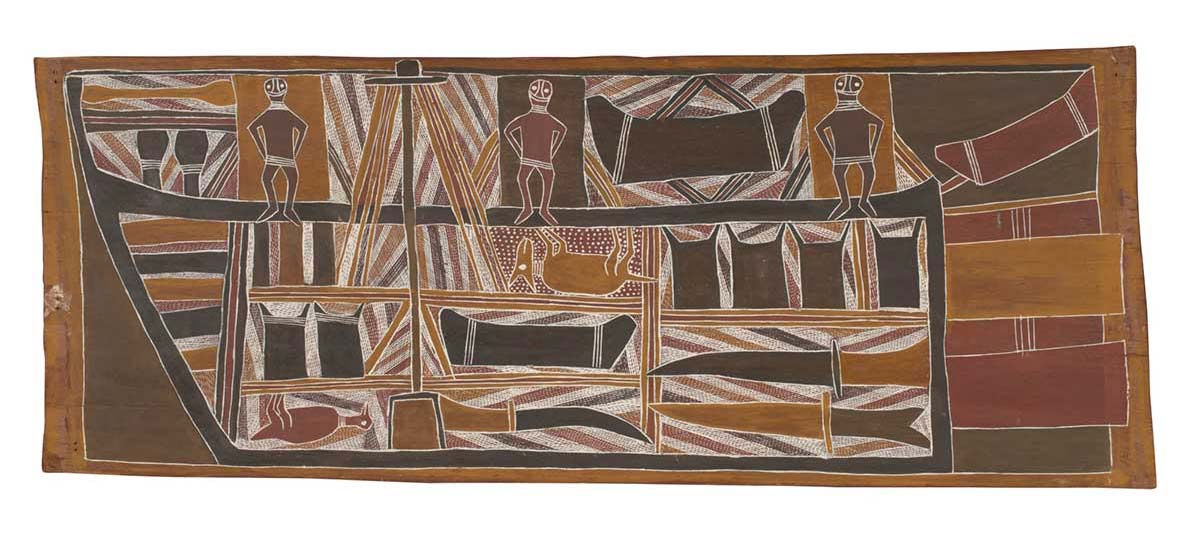

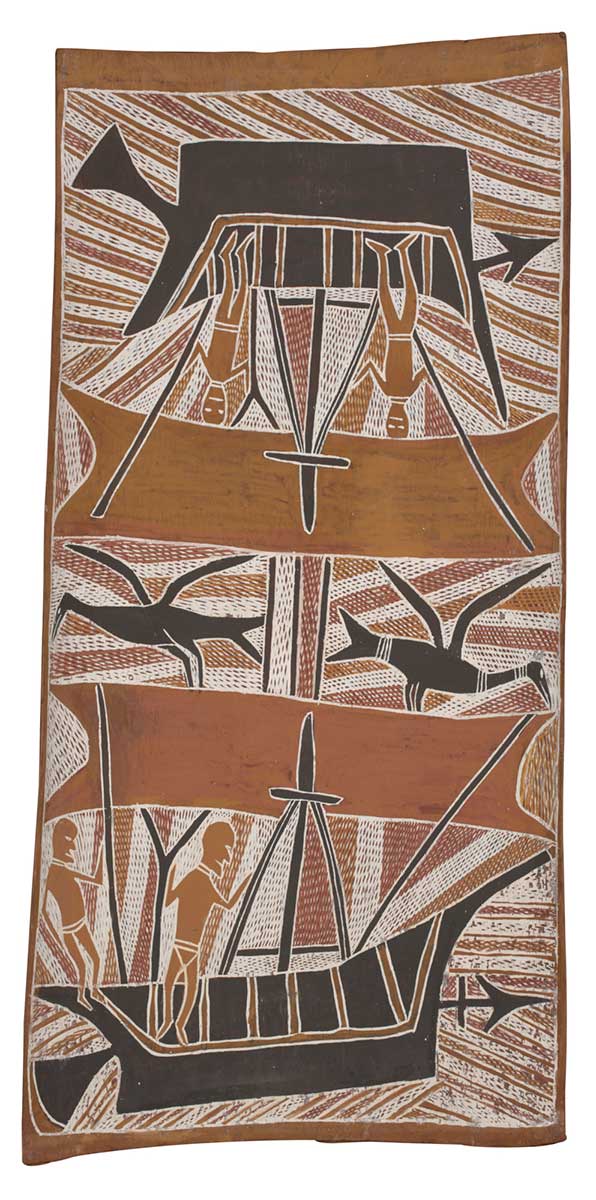

Trepangers from Makassar, in Sulawesi, Indonesia, visited the shores of Arnhem Land every wet season for more than 200 years until 1907, after the introduction of the government’s White Australia Policy. They came in fleets of prau to collect trepang (sea cucumbers), a delicacy in South-East Asia. The Makasar people established friendly relationships with Yolŋu, a number of whom sailed back with the visitors to Makassar and settled there.

The Makasar did not settle in Arnhem Land but they did have an influence on Yolŋu society and ritual. They introduced calico, tobacco and smoking pipes, and words that are still in use today, such as rrupiya (money). Most importantly they introduced an item of technology that transformed Yolŋu life – metal. Metal blades, knives and axes made everyday practices easier for Yolŋu, from cutting food to making large dugout canoes and complex wooden sculptures.

Although not part of the Dreaming, the Makasar did enter Yolŋu cosmology. The prau sail disappearing over the horizon at the end of the wet season, for example, is symbolic of the soul leaving this world for the ancestral realm. Birrikitji Gumana’s painting Makasar Prau recalls his meeting with the trepangers when he was young. Mathaman Marika uses variations of the Rirratjiŋu clan design to indicate dry land and the sea.

The artists of central Arnhem Land belong to the Yolŋu-speaking groups whose lands extend to the east coast of Arnhem Land.

Most people in this area moved from their traditional lands to the Christian mission on the island of Milingimbi after it was established in 1923, and to the postwar mainland settlements of Maningrida and Ramingining, before returning to their customary lands in the 1970s and 1980s.

In central Arnhem Land, the style of painting draws on elements of the figurative imagery of the west, and the detailed patterning and geometric compositions of the east.

Dawidi became the leader of ceremonies associated with the ancestral Wägilak Sisters on the death of his father, Yilkari Kitani (1891–1956). As Dawidi was still an inexperienced painter he was tutored by a senior artist, Dhawadanygulili (1900–1976). When Dawidi died, his brother Paddy Dhäthaŋu inherited his role.

The Wägilak story concerns the rules of marriage, the creation of the first monsoon and the concept of transformation. In the narrative, Wititj the Rainbow Serpent swallows the Wägilak Sisters but regurgitates them when he realises they belong to his moiety, the Dhuwa. The sequence of swallowing and regurgitation is a metaphor for transformation, as in initiation where boys enter the ceremony and emerge as men.

The Djan’kawu – two sisters and their brother – are the major ancestors of the Dhuwa moiety. They created the first human beings and organised them into clans, allocated land and provided fresh water by plunging their digging sticks into the ground. They came to Arnhem Land from the east, across the sea.

Djunmal’s The Sea Voyage of the Djan’kawu Sisters depicts sea creatures that the ancestors saw as they paddled ashore. Tom Djawa’s Emu Dance shows two inland sites they created. The Union-Jack-like design represents the Djan’kawu, and the circles are freshwater wells. In Valerie Munininy 2’s painting a variation of the Djan’kawu design is shown among beds of oysters, at a site called Gärriyak.

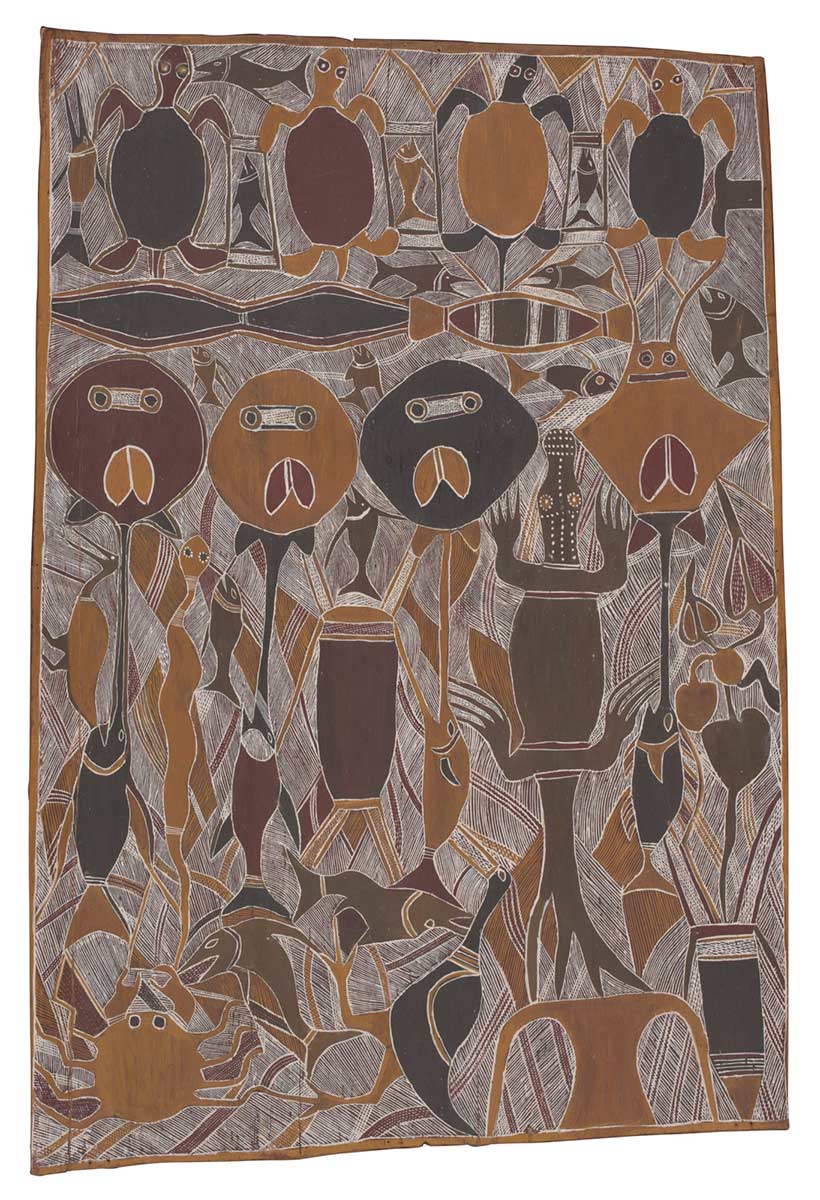

The Djan’kawu arrived with the dawn and are linked to Banumbirr the Morning Star, which is symbolised by the yam plant. In Bartji (Jungle Yams), Jack Wunuwun, a master of the visual pun, has drawn the tubers of the plant in profile to suggest the human body with arms outstretched, as if performing in ceremony. He has transformed his subject from one realm to another, from the natural world to the ancestral. The vines of the yam plant symbolise the feathered string that ancestral beings attach to Banumbirr the Morning Star on its daily pre-dawn journey heralding a new day.

