The village of Collingullie lies in southern New South Wales, close to the Murrumbidgee River, surrounded by productive farming and grazing country. Each year thousands of people in Australia and across the world consume a range of different foods grown in Collingullie paddocks, including wheat, oats, triticale, canola, lamb and beef.

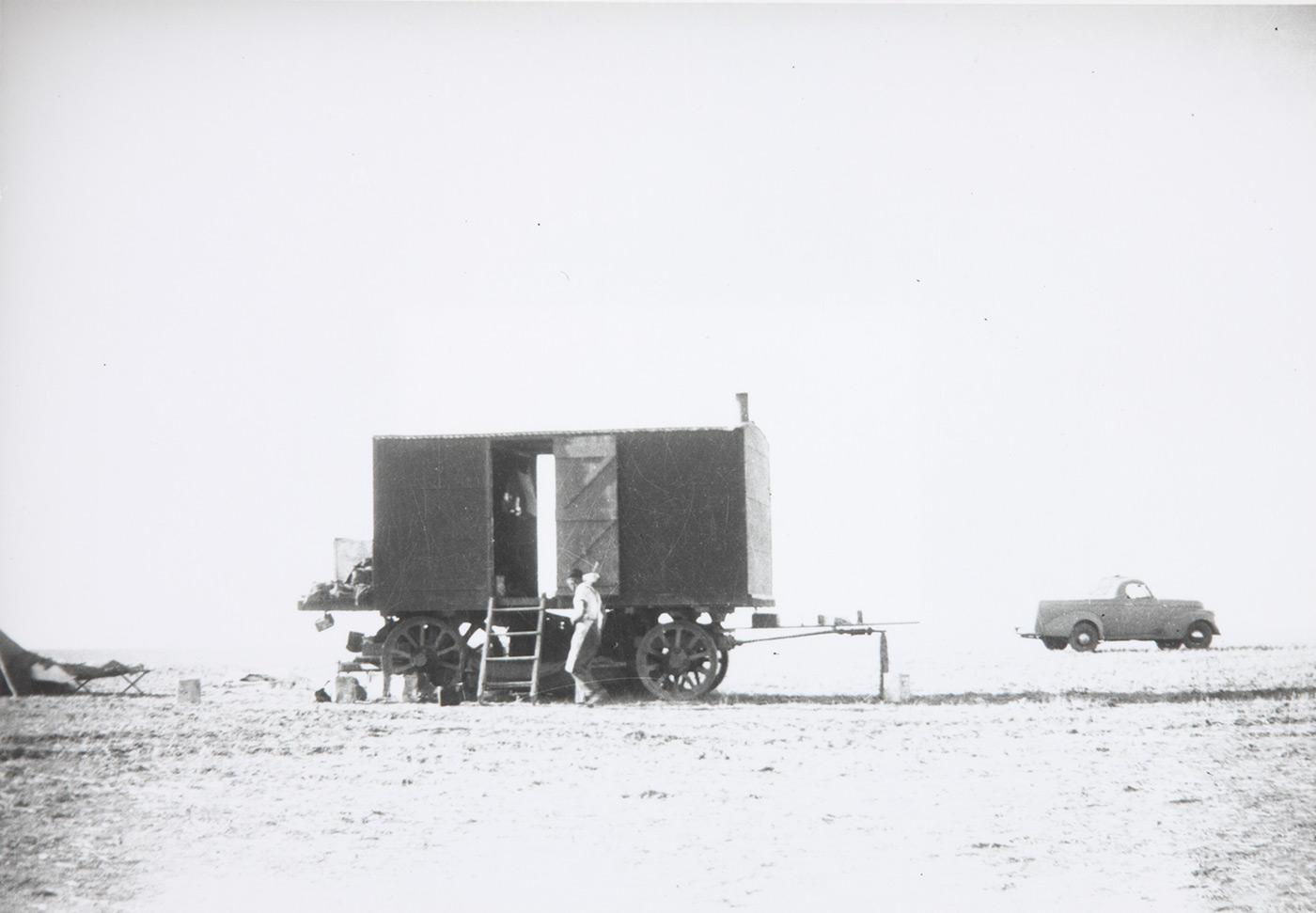

Fife Bros cook’s galley

The long established significance of agriculture to the Collingullie area is recorded in the corrugated iron, timber and steel of a cook's galley – or mobile kitchen – which is part of the National Museum of Australia’s collection.

