The Yolŋu-speaking artists of the region are renowned for their engagement with the wider community.

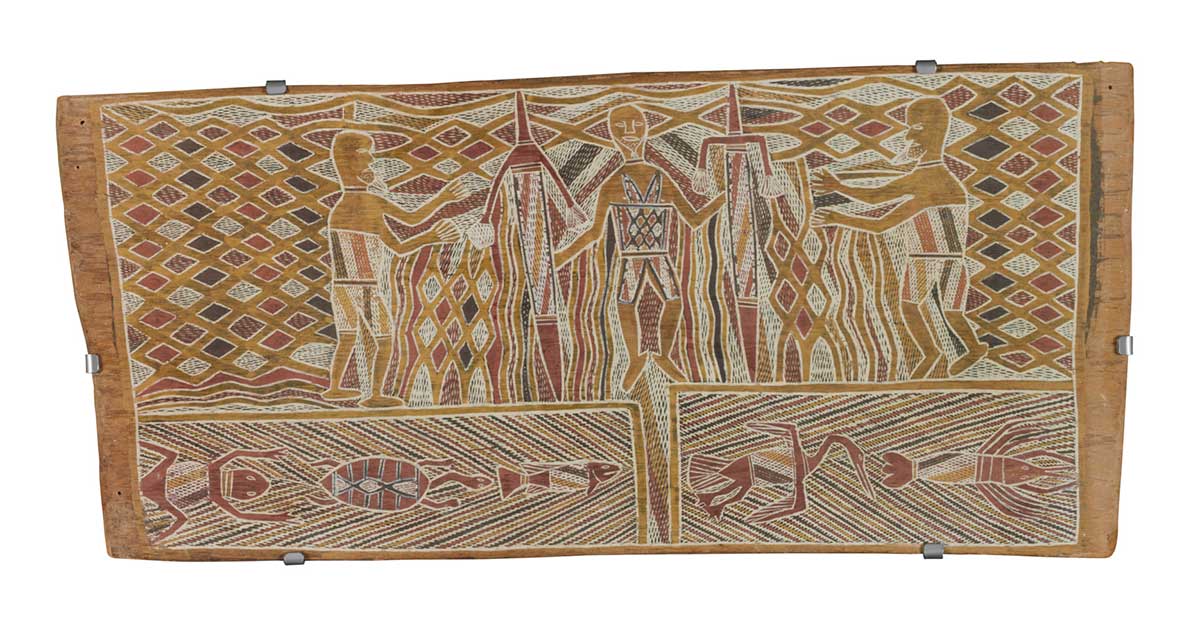

In the early 1960s many of the artists shown here collaborated in painting the monumental Yirrkala Church Panels, which were placed either side of the altar of the local mission church as an act of affirmation of traditional culture.

They also painted the Bark Petitions that were presented to Parliament as deeds of title to their land in the first Land Rights case 50 years ago. Narritjin Maymuru was one of the chief protagonists in both events and is the focus of this section.