David Malangi used to joke that he was the most popular painter in Australia. His image of the burial of Gurrmirriŋu the Ancestral Hunter was reproduced on the $1 note when decimal currency was introduced to Australia in 1966. As Malangi used to say, most Australians carried his painting in their wallets.

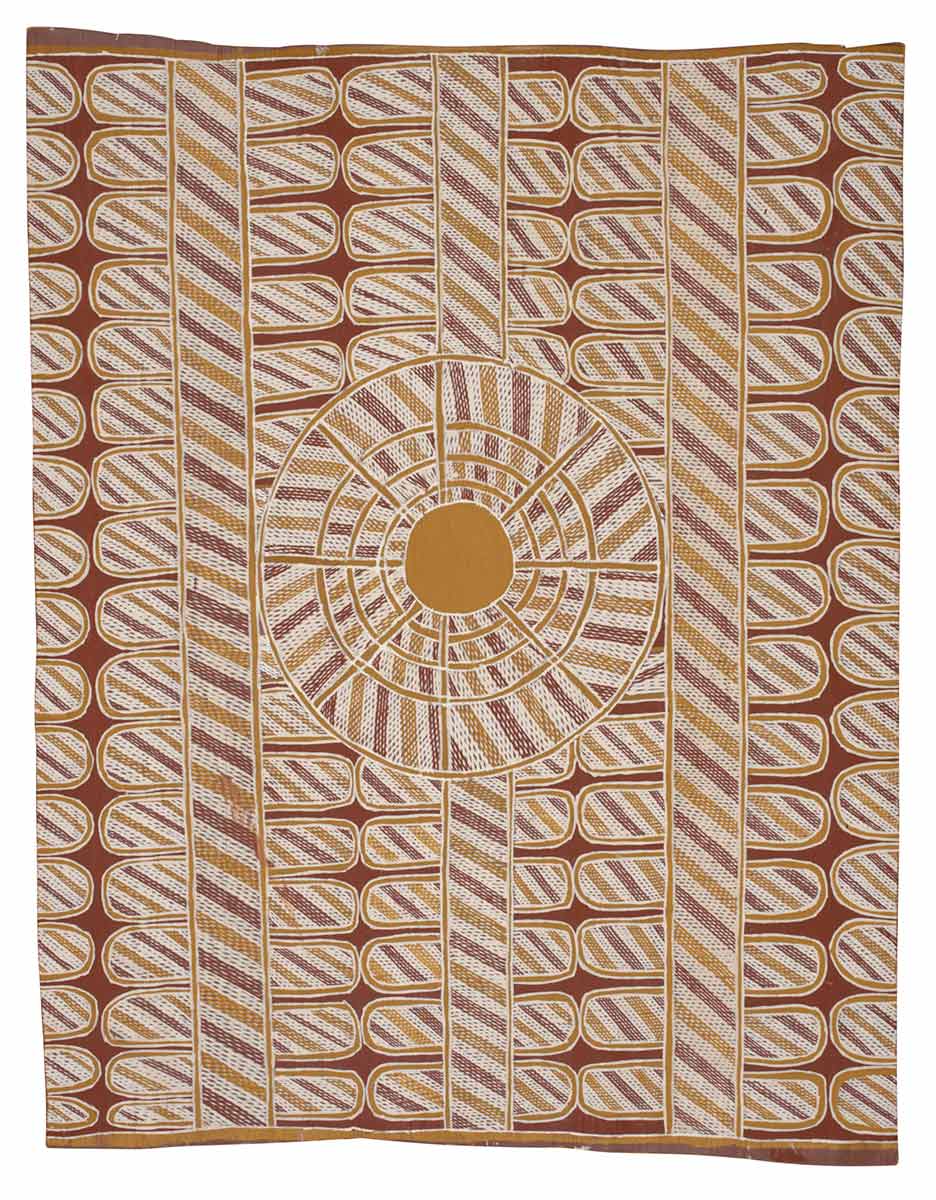

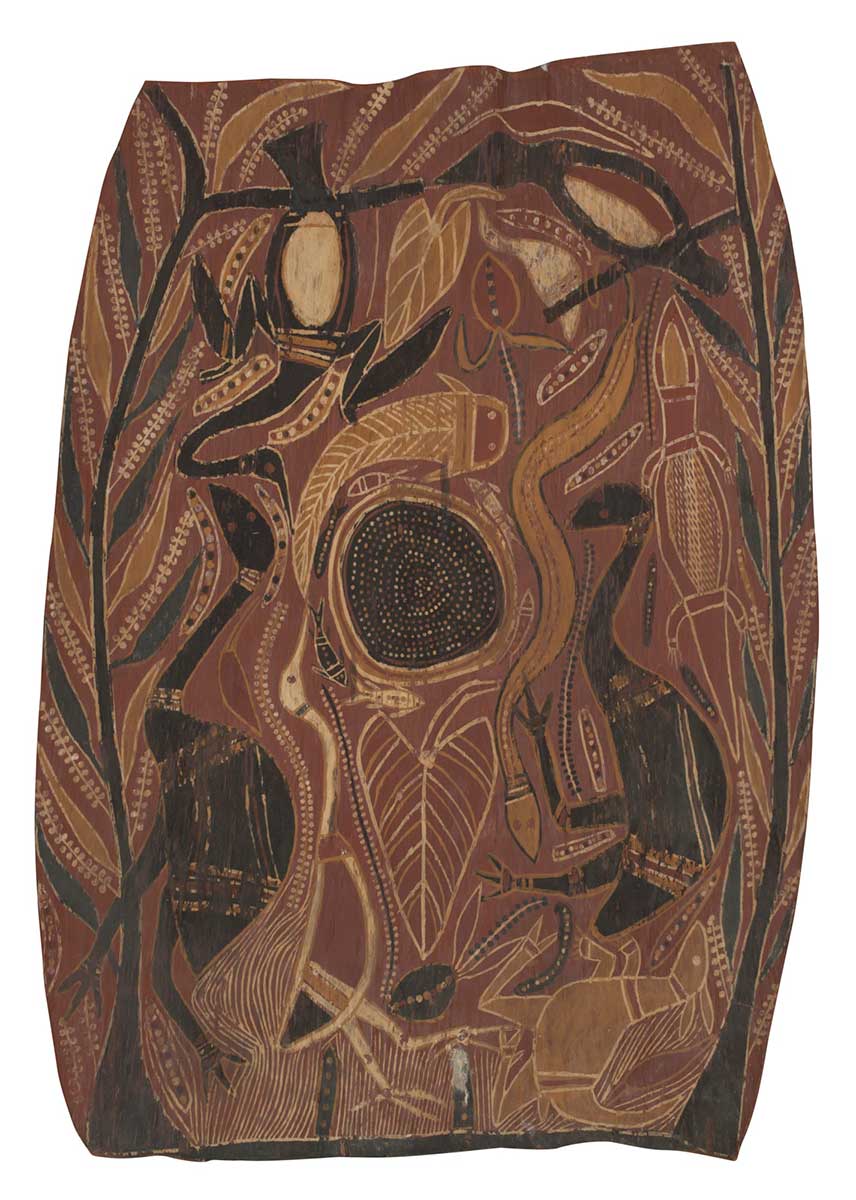

Malangi paintings show aspects of the story of Gurrmirriŋu, who died from the bite of a venomous snake. The Manharrŋu clan performed the first burial ceremony for him while a mortuary feast was prepared beneath a wurrumbuku (white berry tree). Gurrmirriŋu’s body was painted with the Manharrŋu clan design. Waterhole Life shows totemic animals surrounding the clan waterhole, which contains the souls of clan members. The central positioning of the waterhole reflects its significance to a person’s identity. When a clan member dies, a diver duck descends into the waterhole and plucks their soul from the circle of life.

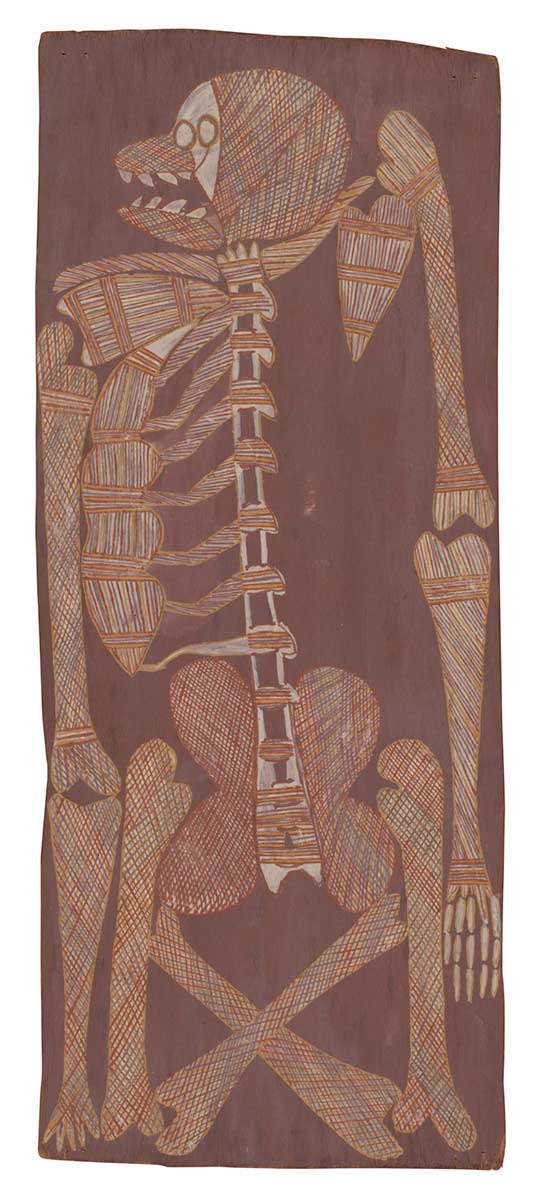

Malangi had a unique way of drawing dangerous spirit figures. He often incorporated elements of X-ray drawing to show the skeleton and internal organs of his subjects. X-ray is normally associated with painting in western Arnhem Land. The Dead Gurrmirriŋu depicts the hunter’s body in a state of decay as birds eat at his flesh in a symbolic act of purification.

