Jenny Newell, National Museum of Australia, 27 March 2009

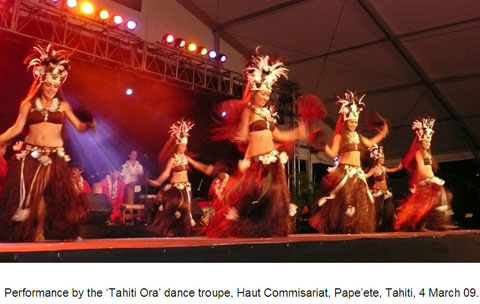

JENNY NEWELL: Hello everyone. I will begin with a short dance video from my recent trip to Tahiti. [Video plays]

Tahitian culture is really vibrant. It always has been. There is a wealth of Tahitian material in museums, some 11,000 objects across the world. These are the result of exchanges between islanders and Europeans since 1767. [View objects from Tahiti and Society Islands in the Cook-Forster collection] The range of objects stretches from the ceremonial and the martial to the everyday, reflecting deep changes over time as new materials and new ideas were brought in by outsiders. But all these things that entered museums - primarily in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries - have been largely sitting on storehouse shelves ever since. Most of the Tahitian objects in international museums have never been studied or published or visited, let alone exhibited. Few Tahitians know what is out there.

[Additional material inserted by presenter] Of course, there is only ever limited space to represent any one culture within a museum. However, some of the world’s cultures seem to get routinely more case space than others. This is not because some cultures are less interesting or relevant than others - it is largely, I would argue, because habits of thought within Western museums about scales of significance: valuing what are seen as the ‘Great Civilizations’ of the world; Egypt, Greece and Rome, China and Japan, the Incas or the mainstream cultures that surrounds the museum. With the notable exception of this museum, national stories are often told with limited reference to the impact of relationships to other nations. There is a circularity that occurs when generations of museum educators and marketers aim to tell stories that the public will recognise, a recognition that is shaped by what has been represented previously. Cultures of the Pacific have routinely been overlooked in public forums from the early-nineteenth century to today. One of the few ways that Pacific curators can guarantee a display of Pacific material is to stage an exhibition about Captain Cook. Small wonder that Pacific Islanders struggle to have their voices heard on any international stage.

Walking into the Pacific storeroom of any of the world’s major museums tends to be an exciting, but slightly unnerving experience. While the objects can be seen as a resource celebrating the creativity and diversity of the region, many of them are there as a result of processes of missionisation and colonisation. [end of additional material] In the case of Tahiti, a place that interests me particularly, and a place that has an unusually long history of being ‘collected’ by the West, islanders are now trying to revive traditions and practices forcibly banned 150 years ago by the Christian Church and by the French colonial government. There is an increasing moral imperative for museums to open up the cultural patrimony that they hold.

I have recently surveyed world museums to see what is held from Tahiti and the other Society Islands and see what those institutions have done with the objects. For the most part museums with these collections - from St Petersburg to St Louis, from Osaka to Otago - have rarely displayed them. On the rare occasions that some Tahitian objects are shown, this is typically without context, without a sense of the people who created the objects, or the changes they have made, or the world that they live in now.

Museums and art galleries often present Tahitians and other Pacific Islanders as if they are perpetually stuck in the eighteenth century.

Tahiti once occupied a dynamic place at the centre of European debates about the nature of human society. Descriptions of the islanders’ rituals and sexual practices were brought back by voyagers, and visits from the islanders themselves, captured the public imagination with a frisson that meant the islanders were talked about, written about and their works collected, traded and viewed at exhibitions throughout the Enlightenment era.

For Europe, Tahiti was the first, and quintessential, exotic Pacific island. By the mid-nineteenth century, once missionaries, colonists and traders had rushed to the islands, Westerners found the uniquely romantic appeal of the island had leached away. It fell out of the public view. It is unfortunate that now Western conceptions of the island have been shaped not by presentations of the islanders’ rich culture but by books, exhibitions and movies about famous Europeans who have stopped there. Tahiti is seen as a place of palm trees with some vague association with Gauguin, Captain Cook and Bligh’s mutiny (or was it Mel Gibson’s mutiny?).

This paper is an overview of how one culture has been collected and represented by the west. My key point is that absences in museum cases have political implications.

I am hoping to convince you that this island in the middle of the Pacific can be relevant to our own thinking about the responsibilities of museums and the implications of how we use or ignore the collections in our care.