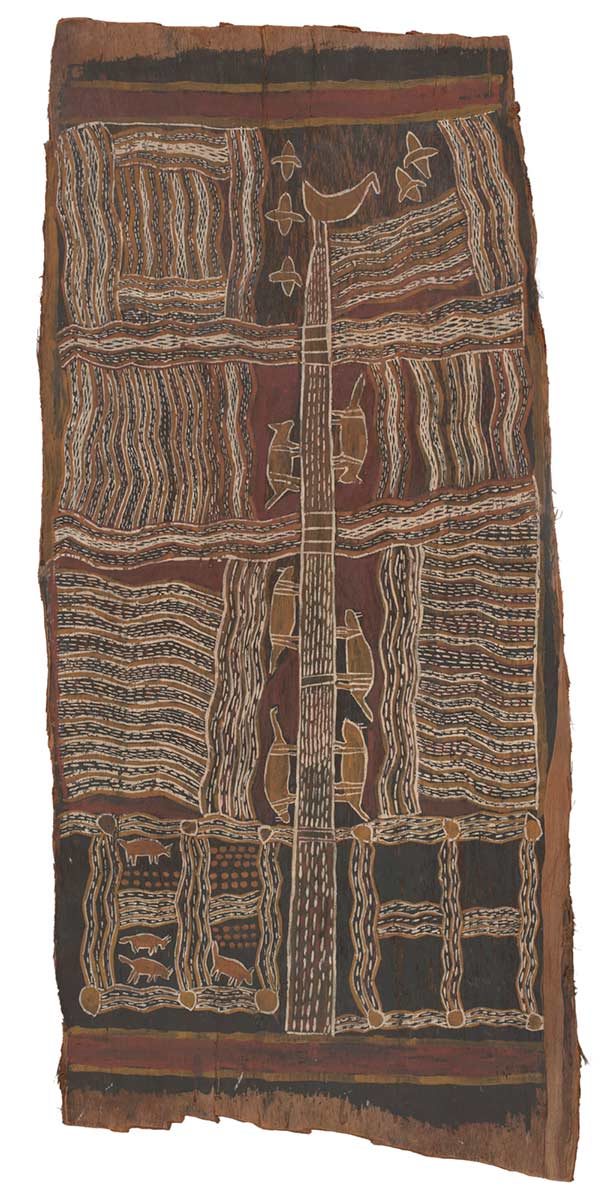

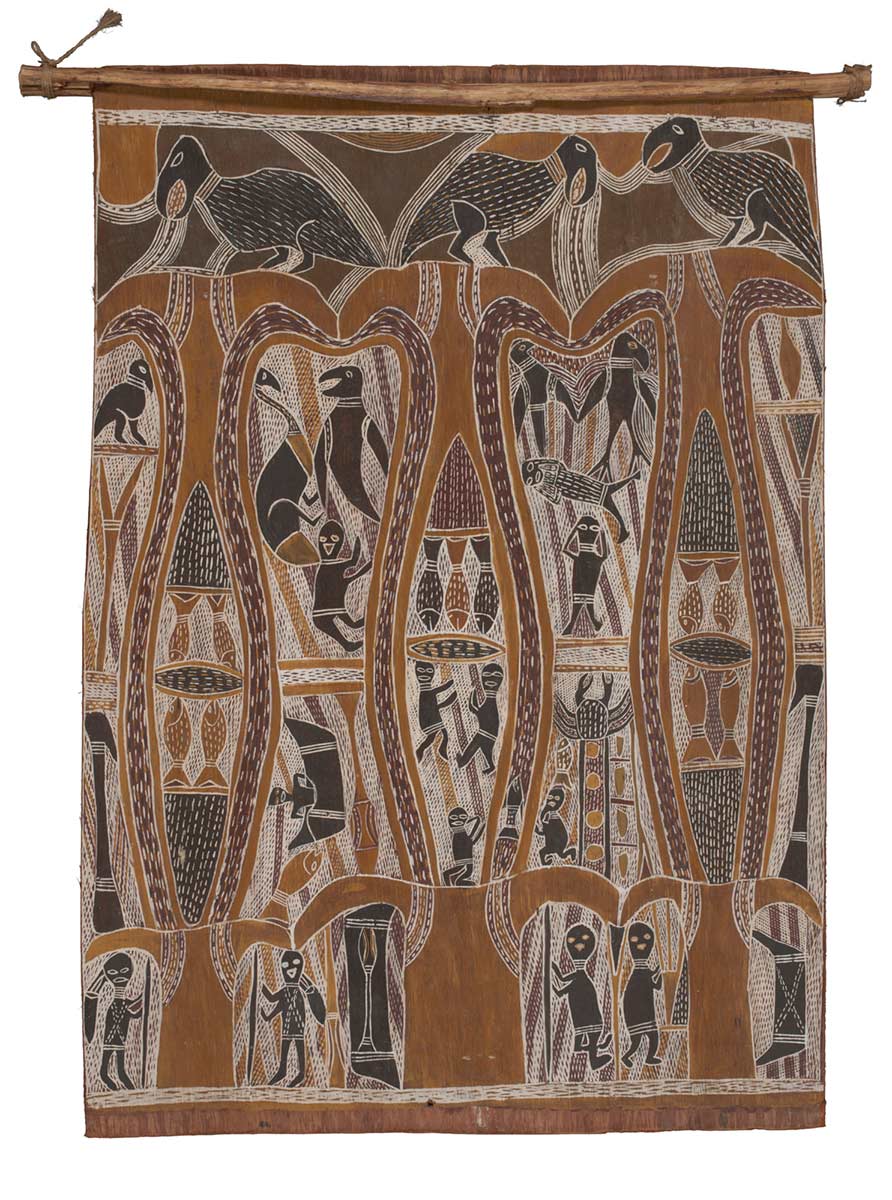

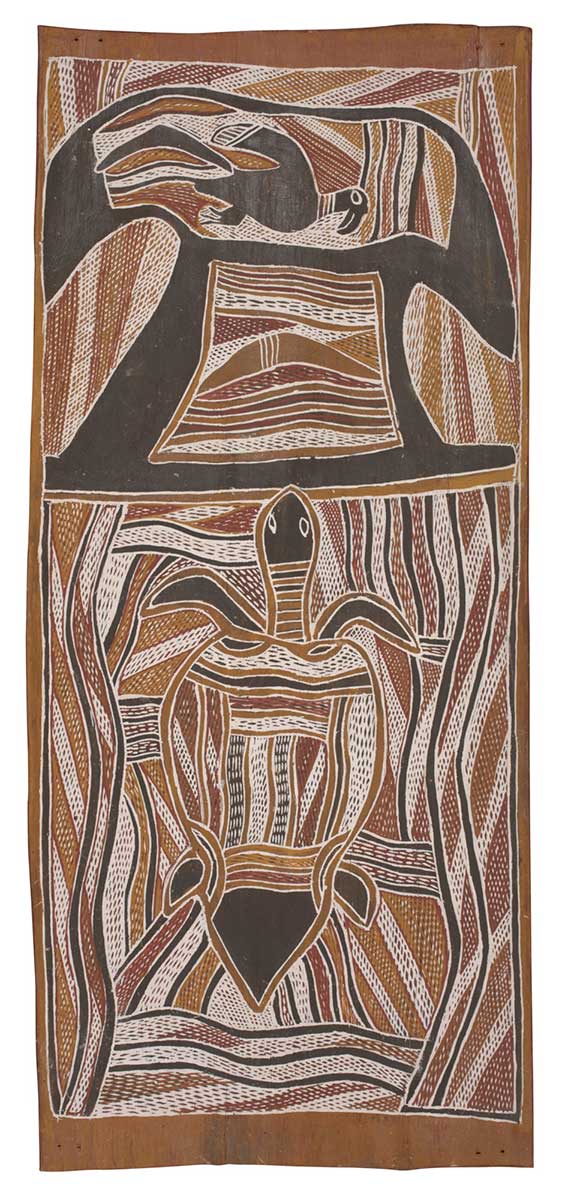

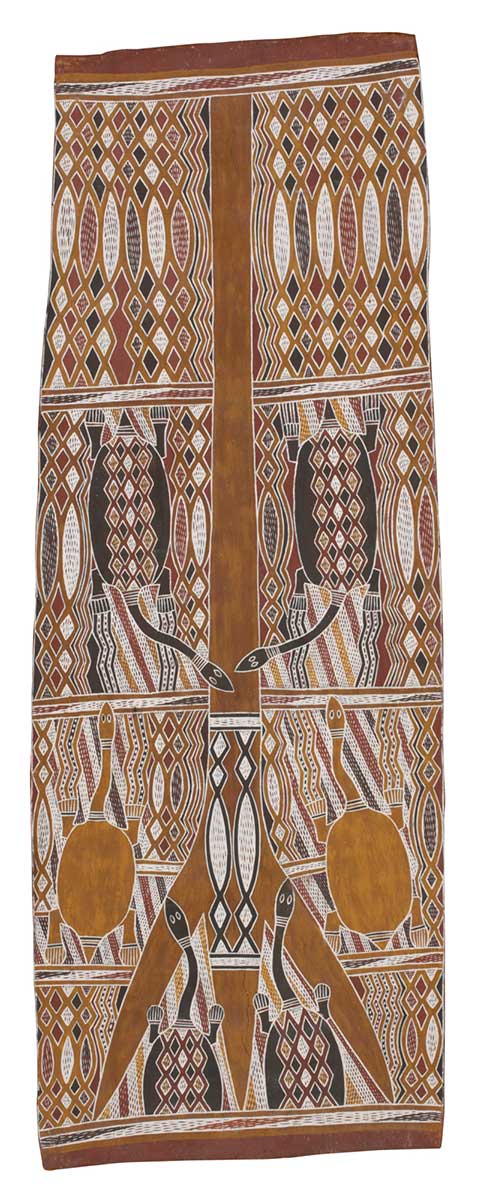

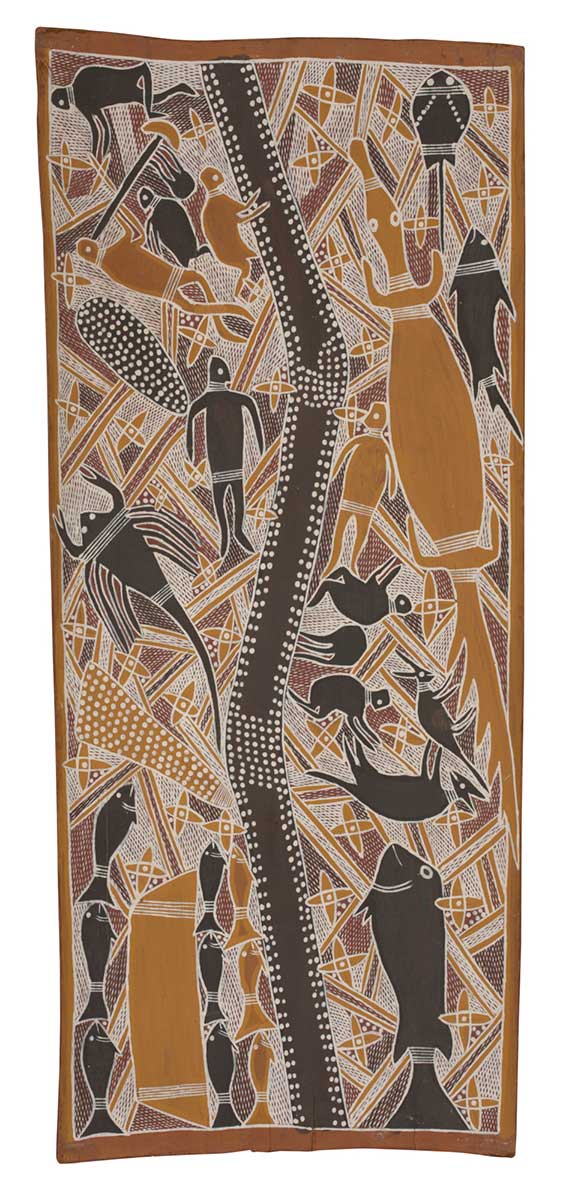

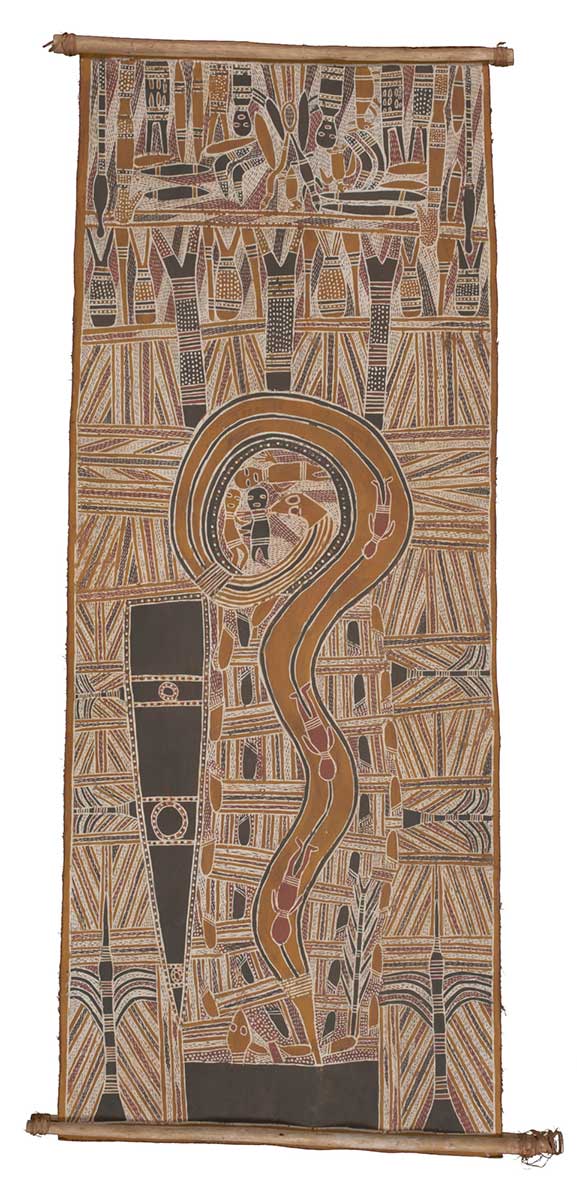

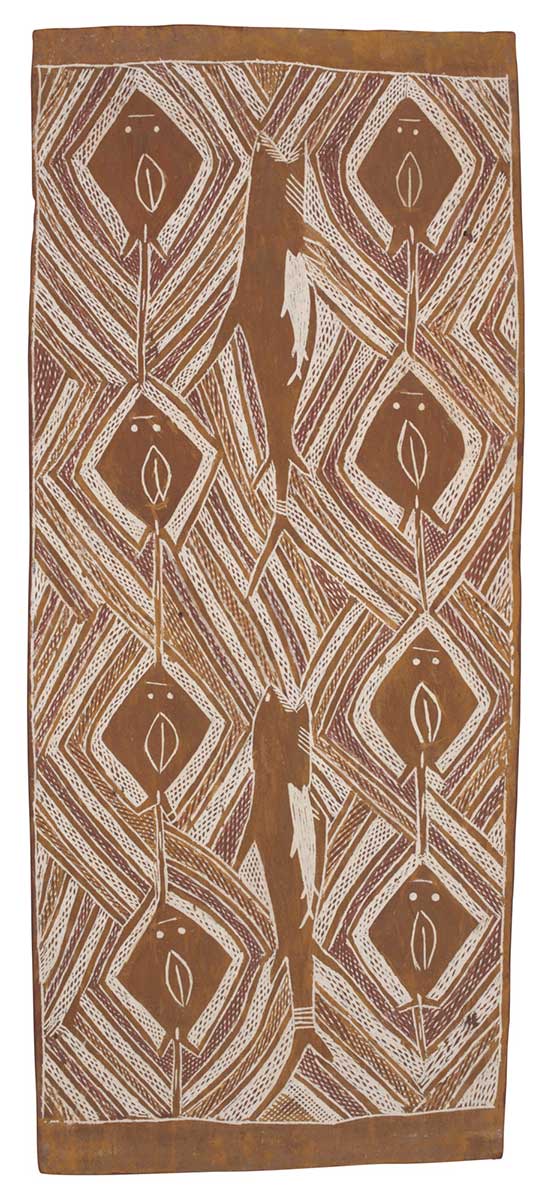

Narritjin Maymuru was a ceremonial leader of the Yirritja moiety and Maŋgalili clan, and a highly influential artist. The main theme in his paintings concerns two ancestral women, the Nyapililŋu (also known as Wurrathithi), who mourn the death of their brother, Guwak the Koel Cuckoo, at the salt lake of Djarrakpi on Cape Shield.

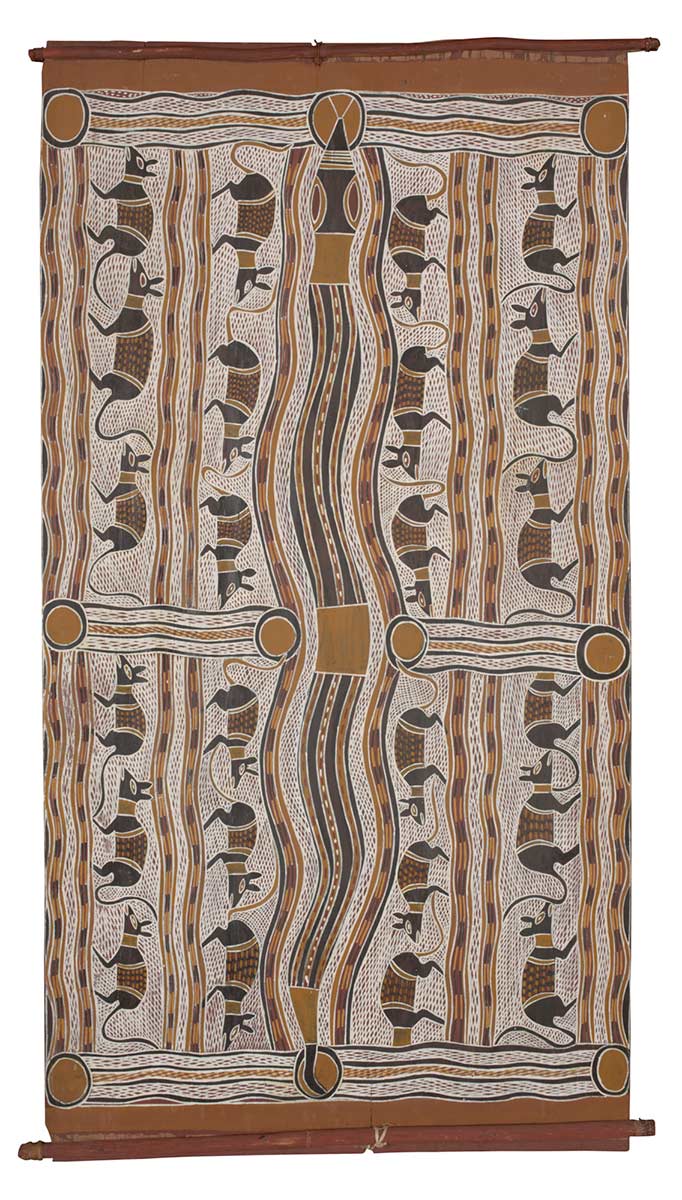

The Nyapililŋu are often represented by their digging sticks, wooden bowls and X-shaped breast girdles, rather than being drawn figuratively. The women are accompanied by Marrŋu the Possums, who run up and down the marrawili (native cashew or casuarina trees) spinning fur into string to create the sand dunes at Djarrakpi.