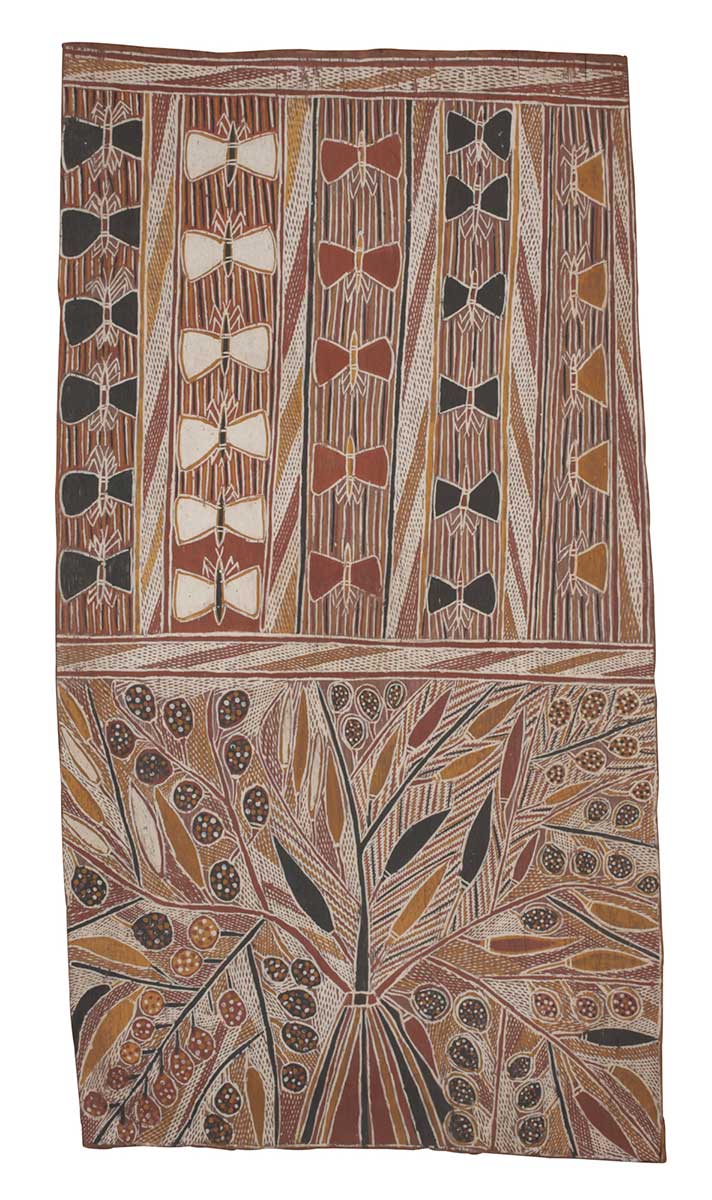

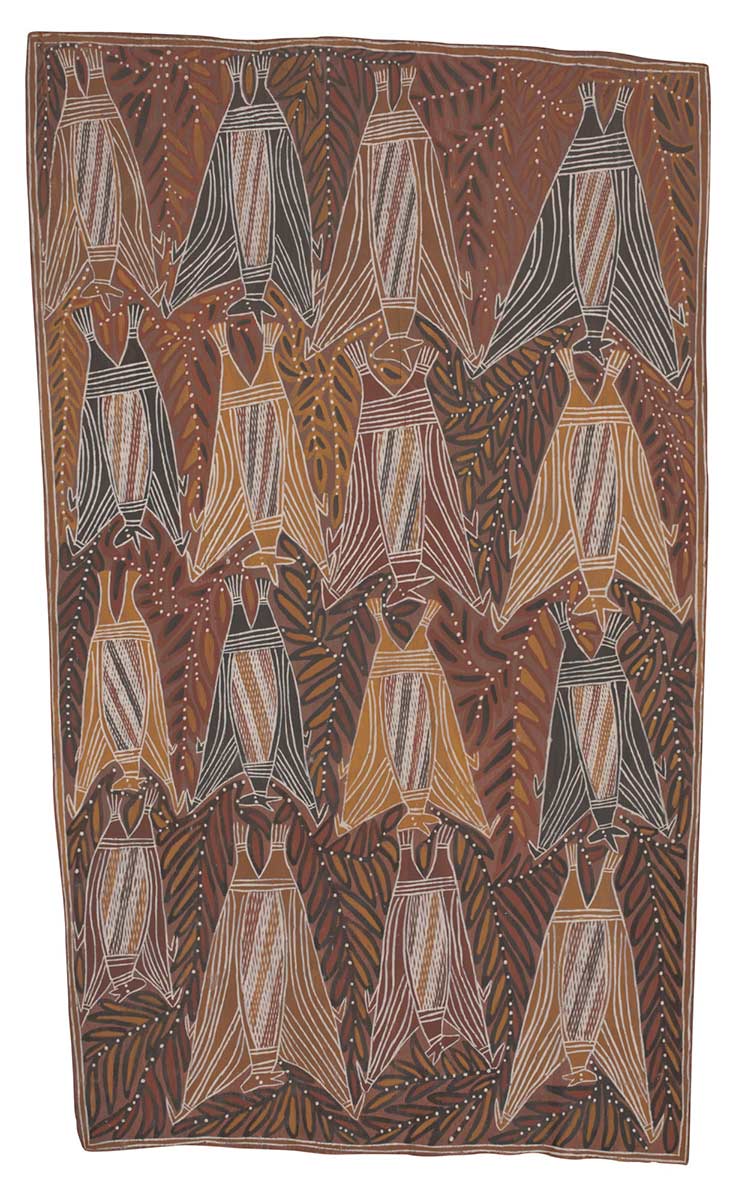

George Milpurrurru and his kinsman John Bulunbulun’s traditional lands lie in and around the Arafura Wetlands. It is a landscape teeming with wildlife and lush with vegetation. Ancestral flying foxes (fruit bats) are the custodians of Ŋlyindi, a major sacred site in the region. Milpurrurru has depicted the creatures in organised rows, and drawn them to resemble ceremonial objects such as the staffs in Raŋga (Ritual Objects) for the Yirritja Flying Fox Dance. The regularity of these compositions suggests the rhythms of ceremonial dance.

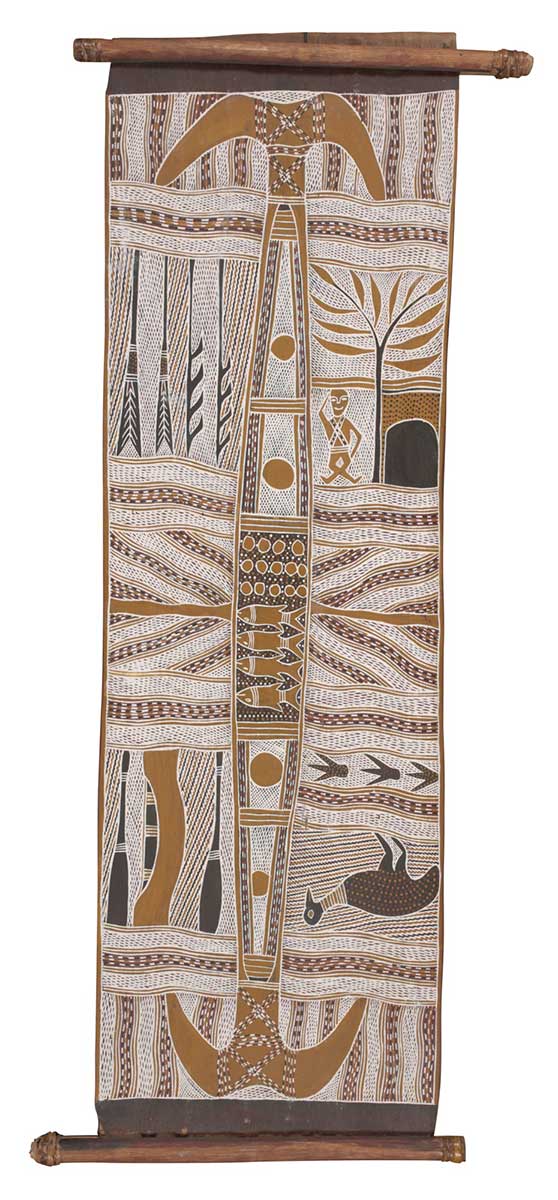

Shown in the centre of Ganalbiŋu Funerary Rites is a vertical log-coffin to house the bones of a deceased clan member. The bone burial ceremony marks the safe arrival of the soul to the ancestral realm and the end of the mourning period. All the elements in the painting – the coffin, the ritual objects and the magpie goose and waterlily totems – are decorated in the same clan pattern as the background, allowing them to take on an aura of invisibility to evoke the presence of sacred ancestral forces within the ceremony – and within the painting itself. Binyinyuwuy’s painting is another version of the same ceremony.

Milpurrurru’s Galawu (Stringybark House) depicts two types of bark hut: the curved shelters built on the ground in the dry season, and the platform shelter on stilts for the wet season. ‘Galawu’ also describes the large sheets of bark used for painting.