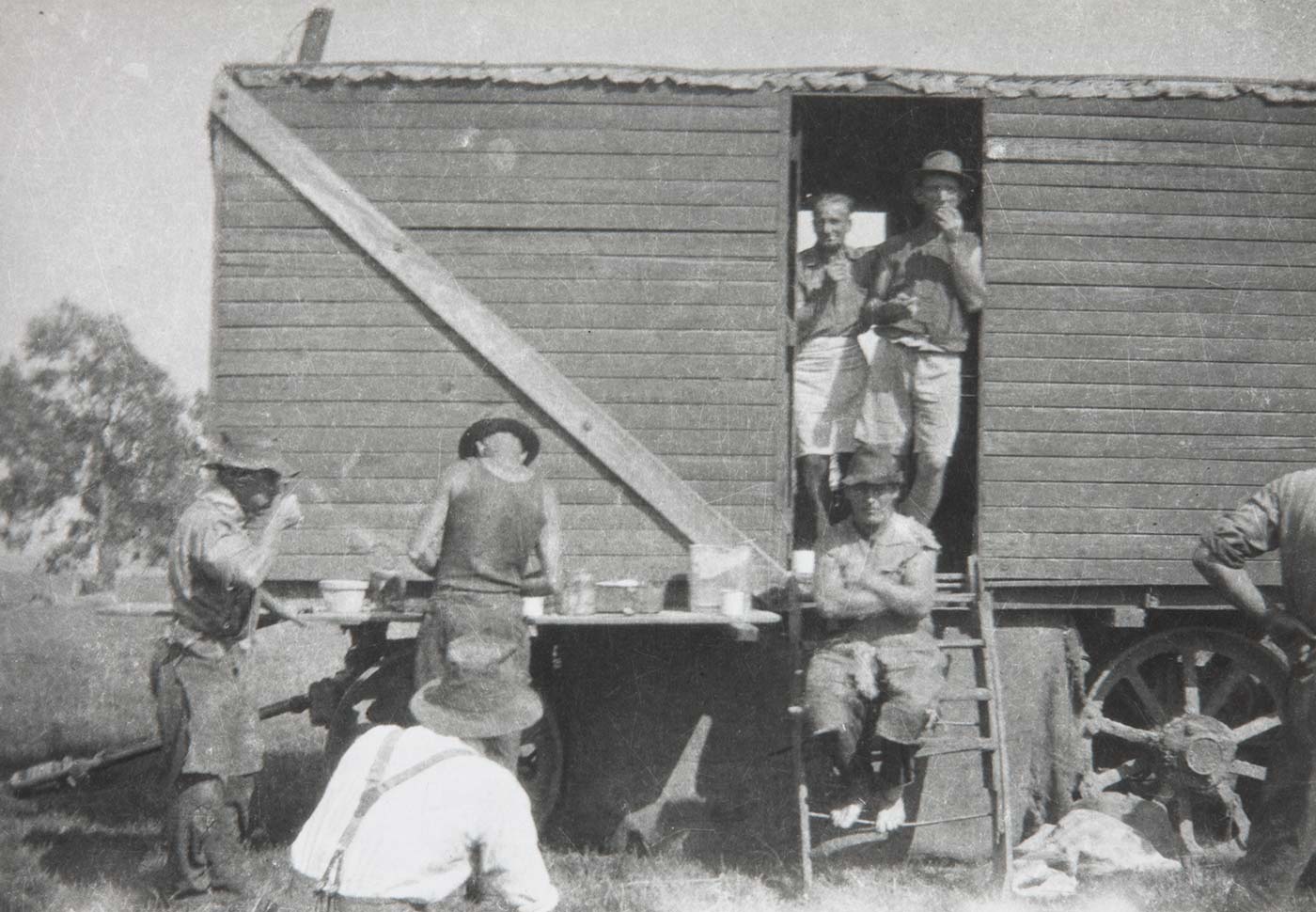

Fife Bros chaffcutting team

The cook's galley was donated to the National Museum in 2011 by former parliamentarian Wal Fife, whose family operated two chaffcutting teams throughout the Riverina region during the 1930s and 1940s. The Fife family had earlier donated a galley that belonged with the other chaffcutting plant to the Museum of the Riverina in Wagga Wagga.

Each team operated a steam-powered chaffcutter that chopped locally grown oaten hay into food for draught horses. Before tractors and diesel, farming in the Collingullie district and beyond relied on horses and chaff. Fuelling the chaff cutters were hot meals prepared on the wood-fired stove inside the cook’s galley.

1950s home movies

Ron Lashbrook grew up on Longfield, a wheat and sheep farm southwest of Collingullie.

In the early 1950s Ron’s parents gave him a home movie camera for his birthday. The films below show a prosperous and populous farming community.

During his life as a farmer, Ron witnessed dramatic technological and social changes.

Tractors replaced teams of sturdy draught horses, and the emergence of high-input farming systems drove the expansion of farm sizes and rural depopulation.

On the farm

In 1939 the Lashbrook family replaced their Clydesdale horse team with a new tractor. No longer did they need to grow hay and cut chaff to feed the hard working animals. They turned more country to crop, and used the extra income to buy diesel.

Family life revolved around farming tasks like hay making, harvesting crops and marking lambs. Chris Lashbrook, Ron’s son, raised pigs on Longfield.