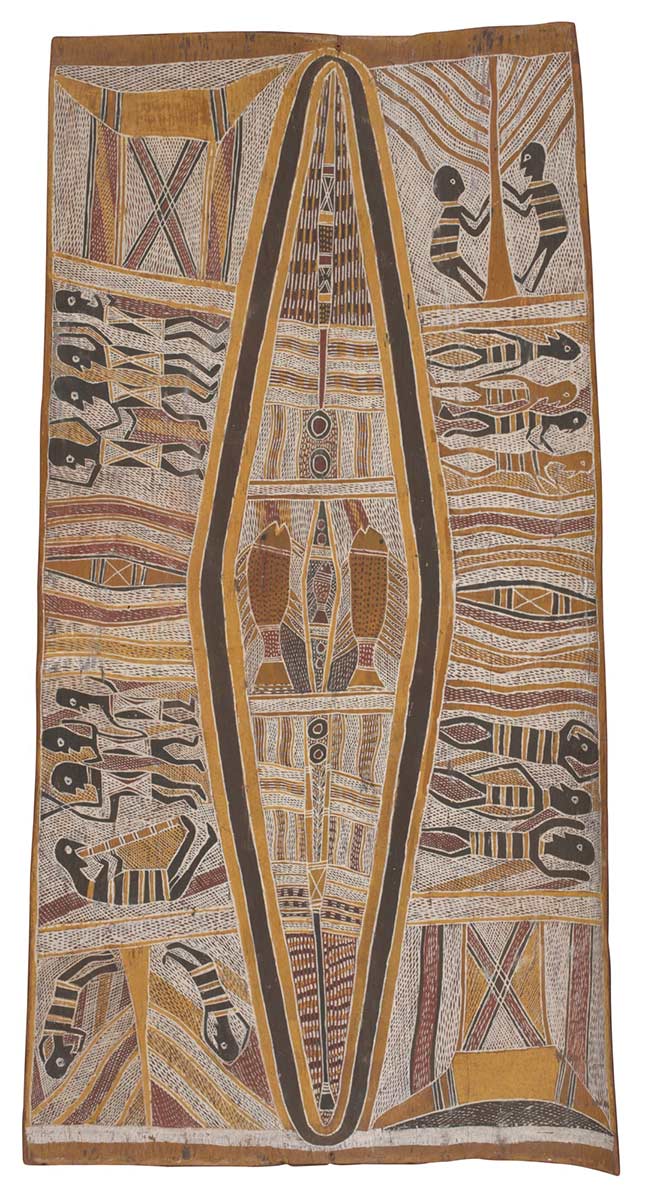

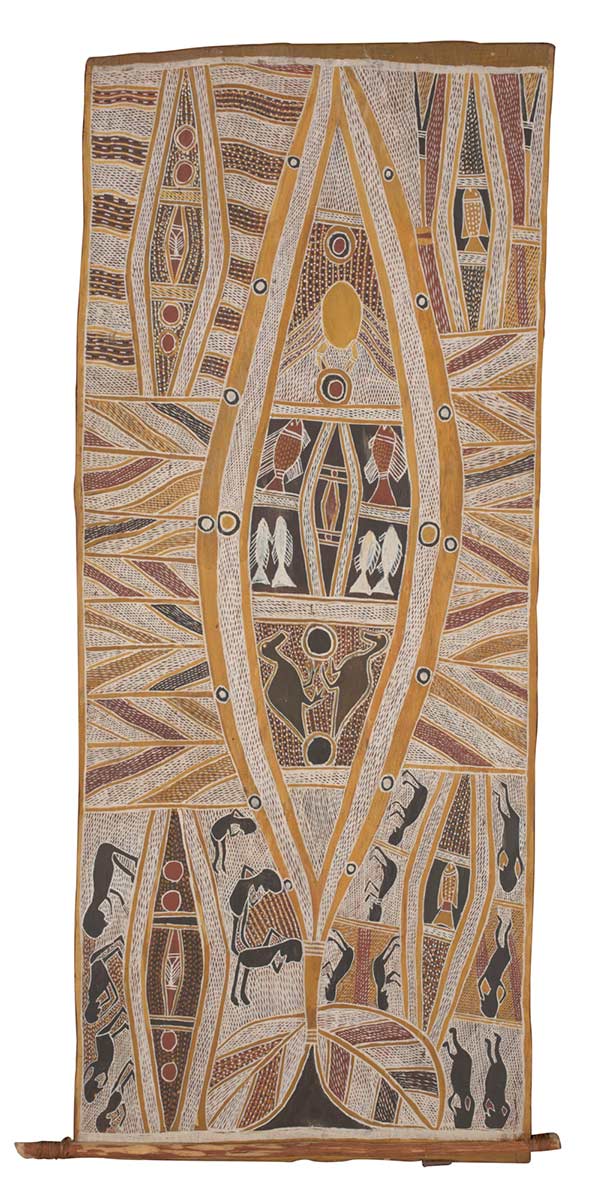

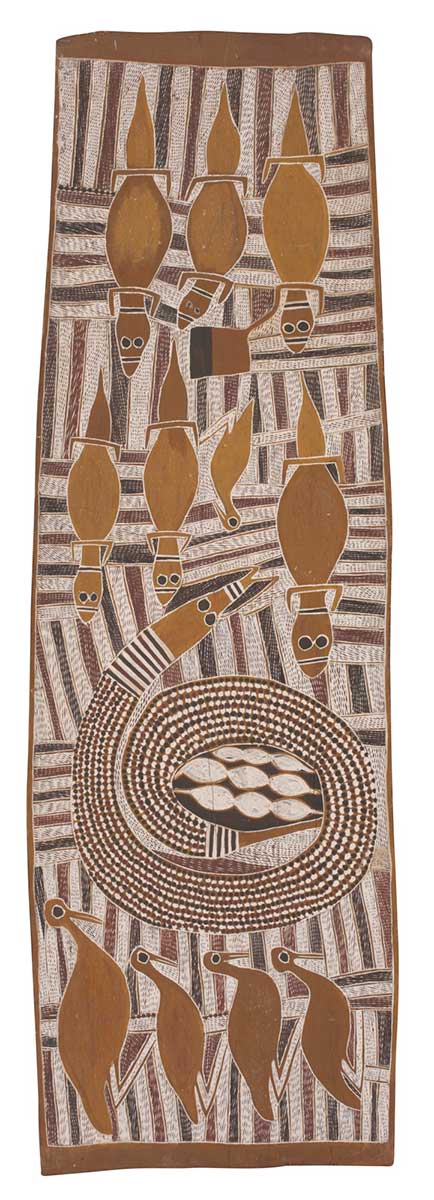

A recurring feature in Narritjin’s map-like paintings is the yiŋapuŋapu, an elliptical sand sculpture used in Yirritja mortuary ceremonies. Fish symbolising the body of the deceased are placed at the centre of the ground sculpture, while the anvil-shaped thunderhead cloud represents death. Sand crabs and maggots feed off the remains of fish in an act of cleansing. The yiŋapuŋapu at Djarrakpi connects to similar sand sculptures in Madarrpa and Dhalwaŋu clan lands on Blue Mud Bay.

The Gumana and Yunupiŋu dynasties of the moiety include the ceremonial leaders Birrikitji Gumana of the Dhalwaŋu clan, and Muŋgurrawuy Yunupiŋu of the Gumatj clan. Their atmospheric paintings evoke the freshwater rivers and fires of the Arnhem Land forests.