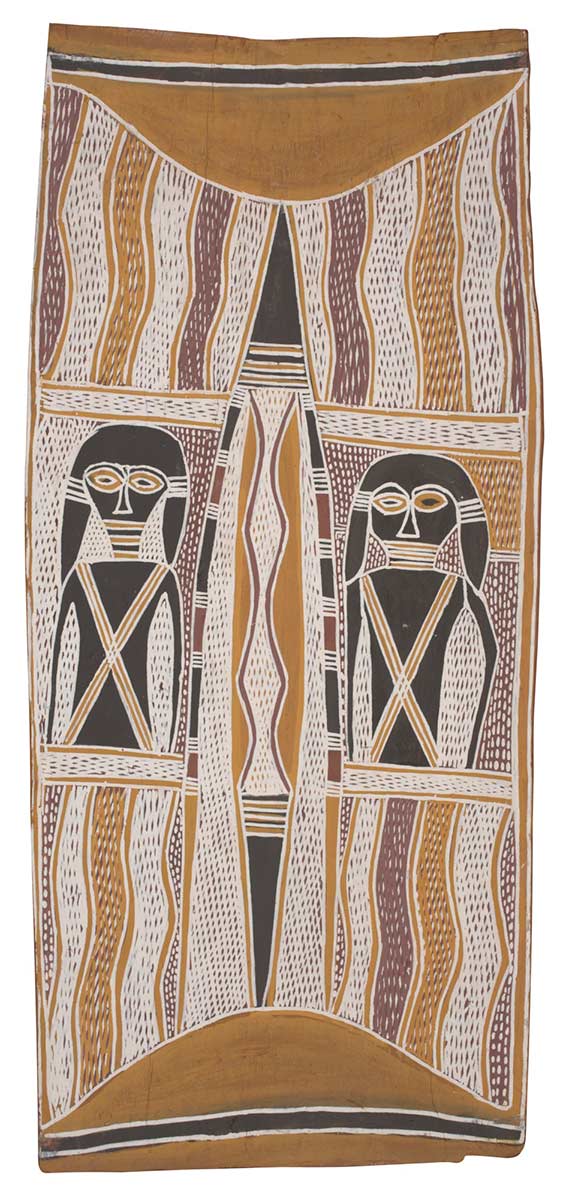

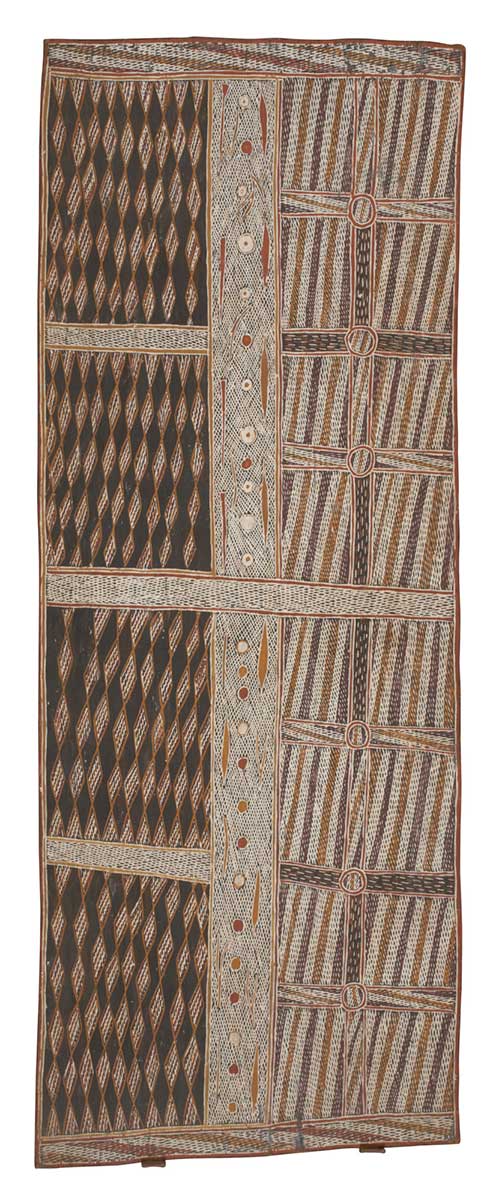

Portraits of people, as the representation of their physical appearance and facial likenesses, are not part of the traditional Aboriginal artist’s repertoire. To Bininj and Yolŋu, a person’s identity – their kinship ties, totemic associations, clan group and connections to ancestors and country – is of much greater significance.

The two paintings here may be regarded as self-portraits of the artists Harry Makarrwala and Jimmy Wululu. Makarrwala belonged to the Wangurri clan. His clan design represents the patterns made by milka (mangrove worms) on a sacred log. The extensions at the top of the work mimic body painting arching over the shoulders.

Wululu belonged to the Daygurrgurr clan of the Gupapuyŋu group, and his primary totem was Niwuda (honey or sugarbag), associated with the Honey Ancestor Murayana at Djilwirri in central Arnhem Land. The diamond pattern shows the bees’ hive, with cells in various stages of development, within the trunk of the tree that appears in the centre of the painting.

The artists featured here are, quite literally, Australia's old masters and their work constitutes a peerless artistic canon. Many of them were also ritual leaders, statesmen and cultural advocates. Together, they carried one of the oldest traditions of art known to man – Aboriginal art – into a new era, to establish its place in the world.

Curly Bardkadubbu

Born clan, Kuninjku language, Duwa moiety. 1924–1987

Bardkadubbu rose to prominence as a painter in the late 1970s. He was tutored by Yirawala in the early 1970s when they shared outstations at Table Hill and Marrkolidjban, which both men had helped to establish. Later, he moved to Namokardabu, also in the Liverpool River region.

Bardkadubbu’s work was selected for a number of major exhibitions in Australia and abroad, including: The Art of Aboriginal Australia, which toured North America from 1974 to 1976; and Aboriginal Art: The Continuing Tradition at the National Gallery of Australia in 1989. Bardkadubbu entered the first National Aboriginal Art Award, established by the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory in 1984.

Binyinyuwuy

Djarrankuykuy clan, Djambarrpuyŋu language, Dhuwa moiety. 1928–1982

Binyinyuwuy was a consummate, prolific and influential artist of high ritual authority, which gave him the rights to paint an array of subjects belonging to his moiety, the Dhuwa, and those of the Yirritja.

He was a driving force among the group of artists on Milingimbi during the 1960s, which included Tom Djäwa and David Malangi.

His work forms part of a number of celebrated collections, including those of the major state art museums, the Arnott’s Collection at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, museums in Paris and Basel, and the Kluge-Ruhe Collection at the University of Virginia.

John Bulunbulun

Gurrumba Gurrumba clan, Ganalbiŋu language, Yirritja moiety. 1946–2010

Bulunbulun was a renowned healer and ceremonial singer as well as a major painter of his generation. He was one of the first Yolŋu artists to become a professional printmaker. In the 1970s he collaborated with his kinsman George Milpurrurru and the anthropologist Joseph Reser on a study of traditional Yolŋu housing.

In 1993 Bulunbulun led a group of Yolŋu performers to Ujung Pandang (Makassar) in Sulawesi to stage a ceremony, Marayarr Murrukundja, that re-established relations between the Ganalbiŋu and the Makasar. His work has been included in several seminal exhibitions of Aboriginal art, including Aratjara, which toured Europe in 1993–94.

Dawidi

Galwanuk clan, Liyagalawumirr language, Dhuwa moiety. About 1921–1970

Dawidi inherited the role of ritual leader of the Liyagalawumirr when his father, Yilkari Kitani, died in 1956. Too inexperienced to assume full responsibility for the role at the time, he was aided by his uncle, Tom Djäwa, and was tutored in art by Dhawadanygulili (1900–1976) until about 1963.

Dawidi’s major subject is the Wägilak Sisters story, and the paintings in this exhibition reflect his artistic maturity. He featured prominently in the exhibition The Painters of the Wagilag Sisters Story 1937–97 at the National Gallery of Australia in 1997. He is represented in major public collections in Los Angeles, Paris and Basel, as well as within Australia.

Paddy Dhäthaŋu

Galwanuk clan, Liyagalawumirr language, Dhuwa moiety. About 1915–1993

Dhäthaŋu became a ceremonial leader of the Liyagalawumirr clan, with particular responsibility for ceremonies concerning the Wägilak Sisters, when his predecessor, Dawidi, died. As a boy he was taken to Milingimbi once the mission was established there, and he lived through the bombing of Darwin during the Second World War.

Dhäthaŋu was a major contributor to The Aboriginal Memorial (1988) at the National Gallery of Australia, and often collaborated with Dorothy Djukulul (born 1942), one of the first women painters in central Arnhem Land. In 1987 he painted a mural for the Darwin Performing Arts Centre and in 1992 was awarded an emeritus fellowship by the Australia Council for his contribution to the arts in Australia.

Bob Balirrbalirr Dirdi

Barrbinj clan, Kuninjku language, Yirridjdja moiety. About 1905–1977

The earliest recorded bark paintings by Balirrbalirr were collected by the anthropologists Ronald and Catherine Berndt in the 1940s. His work was included in the Berndts’ influential exhibition The Art of Arnhem Land at the Western Australian Museum in 1957. This exhibition was the first to identify Aboriginal artists by name and clan.

Balirrbalirr was later represented in other major exhibitions, including: Australian Aboriginal Art, an Art Gallery of New South Wales exhibition that toured the country in 1960–61; The Art of Aboriginal Australia, which toured North America in 1974–76; Kunwinjku Bim at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1984; and Keepers of the Secrets at the Art Gallery of Western Australia in 1990.

Tom Djäwa

Daygurrgurr clan, Gupapuyŋu language, Yirritja moiety. 1905–1980

Djäwa was a senior ceremonial leader and artist who was acutely aware of the need to document Gupapuyŋu culture to ensure its continuity.

He recorded songs with the ethnomusicologist Alice Moyle and played a major role in two documentary films by Cecil Holmes: Faces in the Sun (1963) and Djalambu (1964).

From 1960 his work was included in a number of historically significant exhibitions in Australia and overseas, and he is represented in major collections in Paris and Basel, and in the Kluge-Ruhe Collection at the University of Virginia.

Djunmal

Mayarrmayarr clan, Liya’gawumirr language, Dhuwa moiety. About 1920–1975

Djunmal was a senior ritual leader of the Liya’gawumirr people and was known for always wearing sunglasses.

Along with Narritjin Maymuru and other Yolŋu, Djunmal participated in the acclaimed Aboriginal Theatre Foundation, which performed in Sydney and Melbourne in 1963.

Djunmal’s paintings are held in collections throughout Australia, in Paris and Basel, and in the Kluge-Ruhe Collection at the University of Virginia.

Djunmal’s work was selected for the Scougall Collection exhibition, sponsored by Qantas, that travelled to Tokyo, Auckland, San Francisco, Montreal and Tehran in 1961–63.

Birrikitji Gumana

Dhalwaŋu clan, Yirritja moiety. About 1890–1982

Birrikitji was a ŋurrudawalaŋu – a renowned warrior – and a respected ritual and community leader.