Community tennis courts

In the 1950s Ron Lashbrook captured images of large tennis parties at Collingullie and nearby Belfrayden. He built play equipment at the Collingullie recreation ground for the area’s many children. The bustling village held dances in the community hall on Friday nights.

In later decades a relentless economic dynamic of ever increasing farm sizes and the use of ever larger machines drew people away from the farmlands of southern Australia. Today the once raucous tennis courts at Belfrayden have vanished beneath the grasses of a quiet paddock.

Murrumbidgee River

On the edge of the Murrumbidgee floodplain, Collingullie is a watery place. Wiradjuri people tended a range of food species in local channels and billabongs, including fish, waterbirds, yabbies, turtles and mussels.

In the 1950s the Lashbrook family picnicked each Sunday at a waterhole on Old Man Creek, which winds across the floodplain west of Collingullie. During summer, the children swam. In the winter of 1956, an especially wet year, Ron Lashbrook captured unique footage of sweeping Murrumbidgee floodwaters.

Wiradjuri people

Before the emergence of horse and chaff driven pastoral and agricultural enterprises across the Riverina region, the gentle slopes and Murrumbidgee River plains of the Collingullie district nourished generations of the local Wiradjuri people.

Tubers of murnong, the native yam daisy (Microseris lanceolata) were probably a staple food, as the local property name ‘Arajoel’ is recorded to mean ‘yams on the plain’ or ‘pretty plain’, suggesting an expanse of many bright yellow yam flowers and a diversity of other grassland blossoms, like billy buttons and chocolate and vanilla lilies.

Changing floodplains

A wide flood plain separates Collingullie village from the Murrumbidgee River. Since the construction of Burrinjuck Dam and other reservoirs in the upper reaches of the Murrumbidgee during the 20th century, Collingullie floodplains have rarely carried water.

Wiradjuri knew different, watery terrain. In the nearby town of Wagga, the Museum of the Riverina holds a canoe tree removed from a Collingullie paddock, and fishing spears from Ganmain station, on the other side of the river.

In 1925 a reporter from the Gundagai Independent interviewed a well-known Wiradjuri elder, commonly known as ‘Marvellous’.

The elder had grown up alongside the Muttama Creek, a Murrumbidgee tributary northeast of Collingullie, in the early years of colonisation. He remembered an abundance of Indigenous foods, and described lifeways that were probably replicated in the nearby area now called Collingullie:

The Muttama Creek, in his boyhood days, was full of fish. The women of the tribe were fish catchers — they used to capture as many as they wanted with the aid of spears … In those days there were plenty to eat — plenty of possum and fish, and fields of yams.

European settlement

Wiradjuri people in the Collingullie area resisted the taking of their bountiful country for pastoralism. The original name of Collingullie village was Mundowy. Ewen and Duncan Cameron established Mundowy station in the late 1850s.

‘Ewen and Duncan had several encounters with Aborigines,’ wrote a Collingullie historian in 1975, ‘[b]ut only one serious encounter, when they had to open fire with guns.’

The newcomers had difficulty maintaining dining habits acquired elsewhere. When Alexander and Anne Davidson established Bullenbong station in 1843, the nearest store was at Tarcutta, a three-day round trip to the east.

They made the journey every three months, with a packhorse to haul back supplies. Wheat crops sown into fertile Bullenbong soils provided grain to grind into flour using a hand operated mill.

Chinese market gardeners supplied produce to many in the Collingullie district. Alice Bolger grew up on Toronto, a pastoral station south of Collingullie, early in the twentieth century. Her father James leased a large area beside the creek to a Chinese man, George Pugh. Alice recorded her memories of George and his garden in 1975:

[H]e was a most industrious gardener — it was a model garden, just like a patchwork quilt. My father used to call it ‘the Garden of Eden’, which in fact it really was. I can still see it in my mind’s eye. If I remember rightly the arrangement was that the Chinaman did not pay Dad any rent, however in return he supplied us with all the vegetables and fruit we needed for the home, as it comprised a lovely orchards as well … he had a great big van and he used to travel around the district in it selling his vegetables and fruit.’

Collingullie Public School

Collingullie Public School is a small rural school 24 kilometres west of Wagga Wagga. In 2011 the school had an enrolment of around 30 students. Students at the school come from the local village and from farms in the outlying area. Collingullie Public School is a member of the Wagga Wagga Smalls Schools Network and prides itself on the partnerships it has with these other small schools.

References

'Aboriginal Pioneer’, The Burrowa News, 14 August 1925.

Back to Collingullie, p. 2.

Collingullie Celebrations Committee, Back to Collingullie, Collingullie, 1975, p. 4.

Letter from Alice Bolger to Ian Vennell, 20 September 1975.

Wiradjuri Heritage Study, Wagga Wagga City Council, November 2002, p. 48 and 58.