Solving the mystery of the disc

To set a telescope to point at a specific star, an astronomer needs to know a star’s declination and its hour angle. Declination is listed in star catalogues, but the hour angle must be calculated using the star’s right ascension (also listed) and local sidereal time. Sidereal time is determined by the Earth’s movement relative to ‘fixed’ stars, while solar time derives from the Earth’s rotation relative to the sun. They differ by about four minutes per day.

Until the 1880s, each time an astronomer wanted to set his telescope to view a particular star, he had to calculate the star’s hour angle. Then manufacturer Thomas Grubb developed a mechanism enabling local sidereal time to be set on a telescope. This meant that an astronomer could direct his telescope to a star by simply setting its declination and right ascension. With Grubb’s innovation, the telescope could be moved to view several stars during a night’s observing without having to stop each time to determine each star’s hour angle.

Zoom

Conservator David Hallam and engineers Col Ogilvie and Hermann Wehner loosen the sidereal time setting circle from its sleeve.

When the Museum acquired Macdonnell’s telescope, the conservation team was perplexed by a brass disc with silver degree scales positioned at the base of the polar axis mechanism, as it appeared to serve no purpose. Eventually, thanks to research by astronomer Wayne Orchiston, the team discovered that Macdonnell’s telescope was one of the first models fitted with Grubb’s new mechanism. The brass disc was the sidereal time setting circle. It failed to work properly because it had become stuck fast to the surrounding sleeve. Once cleaned and re‑oiled, it was returned to working order.

Zoom

Conservator David Hallam and engineers Col Ogilvie and Hermann Wehner loosen the sidereal time setting circle from its sleeve.

When the Museum acquired Macdonnell’s telescope, the conservation team was perplexed by a brass disc with silver degree scales positioned at the base of the polar axis mechanism, as it appeared to serve no purpose. Eventually, thanks to research by astronomer Wayne Orchiston, the team discovered that Macdonnell’s telescope was one of the first models fitted with Grubb’s new mechanism. The brass disc was the sidereal time setting circle. It failed to work properly because it had become stuck fast to the surrounding sleeve. Once cleaned and re‑oiled, it was returned to working order.

Zoom

The sidereal time setting circle on the polar axis

Zoom

The sidereal time setting circle on the polar axis

Zoom

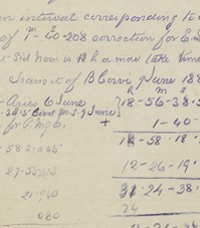

Diary notes showing WJ Macdonnell’s calculation of local time at Port Macquarie using sidereal time, and coordinates for the bank observatory

Zoom

Diary notes showing WJ Macdonnell’s calculation of local time at Port Macquarie using sidereal time, and coordinates for the bank observatory

Watch

An animation showing sidereal time

Watch

An animation showing sidereal time