His favourite painting subjects were the major Yirritja ancestors Barama and Lany’tjung. Birrikitji was one of the Yirritja painters of the Yirrkala Church Panels (1963).

Major exhibitions to feature his work include: Art of the Dreamtime, Tokyo, in 1966; Dreamings at the Asia Society Galleries, New York, in 1988; Spirit in Land at the National Gallery of Victoria, and Keepers of the Secrets at the Art Gallery of Western Australia, both in 1990; and Yirrkala Artists: Everywhen at the Art Gallery of Western Australia in 2009.

Gawirrin Gumana

Dhalwaŋu clan, Yirritja moiety. 1935–2016

Gawirrin, the eldest son of Birrikitji, was the oldest surviving painter of the Yirrkala Church Panels (1963).

In 2002 he won the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award. The following year he received the Order of Australia for his services to Indigenous art and was selected for the Clemenger Contemporary Art Award. In 2009 he won the Red Ochre Award.

Among the many exhibitions to feature his work are: Art of the Dreamtime, Tokyo, in 1966; Dreamings in New York in 1988; Aboriginal Art: The Continuing Tradition at the National Gallery of Australia in 1989; Yirrkala Artists: Everywhen at the Art Gallery of Western Australia in 2009; and the Biennale of Sydney in 2010.

Mithinarri Gurruwiwi

Gälpu clan, Dhuwa moiety. About 1929–1976

Mithinarri was a prolific painter. He is noted for a style of painting that features repeated motifs organised in patterns that suggest the rhythms of ritual performance.

His favourite subject was the Wäwilak Sisters and Wititj the Python in Gälpu clan territory.

Mithinarri’s paintings appear in major public collections throughout Australia, in Paris and at the University of Virginia. They have also featured in several major exhibitions, including: The Art of Aboriginal Australia, which toured North America in 1974–76; Aboriginal Art: The Continuing Tradition at the National Gallery of Australia in 1989; and Yirrkala Artists: Everywhen at the Art Gallery of Western Australia in 2009.

John Namerredje Guymala

Burdan clan, Kunwinjku language, Duwa moiety. 1926–about 1978

Namerredje was a superb draughtsman with a recognisably individual ‘hand’. The beautifully articulated patterns of rarrk that decorate his figures epitomise the Bininj notion of aesthetics in painting referred to as kabimbebme, literally ‘colour coming out’.

In 1973 Namerredje and his family moved to Yaymini outstation, far to the south of Maningrida, which they shared with Wally Mandarrk and his family. In the 1970s his work was collected by the Aboriginal Arts Board and by the American collector and professor of English literature, Ed Ruhe.

Namerredje’s paintings were selected for The Art of Aboriginal Australia, which toured North America in 1974–76; and Kunwinjku Bim at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1984.

Harry Makarrwala

Wangurri clan, Yirritja moiety. About 1880–1950s

Makarrwala was a man of great authority and influence, regarded as the headman of central Arnhem Land. By the time he met the American anthropologist W Lloyd Warner in 1926, he could speak several languages including English and Malay (Makasar). Makarrwala became the research partner and friend of Warner, who conducted fieldwork at Milingimbi and recorded an insightful personal account of the artist’s life in his ethnography A Black Civilisation.

Makarrwala’s clan lands lie further to the east, around Arnhem Bay. His paintings were collected by CP Mountford during the 1948 expedition to Arnhem Land, and by the Australian collector and philanthropist Stuart Scougall in the 1950s.

David Malangi

Manharrŋu clan, Manyarrŋu language, Dhuwa moiety. 1927–1999

Malangi was one of the great artists of his generation. He was among the first Aboriginal artists to be selected for the Sydney Biennale, in 1979 – and for Australian Perspecta, in 1983, the year he also appeared in the XVII Biennale of São Paulo, Brazil. He participated in several major international exhibitions, including: Dreamings in New York in 1988; Aratjara, which toured Europe in 1993–94; and Galerie des Cinq Continents in Paris in 1995.

Malangi was one of the driving forces behind The Aboriginal Memorial (1988) at the National Gallery of Australia. In 1996 he received an honorary doctorate from the Australian National University. The National Gallery mounted a major retrospective exhibition, No Ordinary Place: The Art of David Malangi, in 2004.

Wally Mandarrk

Barabba clan, Dangbon and Kune languages, Duwa moiety. About 1915–1987

Mandarrk was a fiercely independent traditionalist, who shunned the company of foreigners. He first met a European in 1946, while working at the sawmill at Maranboy. He was an acknowledged marrkdijbu or ‘clever man’, able to heal the sick and interact with spirit beings. Mandarrk lived in several bush camps until he established Yaymini outstation in the 1970s. His children recall the paintings he would make on their bark huts as teaching aids.

Mandarrk’s work was collected by the 1948 Arnhem Land expedition, and in the 1960s he worked with the anthropologist Eric Brandl, who documented his rock paintings. Mandarrk’s work has appeared in several major exhibitions, including Aratjara, which toured Europe in 1993–94.

Mathaman Marika

Rirratjiŋu clan, Dhuwa moiety. About 1920–1970

Mathaman was a passionate advocate of Yolŋu traditions. He inherited the leadership of the Rirratjiŋu clan when his elder brother Mawalan passed away, and led the struggle against bauxite mining in the Yirrkala region.

Mathaman became a close friend of the collector JA Davidson, his agent in the 1960s. In 1996 a painting of Mathaman’s sold for a record price for a bark painting, at an auction in New York. His work has been included in many major exhibitions, including: Australian Aboriginal Art, an Art Gallery of New South Wales exhibition that toured the country in 1960–61; Yirrkala Artists: Everywhen at the Art Gallery of Western Australia in 2009; and Yalangbara: Art of the Djang’kawu at the National Museum of Australia in 2010–11.

Mawalan Marika

Rirratjiŋu clan, Dhuwa moiety. About 1908–1967

Mawalan was a great visionary who advocated the need to teach all Australians about Yolŋu culture, especially through art. A senior Rirratjiŋu clan leader, he negotiated the establishment of the Methodist mission at Yirrkala in 1935.

Mawalan was the head of one of Australia’s great art dynasties that includes his brother Mathaman and son Wandjuk. He was a signatory to the Aboriginal Bark Petitions (1963) and the leading Dhuwa painter of the Yirrkala Church Panels (1963). In the 1960s Mawalan was the first artist to teach women (his daughters) to paint sacred clan designs. His work has been shown in many exhibitions, including: The Art of Arnhem Land, Perth, in 1957; Dreamings, New York, in 1988; Aratjara, which toured Europe in 1993–94; and Yalangbara: Art of the Djang’kawu at the National Museum of Australia in 2010–11.

Wandjuk Marika

Rirratjiŋu clan, Dhuwa moiety. About 1930–1987

Wandjuk was one of the great Yolŋu ambassadors. The eldest son of Mawalan Marika, he was taught to paint as a teenager and became a prolific artist. Disillusioned after discovering an unauthorised reproduction of one of his designs on a tea towel in 1974, he ceased painting for eight years.

He became an advocate for Indigenous artists’ rights, a founding member of the Australia Council, and chair of the Aboriginal Arts Board from 1975 to 1980. In recognition of his services to the arts, Wandjuk was awarded an Order of the British Empire in 1979, and the sculpture prize at the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards is named in his honour.

Peter Marralwanga

Kardbam clan, Kuninjku language, Yirridjdja moiety. About 1917–1987

Marralwanga’s nickname was Djakku, the Kuninjku word for ‘left-handed’. From 1949 he lived mainly in Oenpelli (Gunbalanya), before moving to Maningrida a decade later. At first he made only spears and fishnets to sell, but by 1972 he had established an outstation at Marrkolidjban which, for a time, he shared with Yirawala, who taught him the skills of painting. Marralwanga developed a personal style characterised by bold bands of rarrk in alternating colours. He also tutored a young Balang Nakurulk in bark painting.

Major group exhibitions featuring Marralwanga’s work include: Aboriginal Art at the Top, Darwin, in 1982; The Continuing Tradition at the National Gallery of Australia in 1989; Aratjara, which toured Europe in 1993–94; and Crossing Country at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2004.

Yuwunyuwun Marruwarr

Marrirn clan, Kunwinjku language, Yirridjdja moiety. 1928–1978

Yuwunyuwun was among the group of painters at Oenpelli whose work was collected by the Aboriginal Arts Board in the 1970s. He possessed a distinctive style of painting that incorporated elegant passages of rarrk and an economy of form to convey the symbolic meanings of his subjects.

His work was selected for a number of major exhibitions, including: The Art of Aboriginal Australia, which toured North America in 1974–76; Die Kunst der australischen Ureinwohner lebt at museums in Leipzig and Dresden, in the former East Germany, in 1981; and Kunwinjku Bim at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1984.

Balang Nakurulk

Kurulk clan, Kuninjku language, Duwa moiety. Born 1952

Nakurulk was a renowned international artist with several art prizes to his credit, including the 2003 Clemenger Contemporary Art Award. In 2005 he joined a handful of Australian artists to have had a retrospective exhibition in Europe, at the Museum der Kulturen in Basel. Mawurndjul designed a ceiling piece for the Musée du quai Branly, Paris, which opened in 2006.

His work featured in several major exhibitions, including: Magiciens de la Terre, Paris, in 1989; Aratjara, which toured Europe in 1993–94; World of Dreamings at the State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, in 2000; and the first National Indigenous Art Triennial, Culture Warriors, at the National Gallery of Australia in 2007.

Banapana Maymuru

Maŋgalili clan, Yirritja moiety. 1944–1982

Banapana was the son of the great Maŋgalili artist Narritjin Maymuru. Together, in 1978, they shared a creative arts fellowship at the Australian National University, the first of its kind to be offered to Aboriginal artists and which resulted in the exhibition Maŋgalili Art.

Banapana’s work was included in a number of major exhibitions, including: Aboriginal Australia, which toured Australia in 1981; Aboriginal Art at the Top, Darwin, in 1982; The Inspired Dream at Brisbane’s World Expo in 1988; and Yolngu, Aboriginal Cultures of North Australia in Brighton, England, in 1988.

Bokarra Maymuru

Maŋgalili clan, Yirritja moiety. About 1932–1981

Bokarra was the classificatory brother of Narritjin Maymuru and also a person of high ritual rank and authority. In 1963 he was among the Yolŋu group of performers in the Aboriginal Theatre Foundation, which performed in Sydney and Melbourne.