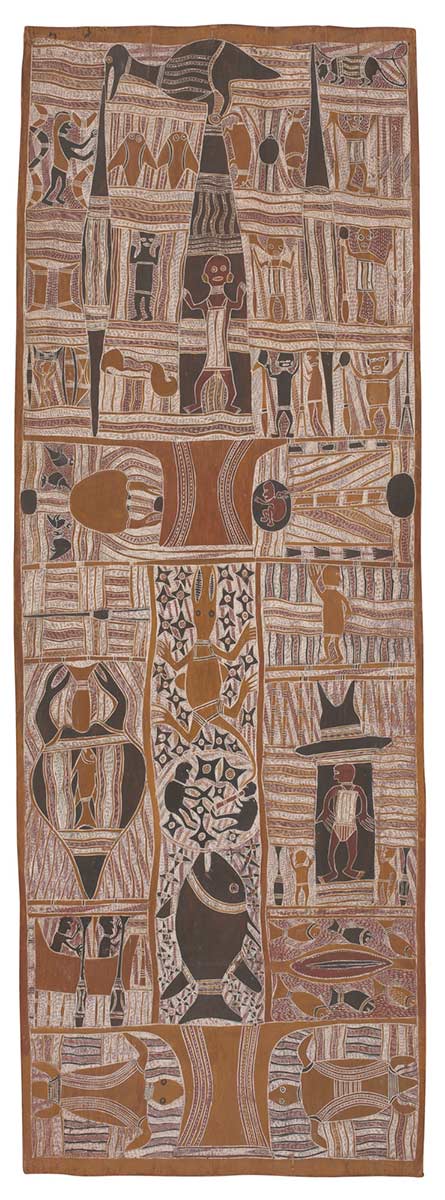

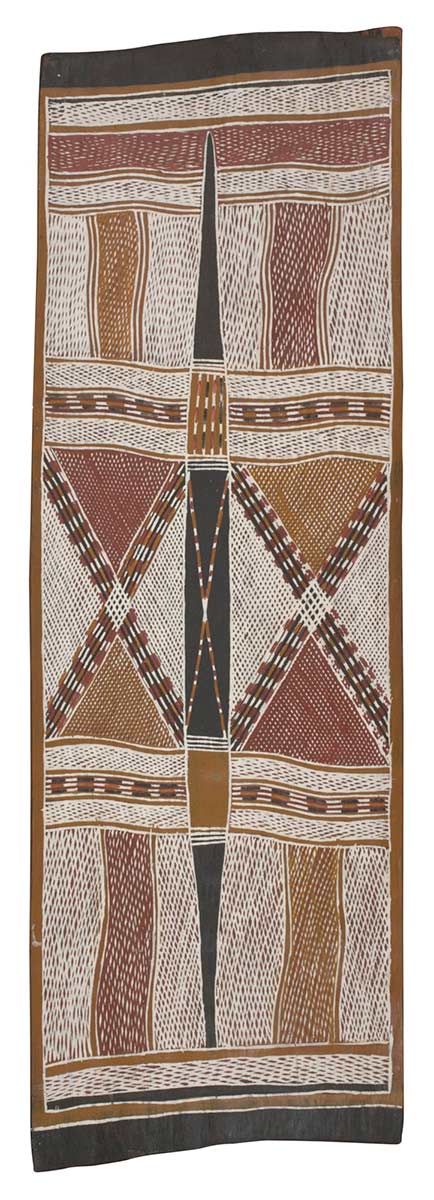

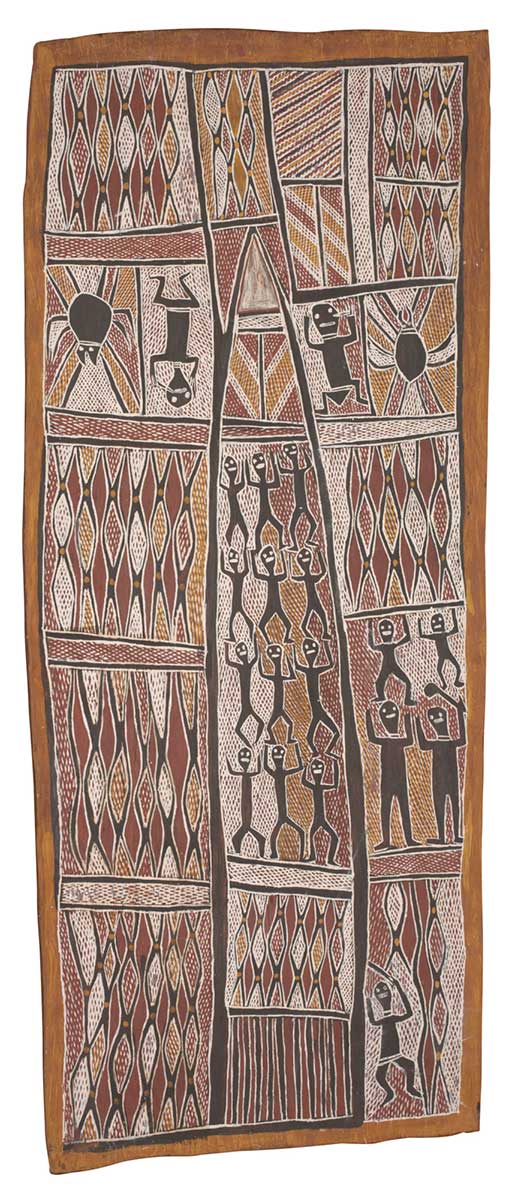

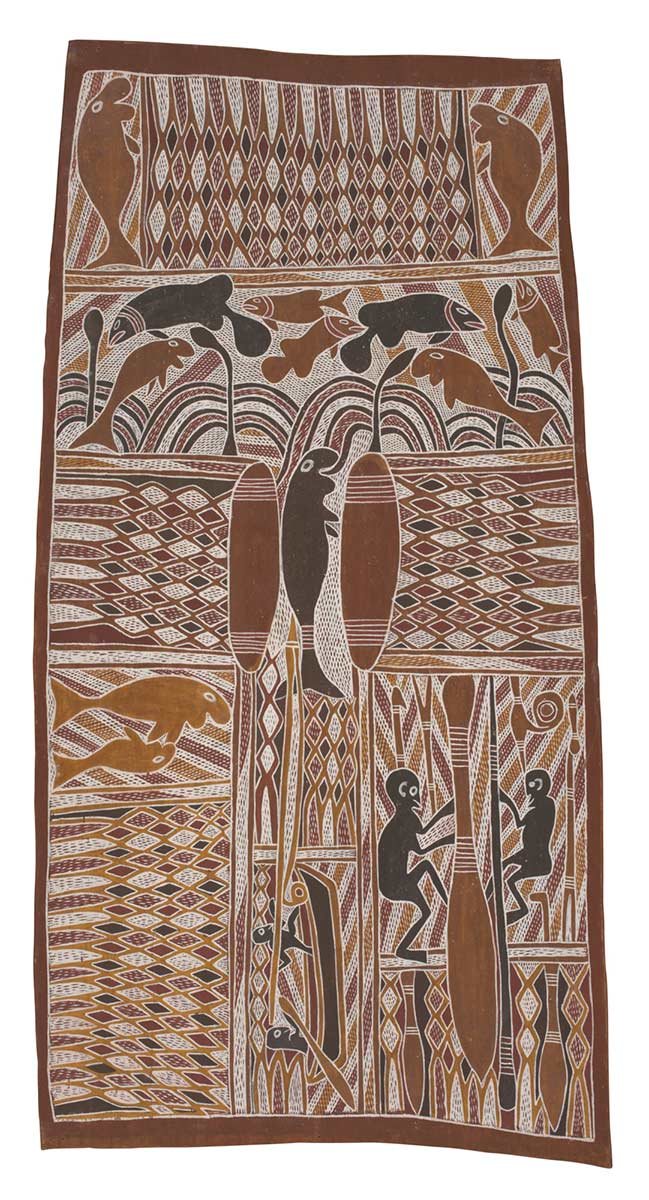

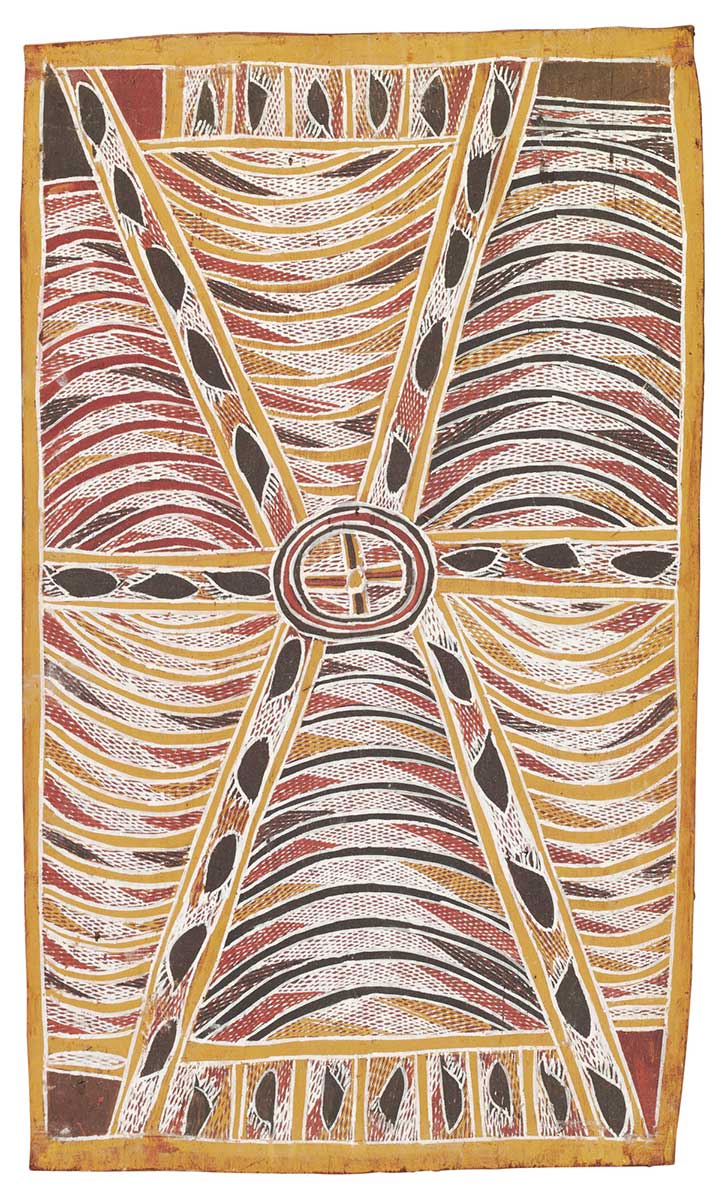

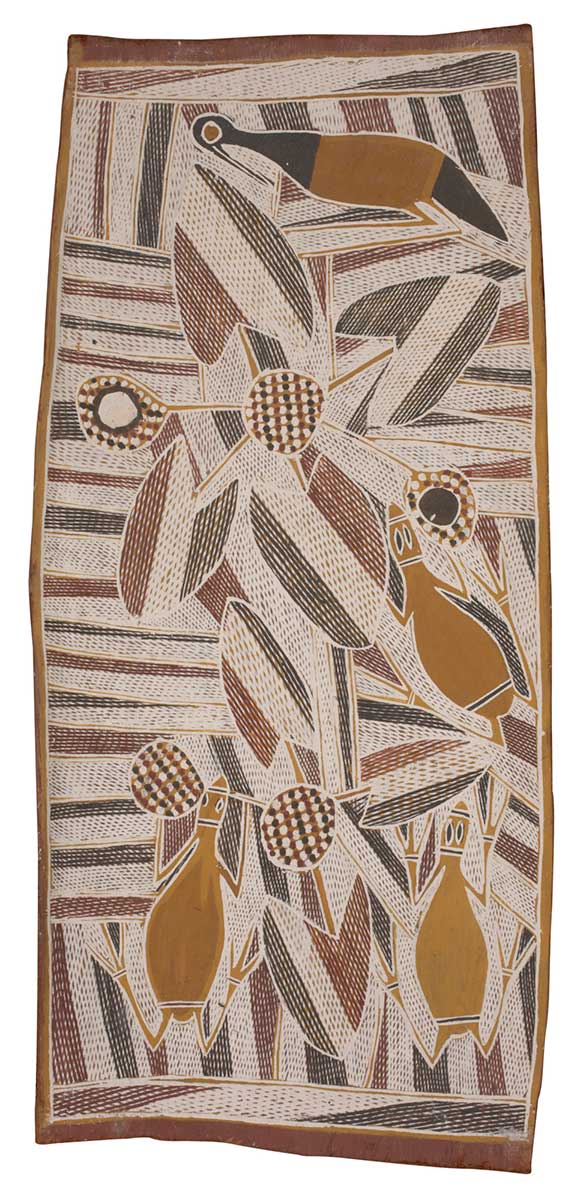

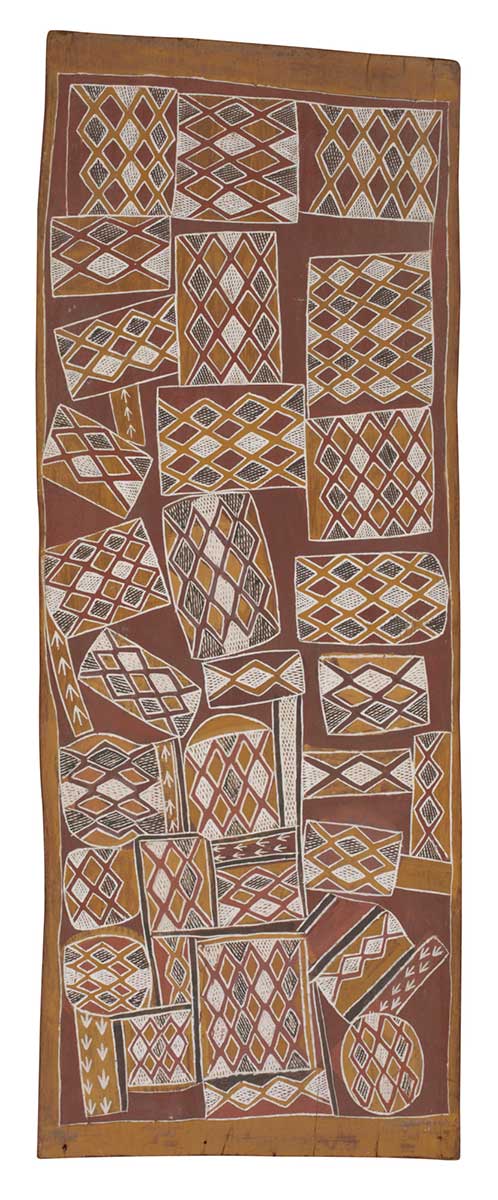

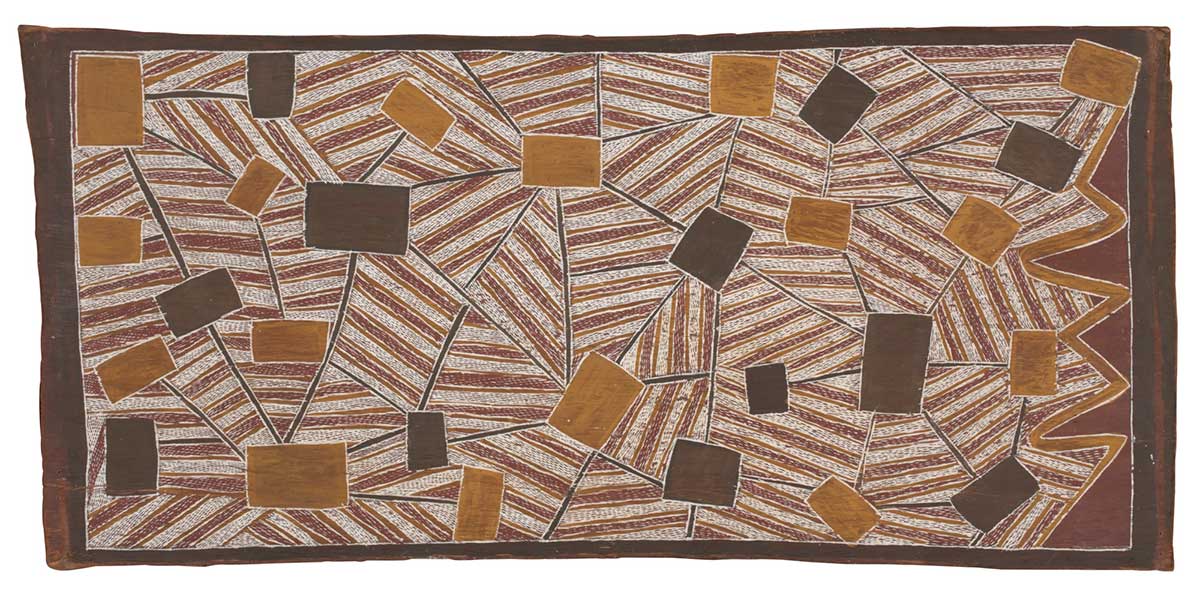

Muŋgurrawuy paints the ancestrally created fire that is used by Yolŋu as a land management technique known as firestick farming. The Great Bushfire Dreaming is a depiction of the use of fire to clear and regenerate the land, to prevent devastating wild fires and corral prey when hunting. The Gumatj miny’tji of linked diamond shapes seemingly shimmers with heat: the black, white and red crosshatching represents charred earth, smoke and ash, and burning cinders and fire respectively.