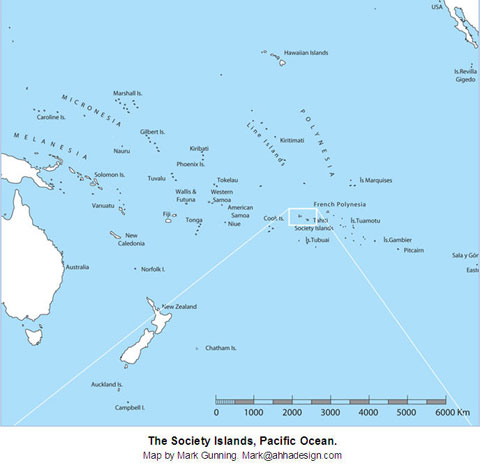

I will give you a quick overview of the phases of collecting and exhibiting Tahiti [shows map] before suggesting ways forward for reconnecting collections to communities and reinvigorating them for a broader audience. As Ranginui Walker, a Maori anthropologist, has said:

If taonga (cultural treasures) are not to be reduced to mere ‘museum pieces’ then ways and means must be devised of relating them to the living.

This is something that the curators at the National Museum of Australia know well and already address in every stage of their curation of exhibitions. Here and across Australia, however, there is no general public recognition of what political, economic or environmental issues are currently facing many Pacific Islanders, despite the entwined stories of our two regions, or the number of islanders living here, or the long-term impact of Australian policy on the islands. Many people would have trouble identifying where the islands are, let alone what goes on there. Museums could be broadening these horizons.

A brief historical overview:

Since Europeans started visiting Tahiti in 1767, the mutual collecting of each others’ material culture has been enthusiastic. When British, French and Spanish voyagers visited the island, the Indigenous people of the Society Islands, the Maohi, were keen to trade away their own goods and their fresh food and the company of women to secure the Europeans’ exotic and useful glassware, metal tools, woven cloth and scissors. Collecting is not a practice exclusive to Europeans: while islanders did use some of these commodities, they obtained others to keep them for their own sake; they were being ‘collected’.

The islanders could easily trade away everyday tools such as adzes that were being replaced by European versions made in iron, and commoners could re-make fish hooks and pounders. It is these everyday tools that are most common in museum collections now. The more elite items belonging to Tahitian chiefs and priests were given or traded away more carefully and only to those on a ship who could make good on the exchange - the captain and the officers. Museum collections reflect these economies. Honolulu’s Bishop Museum, for instance, of its 544 objects from the Society Islands has 181 adze blades, 84 pounders, 31 fishing hooks and only four to’o, the sacred figures for containing a god.

In the first voyaging phase of European collecting, seamen brought back objects as souvenirs, gifts and for sale. There were enthusiastic audiences for objects brought back by Captain Cook at the Leverian Museum in London and at the British Museum. While the public was genuinely interested in finding out about the new peoples being discovered, these larger museums had different agendas and displayed extraordinary, completely unfamiliar objects, like the mourner’s costume, without any explanation of what they were - just a label proclaiming their connection to Cook or Joseph Banks.

Each phase of representing the Pacific has had impacts on how the public understand and interact with the islands.

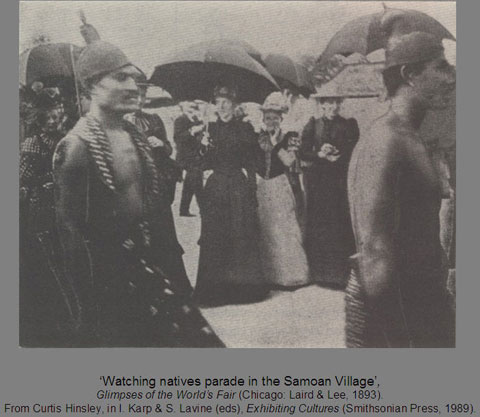

The next face of representing Tahiti trumpeted the civilised progress being made on the island. From the mid-nineteenth century sacred figures were confiscated or given up by chiefs, such as Pomare II, when they finally converted (often for political reasons). They sent ‘idols’ back to London to be shown at the Missionary Museum as trophies of success and to garner more support for the cause. Then, colonial exhibitions from the 1850s showcased not just the industry and progress of each nation but their expanding colonies. They displayed plantation commodities and pointed out that islanders now used ‘our’ western ceramic and glass.