His paintings were collected by the anthropologist Helen Groger-Wurm in the mid-1960s and by American collector Ed Ruhe, whose collection now forms part of the Kluge-Ruhe Collection at the University of Virginia.

In 2009 Bokarra’s paintings in the collection of the Art Gallery of Western Australia were exhibited in Yirrkala Artists: Everywhen.

Narritjin Maymuru

Maŋgalili clan, Yirritja moiety. About 1914–1982

‘Artistfella’ is how Narritjin described himself. Not only an artist, he was also a performer, advocate, politician, clan head, ceremonial leader, philosopher and entrepreneur. Narritjin believed in the power of art to transcend cultures. In 1962, he was the instigator and one of the main painters of the Yirrkala Church Panels, and he painted the Aboriginal Bark Petitions in 1963. In 1978, he and his son Banapana were the first Aboriginal artists to be awarded a creative arts fellowship, at the Australian National University.

Before the establishment of an art centre at Yirrkala, Narritjin acted as agent to sell his own and other Maŋalili art at Djarrakpi. Narritjin’s work is in all the major public collections in Australia as well as in Paris and Basel, and at the University of Virginia. His exhibition history dates back to 1949, with Arnhem Land Art at the David Jones Art Gallery in Sydney.

His work has been selected for any major exhibitions, including: Art of Aboriginal Australia, which toured North America in 1974–76; Dreamings, New York, in 1988; The Continuing Tradition at the National Gallery of Australia in 1989; Crossroads: Towards a New Reality, Japan, in 1992; Aratjara, which toured Europe in 1993–94; and Three Creative Fellows: Sidney Nolan, Arthur Boyd, Narritjin Maymuru at the Australian National University in 2007.

George Milpurrurru

Gurrumba Gurrumba clan, Ganalbiŋu language, Yirritja moiety. 1934–1998

In 1993, Milpurrurru was the first Aboriginal artist to be given a retrospective exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia.

He was also among the first Aboriginal artists to be selected for the Biennale of Sydney, in 1979, and one of the major contributors to The Aboriginal Memorial (1988).

He participated in several major international exhibitions, including Aratjara, which toured Europe in 1993–94. He had his first solo commercial exhibition in 1985 at the Aboriginal Artists Gallery in Sydney.

In 1986 he and a group of Ganalbiŋu performed a cleansing ceremony as part of the Sydney Biennale.

Valerie Munininy

Buyuyukululmirr clan, Liya’gawumirr language, Dhuwa moiety. Born 1958

Munininy was one of the original members of Bula’bula Arts, the art centre established at Ramingining in 1990. She is one of a large number of women painters who hail from central Arnhem Land. Her traditional lands are based at Gärriyak on Galiwin’ku (Elcho Island), a coastal site associated with the Djan’kawu ancestors.

She currently lives in Ramingining and works as community library officer for the East Arnhem Shire. Although she no longer paints, she is involved in cultural education and youth programs.

Mutitjpuy Munuŋgurr

Djapu clan, Dhuwa moiety. 1932–1993

Mutitjpuy is the first bark painter to win the National Aboriginal Art Award at the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, in 1990.

He was known as a philosopher and had the authority to paint both Dhuwa and Yirritja subjects, and was the son of Woŋgu Munuŋgurr (about 1874–1958), the renowned Djapu leader and warrior.

At a young age Mutitjpuy moved to Yirrkala, where he was raised and tutored by Mawalan Marika.

He was also influenced by his father-in-law, Muŋgurrawuy Yunupiŋu, who introduced him to Yirritja law. Mutitjpuy’s paintings featured in Art of the Dreamtime at the Art Gallery of South Australia in 1974, and The Inspired Dream at the World Expo, Brisbane, in 1988.

Dick Nguleingulei Murrumurru

Bularlhdja clan, Dangbon and Kunwinjku languages, Yirridjdja moiety. About 1920–1988

Nguleingulei occasionally worked in a timber camp or as a crocodile shooter, but preferred to live in his homelands on the Liverpool River plateau. He was a magnificent draughtsman with acute powers of observation, as seen in his finely detailed drawings of animals that suggest volume and three-dimensionality.

In 1982 one of Nguleingulei’s paintings was reproduced on the 75-cent Australian stamp. His work has been selected for several major exhibitions, including: The Art of Aboriginal Australia, which toured North America in 1974–76; Kunwinjku Bim at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1984; The Art of the First Australians, Kobe, Japan, in 1986; Dreamings, New York, in 1988; and Keepers of the Secrets at the Art Gallery of Western Australia in 1990.

Bardayal Nadjamerrek

Mok clan, Kundedjnjenghmi language, Duwa moiety. About 1926–2009

Bardayal was taught the art of rock painting by his father, Yanjorluk, in the 1940s. He worked in the mining and pastoral industries, and was also known by the nickname ‘Lofty’ due to his great height.

In the late 1960s, Bardayal turned his hand to creating public paintings. In 1999 he won the Work on Paper Award at the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards. In 2004 he received the Order of Australia in recognition of his contribution to Australian culture through his art and rock art research. Bardayal was selected for the first National Indigenous Art Triennial, Culture Warriors, at the National Gallery of Australia in 2007. In the year after Bardayal passed away, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, honoured the artist with a major retrospective exhibition.

Najombolmi

Bardmardi clan, Jawoyn–Kundedjnjenghmi language, Yirridjdja moiety. About 1895–1967

Najombolmi was a renowned rock painter as well as a bark painter, and had a reputation as a great hunter and fisherman, hence his nickname Barramundi Charlie.

Najombolmi’s rock art can be seen in Kakadu National Park: his Lightning Man Namarrkon at Anbangbang near Nourlangie rock shelter, and his image of a hunter at the Djerlandjal site near Mount Brockman.

Najombolmi also restored older rock paintings, in keeping with tradition, to retain the power of the ancestors and spirits they depict.

His bark paintings were shown in Art of the Dreamtime, Tokyo, in 1966, and at the Art Gallery of South Australia in 1974.

Paddy Compass Namatbara

Alardju clan, Iwaidja language, Duwa moiety. 1890–1973

Namatbara was one of the group of artists on Minjilang (Croker Island) during the 1960s that included Yirawala, Jimmy Midjawmidjaw (1897–about 1985) and January Nangunyari Namiridali. Their work was collected by Dorothy Bennett, Karel Kupka, and Ronald and Catherine Berndt, who commissioned images of sorcery and magic. Paintings of this type had been banned by the missionaries, but they represent an important aspect of the art styles of western Arnhem Land.

Namatbara’s paintings are held in several major public collections in Australia, and in collections in Paris and Geneva, and at the University of Virginia.

January Nangunyari Namiridali

Djalama clan, Kunwinjku language, Yirridjdja moiety. About 1901–1972

Nangunyari Namiridali was one of the group of artists on Minjilang (Croker Island) during the 1960s that included Yirawala, Jimmy Midjawmidjaw (1897–about 1985) and Paddy Compass Namatbara. Their work was collected by Dorothy Bennett, Karel Kupka, Ronald and Catherine Berndt, and Louis A Allen.

Nangunyari Namiridali’s paintings are held in several major public collections in Australia, and in collections in Paris, Geneva, Basel and Los Angeles, and at the University of Virginia.

His paintings have featured in Art of the Dreamtime, Tokyo, in 1966; the Allen Collection at the de Young Museum in San Francisco in 1974; and The Continuing Tradition at the National Gallery of Australia in 1989.

Fred Didjbaralkka Narroldol

Djok clan, Kunwinjku language, Duwa moiety. About 1924–about 1980

Didjbaralkka was among the group of artists at Oenpelli (Gunbalanya) whose work was collected by the Aboriginal Arts Board in the 1970s and formed part of the exhibition Kunwinjku Bim at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1984. His paintings were also collected by the American Louis A Allen, who exhibited his collection in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s.

Didjbaralkka’s paintings were shown in the exhibition Die Kunst der australischen Ureinwohner lebt at museums in Leipzig and Dresden, in the former East Germany, in 1981. A work by Didjbaralkka was included in Aratjara, which toured Europe in 1993–94.

Bobby Barrdjaray Nganjmirra

Djalama clan, Kunwinjku language, Yirridjdja moiety. 1915–1992

Barrdjaray was the head of one of the great Australian art dynasties – the Nganjmirra family – that includes his younger brothers Jimmy Nakkurridjdjilmi and Peter (1927–1987), and their sons and grandchildren.

Barrdjaray was a prolific painter with a wide range of subjects available to him due to his high ritual status. He worked with the anthropologists Ronald and Catherine Berndt after the Second World War, and in the 1970s was a member of the Aboriginal Arts Board.

He featured in major group exhibitions, including Kunwinjku Bim at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1984, and The Continuing Tradition at the National Gallery of Australia in 1989.

Jimmy Nakkurridjdjilmi Nganjmirra

Djalama clan, Kunwinjku language, Yirridjdja moiety. About 1917–1982

Jimmy Nganjmirra was the younger brother of Bobby Barrdjaray and father of Robin (1951–1991) and Thompson (born 1954). He lived away from townships, preferring his traditional lands at Malworn and Kumarrderr.

Jimmy Nganjmirra commenced painting in the public arena in about 1960 and his work is held in several major public collections, including the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, and the National Gallery of Australia.

He was represented in Kunwinjku Bim at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1984; The Continuing Tradition at the National Gallery of Australia in 1989; and Keepers of the Secrets at the Art Gallery of Western Australia in 1990.

Jimmy Wululu

Daygurrgurr clan, Gupapuyŋu language, Yirritja moiety. 1936–2005

As a painter, Wululu was concerned with symmetry. He had worked as a builder and used a straight rule in his paintings.

Wululu was one of the major contributors to The Aboriginal Memorial (1988) at the National Gallery of Australia, and he participated in several major international exhibitions, including: Dreamings, New York, in 1988; Magiciens de la Terre, Paris, in 1989; Aratjara, which toured Europe in 1993–94; Tyerabarrbowaryaou 2, at the Biennale of Havana, Cuba, in 1994; Stories, from the Holmes à Court Collection at the Sprengel Museum, Hanover, in 1995; and Explained at the Aboriginal Art Museum, Utrecht, in 2004.