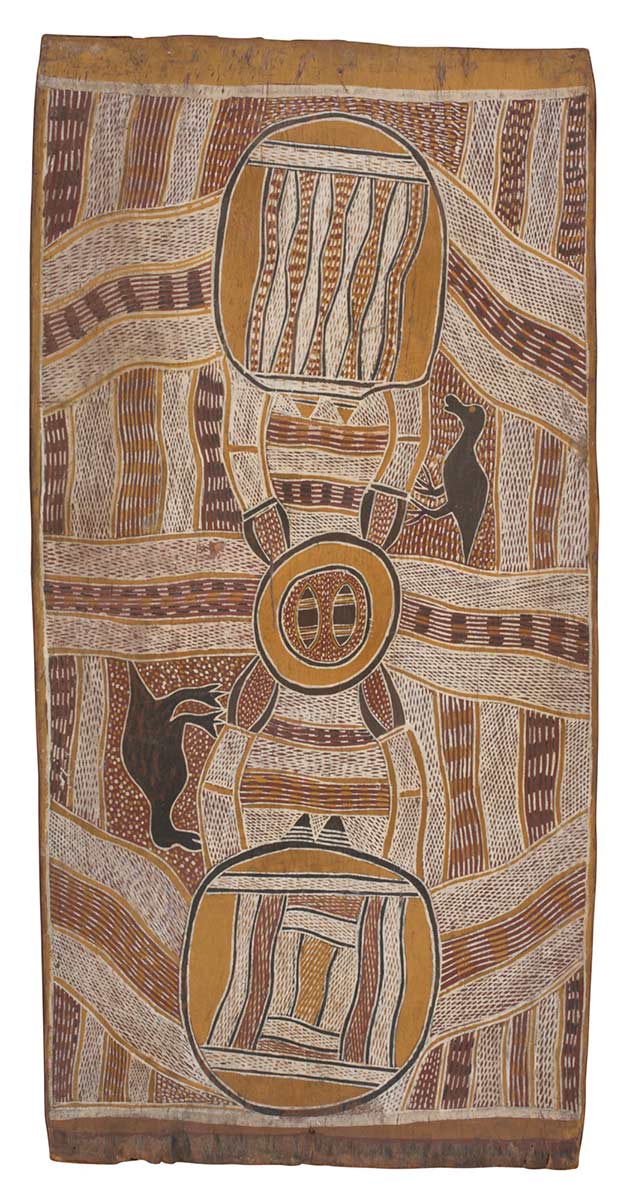

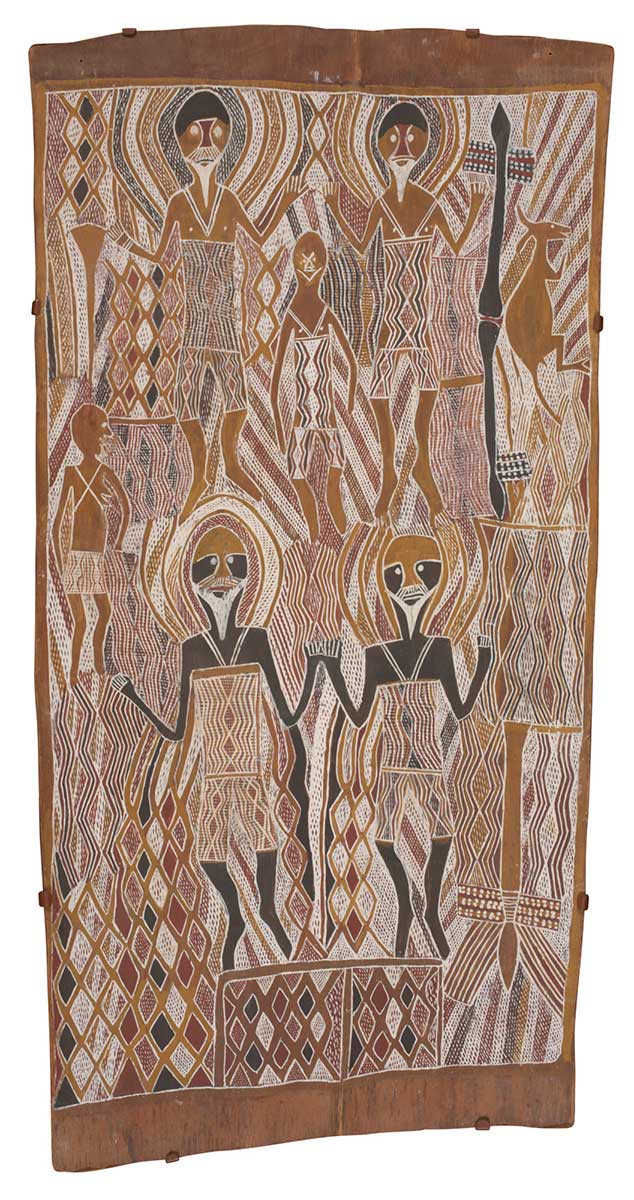

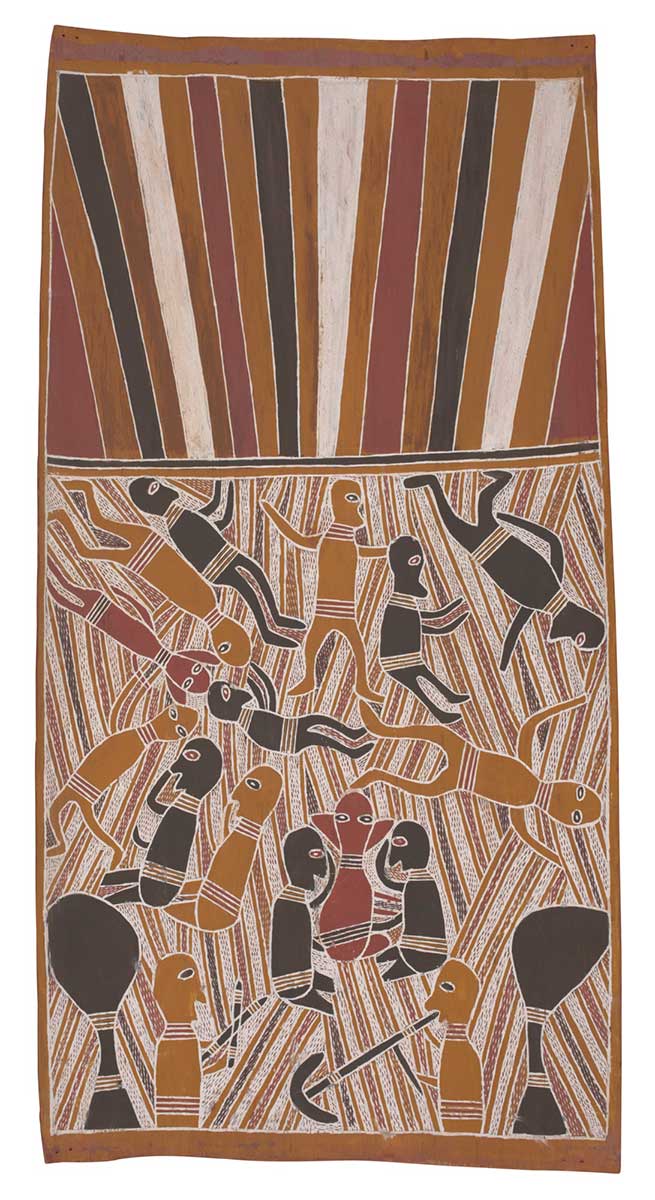

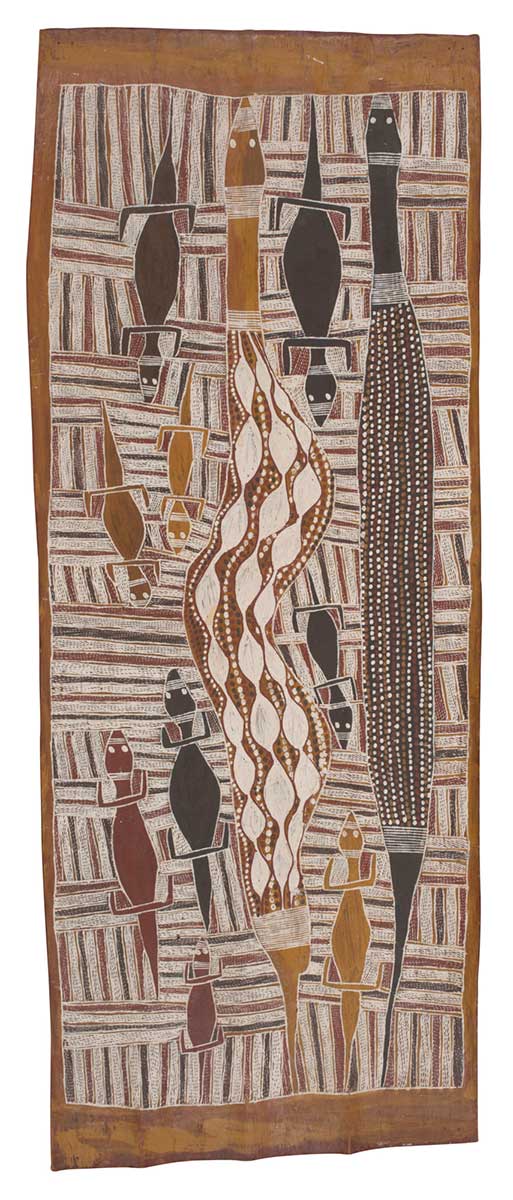

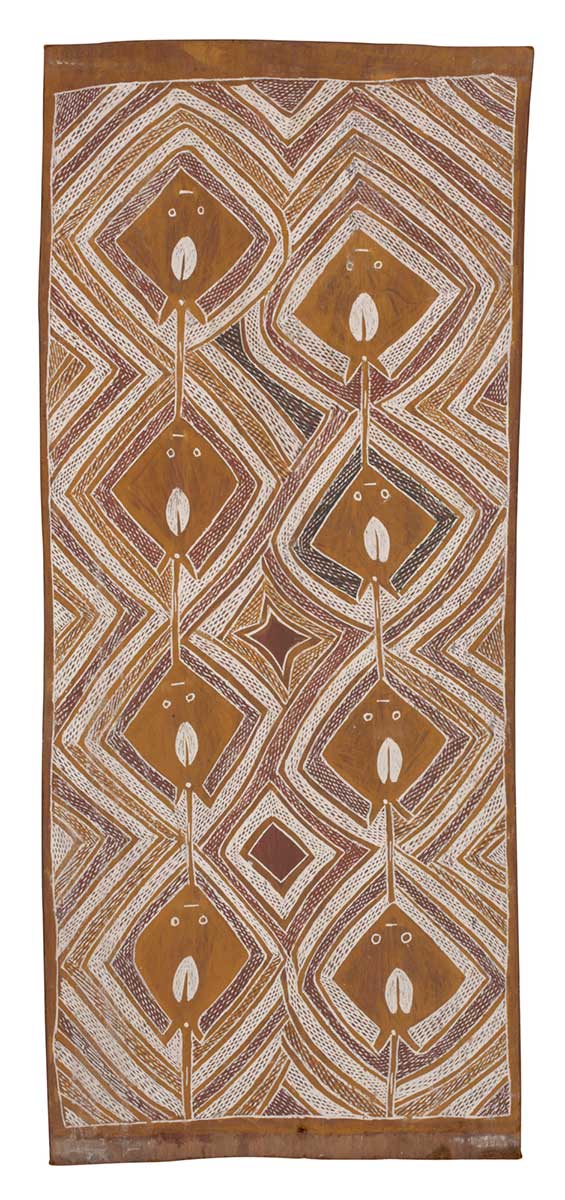

In Birrikitji’s The Four Great Yirritja Lawgivers, the figure in the lower left of the painting is the Yirritja ancestor Barama, who emerged at Gangan on the Koolatong River, his body covered in patterns made by salt water and with water weeds clinging to his skin. Barama instructed the other ancestors to distribute the law, miny’tji (sacred clan designs) and ritual objects among the Yirritja clans, as seen in Birrikitji’s son Gawirrin’s Barama Spreads the Sacred Law. The Dhalwaŋu clan pattern of linked rows of diamond shapes interrupted by an ellipse indicates the flowing fresh waters and billabongs of the Koolatong River.

Mutitjpuy Munuŋgurr had the authority to paint both Dhuwa and certain Yirritja themes. The Fire Dreaming at Yathikpa depicts the Yirritja Fire Dreaming site that is out to sea on Blue Mud Bay. The scene is reinterpreted abstractly by the patterns of linked diamonds: the red diamonds representing fire; the red crosshatching, sparks; the black diamonds, charcoal; and the white, ashes.

