The artists of central Arnhem Land belong to the Yolŋu-speaking groups whose lands extend to the east coast of Arnhem Land.

Most people in this area moved from their traditional lands to the Christian mission on the island of Milingimbi after it was established in 1923, and to the postwar mainland settlements of Maningrida and Ramingining, before returning to their customary lands in the 1970s and 1980s.

In central Arnhem Land, the style of painting draws on elements of the figurative imagery of the west, and the detailed patterning and geometric compositions of the east.

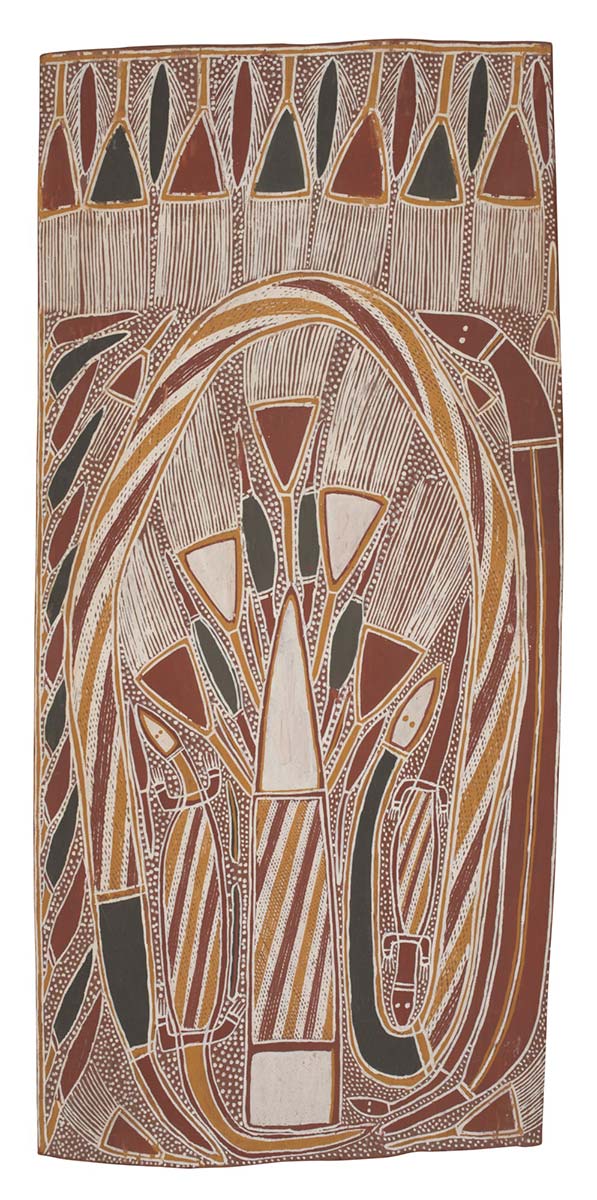

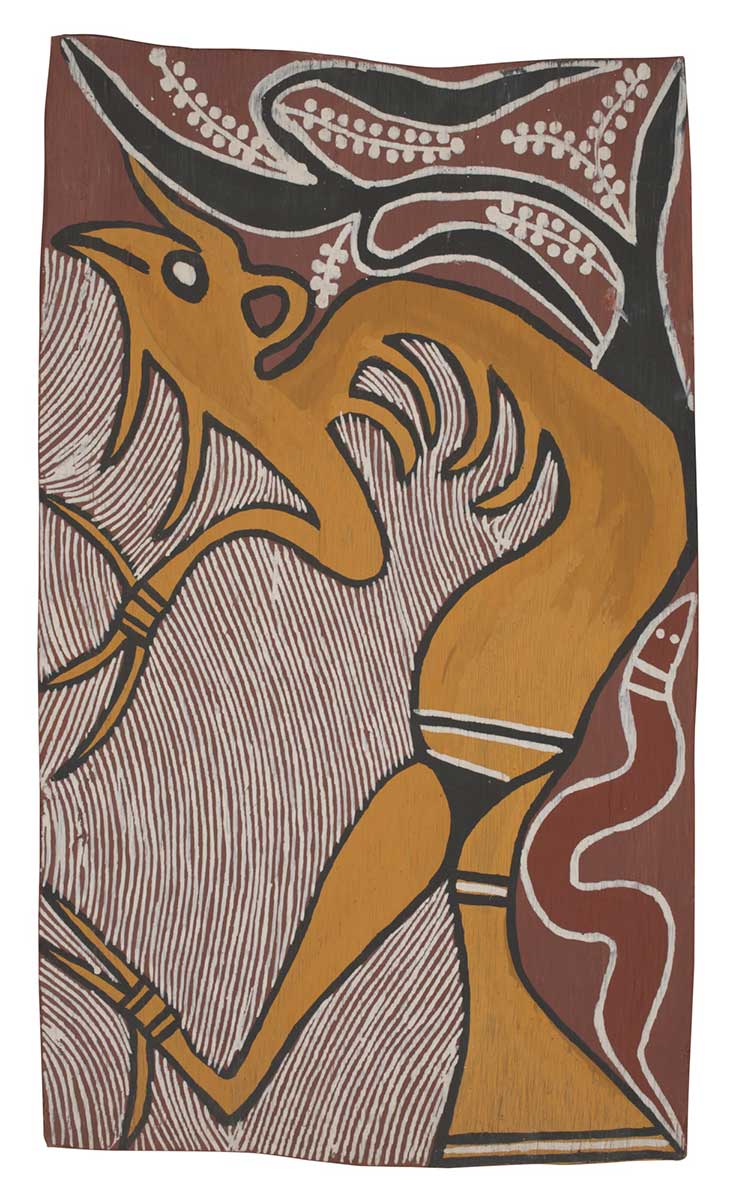

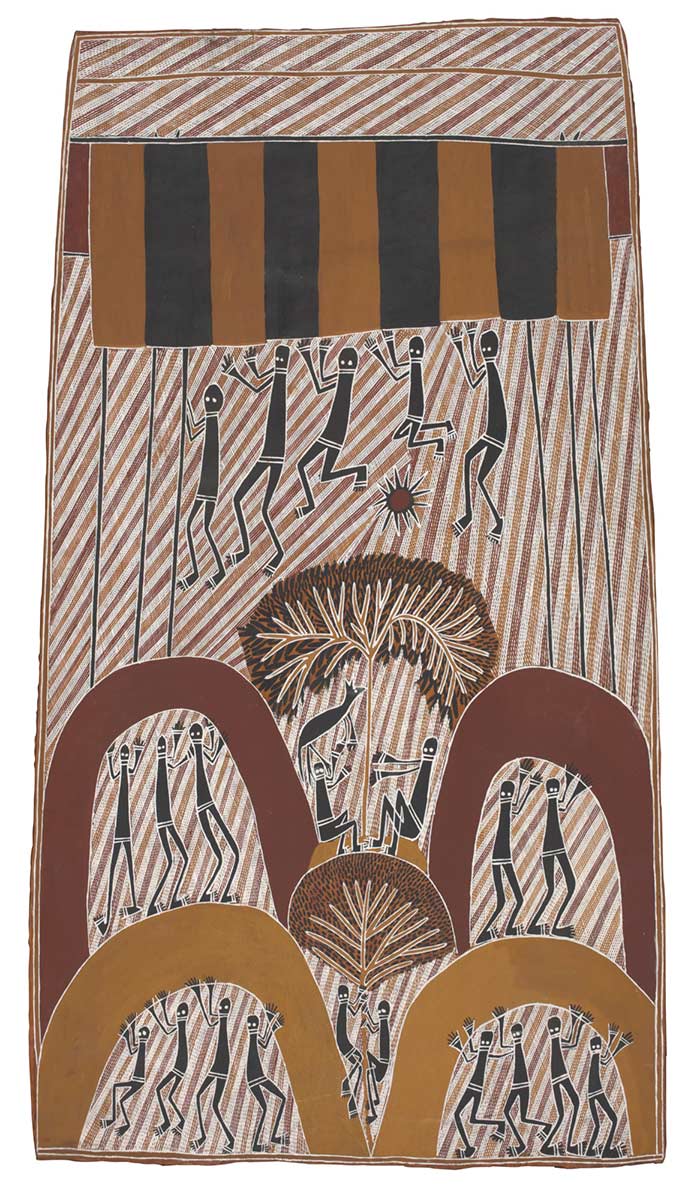

Dawidi became the leader of ceremonies associated with the ancestral Wägilak Sisters on the death of his father, Yilkari Kitani (1891–1956). As Dawidi was still an inexperienced painter he was tutored by a senior artist, Dhawadanygulili (1900–1976). When Dawidi died, his brother Paddy Dhäthaŋu inherited his role.

The Wägilak story concerns the rules of marriage, the creation of the first monsoon and the concept of transformation. In the narrative, Wititj the Rainbow Serpent swallows the Wägilak Sisters but regurgitates them when he realises they belong to his moiety, the Dhuwa. The sequence of swallowing and regurgitation is a metaphor for transformation, as in initiation where boys enter the ceremony and emerge as men.