Jack Wunuwun

Gaŋarl clan, Murruŋun language, Dhuwa moiety. 1930–1991

Wunuwun was an innovative painter, unafraid to draw on influences from European art. He pioneered the rendering of three dimensions and perspective in bark painting. Wunuwun firmly believed that art was a powerful means by which to reconcile Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australia. In 1987 he was voted the Aboriginal Artist of the Year in the NAIDOC Awards.

His work was included in several major exhibitions including Artists of Arnhem Land at the Canberra School of Art in 1983; Magiciens de la Terre, Paris, in 1989; Aratjara, which toured Europe in 1993–94; and Stories, from the Holmes à Court Collection, at the Sprengel Museum, Hanover, in 1995.

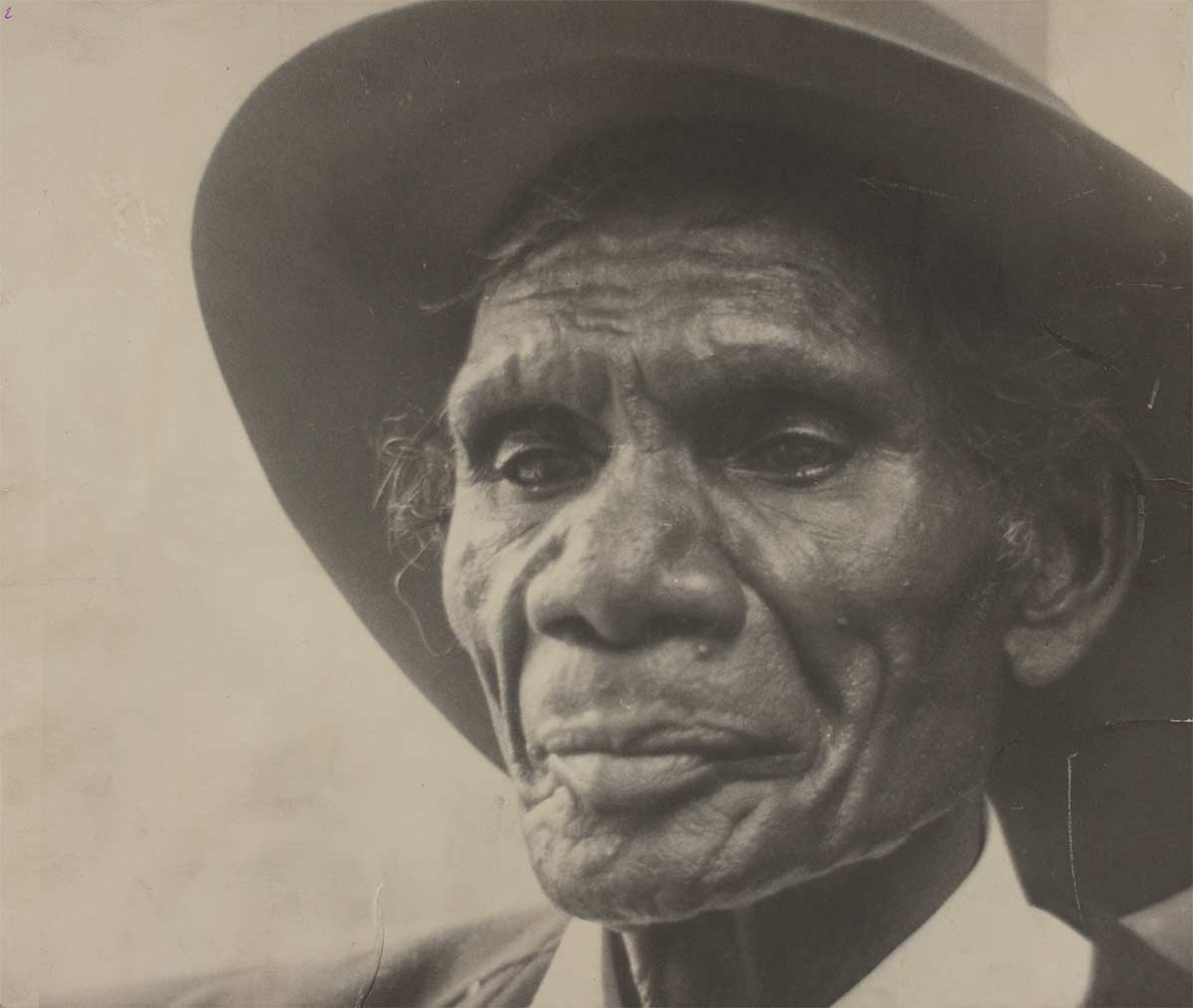

Yirawala

Born clan, Kuninjku language, Duwa moiety. About 1897–1976

Yirawala was man of high ritual status and authority. He sought to promote an appreciation of his Kuninjku culture among Europeans in order to protect Kuninjku heritage and land. He was a prolific and highly influential artist who used his ceremonial authority to introduce a number of innovations in western Arnhem Land bark painting. Chief among these was his ability to render countless variations on rarrk clan patterns to infuse his subjects with ancestral power.

Yirawala was raised in the Marrkolidjban region on the Liverpool River before moving his family to Minjilang (Croker Island), where he painted with Jimmy Midjawmidjaw (1897–about 1985), Paddy Compass Namatbara and January Nangunyari Namiridali. Here, in 1964, he met Sandra Le Brun Holmes, who was to become his patron.

Holmes organised his first solo exhibition in 1971, the year Yirawala won the International Co-operation Art Award and was appointed a Member of the British Empire for his services to Aboriginal art. In 1976 the National Gallery of Australia acquired 139 paintings by Yirawala through a program to represent Australia’s major artists in depth. Holmes made two films about Yirawala, one entitled The Picasso of Arnhem Land (1982).

Yirawala’s work has appeared in several international exhibitions, including: Dreamings at the Asia Society Galleries, New York, in 1988; and Aratjara, which toured Europe in 1993–94.

Muŋgurrawuy Yunupiŋu

Gumatj clan, Yirritja moiety. About 1905–1979

Muŋgurrawuy was a senior Gumatj cultural leader, one of the Yirritja painters of the Yirrkala Church Panels (1963) and a signatory to the Aboriginal Bark Petition presented to the Australian Government in 1963. He belongs to a family dynasty that includes his sons – the politician Galarrwuy Yunupiŋu and the recently deceased leader of the rock band Yothu Yindi – and three artist daughters.

Muŋgurrawuy’s work featured in several international exhibitions, including: Australian Aboriginal Bark Paintings 1912–1964 in Liverpool, England, in 1965; Dreamings at the Asia Society Galleries, New York, in 1988; and Aratjara, which toured Europe in 1993–94.

By Wally Caruana, an independent curator, author and consultant specialising in Indigenous Australian art. For nearly 20 years he was the senior curator of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art collections at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

A short article in The Times of London on 17 August 1948 reported on the success of a scientific expedition to Arnhem Land and alluded to a number of rock paintings by Aboriginal ‘old masters’. [1]

Under the leadership of the anthropologist Charles P Mountford, the multi-disciplined expedition collected some 600 bark paintings and sculptures, which were later distributed to Australian state art galleries and museums, and to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC. A number of these bark paintings are among the earliest works in Old Masters: Australia’s Great Bark Artists.

At the time these works were collected, anthropological interest in Aboriginal societies was growing and bark paintings were considered the quintessential form of Aboriginal art.

The first collections of bark paintings made on the basis of artistic and aesthetic merit, as opposed to ethnographic interest, were put together from 1912 by Walter Baldwin Spencer when he visited the buffalo hunting camp of Paddy Cahill at Oenpelli (now Gunbalanya) in western Arnhem Land. Spencer made several collections for the Museum of Victoria.

The artists

We know few of the names of the early painters that Spencer collected, but they would have included the fathers and uncles, brothers and cousins of a number of ‘old masters’ in this exhibition.

In this context, the term ‘old’ reflects two salient facts: these artists were born before the incursions of white settler society on their land and culture, and they carried one of the oldest continuing traditions of art known to humanity into a new era.

They experienced at firsthand the trauma of facing a foreign culture, one that was dominant and intending to settle.

Yet senior men, such as Yirawala, Mawalan Marika, Muŋgurrawuy Yunupiŋu, Narritjin Maymuru and, in later years, Gawirrin Gumana and Jack Wunuwun, demonstrated their belief that art was an eloquent and effective means of bridging the gulf that separates the two cultures. Many of these men were ritual leaders, statesmen and cultural advocates as well as artists.

Yirawala, for one, painted so that balanda (non-Indigenous people) might appreciate the profound nature of Aboriginal culture and the essential bond that people have with the land.

Many painted for land rights and human rights: in 1963 the Yirrkala Church Panels, depicting the main ancestors of the Dhuwa and Yirritja moieties, stood on either side of the altar in the local mission church, reminding Yolŋu of their ancestral birthright; in the same year, the petitions on bark, which are surrounded by clan designs, proclaimed Yolŋu’s unique relationship with the land in the face of mining; and The Aboriginal Memorial (1988) stands as a testament to the Indigenous lives lost while defending their lands since 1788.[2]

A number of the artists in this exhibition were prominent contributors to these watershed moments in the history of Arnhem Land art and in the developing relationship between Aboriginal people and balanda.

In an effort to appreciate the magnitude of the artistic achievements of these men, curators and art historians have resorted to comparisons with the elite of Western European art: Yirawala has been known as the ‘Picasso of Arnhem Land’,[3] and Jack Wunuwun, the ‘Michelangelo’.[4]

Indeed, Yirawala along with Narritjin Maymuru form the backbone of this exhibition. In their time, both these men were at the forefront of the social and cultural struggles experienced by Indigenous Australians, and were supremely gifted, innovative and influential artists whose legacies continue to this day.

Styles and techniques of painting

Broadly speaking, the art of bark painting is based on a series of unique but related visual languages. In western Arnhem Land, the connection to rock art has resulted in the predominance of figurative imagery, reliant on the artist’s draughtsmanship.

In eastern Arnhem Land, bark painters prefer geometric compositional templates with an emphasis on patterned clan designs.

In central Arnhem Land, artists tend to combine both approaches. In fact, figurative, abstracted or geometric imagery exists in all areas.

Arnhem Land paintings are characterised by the use of fine crosshatched patterns of clan designs that carry ancestral power: the crosshatched patterns, known as rarrk in the west and miny’tji in the east, produce an optical brilliance reflecting the presence of ancestral forces.