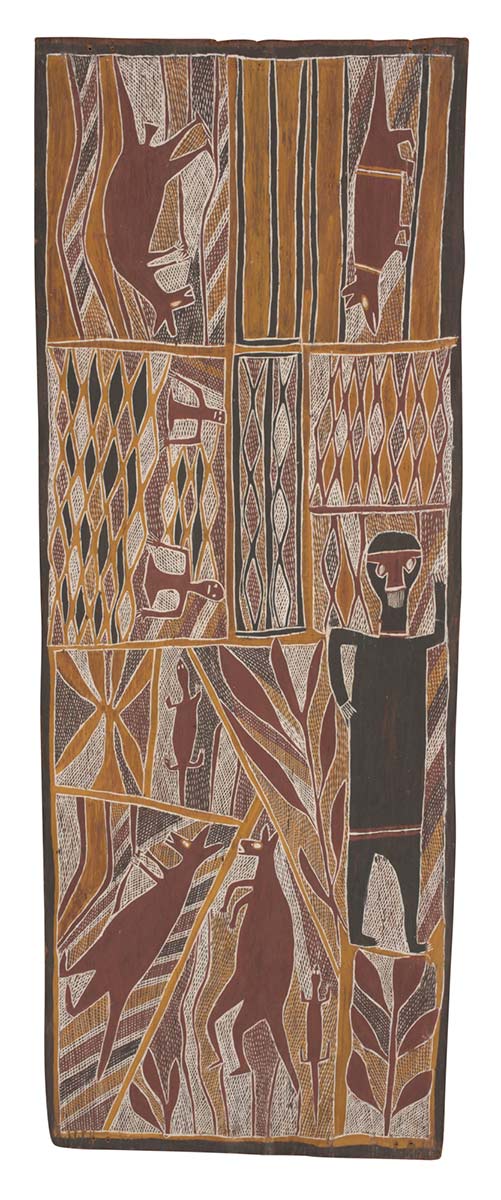

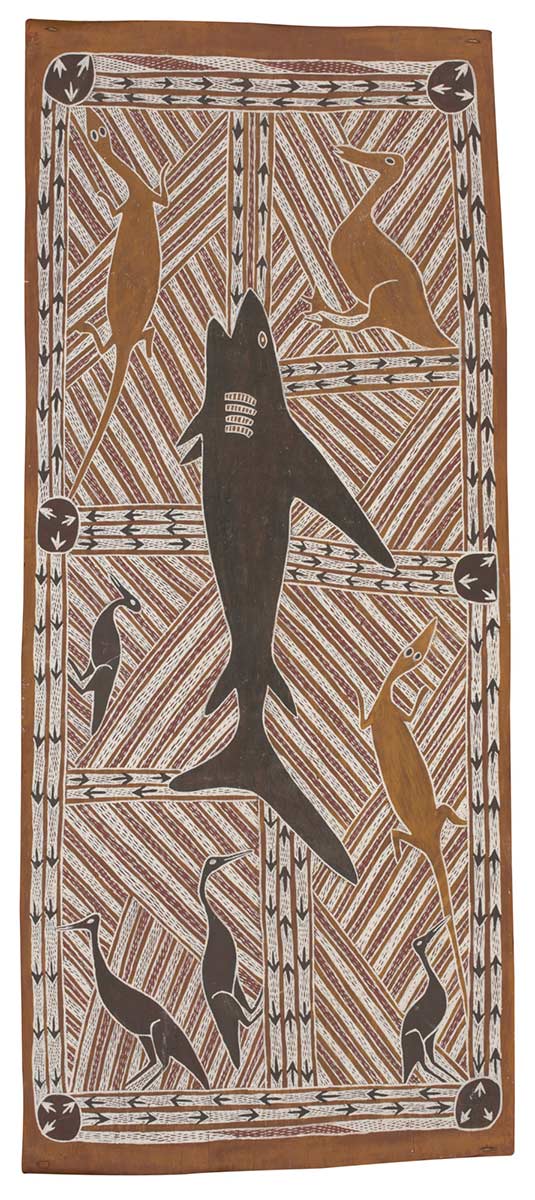

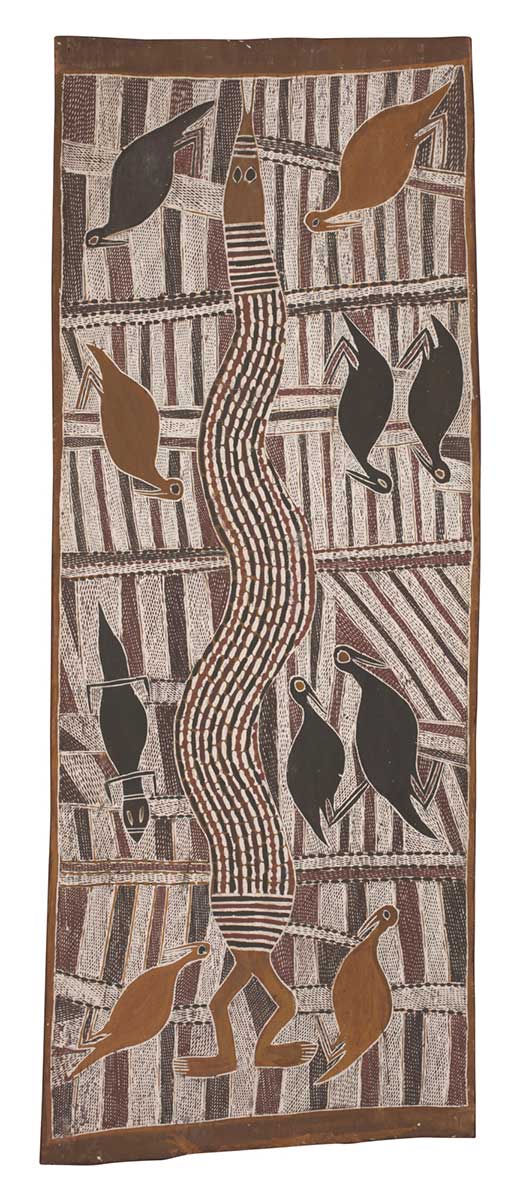

The grid structure in The Djan’kawu in Djapu Clan Territory with Mäna the Shark shows Mäna far inland in Djapu country, created by the Dhuwa ancestors, the Djan’kawu.

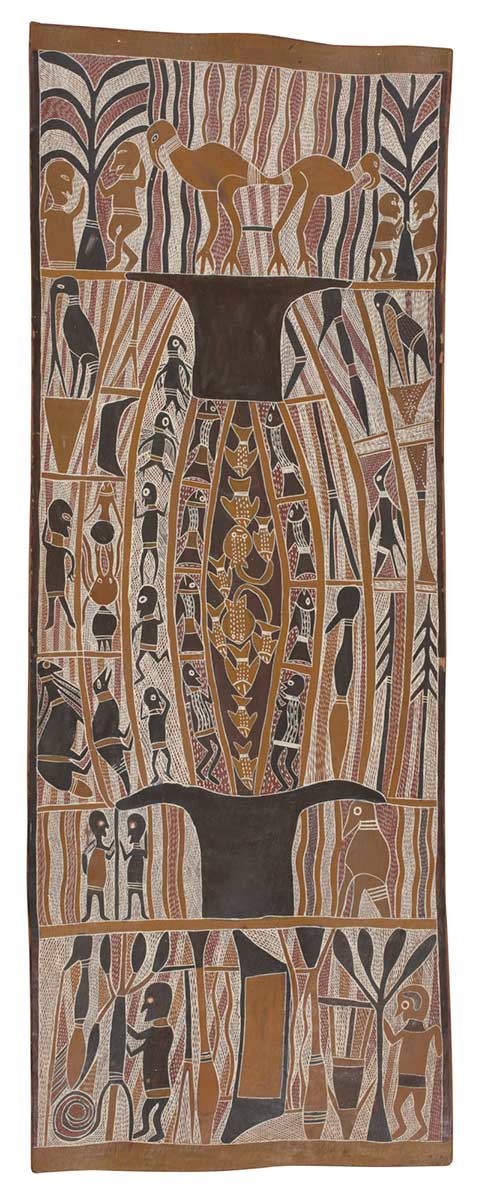

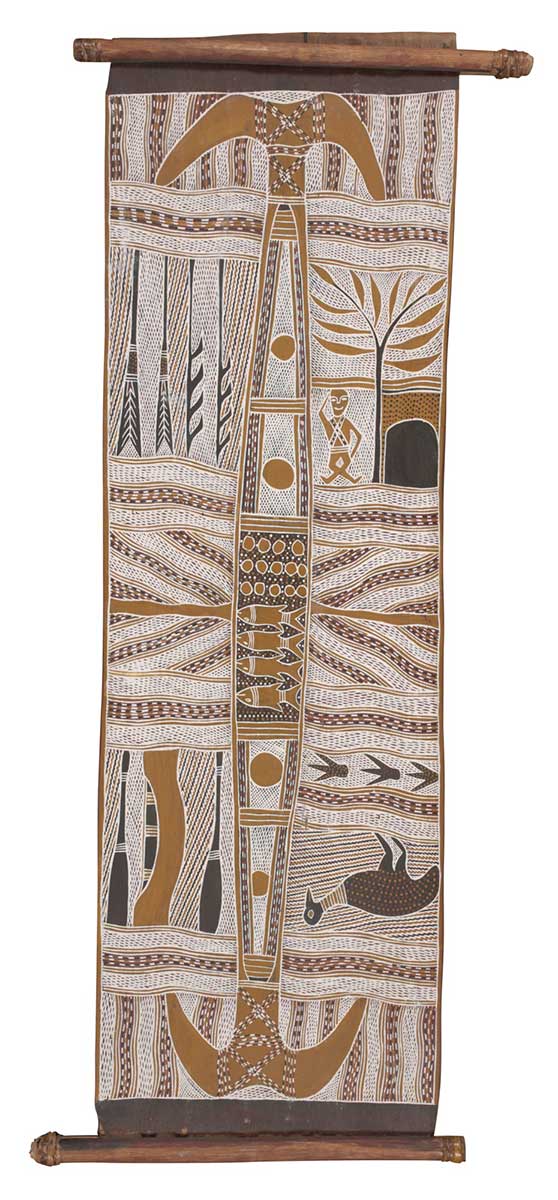

Mawalan Marika was the leader of the Rirratjiŋu clan and the head of an artistic dynasty that included his brother Mathaman and his son Wandjuk. The main ancestors of the Rirratjiŋu are the Djan’kawu, referred to in Wandjuk’s The Sacred Waterhole at Bilapinya, which features the Union-Jack-like design showing the paths the ancestors took as they created this freshwater spring.