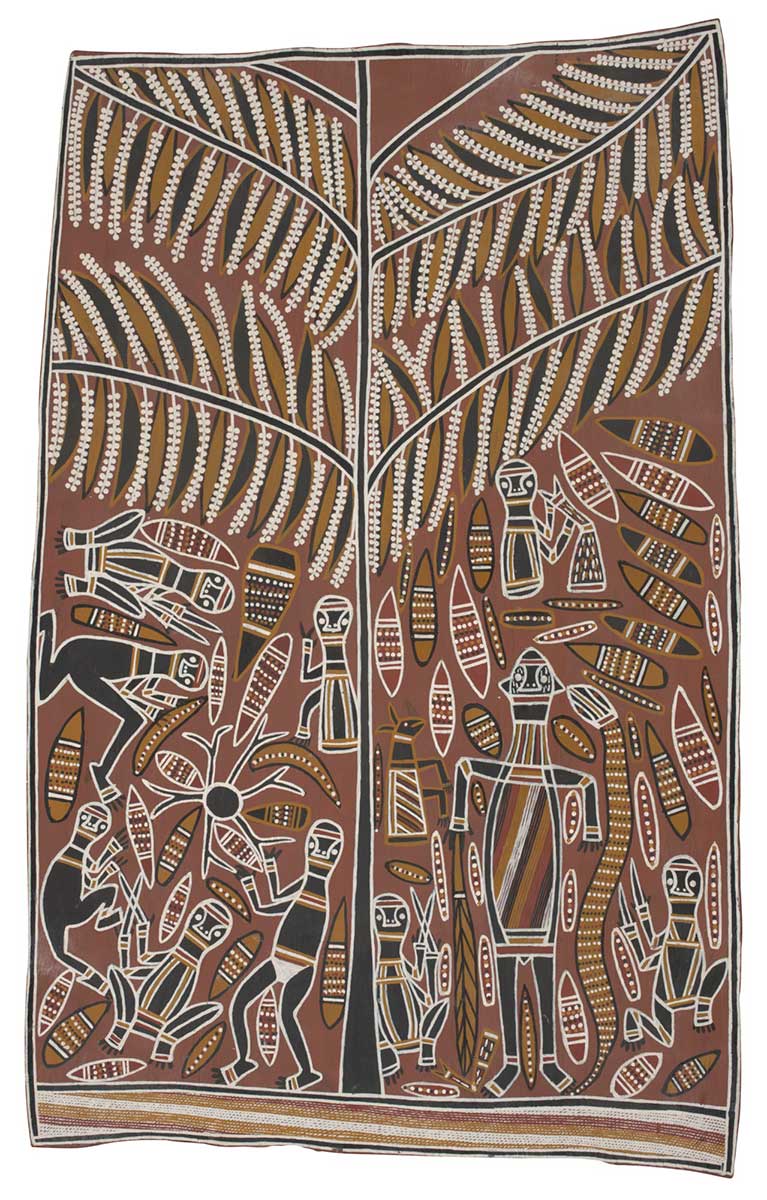

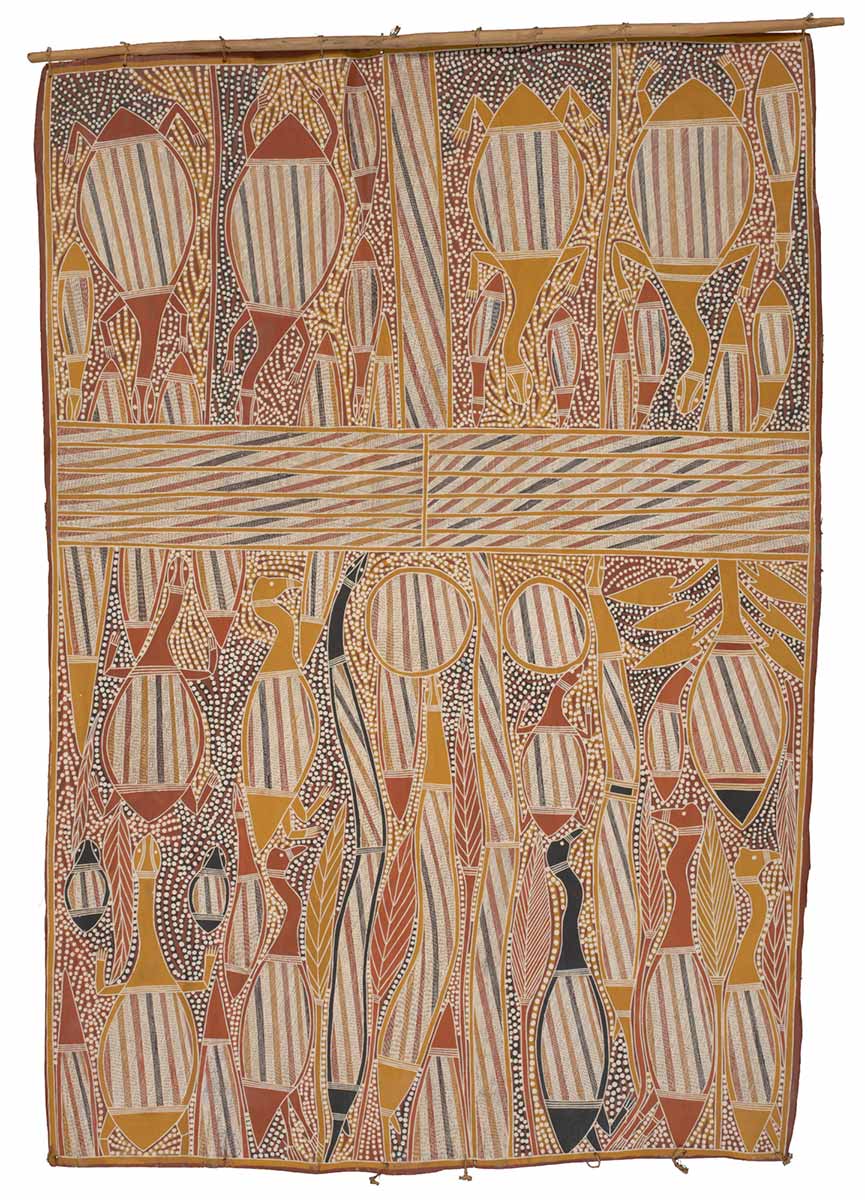

The Djan’kawu – two sisters and their brother – are the major ancestors of the Dhuwa moiety. They created the first human beings and organised them into clans, allocated land and provided fresh water by plunging their digging sticks into the ground. They came to Arnhem Land from the east, across the sea.

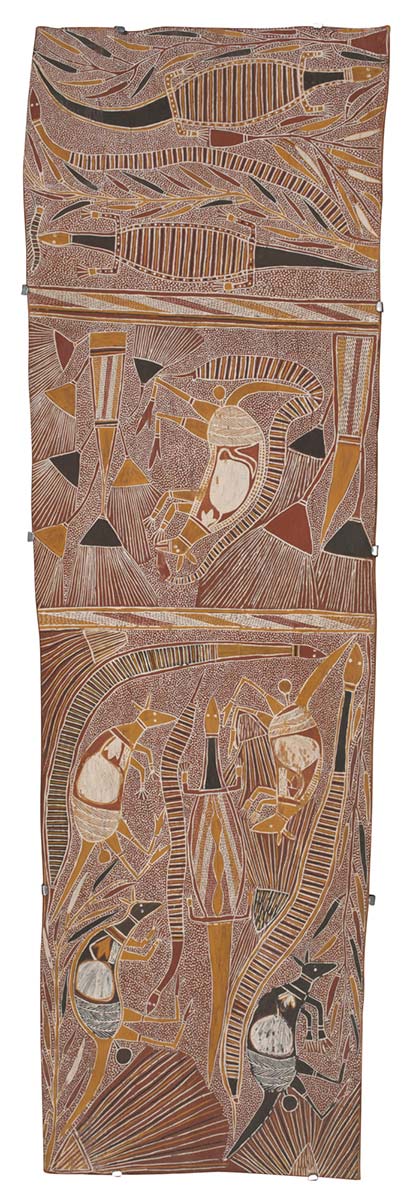

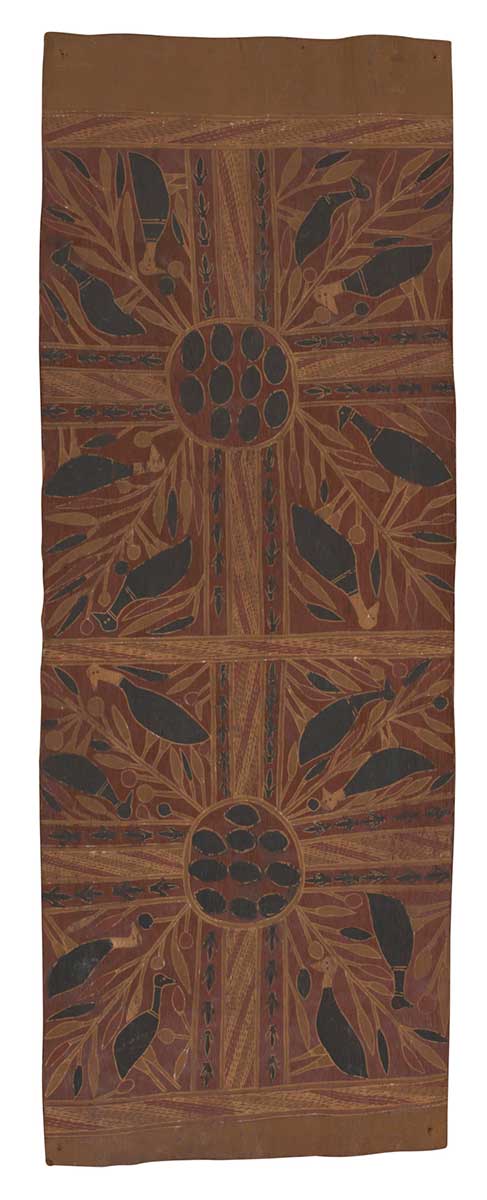

Djunmal’s The Sea Voyage of the Djan’kawu Sisters depicts sea creatures that the ancestors saw as they paddled ashore. Tom Djawa’s Emu Dance shows two inland sites they created. The Union-Jack-like design represents the Djan’kawu, and the circles are freshwater wells. In Valerie Munininy 2’s painting a variation of the Djan’kawu design is shown among beds of oysters, at a site called Gärriyak.