These patterns are composed of layers of fine lines, laid onto the surface of the bark using a short-handled brush of human hair, just as they are painted onto the body for ceremony.

The artist’s palette consists of red and yellow ochres of varying intensity and hues, from flat to lustrous, as well as charcoal and white clay. Pigments that were once mixed with egg yolk or orchid juice as a binder have, since the 1960s, been combined with water-soluble wood glues. Nonetheless, some artists, such as Wally Mandarrk, insist on using traditional binders.

The bark, the artist’s canvas, is stripped from Eucalyptus tetrodonta (stringybark) during the wet season, then cured over fire and flattened under weights.

Physical environment

The physical environment of Arnhem Land is diverse. In the west the rocky escarpment that extends into Kakadu National Park is home to hundreds of rock overhangs, shelters and caves bearing paintings – veritable ‘cathedrals of art’ – that date back 30 millennia. The practice of rock painting continues to this day, and Najombolmi, Bardayal Nadjemerrek and Wally Mandarrk are among a number of rock painters represented in this exhibition.

To the east, across to the Goyder and Glyde rivers, lie the savannah forests and the Arafura Wetlands of central Arnhem Land. In 1993 the pristine wilderness of the wetlands gained environmental protection through World Heritage Listing based on its unique ecology and its cultural value to the Ganalbiŋu and related groups in the area.

From here, chains of islands lead to the eastern coast of Arnhem Land and south to Blue Mud Bay, where the full metaphorical and physical forces of fresh water meeting salt water are evident in the landscape and out to sea, and are played out on bark.

Societies

Despite the variety of languages and dialects spoken across Arnhem Land, clans in the region share much in the way of connections to ancestors, belief systems, ritual practices, exchange ceremonies and social structures.

The peoples of the west are known by the collective term Bininj, while those in central and eastern regions refer to themselves as Yolŋu. The exhibition follows this distinction, with the main artists, Yirawala and Narritjin, belonging to the Bininj and Yolŋu groups respectively.

Arnhem Land societies are complex in their structures, but fundamentally they are divided into two halves, known by the word ‘moiety’, an anthropological term derived from the French moitié (half). In eastern and central Arnhem Land the moieties are called Dhuwa and Yirritja, and Duwa and Yirridjdja in the west.

Every person, clan and animate or inanimate thing – whether an ancestor, animal, feature of the landscape or natural phenomenon – belongs to one moiety or the other. Ownership of land, ceremonies and painted designs is inherited from one’s father, while custodial or managerial rights are inherited from one’s mother.

A person must marry someone of the opposite moiety, and people belonging to each moiety play different but complementary roles in ceremonies.

A number of sections in Old Masters have been organised according to the artists’ or subject’s moiety affiliation, and the introductory work, The Djan’kawu Cross Back to the Mainland (right), by Djunmal, features designs belonging to both moieties.

Missions and townships

In 1931 the Australian Government declared Arnhem Land an Aboriginal reserve. This was an era when it was believed the Aboriginal race was inferior and would soon disappear. All the bureaucracy could hope to do was ‘smooth the pillow of a dying race’.[5]

Mission stations had been set up across the region: from Paddy Cahill’s buffalo hunting camp at Oenpelli, which became a mission in 1916, to the missions established at Milingimbi in 1923, Yirrkala in 1935, Minjilang (Croker Island) in 1940, and Galiwin’ku (Elcho Island) in 1942. Maningrida was set up as a trading post in 1947, and the township of Ramingining was built in the early 1970s.

With the introduction of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act in 1976, there was a movement away from these main townships. Today, many people live in smaller communities on their traditional lands, which are referred to as homelands or outstations.

The collectors

Mountford’s 1948 expedition to Arnhem Land visited Oenpelli, Yirrkala and Groote Eylandt.[6] The National Museum of Australia’s vast holdings of bark paintings from Arnhem Land include substantial numbers of works that were gathered by the collectors who came after Mountford. Dorothy Bennett accompanied Tony Tuckson and Stuart Scougall in the late 1950s on their pioneering collecting trips on behalf of the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Bennett struck out on her own and, as with all of these collectors, forged close links with the artists, especially around Oenpelli and Minjilang. Karel Kupka, the Czech–French artist and ethnographer, first visited Australia in 1951 with the express purpose of collecting on behalf of European museums. He was one of the first to describe bark paintings in artistic and aesthetic terms.[7]

In fact, anthropologists and ethnographers were the first to record the ‘art history’ of Aboriginal art. Helen Groger-Wurm, an Austrian scholar who collected on behalf of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies,[8] was privileged by the trust that Yolŋu artists placed in her,[9] and Sandra Le Brun Holmes became the patron of Yirawala.[10]

JA (Jim) Davidson, a passionate supporter of the art and artists of Arnhem Land, became a close friend of Mathaman Marika, among others.[11] These are some of the collectors whose efforts, enthusiasm and passion created the great collections from which the Old Masters exhibition is drawn.

Notes

1 Anonymous, ‘Rich finds of Arnhem Land Expedition’, The Times, 17 August 1948, p. 3.

2 The Aboriginal Memorial (1988) now stands at the entrance to the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

3 Yirawala: Picasso of Arnhem Land is the title of a film by Sandra Le Brun Holmes (Morning Star Productions, Sydney, 1982)

4 James Mollison, the founding director of the National Gallery of Australia, quoted in P Ward, ‘The Michelangelo of Arnhem Land’, The Australian, 12–13 September 1987, supplement, p. 3.

5 A phrase that was first used by anthropologist Daisy Bates in her memoir, The Passing of the Aborigines: A Lifetime Spent Among the Natives of Australia, Murray, London, 1938.

6 CP Mountford (ed.), Records of the American–Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land, vol. 1: Art, Myth and Symbolism, Melbourne University Press, 1956.

7 K Kupka, Un art a l’état brut, La Guilde du Livre, Lausanne, 1962; K Kupka, Dawn of Art, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1965.

8 Now the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) in Canberra

9 H Groger-Wurm, Australian Aboriginal Bark Paintings and their Mythological Interpretation, vol. 1: Eastern Arnhem Land, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1973.

10 S Le Brun Holmes, Yirawala: Painter of the Dreaming, Hodder and Stoughton, Sydney, 1992.

11 JA Davidson, ‘Mathaman: Warrior, artist, songman’, Art Bulletin of Victoria, no. 29, pp. 4–23.

- Last updated: 5 June 2014

- 3 programs

Old Masters spans a critical period in the history of the art of Arnhem Land and its peoples, from 1948 to 1988.

The Second World War is a significant historical marker for the people of Arnhem Land, due to the bombing of Darwin and parts of the northern coast of the region.

Anthropologists arrived after the war, and were followed by the collectors, both private and public, to see at firsthand the art of Arnhem Land, and to meet its creators and collect their work. They took their art to new audiences, in Australia and abroad.

The National Museum of Australia opened to the public in 2001. By and large its collections have been confined to storage, and many of the artists have been little-known outside their communities.

Nonetheless, over the past decades the old masters in this exhibition have attracted the attention of the art world and the public at large; and recent generations of Arnhem Land bark painters continue to build on their artistic heritage, taking their art in new directions while building on past achievements.

Old Masters is a small taste of the Museum’s collection of bark paintings; it is but a sample of the richness, diversity and complexity of Indigenous cultures across Australia. Through this exhibition, the Museum encourages all Australians to share in the history and culture of Indigenous Australians.

Identity

The expression of identity is a recurring theme in bark painting. It personalises the subject of a painting to allow the viewer to see ‘through the artist’s eyes’.

Identity is defined by a person’s family ties, clan membership, descent from a particular ancestor, attachment to country, and social and ritual status. It is expressed in painting through the same patterns of clan designs that are painted onto a person’s body in ceremony.

These designs also show the moiety to which the artist belongs. Djunmal’s painting The Djan’kawu Cross Back to the Mainland symbolises the complementary roles played by the moieties.

The design on the right shows the Djan’kawu ancestors associated with the artist’s Dhuwa moiety. It represents the paths they travelled as they created the first peoples and the freshwater wells (the circles in the painting).

The Yirritja moiety design on the left represents mangrove worms in the brackish waters where fresh water meets salt water.

Arnhem Land

Arnhem Land lies in the subtropical north of the Australian continent. The physical environment varies from the rocky escarpment in the west, extending into Kakadu National Park. To the east lie the savannah forests and the Arafura Wetlands of central Arnhem Land. Chains of islands lead to the eastern coast of Arnhem Land and south to Blue Mud Bay.

From 1916 to the 1970s, missions and settlements were established throughout the region. In 1931 the Australian Government declared Arnhem Land an Aboriginal Reserve, and with the introduction of land rights in 1976 many Aboriginal people returned to live on outstations on their traditional lands. The settlements continue to provide resources, including art centres for the outstations.

Pronunciation and spelling

The peoples of western Arnhem Land refer to themselves collectively as Bininj, and those in central and eastern Arnhem Land as Yolŋu. Their languages have special sounds, which are represented in this website and the catalogue in written form using a particular set of characters and symbols, or diacritics. These sounds are pronounced as follows:

galpu (spear-thrower): garl – pu

Gälpu (clan name): Gaal – pu

Yolŋu (the people): Yuul – ngu (‘ng’ as in ‘sing’)

Ngalyod (the ancestor): Ngal – yod (‘Ng’ as in ‘sing’)

Djan’kawu (the ancestors): Jahn – kawu`

There are regional differences in spelling. For example, the moieties (the basic social divisions) in western Arnhem Land are Duwa and Yirridjdja, and in eastern Arnhem Land, Dhuwa and Yirritja. Similarly, the ancestors known as the Wägilak Sisters in central Arnhem Land are the Wäwilak Sisters in the east.

The exhibition Old Masters: Australia's Great Bark Artists was on show at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra from 6 December 2013 to 20 July 2014.

The international version of Old Masters, supported by the Australian Government through the Australia–China Council of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, was on show at:

- National Taiwan Museum, 4 October 2019 to 9 February 2020

- Sichuan Museum, 26 June to 25 August 2019

- Shenzhen Museum, 13 April to 26 May 2019

- Shanghai Natural History Museum, 15 November 2018 to 6 January 2019

- National Museum of China, Beijing, 4 July to 2 September 2018

All these bark paintings are part of the National Museum of Australia’s collection. © the artist or the artist’s estate, licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency 2013, unless otherwise specified. These images must not be reproduced in any form without permission.