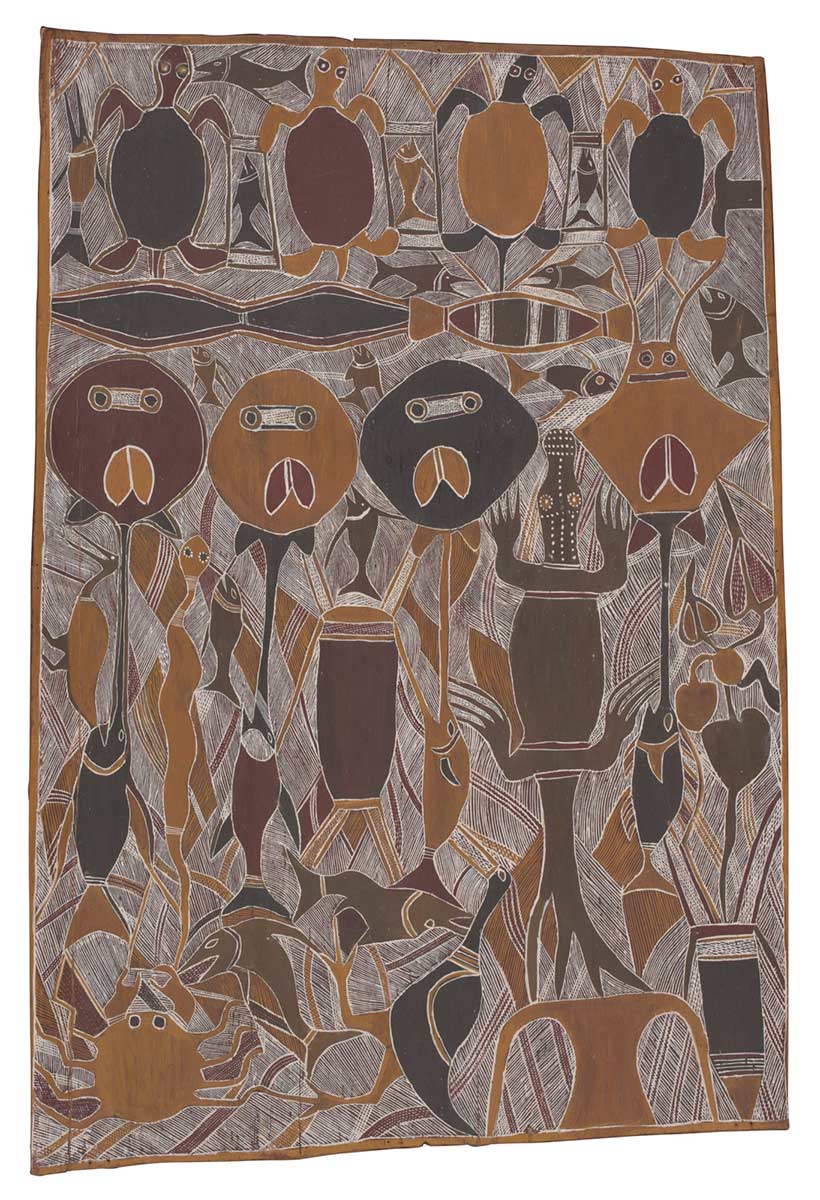

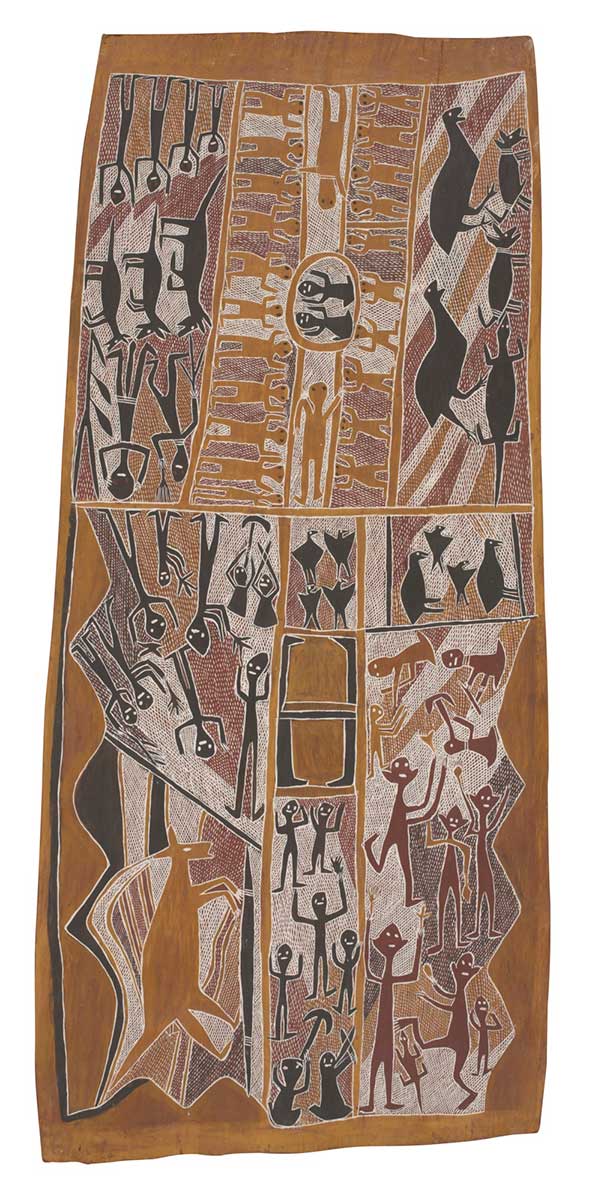

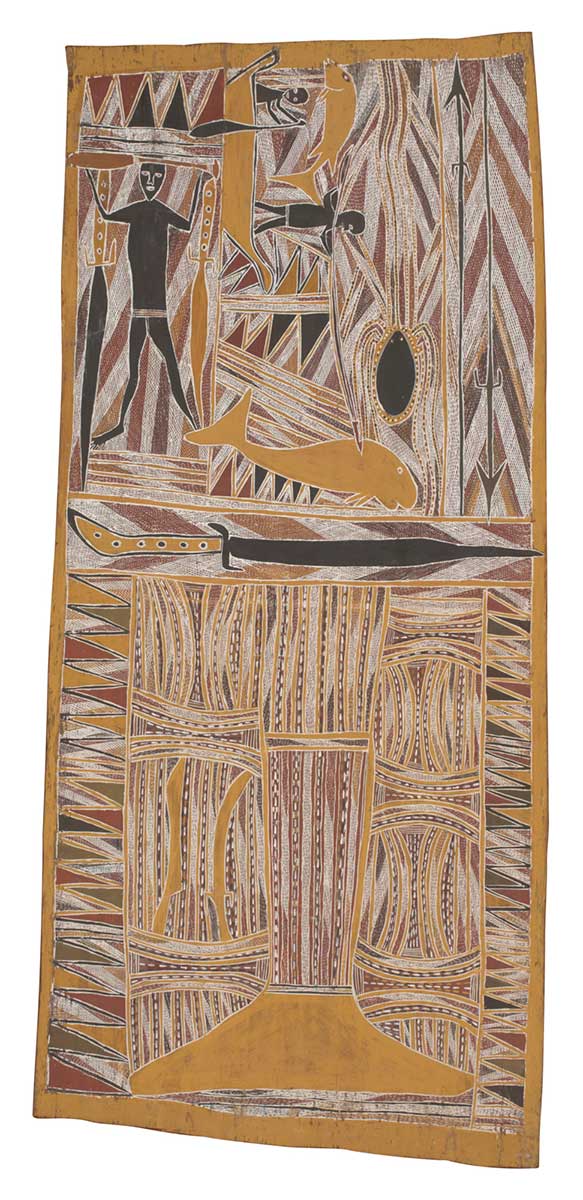

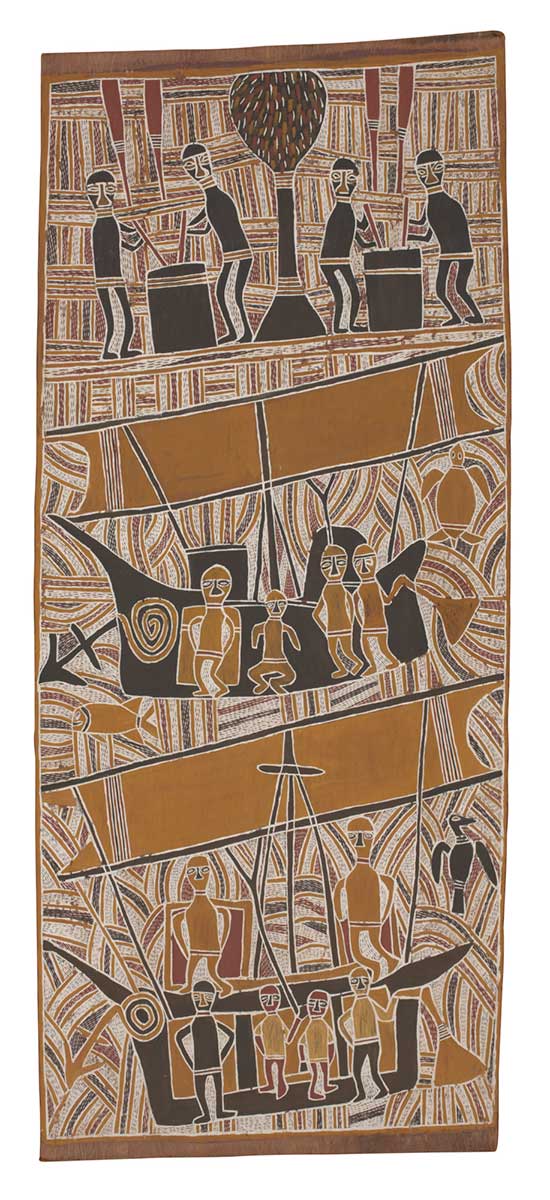

Mathaman paints another set of Dhuwa ancestors, the Wäwilak Sisters. In the upper panel of Rirratjiŋu Mortuary Ceremony the rays of the sun capture dust rising from the ground as people dance in the ceremony depicted below. Here, the spirit of the deceased is taught how to make paddles and is given a canoe to row to Dhambaliya (Bremer Island) on its way to the ancestral realm.

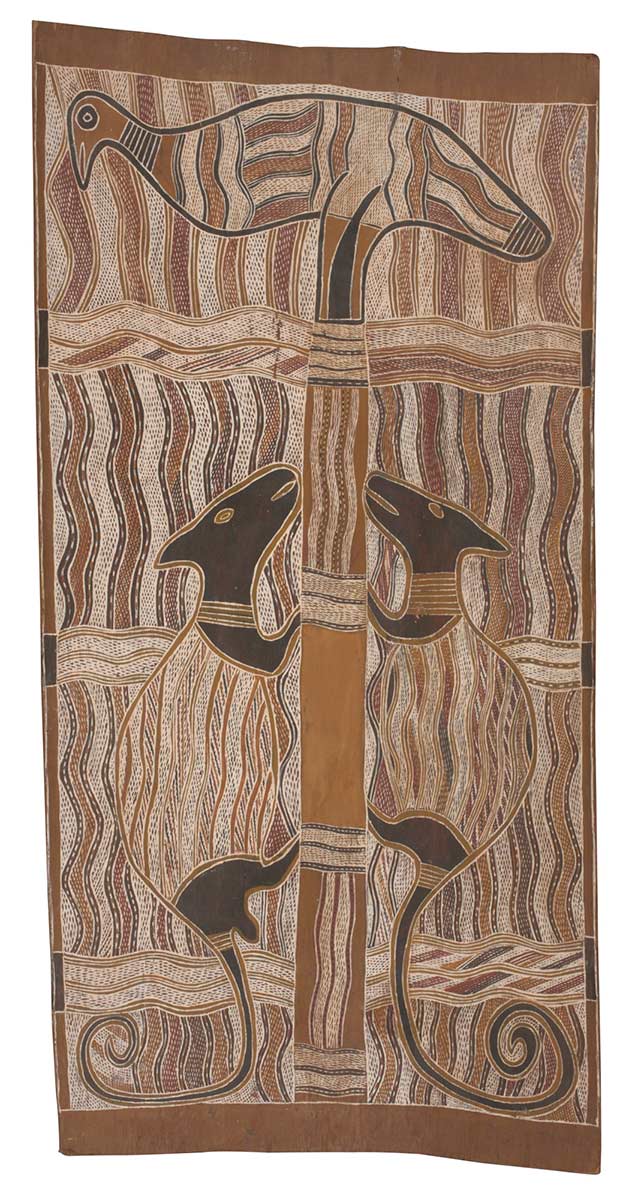

In Mawalan’s painting, the Milky Way is regarded as a river in the sky teeming with constellations in the form of totemic species. Wandjuk’s The Tail of the Whale Daymirri features the steel-bladed knives used to butcher a whale whose tail became a symbol of the thunderhead clouds of the early wet season. The anvil-shaped yellow cloud pouring rain appears upside-down in this orientation because the artist turned the bark around as he painted the picture.

Mithinarri Gurruwiwi depicts the male and female Rainbow Serpents of his clan, the Gälpu. They feature in the Wäwilak Sisters story, in which Wititj the Rainbow Serpent swallows the sisters at Mirarrmina, then stands erect in the sky and boasts of his deed to ancestral Rainbow Serpents belonging to neighbouring clans, including the Gälpu. These serpents make Wititj aware he has broken the law by devouring beings who belong to the same moiety as him – a metaphor for a marriage between kin that is forbidden by law.

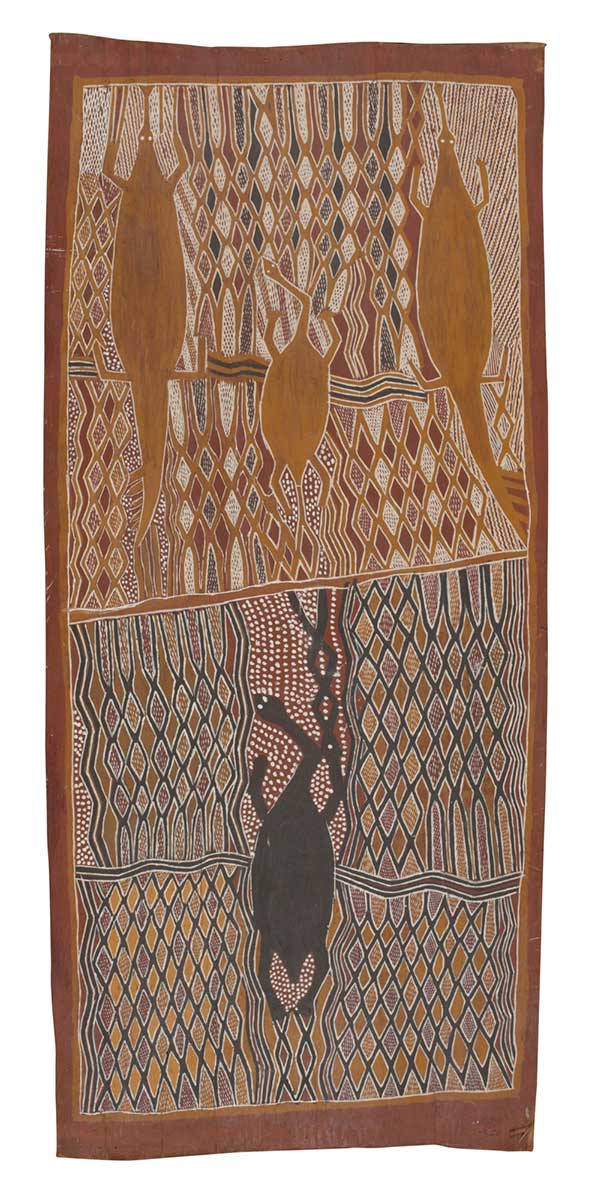

Wititj becomes ill and expels the women, as Mithinarri suggests in Wititj the Gälpu Python by depicting the legs of one of the sisters emerging from the snake’s anus. Just as Wititj at Mirarrmina created the first monsoon, the Gälpu snakes also make rain clouds, and their flickering tongues become lightning.

