On behalf of our ancestors

Statement recognising the traditional ownership of Dja Dja Wurrung people over their country, 15 November 2013:

All natural places within Dja Dja Wurrung country were well known, had a name and song and were celebrated as a part of country and culture.

When settlers arrived in Victoria, the world of Dja Dja Wurrung people was fractured. In 1849, Scottish-born John Hunter Kerr and his business partner established the Fernyhurst property on a lease of about 36,000 hectares in Dja Dja Wurrung country.

Kerr was sympathetic to Dja Dja Wurrung people, who continued to live and hunt on their land and camped close to Kerr’s station hut. Kerr photographed them and their ceremonies, and collected a number of their objects.

These objects have since become the subject of legal action over where they belong. In 2004, when they were on loan to Museum Victoria, Dja Dja Wurrung representatives unsuccessfully sought to stop some of them, including this bark etching (opposite), from being returned to London.

Aunty Fay Carter, Dja Dja Wurrung elder, 2014:

I’d like the rest of the world to know that Dja Dja Wurrung still exist. We are still here as a people. We are proud and value our culture. We honour our ancestors, and everything that we do, we are doing on behalf of our ancestors, who didn’t have the voice that we have today.

Old objects

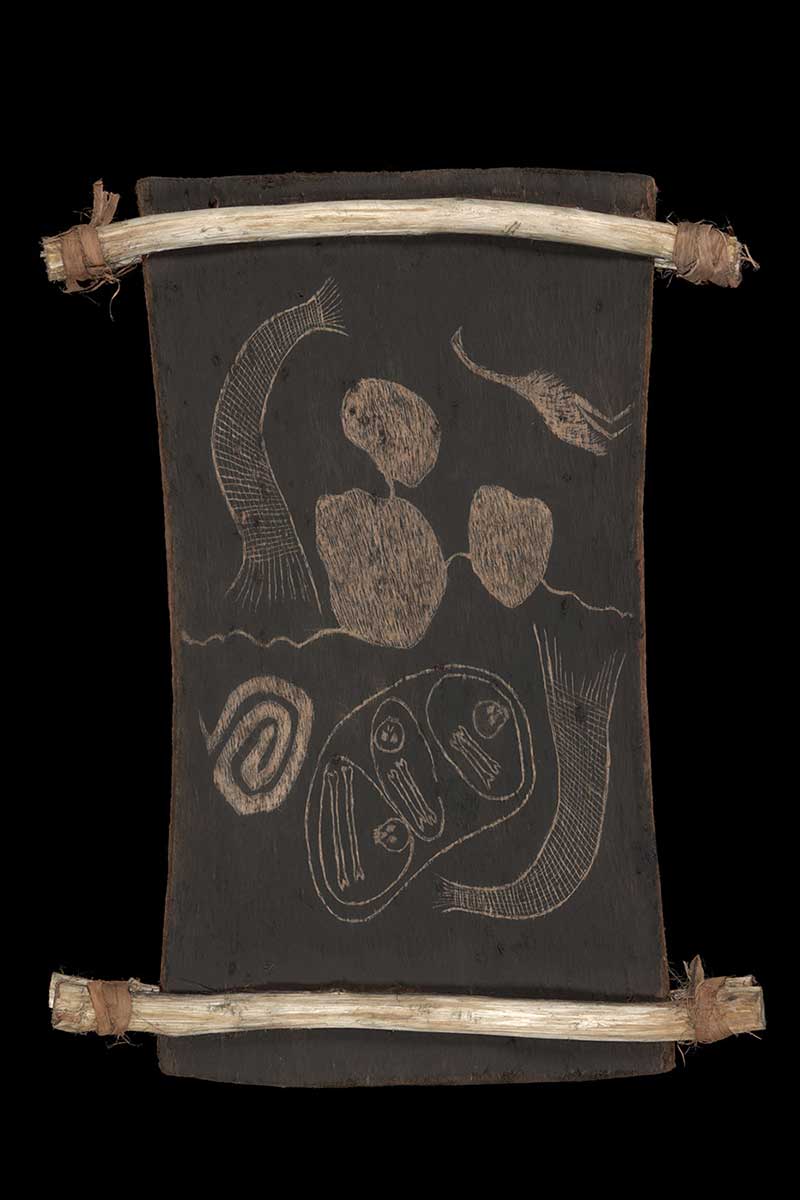

John Hunter Kerr collected this bark etching at Fernyhurst, near Boort, in Victoria.

It was among Dja Dja Wurrung material that Kerr entered in a sequence of local and colonial exhibitions, leading up to its display at the 1855 Exposition Universelle in Paris.

In 1857 some of these objects were given to the Kew Royal Botanic Gardens Museum of Economic Botany. From here, the bark entered the Christy collection, before it was formally transferred to the British Museum.

In 2004 it was included in Museum Victoria’s Etched on Bark 1854: Kulin Barks from Northern Victoria exhibition.

It returned to London after unsuccessful legal attempts to keep it in Australia.

New objects

Back in Country, 2015

Jida Gulpilil, Dja Dja Wurrung, 2015:

Doing this bark is not just about making an etching and having something physical to show. It’s a lot more than that … [It’s] to send a message. To show people who we are, how we’re connected to country – our spiritual and physical connection.

Barramul (emu feather dance skirt), 2014

Wendy Berick, Dja Dja Wurrung, 2015:

We are still practising culture and it is important we make a strong visual impression on the wider Australian communities. They like to think we [are] not here. They like to think that history is disconnected from people today. It’s not. It’s right here, ’cos we’re right here.

You may also like