The Paris Exposition of 1889, inspired by the pseudo-anthropological shows of Indigenous peoples being toured around Europe, installed mocked-up villages, including a Tahitian village, with islanders going about their supposed everyday life for the education and entertainment of visitors. Villages were soon included in the American world fairs (providing rather unnerving viewing for some, by the looks of things). The expositions inspired a broader range of people to continue the pursuit of looking at other cultures in ethnographic displays. Museums gained broader audiences.

Meanwhile, in Tahiti, traditional practices - carving for rituals or for chiefs, tattooing, or travelling between islands - had been forced to a halt by the church and colonial government in favour of more controllable and profitable pursuits. Many parts of material culture stopped being produced. The appeal of the Islands was later revived in the visual media of tourism. Islanders responded to the new type of collectors with suitable carvings and models, such as model canoes.

From the late nineteenth century, exhibition representations followed the new hierarchical ethnography of race. Polynesian culture was shown in the 1940s as an essentialised, primitive art. By mid-century, primitivism started to give way under the influence of cultural anthropology and curators were more likely to approach their collections as windows into cultures.

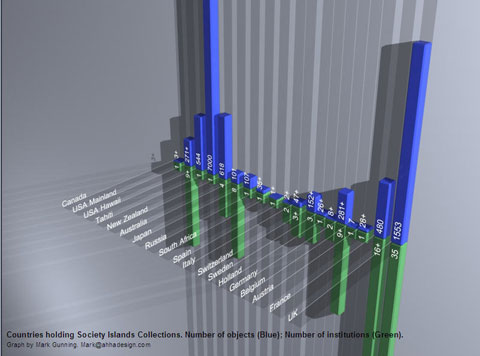

A few museums are collecting contemporary Tahitian arts, not just the British Museum but also Te Papa, Queensland Art Gallery and the Bourke museum in Washington. During my survey of material from Tahiti and the other Society Islands (Mo’orea, Raiatea, Huahine, Borabora and Maupiti), I found at least 11,270 objects from the Society Islands in at least 101 institutions around the world. There are likely more; this is a work in progress.

I was surprised and heartened to discover that most objects are in the Pacific itself. Of the 11,000 world total, 7,000 are in Tahiti itself at the Musée de Tahiti et des Îles. There are many objects in museums in the neighbouring settler communities of Hawaii (544) and New Zealand (7000). The other big presence on the graph is the UK (1553). The British have always been consummate collectors and of all visitors they have had the longest association with the islands.

The Musée de Tahiti et des Îles has a very large collection. This is partly because the French colonists established the museum very early for the Pacific, in 1917. But it can also be argued that Tahitians already had a comparable tradition of keeping treasured objects in a Fare ia Manaha - a sacred treasure house. Fare ia Manaha is now part of the museum’s name, recognising that earlier connection. The Musée de Tahiti has had support and donations of objects from not just the resident French, Chinese and other ethnic groups but also from Indigenous Tahitians. Today, some Tahitians will leave potent, old spirit figures at the musée to get them safely away from the home.

Students at the local art and crafts college draw on the Musée’s objects as models, and all school children go through there at least once. While some of the old clichés do crop up, perhaps for the benefit of tourists [shows poster of Gauguin exhibition], but the musée has had an effective contemporary collecting program and has been successful at securing the return of a range of important objects from overseas by donation and auction purchases.

Given that Australia’s closest connection to Tahiti was through Sydney traders who were gathering pork and other commodities rather than artefacts, it is not surprising that there are apparently just over 100 Tahitian objects here in Australia, and the majority of these at the Australian Museum in Sydney where the strongest trade connections were.

The National Museum of Australia does have a good Pacific collection, and it is one that delineates its colonial connections particularly clearly. The collection includes 5000 objects from Australia’s former colony, Papua New Guinea, while it has only a single Tahitian tapa beater.

While large museums have online catalogues - the British Museum, Quai Branly, Smithsonian and Te Papa Tongarewa - it is otherwise hard to find records of worldwide collections electronically or in print. I was able to trace many of them only by emailing curators directly and hoping that they would find time to investigate their collections for me. Sometimes this was only possible because I had their business card. It would have been very hard for someone in the islands without museum connections - and without a reliable Internet connection - to have carried out the same research.

Museums are generally daunting places for those not part of the culture that created them. Most museums are implicitly authoritarian - something which is embodied in their very structure [shows some classical facades] - and any islanders wishing to visit collections in these institutions need to get past this kind of frontage. Finding or gaining access to their cultural heritage is the next challenge. When this kind of visit does happen, as anyone working in museums knows, it is immensely rewarding for both the institution and the visitor. The flow of information and inspiration is two-way.