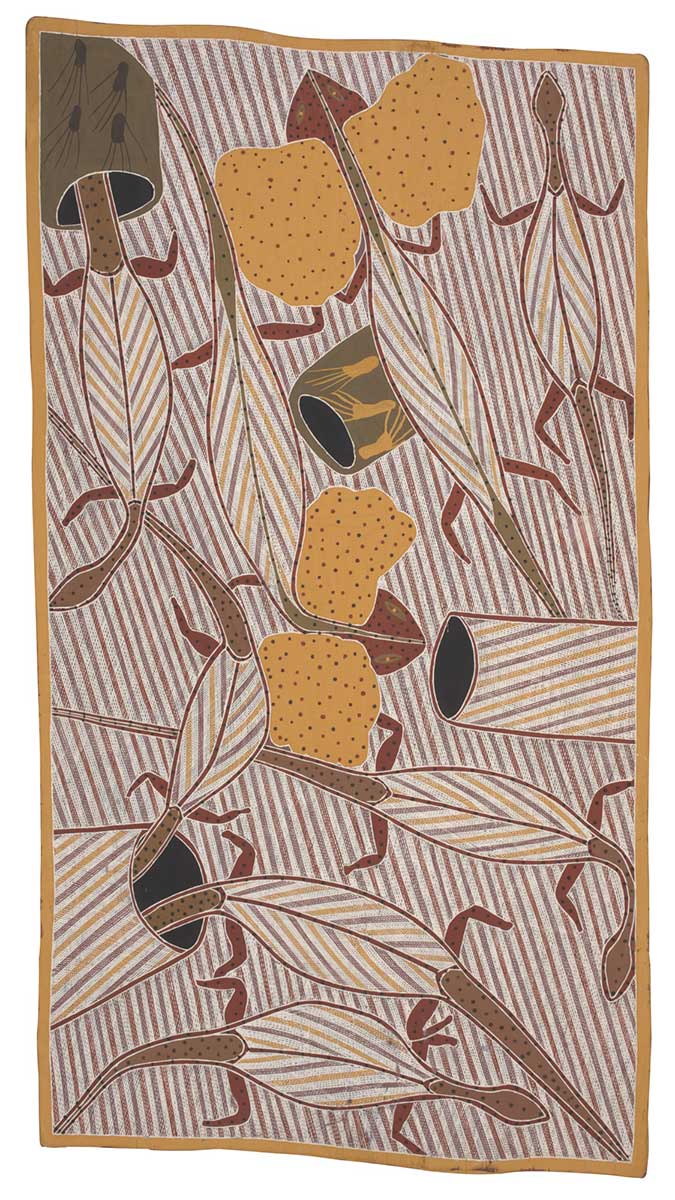

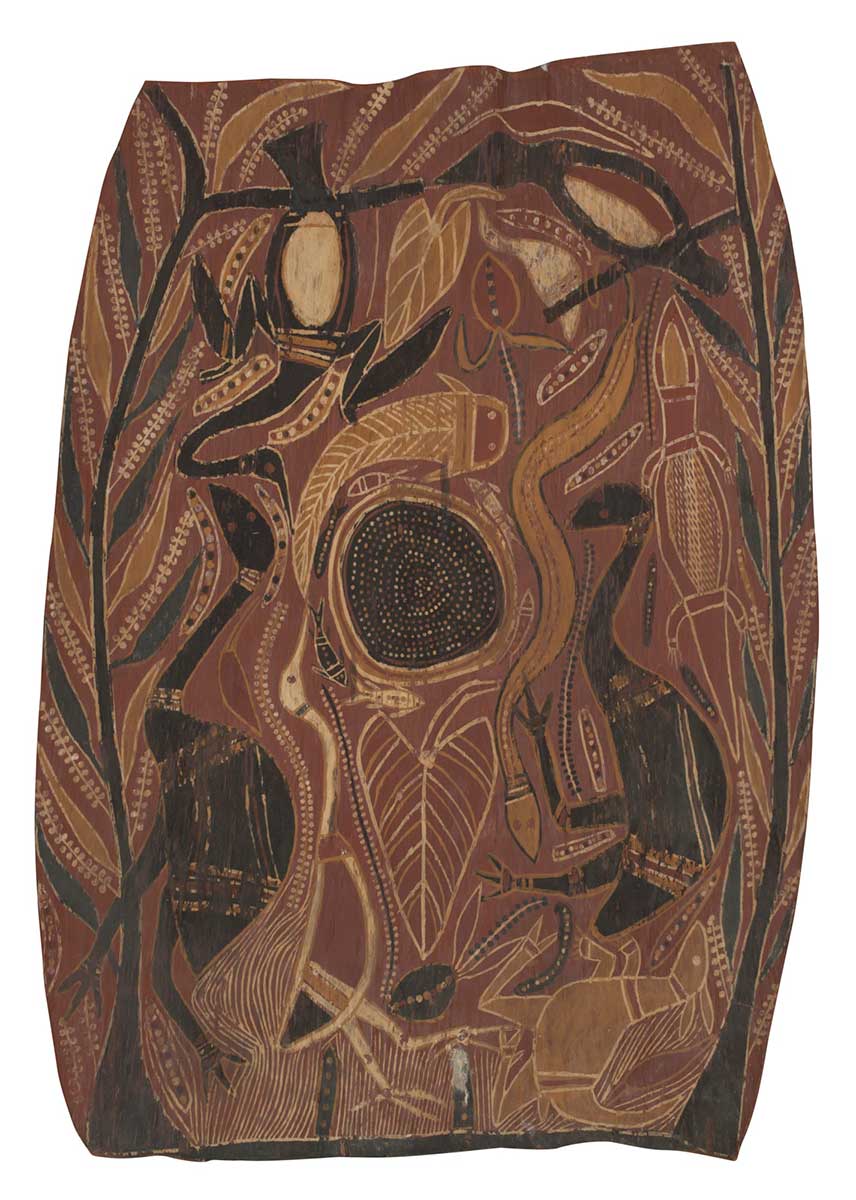

The Djan’kawu arrived with the dawn and are linked to Banumbirr the Morning Star, which is symbolised by the yam plant. In Bartji (Jungle Yams), Jack Wunuwun, a master of the visual pun, has drawn the tubers of the plant in profile to suggest the human body with arms outstretched, as if performing in ceremony. He has transformed his subject from one realm to another, from the natural world to the ancestral. The vines of the yam plant symbolise the feathered string that ancestral beings attach to Banumbirr the Morning Star on its daily pre-dawn journey heralding a new day.

David Malangi used to joke that he was the most popular painter in Australia. His image of the burial of Gurrmirriŋu the Ancestral Hunter was reproduced on the $1 note when decimal currency was introduced to Australia in 1966. As Malangi used to say, most Australians carried his painting in their wallets.