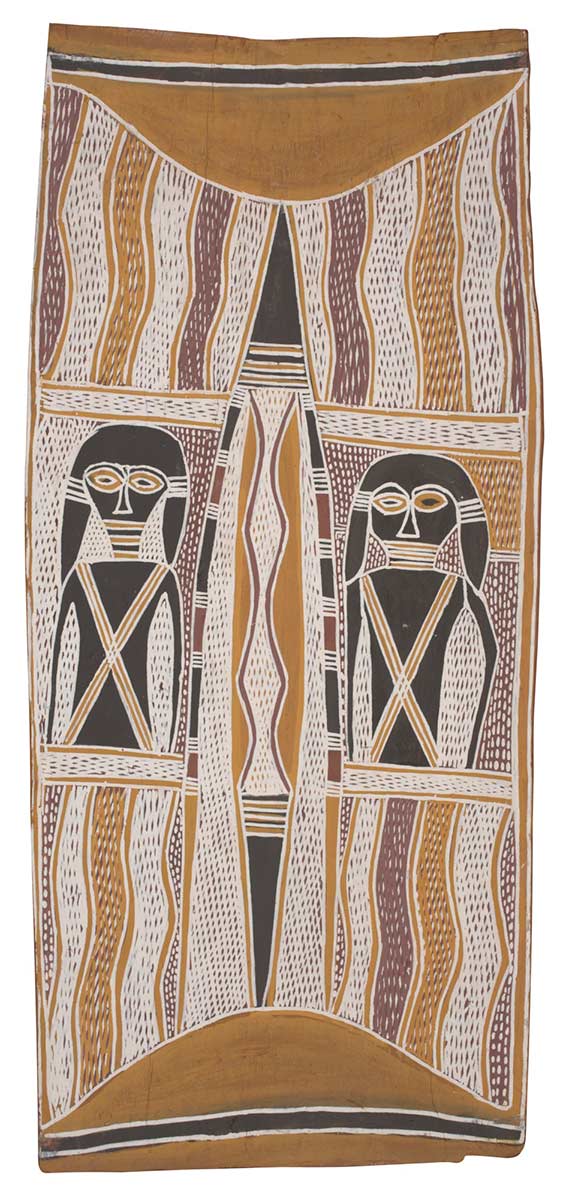

In Male and Female Wititj the extraordinary fertility of the snakes is emphasised by the depiction of eggs within the female’s body. The background Gälpu clan pattern represents paperbark trees.

In Wititj the Gälpu Snake, a goanna carries a rectangular quartz axe-head to make the connection between Gälpu country and Ŋilipitji, a site near Mirarrmina where quartz is quarried to make blades and knives.s

Abstraction in Western art history is a term applied to paintings of predominantly geometric forms or to images without obvious external referents. Abstract art emphasises the formal and expressive properties of line, shape and colour to elicit an aesthetic reaction beyond words. In Aboriginal bark painting there is an interplay between figurative and non-figurative imagery, between the representational and the abstracted, so that both may exist simultaneously within a painting.

The landscape may be perceived as sets of abstracted patterns and designs. In several of Birrikitji Gumana’s paintings, regular rows of stingrays are surrounded by a Dhalwaŋu clan design to create a mesmerising pattern of eddies and pools of light reflected in the water.

By way of contrast, his Ŋärra Ceremony is a syncopated juxtaposition of sections of Dhalwaŋu body designs referring to fire. West Arnhem Land painter Bob Balirrbalirr Dirdi’s enigmatic tracery of yam roots and tubers may in fact double as an image of a serpent.

Mawalan Marika created a series of innovative ‘abstract’ paintings after his first visit to a big city – Sydney – in 1961. One of these captures his impression of buildings and roads seen from the air.

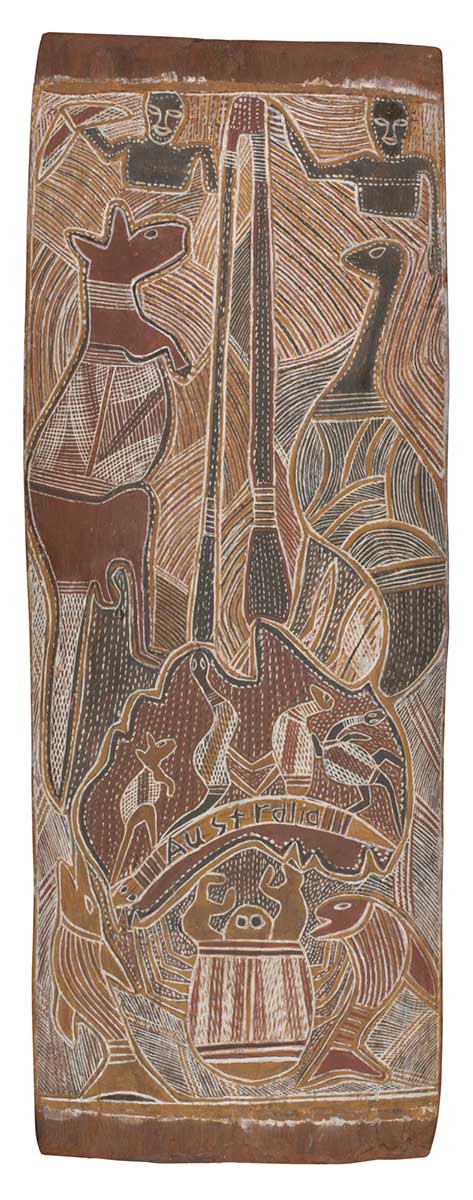

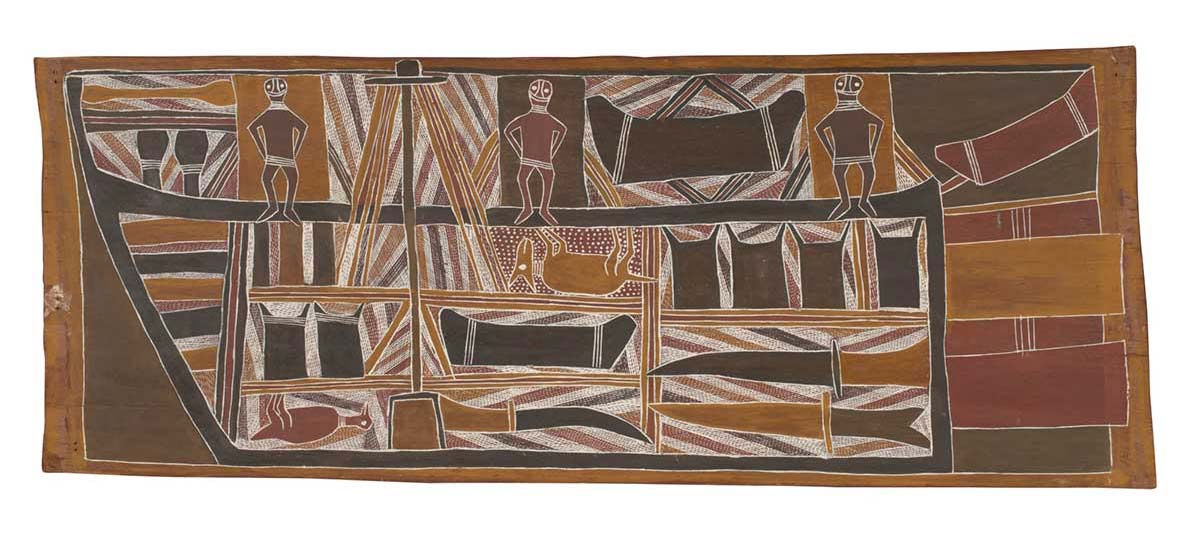

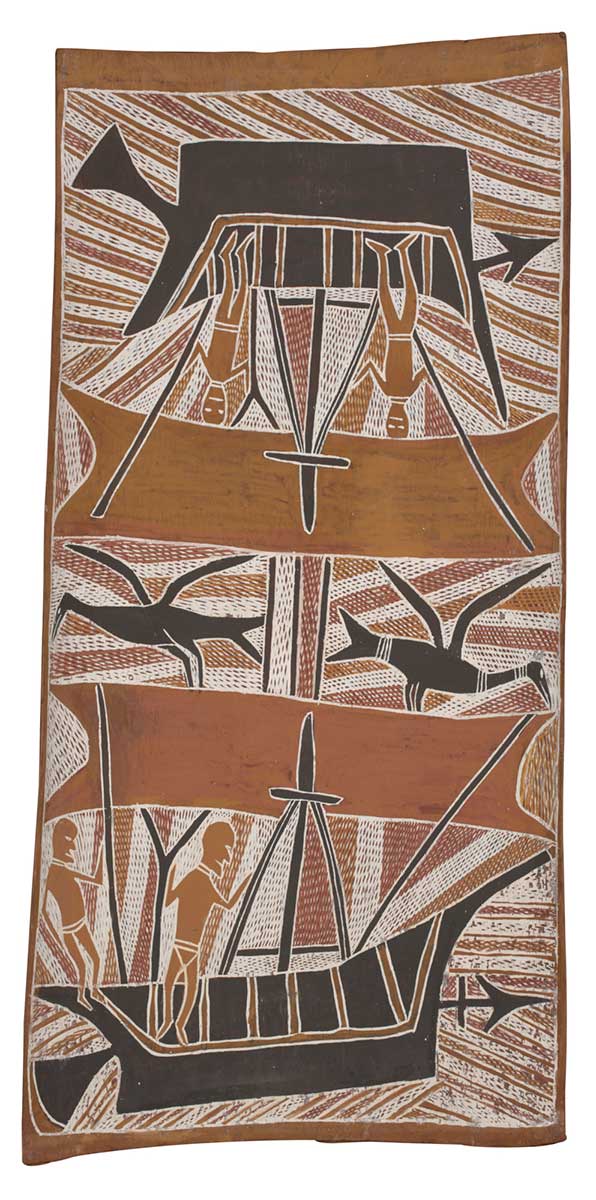

Trepangers from Makassar, in Sulawesi, Indonesia, visited the shores of Arnhem Land every wet season for more than 200 years until 1907, after the introduction of the government’s White Australia Policy. They came in fleets of prau to collect trepang (sea cucumbers), a delicacy in South-East Asia. The Makasar people established friendly relationships with Yolŋu, a number of whom sailed back with the visitors to Makassar and settled there.

The Makasar did not settle in Arnhem Land but they did have an influence on Yolŋu society and ritual. They introduced calico, tobacco and smoking pipes, and words that are still in use today, such as rrupiya (money). Most importantly they introduced an item of technology that transformed Yolŋu life – metal. Metal blades, knives and axes made everyday practices easier for Yolŋu, from cutting food to making large dugout canoes and complex wooden sculptures.

Although not part of the Dreaming, the Makasar did enter Yolŋu cosmology. The prau sail disappearing over the horizon at the end of the wet season, for example, is symbolic of the soul leaving this world for the ancestral realm. Birrikitji Gumana’s painting Makasar Prau recalls his meeting with the trepangers when he was young. Mathaman Marika uses variations of the Rirratjiŋu clan design to indicate dry land and the sea.