Collaborations between source communities and museums provide the best opportunity for making islanders feel at home in the museum. And as Howard [Morphy] pointed out this morning, it is the best way forward for creating exhibitions that convey issues that matter and of relating cultural treasures to the living.

Projects such as the Pasifika Styles exhibition and art program in Cambridge involved artists from the outset and included the artists’ voices, both literally and in audio recordings, at every stage of the process. Exhibitions such as Stephen Hooper’s Polynesian Encounters, and the British Museum’s Power and Taboo in 2006 both presented primarily historic material but brought their subject to life through imagery, vibrant performances, ceremonies, conferences, artists in residence and talks provided by Polynesian communities.

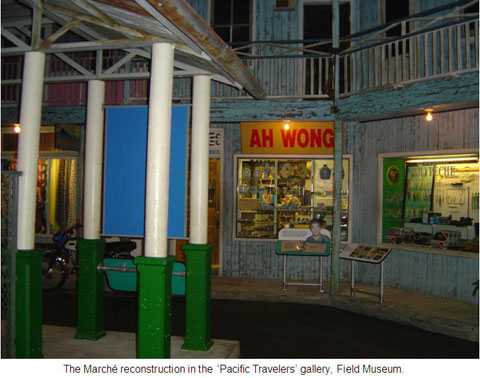

As Charlotte [Smith] showed us this morning, reconstructions can be incredibly effective. The only dedicated Tahitian exhibition outside of Tahiti is a reconstruction at the Field Museum in Chicago. As part of their Pacific travelers exhibition they have reconstructed Pape’ete’s market in their Pacific gallery. These are some pictures of the market that I took earlier this month [shows images]. Based on detailed research, one side of the marché building has been recreated full size, with the road around it, lined with its multicultural food shops and videos of discussions with Pape’ete inhabitants. It allows the visitor, for once, to gather a comprehensive sense of life in Tahiti as it is lived now. The mélange of cultures, the urban face of things, the global commodities and the continuation of old ways of doing some things like preparing food - these things are all apparent simply by walking through the reconstruction. Dioramas and reconstructions are of course very resource-intensive and highly mediated interpretations. But for an audience who knows little, if anything of Tahiti, it will usually take more than a bland presentation of a pounder on a pedestal to make a difference.

In conclusion, ethnographic museums around the world are now generally trying to become more accessible to their local audiences and source communities. In addition to increasing collaborations, museums could usefully improve access through loans programs and more online databases. Commissions and purchases from practitioners are a way to invigorate collections in which the selection of material is guided by local values rather than just the curators.

It is unlikely that Australian museums will make changes any time soon to their minimal coverage of Pacific cultures, but exhibitions that open up Pacific cultures to a broader audience, such as Vaka Moana coming to the National Museum of Australia from June to October this year and the proposed exhibition ‘Luk Luk Gen’, on contemporary Papua New Guinea art, are ideal vehicles.

Museums around the world hold the legacy of their Enlightenment and colonial pasts, the material results of their engagements with islanders. They hold a great potential for providing ways for people around the world to recognise and connect to the islands, and for islanders to connect to their heritage in ways that are becoming increasingly important. Thank you.

QUESTION: Kylie Message from the ANU. Thanks, Jenny, that was really fascinating. I am interested to know more about the collections that are held in the Pacific region. In particular I am interested to know when the collections were acquired and whether there has been a vast increase in contemporary collecting in the last couple of decades that has accounted for the majority of collections being held in this region.

JENNY NEWELL: Because they are settler communities, collections did start quite early in both Hawaii, New Zealand as well as in Tahiti. Those collections did begin from about the nineteenth century when there were large European populations in those places with their culture of collecting that came along with them. But because the museums in Hawaii, Tahiti and New Zealand are really connected to what is happening locally, their contemporary collecting programs are really active and very positive. They have a lot of support from people from Tahiti who are living in each of those places so they are getting really interesting material all the time. Although they do have good strong collections historically, they have also got good contemporary collections too.

GUY HANSEN: Thanks very much, Jenny.

Disclaimer and copyright notice

This is an edited transcript typed from an audio recording.

The National Museum of Australia cannot guarantee its complete accuracy. Some older pages on the Museum website contain images and terms now considered outdated and inappropriate. They are a reflection of the time when the material was created and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Museum.

© National Museum of Australia 2007–26. This transcript is copyright and is intended for your general use and information. You may download, display, print and reproduce it in unaltered form only for your personal, non-commercial use or for use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) all other rights are reserved.

Date published: 01 January 2018