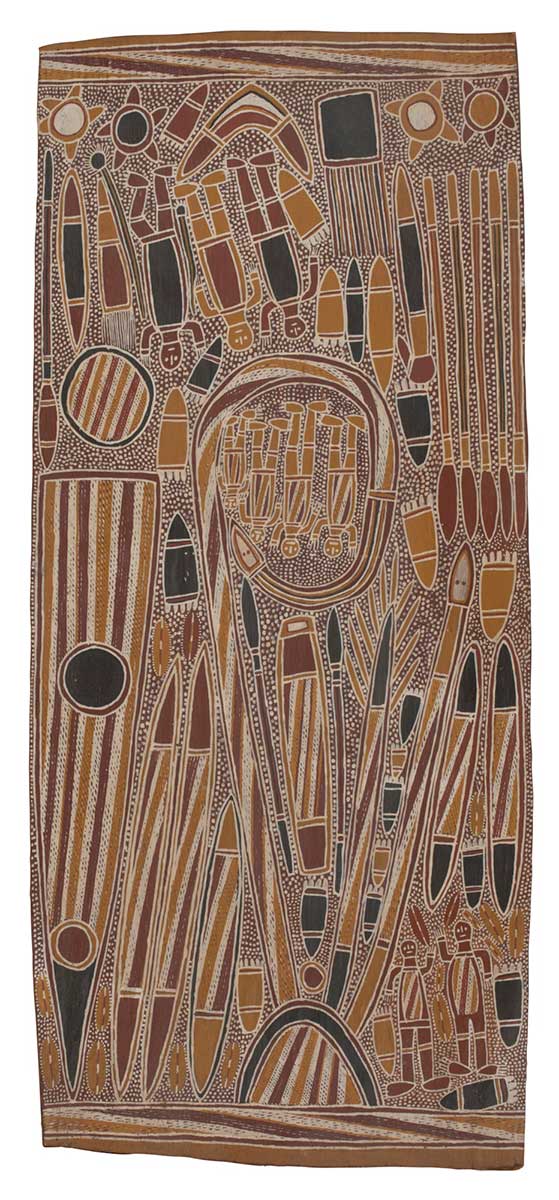

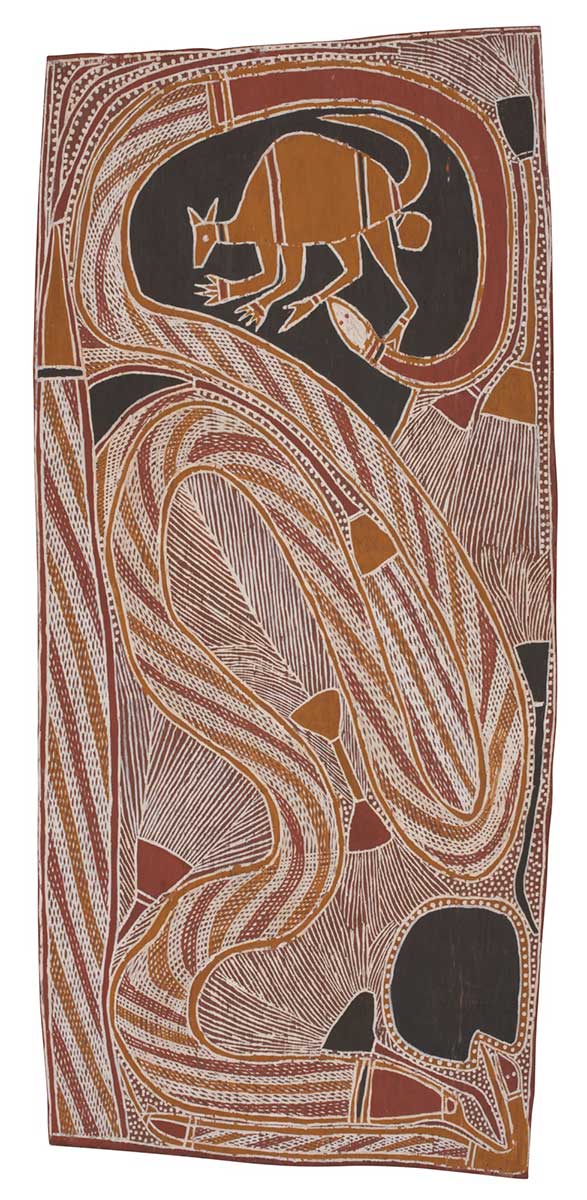

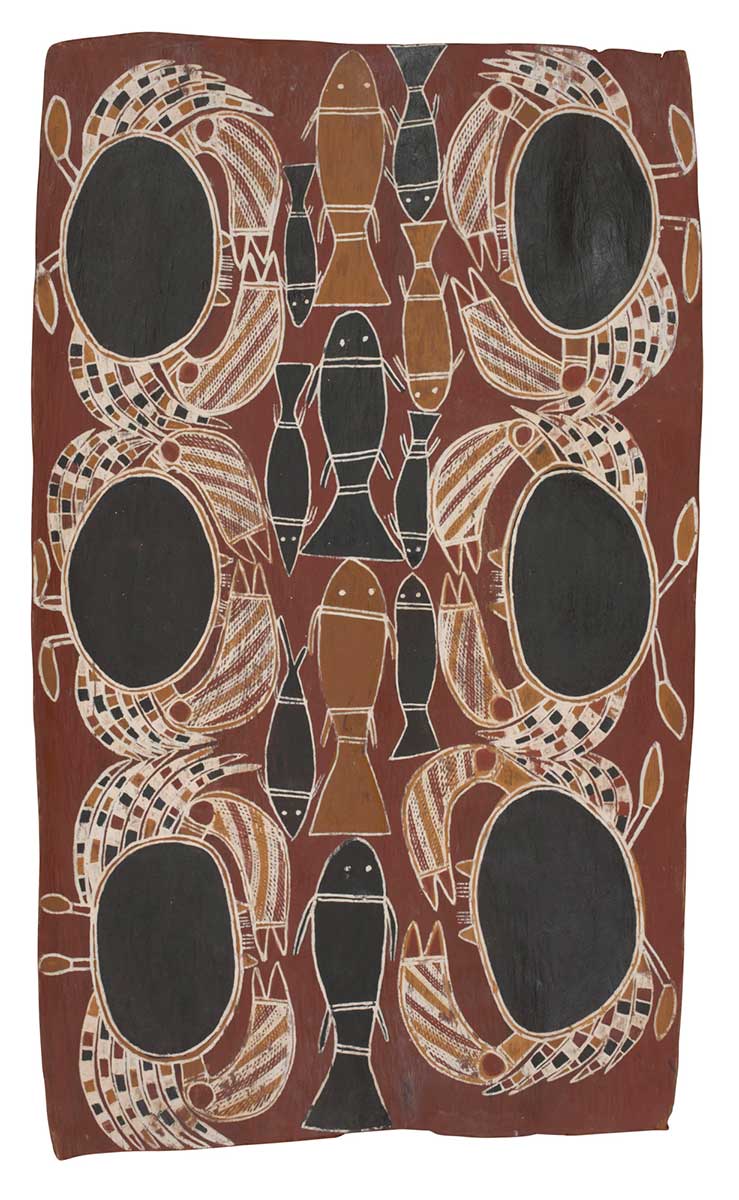

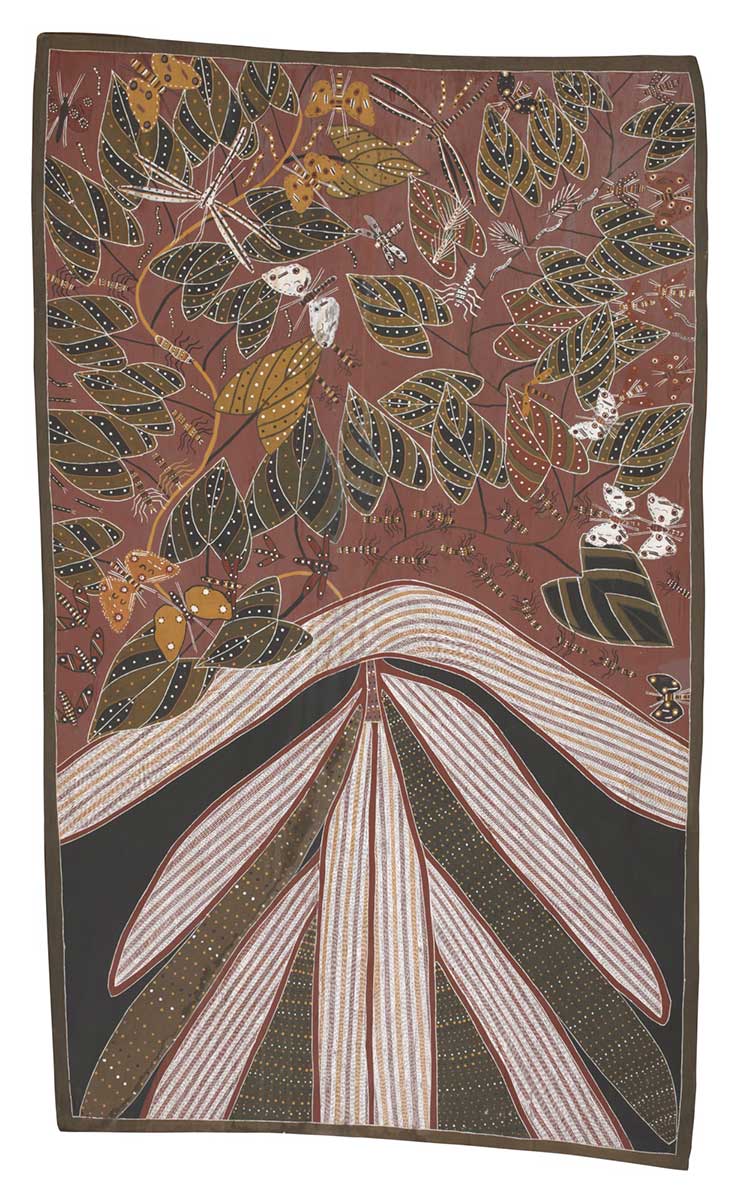

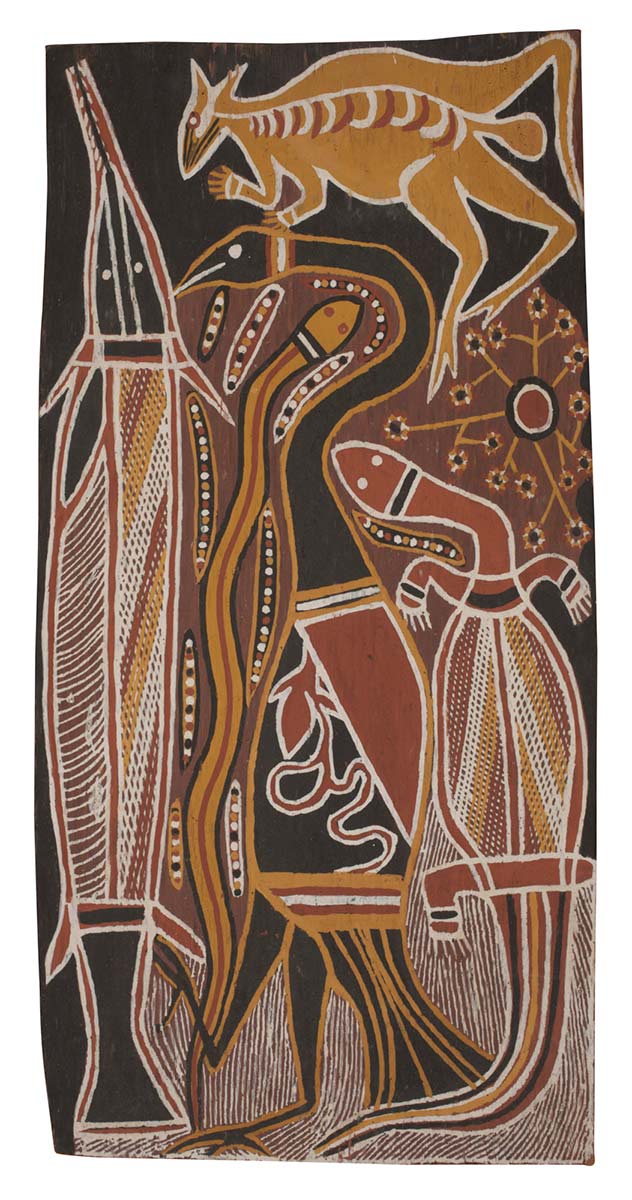

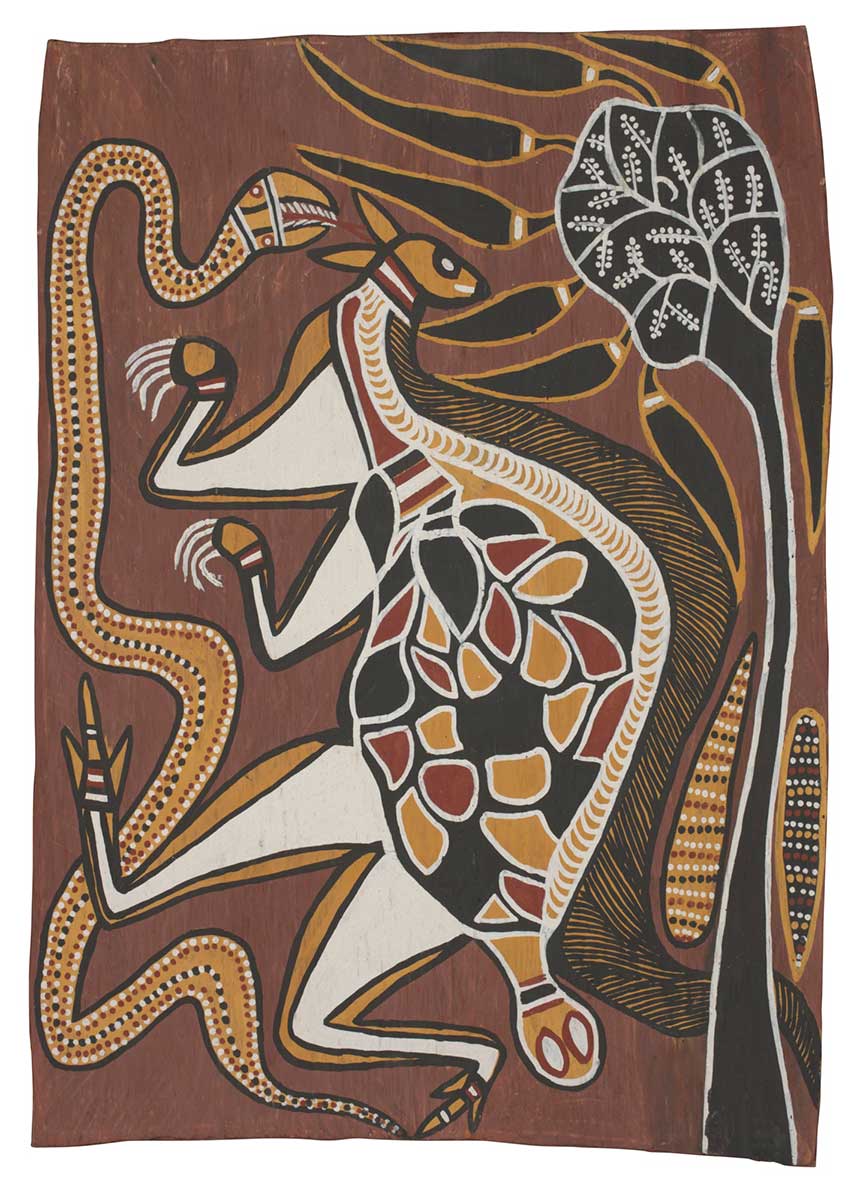

Malangi paintings show aspects of the story of Gurrmirriŋu, who died from the bite of a venomous snake. The Manharrŋu clan performed the first burial ceremony for him while a mortuary feast was prepared beneath a wurrumbuku (white berry tree). Gurrmirriŋu’s body was painted with the Manharrŋu clan design. Waterhole Life shows totemic animals surrounding the clan waterhole, which contains the souls of clan members. The central positioning of the waterhole reflects its significance to a person’s identity. When a clan member dies, a diver duck descends into the waterhole and plucks their soul from the circle of life.

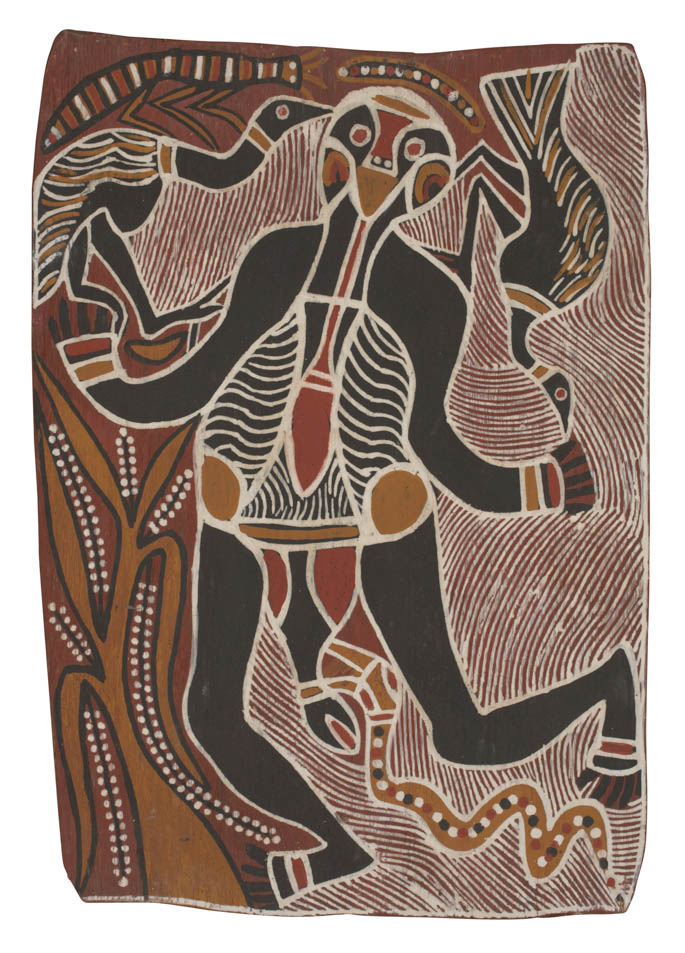

Malangi had a unique way of drawing dangerous spirit figures. He often incorporated elements of X-ray drawing to show the skeleton and internal organs of his subjects. X-ray is normally associated with painting in western Arnhem Land. The Dead Gurrmirriŋu depicts the hunter’s body in a state of decay as birds eat at his flesh in a symbolic act of purification.

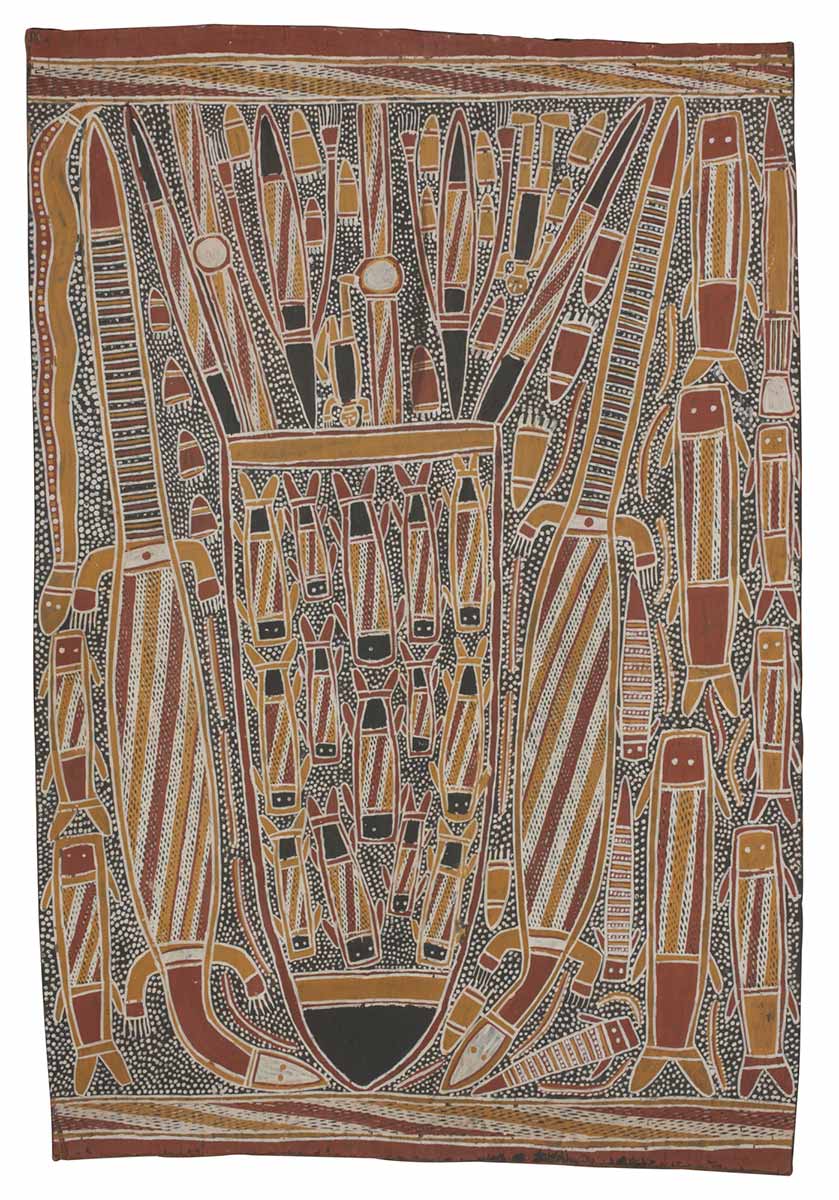

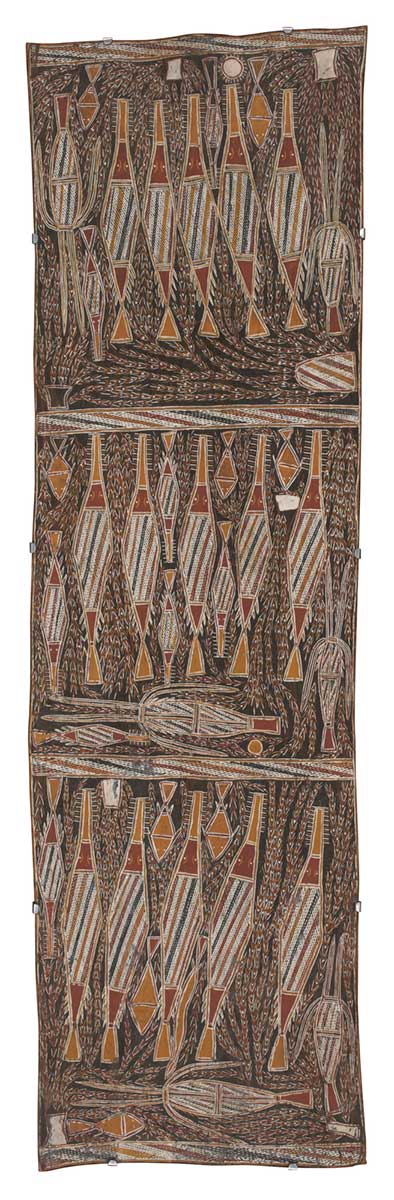

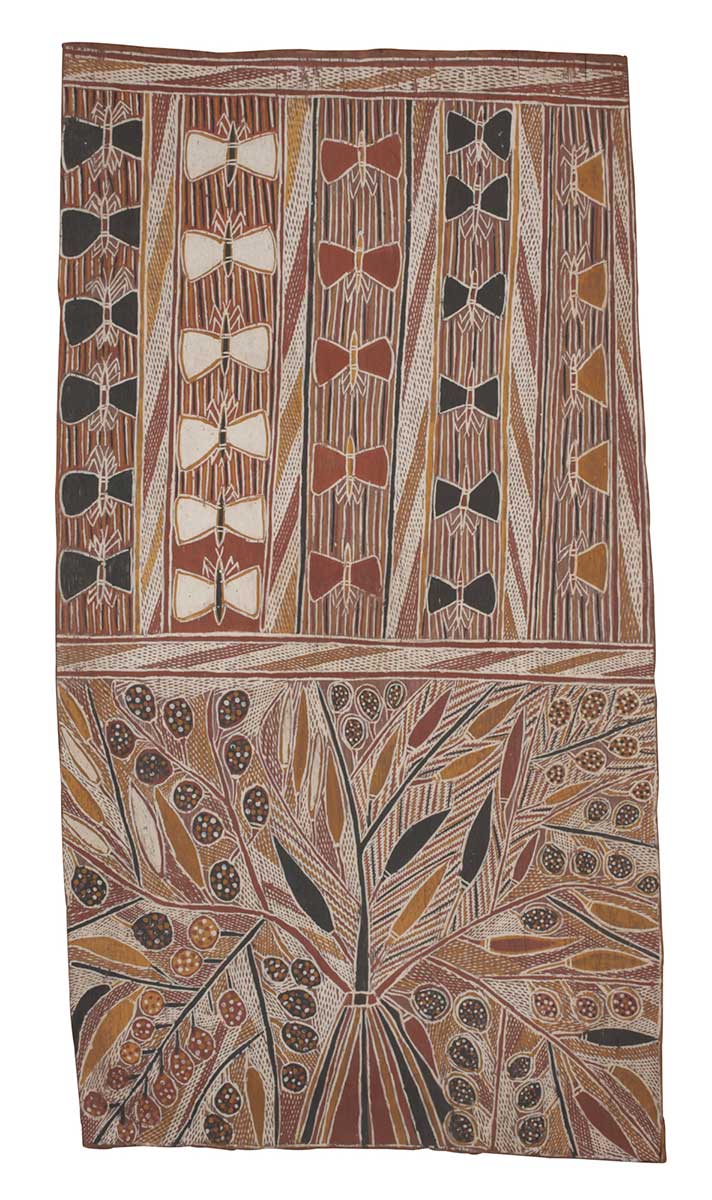

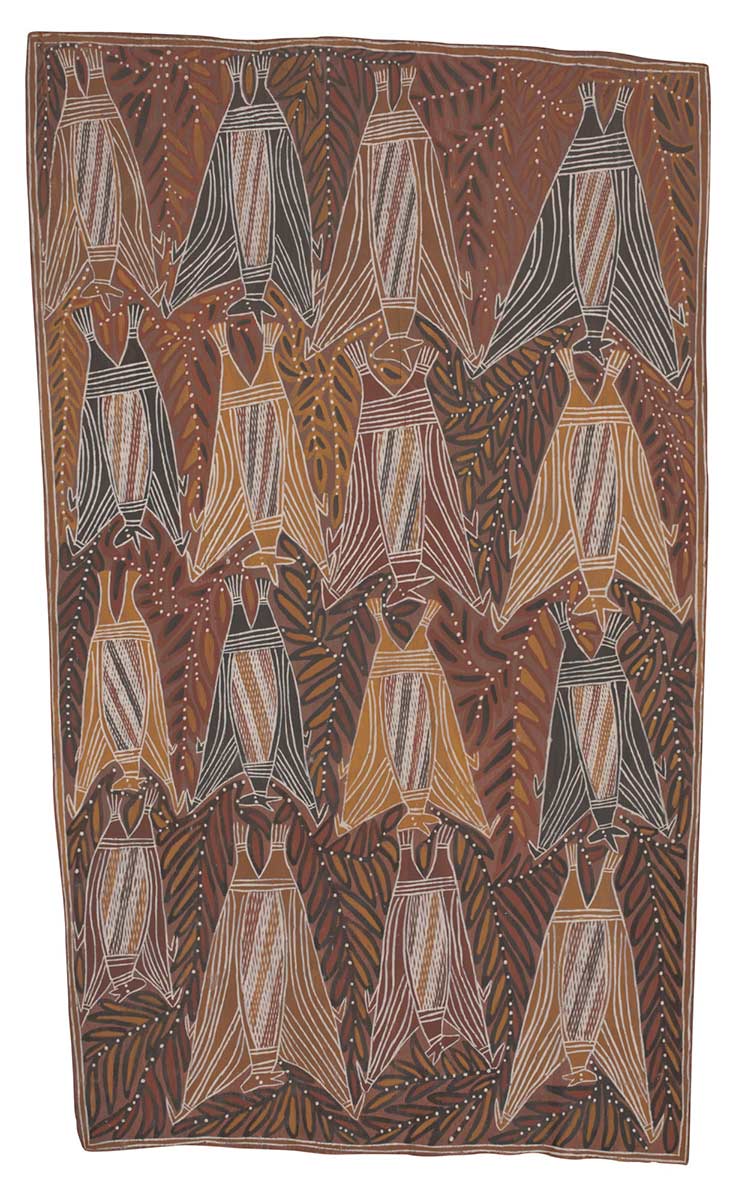

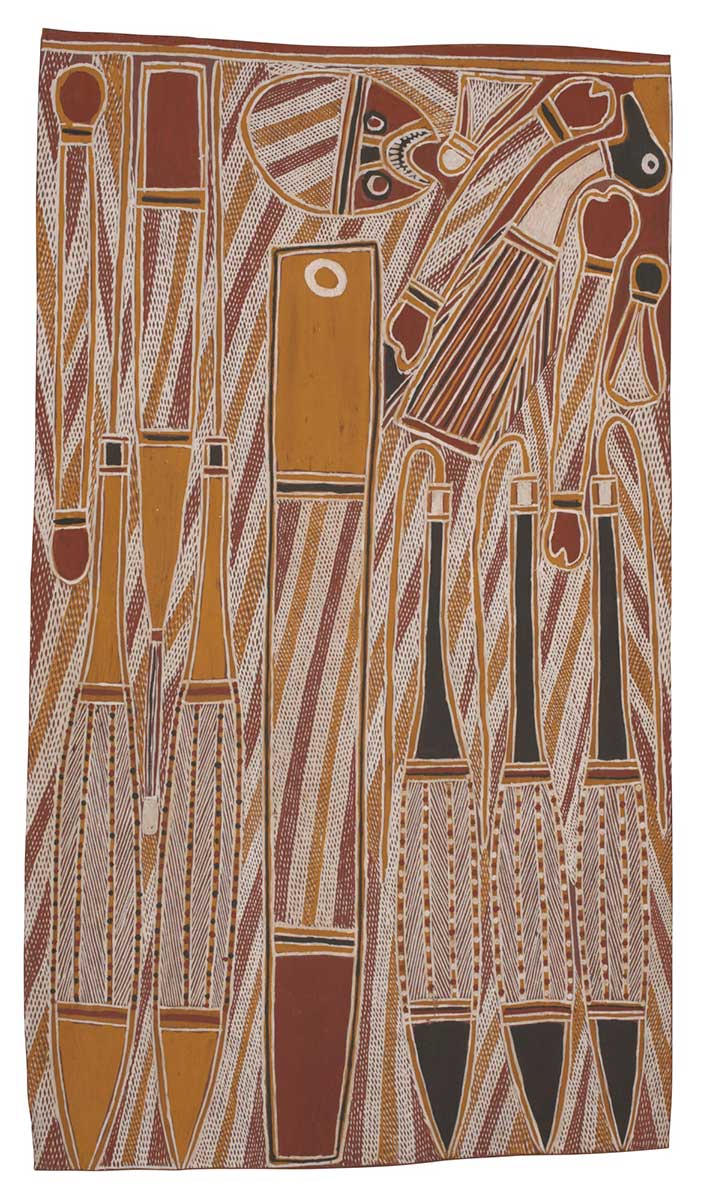

George Milpurrurru and his kinsman John Bulunbulun’s traditional lands lie in and around the Arafura Wetlands. It is a landscape teeming with wildlife and lush with vegetation. Ancestral flying foxes (fruit bats) are the custodians of Ŋlyindi, a major sacred site in the region. Milpurrurru has depicted the creatures in organised rows, and drawn them to resemble ceremonial objects such as the staffs in Raŋga (Ritual Objects) for the Yirritja Flying Fox Dance. The regularity of these compositions suggests the rhythms of ceremonial dance.

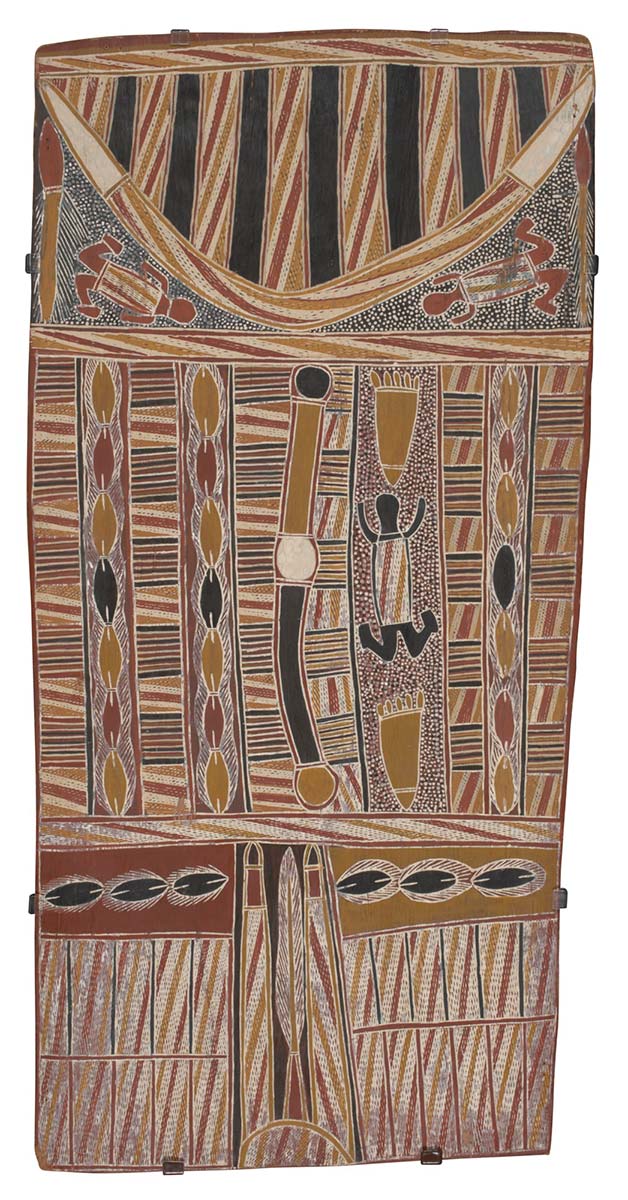

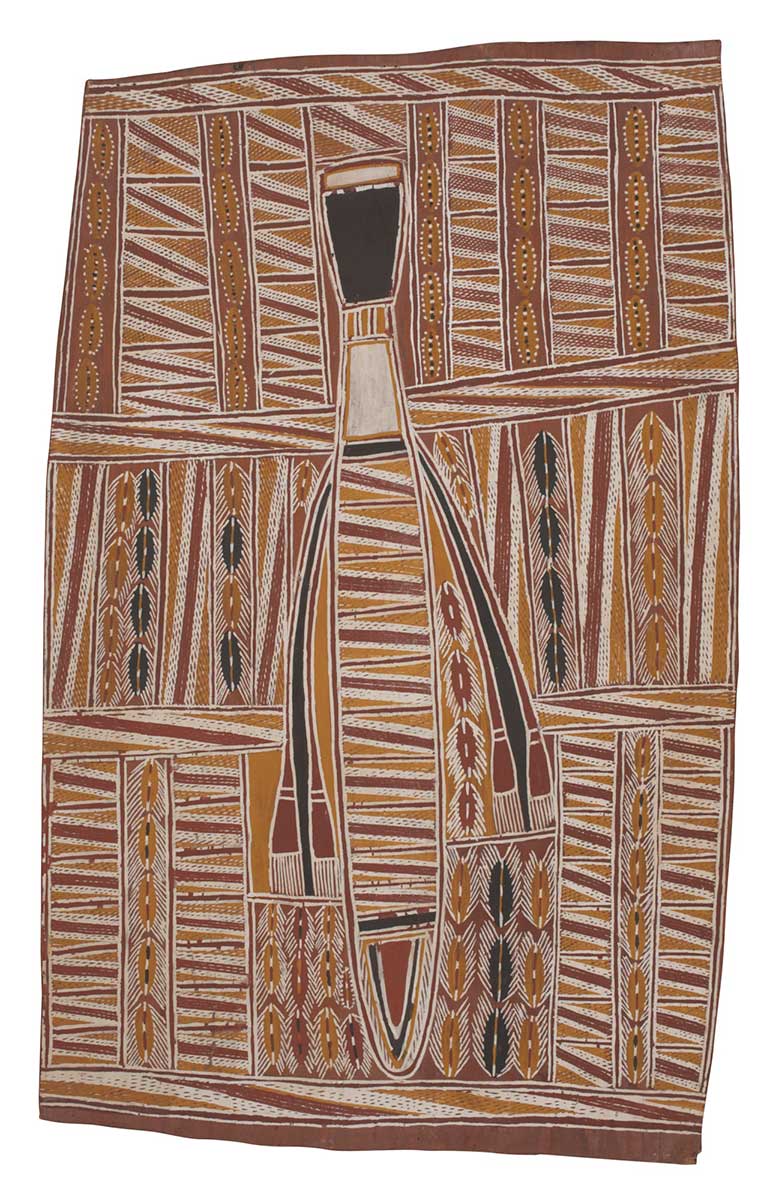

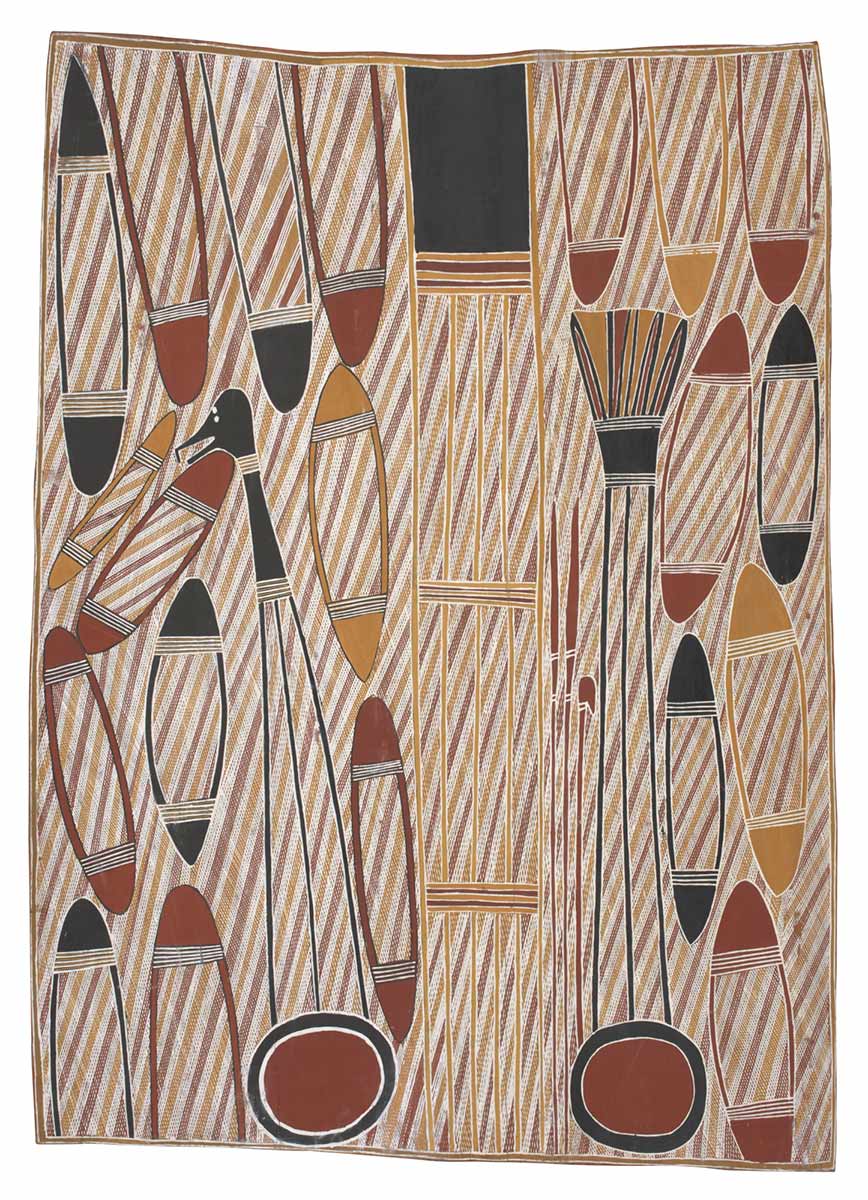

Shown in the centre of Ganalbiŋu Funerary Rites is a vertical log-coffin to house the bones of a deceased clan member. The bone burial ceremony marks the safe arrival of the soul to the ancestral realm and the end of the mourning period. All the elements in the painting – the coffin, the ritual objects and the magpie goose and waterlily totems – are decorated in the same clan pattern as the background, allowing them to take on an aura of invisibility to evoke the presence of sacred ancestral forces within the ceremony – and within the painting itself. Binyinyuwuy’s painting is another version of the same ceremony.

Milpurrurru’s Galawu (Stringybark House) depicts two types of bark hut: the curved shelters built on the ground in the dry season, and the platform shelter on stilts for the wet season. ‘Galawu’ also describes the large sheets of bark used for painting.

Portraits of people, as the representation of their physical appearance and facial likenesses, are not part of the traditional Aboriginal artist’s repertoire. To Bininj and Yolŋu, a person’s identity – their kinship ties, totemic associations, clan group and connections to ancestors and country – is of much greater significance.

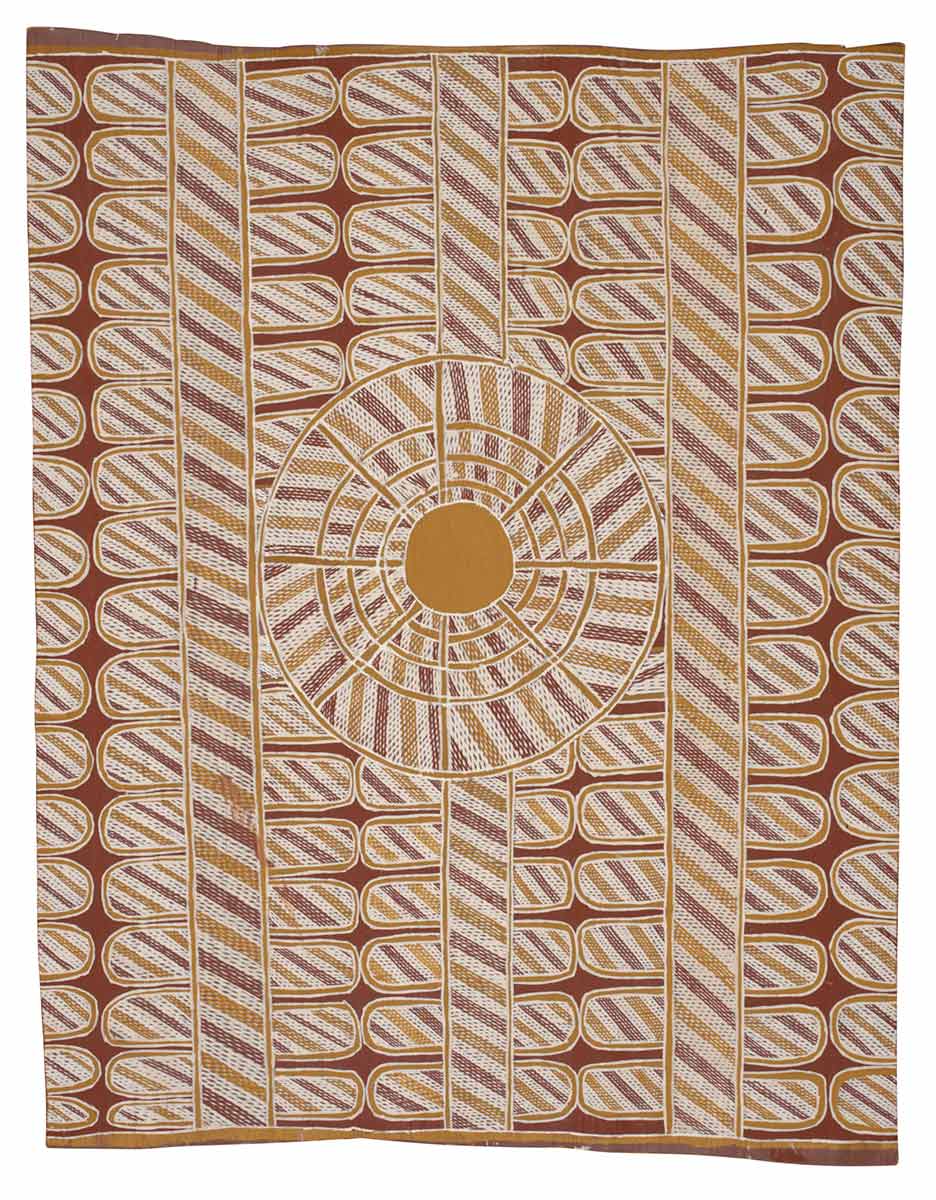

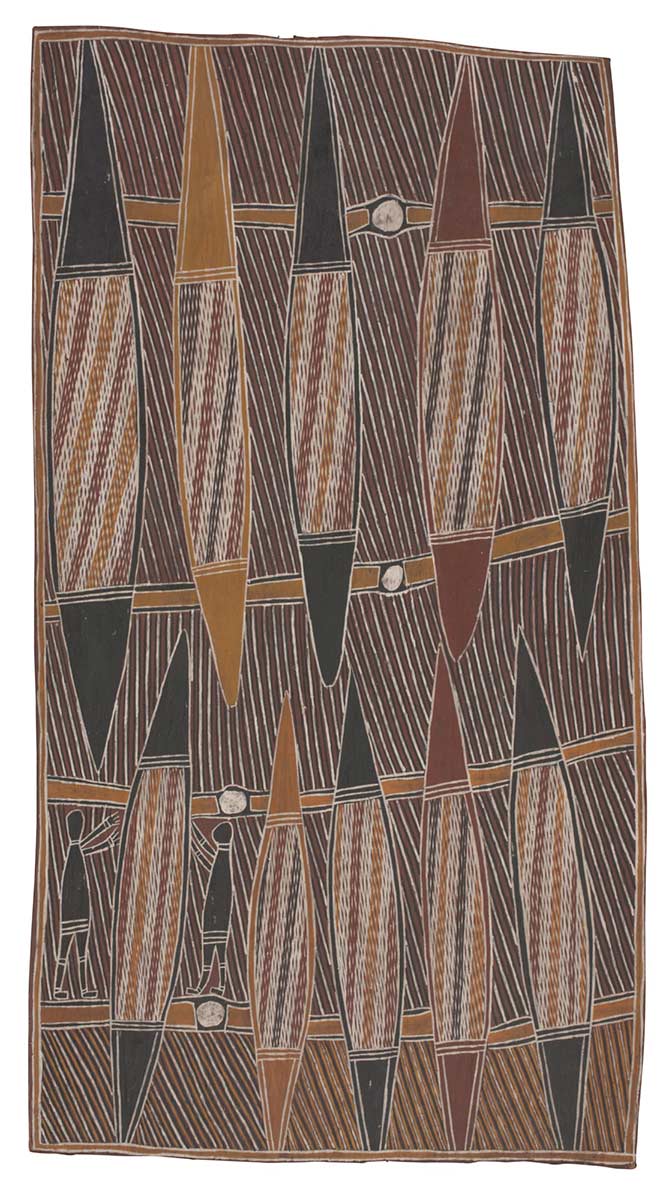

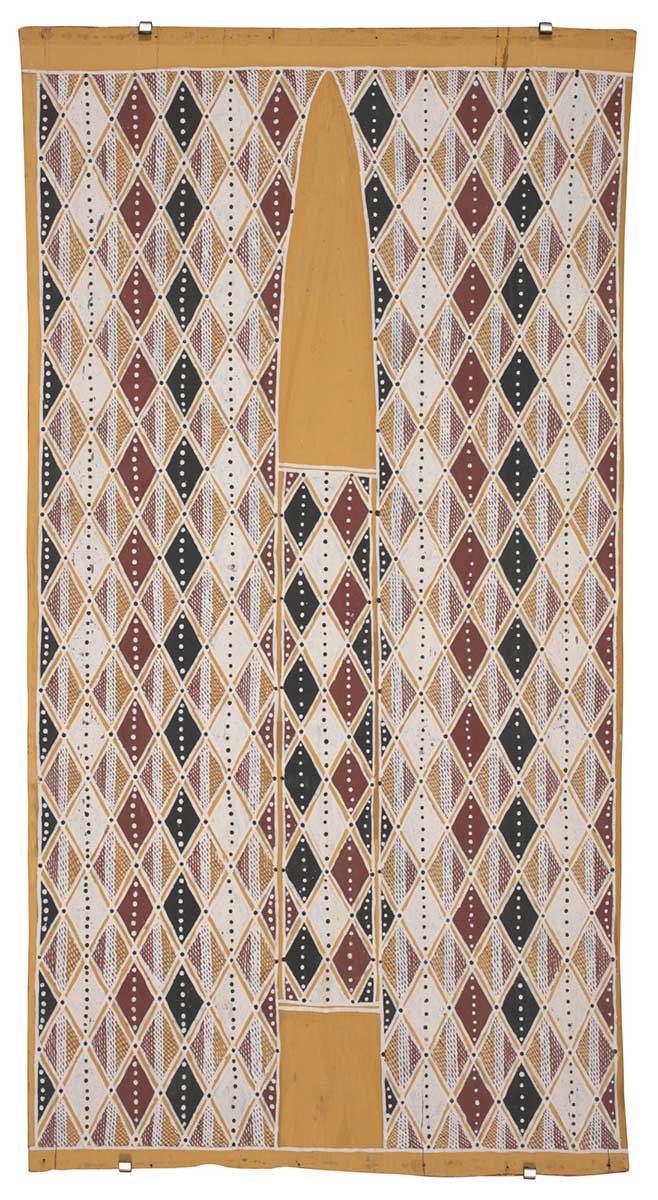

The two paintings here may be regarded as self-portraits of the artists Harry Makarrwala and Jimmy Wululu. Makarrwala belonged to the Wangurri clan. His clan design represents the patterns made by milka (mangrove worms) on a sacred log. The extensions at the top of the work mimic body painting arching over the shoulders.

Wululu belonged to the Daygurrgurr clan of the Gupapuyŋu group, and his primary totem was Niwuda (honey or sugarbag), associated with the Honey Ancestor Murayana at Djilwirri in central Arnhem Land. The diamond pattern shows the bees’ hive, with cells in various stages of development, within the trunk of the tree that appears in the centre of the painting.